Step 1: Start

advertisement

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

As the culmination of a four-year competitive process, NIST (the National Institute of

Standards and Technology) has selected the AES (Advanced Encryption Standard), the successor

to the venerable DES (Data Encryption Standard). The competition was an open one, with

public participation and comment solicited at each step of the process. The AES, formerly

known as Rijndael, was chosen from a field of five finalists.

AES is suitable for any application that requires strong encryption technology. This new

encryption standard may replace the previously used triple-DES where the superior efficiency of

Rijndael algorithm can be used to gain much increased data throughput for less logic real–estate.

Typical applications might include secure communications, program content protection for

digital media applications, storage area, networks, VPN, secure VoIP, wireless LAN, electronic

banking etc..

AES is a 128-bit symmetric cryptographic algorithm. It is symmetric since same key is

used for encryption and decryption.The general Rijndael algorithm is a block cipher with

multiple options for its block and key size. The NIST approved AES is a subset of these options

with a fixed block size of 128-bits, but the key may be 128, 192 or 256-bits in length. This

means, that a basic AES engine is capable of encrypting plain text data in blocks of 128-bits

using any of the specified key sizes. Higher levels of security can be achieved by using bigger

key sizes.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

1

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

1.1 OUTLINE OF REPORT

This standard specifies the Rijndael algorithm, a symmetric block cipher that can process

data blocks of 128 bits, using cipher keys with lengths of 128, 192, and 256 bits. Rijndael was

designed to handle additional block sizes and key lengths; however they are not adopted in this

standard. Throughout the remainder of this standard, the algorithm specified herein will be

referred to as “The AES Algorithm.”

This specification includes the following sections:

Chapter 2. Evolution of Cryptography which briefs emergence of thoughts about

cryptography.

Chapter 3. Basics of Cryptography describing its principles.

Chapter 4. Security, Cryptography and Privacy depicts security and privacy aspects in

cryptography.

Chapter 5. Symmetric Key Cryptography describes the key standard used in AES.

Chapter 6. Implementation Tool – MatLab 7.6 briefs the details of project platform.

Chapter 7. AES with CBC algorithm which specifies idea of algorithm and steps involved in

it.

Chapter 8. High-level description of algorithm which explains the steps: SubBytes,

ShiftRows, MixColumns and AddRoundKey in detail.

Chapter 9. Flow diagram which describes flow of algorithm in both encryption and decryption.

Chapter 10. Block diagrams which describes Standard core encryption, decryption and

encryption/decryption standards in detail.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

2

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

Chapter 11. Inputs & Outputs given to and taken from the function.

Chapter 12. Key Expansion Algorithm & Flowchart which describes the key expansion

scheme used in AES

Chapter 13. Substiution Boxes which involves construction details of SBox, ISBox and

MixColumn matrices

Chapter 14. AES Encryption Procedure illustrates full encryption algorithm in a 4X4 matrix

Chapter 15. AES Decryption Procedure illustrates full decryption algorithm in a 4X4 matrix

Chapter 16. Algorithms illustrate full AES program in simple steps

Chapter 17. Block Cipher: Modes of Operation which describes and compares different block

modes

Chapter 18. Comparison with previous standard involves comparison between DES and AES.

Chapter 19. Attacks and Security which point outs the possible attacks on AES and the

security in AES against it

Chapter 20. Advantages of AES over other encryption techniques.

Chapter 21. Applications of AES Algorithm

Chapter 22. Limitations of the Algorithm

Chapter 23. Conclusion of the project

Chapter 24. References comprising of paper and web references.

Chapter 25. Appendix used for the implementation of project.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

3

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 2

EVOLUTION OF CRYPTOGRAPHY

The secure transport of messages was the concern of many early civilizations.

Since then, different methods have been developed to assure that only the sender and the

addressee would be able to read a message, while it would be illegible or without significant

meaning to a third party. Today, this practice continues with more fervor. Wireless, wired, and

optical communication networks are able to transport unimaginable amounts of data and thus

privacy of information and security of the network are of the utmost concern because a good part

of the transported information may be very sensitive and/or confidential. Confidentiality of

information has been particularly popularized with the explosive growth of the Internet, which

has touched most people’s lives. However, from the outset, the Internet was based on an open

network architecture with computer-based nodes and without network security, and thus was

vulnerable to attackers and hackers. The development of unbreakable cipher keys, cipher key

distribution, identification of malicious actors, source authentication, physical-link signature

identification, countermeasures, and so forth has been the major thrust of research efforts with

regard to cyber-security. This article focuses on cryptography, and is the first of a series of three

articles on cryptography and security in communications. Subsequent articles will cover wireless

and IP network security, as well as optical network security, quantum cryptography, and

quantum-key distribution processes specific to optical networks. In antiquity, sending a secret

message with a messenger through a hostile territory was as dangerous as it has been to date. The

messenger was subject to interception, and the message was subject to the integrity of the

messenger. As such, methods were developed to assure that the message would arrive at its

destination safe and untampered with. Although this article does not attempt to provide a

historical treatise on the subject, it is worth mentioning some sound and proven examples. The

ancient Mesopotamians would write a message in cuneiform script on a clay tablet that was

exposed to sun to dry. This tablet was then enclosed in a clay envelope, which was also dried.

Breaking the clay envelope to read the message would forfeit the message, particularly during

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

4

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

times of war, and thus the message was useless. Similarly, in ancient China, people would hide a

message in a cake (known as a moon cake) in order to get a message past the emperor’s guards;

today’s fortune cookie is an American concoction of the Chinese moon cake. Moreover, secret

messages have been found in hieroglyphs. Until the 1980s and prior to the advent of the Internet,

the communications circuit-switched network was in general inaccessible. Moreover, this

network was not challenged with virus attacks and the like; in fact, cyber-security is a modern

term that did not exist until the spread of the Internet several years ago. Thus, for many years,

network security had not been a priority and had been underemphasized or overlooked.

However, the circuit-switched network was not flexible and cost-effective to newly emerging

data services and was losing its edge to computer networking that met the low-cost but not the

reliability and security requirements. The first Internet protocol did not include security features;

however, its deployment expanded rapidly. n fact, information on the Internet network takes a

complex route, which is not under the control of the network itself, as compared with

information on the circuit-switched network. Thus, being a connectionless network with

distributed control, and operated by many small and medium-size network providers,

information was easily accessible and vulnerable to eavesdropping, data harvesting, and attacks.

The possibility that a third party may be able to harvest credit card information and health and

other personal records or misrepresenting data injected in the network has generated increasing

concern within industry and government alike. Similar to the Internet, the initial cellular wireless

network was very vulnerable to eavesdropping and calling-number mimicking. In fact, accessing

calling numbers and pin codes from the airwaves was extremely easy by an actor on the highway

using a properly converted receiver and a laptop. Since then, cellular wireless technology has

evolved, and new coding methods and protocol versions with enhanced security

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

5

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 3

BASICS OF CRYPTOGRAPHY

When Julius Caesar sent messages to his generals, he didn’t trust his messengers. So he

replaced every A in his messages with a D, every B with an E, and so on through the alphabet.

Only someone who knew the “shift by 3” rule could decipher his messages.

And so we begin. Data that can be read and understood without any special measures is called

plaintext or cleartext. The method of disguising plaintext in such a way as to hide its substance is

called encryption. Encrypting plaintext results in unreadable gibberish called ciphertext. You use

encryption to ensure that information is hidden from anyone for whom it is not intended, even

those who can see the encrypted data. The process of reverting ciphertext to its original plaintext

is called decryption.

Cryptography is the science of using mathematics to encrypt and decrypt data.

Cryptography enables you to store sensitive information or transmit it across insecure networks

(like the Internet) so that it cannot be read by anyone except the intended recipient. While

cryptography is the science of securing data, cryptanalysis is the science

of analyzing and breaking secure communication. Classical cryptanalysis involves an interesting

combination of analytical reasoning, application of mathematical tools, pattern finding, patience,

determination, and luck. Cryptanalysts are also called attackers. Cryptology embraces both

cryptography and cryptanalysis.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

6

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 4

SECURITY, CRYPTOGRAPHY AND PRIVACY

Until the 1980s and prior to the advent of the Internet, the communications

circuit-switched network was in general inaccessible; specialized networking know-how was

required to tap a twowire pair and eavesdrop (as shown in “spy” movies such as “James Bond”

and “Mission Impossible”) or to mimic signaling codes using the so-called “blue box” and

bypass-calling billing. Moreover, this network was not challenged with virus attacks and the like;

in fact, cyber-security is a modern term that did not exist until the spread of the Internet several

years ago. Thus, for many years, network security had not been a priority and had been

underemphasized or overlooked. However, the circuit-switched network was not flexible and

cost-effective to newly emerging data services and was losing its edge to computer networking

that met the low-cost but not the reliability and security requirements. The first Internet protocol

did not include security features; however, its deployment expanded rapidly. In fact, information

on the Internet network takes a complex route, which is not under the control of the network

itself, as compared with information on the circuit-switched network. Thus, being a

connectionless network with distributed control, and operated by many small land medium-size

network providers, information was easily accessible and vulnerable to eavesdropping, data

harvesting, and attacks. The possibility that a third party may be able to harvest credit card

information and health and other personal records or misrepresenting data injected in the

network has generated increasing concern within industry and government alike. Similar to the

Internet, the initial cellular wireless network was very vulnerable to eavesdropping and callingnumber mimicking. In fact, accessing calling numbers and pin codes from the airwaves was

extremely easy by an actor on the highway using a properly converted receiver and a laptop.

Since then, cellular wireless technology has evolved, and new coding methods and protocol

versions with enhanced security and authentication procedures have been added.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

7

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

The rapid spread of the Internet, and the lack of robust security features has

unleashed the appetite of bad actors for invading the network and its computers with destructive

results. Destructive programs that hide within other programs sneak into computers where they

execute instructions that harvest personal data, open classified files, destroy files, allow them to

clone themselves and propagate to other computers, flood the network and cause denial of

service, enlist personal computers to execute programs secretly, and so on. Current incidents

have placed network security on high national priority and at the forefront of research. For

instance, cyber-attacks, “stealth” attacks (attacks that do not modify data or leave Website

traces), and silent data extraction have been on the rise, as was reported to the “Internet Security

Alliance Briefing to White House Staff and Members of Congress” (M. K. Daly, September 16,

2004). The post-September-11th cyber-attack known as “Code Red” infected 150,000 computers

in just fourteen hours and two months later the attack “NIMDA” infected 86,000 computers. The

Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT) of Carnegie Melon University reported that by

2002, attacks would increase to 110,000 from 3,700 in 1998. Similarly, the Congressional

Research Service Report to Congress (April 2004) reported that, “Estimates of total worldwide

losses attributable to attacks in 2003 range from $13 billion due to viruses and worms only to

$226 billion for all forms of overt attacks.” And a report filed with the Federal Trade

Commission (see USA Today, April 1, 2005, p. D1), stated that electronic heists of credit card

numbers and other personal data account for one third of all complaints over the last three years.

These reports and others have raised serious concerns with government and industry. In response

to this, an Internet Security Alliance was formed between Carnegie Mellon University’s

Software Engineering Institute (SEI) and its CERT Coordination Center (CERT/CC) and

Electronic Industries Alliance (EIA), a federation of trade associations with more than 2,500

members.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

8

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 5

SYMMETRIC KEY CRYPTOGRAPHY

Symmetric-key algorithms are a class of algorithms for cryptography that use

trivially related, often identical, cryptographic keys for both decryption and encryption etc.

The encryption key is trivially related to the decryption key, in that they may be

identical or there is a simple transformation to go between the two keys. The keys, in practice,

represent a shared secret between two or more parties that can be used to maintain a private

information link.

Other terms for symmetric-key encryption are secret-key, single-key, shared-key,

one-key, and private-key encryption. Use of the last and first terms can create ambiguity with

similar terminology used in public-key cryptography.

Symmetric-key algorithms can be divided into stream ciphers and block ciphers.

Stream ciphers encrypt the bits of the message one at a time, and block ciphers take a number of

bits and encrypt them as a single unit. Blocks of 64 bits have been commonly used. The

Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) algorithm approved by NIST in December 2001 uses 128bit blocks.Symmetric ciphers are often used to achieve other cryptographic primitives than just

encryption.

Encrypting a message does not guarantee that this message is not changed while

encrypted. Hence often a message authentication code is added to a ciphertext to ensure that

changes to the ciphertext will be noted by the receiver. Message authentication codes can be

constructed from symmetric ciphers (e.g. CBC-MAC).

However, symmetric ciphers also can be used for non-repudiation purposes by

ISO 13888-2 standard.

Another application is to build hash functions from block ciphers. See one-way

compression function for descriptions of several such methods.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

9

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 6

IMPLEMENTATION TOOL – MATLAB 7.6

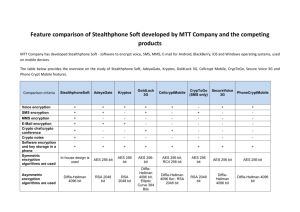

Fig. 1. MATLAB Symbol

MATLAB Is a program for doing numerical computation. It was

originally designed for solving linear algebra type problem using matrices. It’s name is derived

from MATrix LABort ary. MATLAB is also a programming language that currently is widely

used as a platform for developing tools for machine Learning.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

10

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

MATLAB is a commercial “Matrix Laboratory” package which operates as an

interactive programming environment. It is a mainstay of the Mathematics Department software

lineup and is also available for PC’s and Macintoshes and may be found on the CIRCA VAXes.

MATLAB is well adapted to numerical experiments since the underlying algorithms for Matlab’s

built in functions and supplied m-files on the standard libraries LINPACK and EISPACK.

Matlab program and script files always have filenames ending with “.m” ;the

programming language is exceptionally straightforward since almost every data object is

assumed to be in an array. Graphical output is available to supplement numerical results.

BUILDING MATRICES

Matlab has many types of matrices which are built into the system. You can

generate random matrices of other sizes and get help on the ‘rand’ command within matlab.

Another special matrix called a Hilbert matrix, is a standard example in numerical linear

algebra. A magic square is a matrix whoch has equal sum along rows and columns. You can

build matrices of your own with any entries that you may want.

BASIC FEATURES

MATLAB is case sensitive,that is “a” is not the same as “A.” if this proves to be

an annoyance, the command ‘casesen’ will toggle the case sensitivity off and on. The MATLAB

display only shows 5 digits in the default mode. The fact is that MATLAB always keeps and

computes in a double precision 16 decimal places and rounds the display to 4 digits.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

11

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 7

AES WITH CBC ALGORITHM

The AES algorithm consists of a complex non-linear core function, which is iterated

multiple times starting from the incoming plain text data block. Each iteration is called a

“round”. The round function is slightly modified for the final round and there is an additional

pre-processing round at the start of every encryption. The number of “rounds” required depends

on the selected key size. For a key size of 128-bit there are 10 rounds, for a 192-bit key there are

12 rounds, and for a 256-bit key there are 14 rounds. The consequence of this is that the longer

key sizes do take slightly more time to process. Each round of AES requires a unique 128-bit

round key schedule that is generated from the supplied 128-bit, 192-bit or 256-bit AES key using

a key expansion algorithm. For 128-bit keys one needs 11 key schedules, for 192-bit keys one

needs 13 key schedules and for 256-bit keys one needs 15 key schedules. The key expansion

process can be accomplished in one of two ways. For the encryption the round key schedules can

be generated “on the fly” in real-time when they are required by the encryption algorithm. This is

especially useful if the AES keys need to change on a regular basis. If the AES keys do not get

changed too often then the round key schedules may be generated off-line and stored in internal

RAM for subsequent use.

Each iteration in the AES with CBC algorithm mainly consists of only four cryptographic

algorithm steps. They are as follows :

(i)

Sub Bytes

(ii)

Shift Rows

(iii)

Mix Columns

(iv)

Add Round Key

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

12

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 8

HIGH LEVEL DESCRIPTION OF THE

ALGORITHM

8.1 The SubBytes step

In the SubBytes step, each byte in the array is updated using an 8-bit substitution box,

the Rijndael S-box. This operation provides the non-linearity in the cipher. To avoid attacks

based on simple algebraic properties, the S-box is chosen as a 16x16 look up table with

hexadecimal values. The S-box is also chosen to avoid any fixed points.

Fig. 2. SubBytes

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

13

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

8.2 The ShiftRows step

The ShiftRows step operates on the rows of the state; it cyclically shifts the bytes in each

row by a certain offset. For AES, the first row is left unchanged. Each byte of the second row is

shifted one to the left. Similarly, the third and fourth rows are shifted by offsets of two and three

respectively.

Fig. 3. ShiftRows

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

14

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

8.3 The MixColumns step

In the MixColumns step, each column is multiplied by the known matrix that for the 128

bit key. The multiplication operation is defined as: multiplication by 1 means leaving unchanged,

multiplication by 2 means shifting byte to the left and multiplication by 3 means shifting to the

left and then performing xor with the initial unshifted value. In more general sense, each column

is treated as a polynomial and is then multiplied modulo x4+1 with a fixed polynomial c(x) =

0x03 · x3 + x2 + x + 0x02. The coefficients are displayed in their hexadecimal equivalent of the

binary representation of bit polynomials.

Fig. 4. MixColumns

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

15

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

8.4 The AddRoundKey step

In the AddRoundKey step, the subkey is combined with the state. For each round, a

subkey is derived from the main key using Rijndael's key schedule; each subkey is the same size

as the state. The subkey is added by combining each byte of the state with the corresponding byte

of the subkey using bitwise XOR.

Fig. 5. AddRoundKey

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

16

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 9

FLOW DIAGRAM

Fig. 6. Flowchart

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

17

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 10

BLOCK DIAGRAMS WITH DESCRIPTIONS

10.1 Standard Encryption Core AES

This entity is an AES encryption component that uses an external key expander. The

component processes each round in a single clock cycle. Plain text input, round key schedule

input and cipher text output ports are 128 bits wide.

Fig. 7. Standard Encryption Core AES

When the start signal is asserted, input data is loaded and a new encryption operation is

started. After a latency of 11, 13 or 15 master clock cycles (depending on the key size of 128,

192 or 256 bits) the ready signal is asserted and the cipher text output is valid. The round key

index cycles through all needed values and is valid one clock cycle before the round key

schedule data is required. This allows the use of external synchronous RAM to store the round

key schedules. A new encryption operation can be started whenever the round key index is zero.

One clock cycle later the output of a previous operation becomes available.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

18

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

10.2 Standard Decryption Core AES

This entity is an AES decryption component that uses an external key expander. The

component processes each round in a single clock cycle. Cipher text input, round key schedule

input and plain text output ports are 128 bits wide.

Fig. 8. Standard Decryption Core AES

When the start signal is asserted, input data is loaded and a new decryption operation is

started. After a latency of 11, 13 or 15 master clock cycles (depending on the key size of 128,

192 or 256 bits) the ready signal is asserted and the plain text output is valid. The round key

index cycles through all needed values and is valid one clock cycle before the round key

schedule data is required. This allows the use of external synchronous RAM to store the round

key schedules. A new decryption operation can be started whenever the round key index is zero.

One clock cycle later the output of a previous operation becomes available.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

19

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

10.3 Standard Encryption/Decryption Core AES

This entity is a combined encryption/decryption component with external key expander.

The component processes each round in a single clock cycle. Plain/cipher text input, round key

schedule input and cipher/plain text output ports are 128 bits wide. When the start signal is

asserted, input data is loaded and a new operation is started. Depending on the state of a select

signal the operation is either encryption or decryption. After a latency of 11, 13 or 15 master

clock cycles (depending on the key size of 128, 192 or 256 bits) the ready signal is asserted and

the plain text output is valid. The round key index cycles through all needed values and is valid

one clock cycle before the round key schedule data is required. This allows the use of external

synchronous RAM to store the round key schedules. A new operation can be started whenever

the round key index is zero. One clock cycle later the output of a previous operation becomes

available.

Fig. 9. Standard Encryption/Decryption Core AES

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

20

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 11

INPUTS & OUTPUTS

INPUTS

Data to be encrypted such as text, image, file etc. of any size. Data is treated as matrix

and is encrypted block by block.

User defined Key of any length can be used to encrypt the data matrix.

INTERNALLY GENERATED

A Predefined Key is used to encrypt the User defined Key.

Substitution Box & Inverse Substitution Box for Sub Bytes algorithm.

Polymat & Inverse Polymat matrices for Mix Column algorithm.

OUTPUTS

The result of AES encryption is an encrypted data matrix of size 128 bit larger than the

input data matrix.

The result of AES decryption is a decrypted data matrix of size same as input data matrix.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

21

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 12

KEY EXPANSION ALGORITHM

With AES encryption, the secret key is known to both the sender and the receiver.

The AES algorithm remains secure, the key cannot be determined by any known means, even if

an eavesdropper knows the plaintext and the cipher text. The AES algorithm is designed to use

one of three key sizes (Nk). AES-128, AES-196 and AES-256 use 128 bit (16 bytes, 4 words),

196 bit (24 bytes, 6 words) and 256 bit (32 bytes, 8 words) key sizes respectively. These keys,

unlike DES, have no known weaknesses. All key values are equally secure thus no value will

render one encryption more vulnerable than another. The keys are then expanded via a key

expansion routine for use in the AES cipher algorithm.This key expansion routine can be

performed all at once or ‘on the fly’ calculating words as they are needed. The key expansion

algorithm is shown below :

void KeyExpansion(byte[] key, word[] w, int Nw) {

int Nr = Nk + 6;

w = new byte[4*Nb*(Nr+1)];

int temp;

int i = 0;

while ( i < Nk) {

w[i] = word(key[4*i], key[4*i+1], key[4*i+2],

key[4*i+3]);

i++;

}

i = Nk;

while(i < Nb*(Nr+1)) {

temp = w[i-1];

if (i % Nk == 0)

temp = SubWord(RotWord(temp)) ˆ Rcon[i/Nk];

else if (Nk > 6 && (i%Nk) == 4)

temp = SubWord(temp);}

w[i] = w[i-Nk] ˆ temp;

i++;

}

Table 1. Key Expansion

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

22

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

12.1 KEY EXPANSION – FLOW DIAGRAM

Fig. 10 Key Expansion -Flow Diagram

The predefined key is expanded into 11 key matrices using a key expansion algorithm.

The generated 11 key matrices are used to perform AES encryption of user defined key.

The encrypted user defined key is again expanded into 11 key matrices using the same

key expansion algorithm.

The final 11 key matrices are used to perform AES encryption of input data.

The same 11 key matrices are used to perform AES decryption of encrypted data in the

reverse order.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

23

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 13

SUBSTITUTION BOX (SBox)

Table 2 SBox

The numbers 0 to 255 are arranged in random in SBox.

Eg: A number 12 is replaced with 13th element of SBox, ie. 254.

This avoids linearity.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

24

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

13.1 INVERSE SUBSTITUTION BOX (iSBox)

Table 3 iSBox

Inverse SBox is generated by replacing 0 to 255 numbers by one position greater than the

corresponding position in SBox.

Eg : 254 is replaced by 255th element in iSBox which is 12.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

25

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

13.2 MIXCOLUMN MATRICES

Table 4 MixColumn matrices

Matrix multiplication is done between data matrix and polymat in encryption and with

inverse polymath in decryption.

Bitshift and bitxor are used for matrix multiplication and output values are limited within

255 (GF(2^8) – Galois Field).

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

26

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 14

AES ENCRYPTION PROCEDURE

Length of Plain Data is made to a multiple of 16 and divided into 4X4 matrices.

Each 4X4 matrix is encrypted separately.

In first round, add round key is performed between first state matrix and first key matrix.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

27

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

In rounds 2 to 10, Sub bytes is performed to state matrix.

It is followed by shift rows to left.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

28

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

Then mixcolumn algorithm is performed followed by add round key.

Keys 2 to 10 are used in add round key for corresponding rounds.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

29

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

In the last round sub bytes algorithm is performed in state matrix.

It is followed by shift rows to left.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

30

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

At last, add round key is performed to state matrix with key 11 in last round to obtain the

encrypted data.

Same procedure is repeated in remaining 4X4 blocks.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

31

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 15

AES DECRYPTION PROCEDURE

Each 4X4 encrypted data matrix is decrypted separately.

In first round, add round key is performed between state matrix and last key matrix.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

32

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

In rounds 2 to 10, shift rows to right is performed to state matrix.

It is followed by inverse sub bytes.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

33

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

Then add round key is performed followed by inverse mixcolumn algorithm.

Keys 2 to 10 are used in add round key for corresponding rounds in reverse order.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

34

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

In the last round shift rows to right is performed to state matrix.

It is followed by inverse sub bytes algorithm.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

35

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

At last, add round key is performed to state matrix with key 1 in last round to obtain the

decrypted data.

Same procedure is repeated in remaining 4X4 blocks.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

36

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 16

ALGORITHMS

MAIN FUNCTION – CryptAES

Step 1: Start

Step 2: Find length of input data

Step 3: Reshape input data and use integers if possible

Step 4: Encode if the Command starts with 'e' or 'E', decode otherwise

Step 5: Initialize AES parameters, create CBC initial vector for encoding

Step 6: Process the data – encode or decode.

Step 7: Clear secrets

Step 8: Stop

ENCRYPT FUNCTION – EncodeI

Step 1: Start

Step 2: Initialization of parameters to local variables (SBox & Key)

Step 3: Allocate output as an array of zero with length greater than input data length

Step 4: Initialize substitution for cyclical shift to the left

Step 5: Set CBC IV as first block

Step 6: Open wait bar

Step 7: Iterate steps 8 to 18 until DataLen/16 reached.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

37

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

Step 8: Copy 4x4 block from input data to the state matrix and apply the CBC mask

Step 9: Perform first round - Add RoundKey.

Step 10: Iterate steps 11 to 15 nine times (Rounds 2 to 10)

Step 11: Perform SubBytes and Shift Rows to left algorithms

Step 12: Perform Mix Columns algorithm

Step 13: Create polynomial matrix for Mix columns

Step 14: Divide msb with irreducible decimal 283 to limit upto 255

Step 15: Perform Add Roundkey.

Step 16: Encrypted data is new CBC mask

Step 17: Perform Round 11 - subbyte, shiftrows, addroundkey

Step 18: Process the wait bar

Step 19: Close the wait bar.

Step 20: Clear secrets

Step 21: Stop

DECRYPT FUNCTION – DecodeI

Step 1: Start

Step 2: Initialization of parameters to local variables (SBox & Key)

Step 3: Allocate output as an array of zero with length less than encrypted data length

Step 4: Initialize substitution for cyclical shift to the right

Step 5: Set first block as initial CBC IV

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

38

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

Step 6: Open wait bar

Step 7: Iterate steps 8 to 18 until DataLen/16 reached.

Step 8: Use encrypted data block as CBC value for the block

Step 9: Perform last round - Add RoundKey.

Step 10: Iterate steps 11 to 15 nine times (Rounds 10 down 2)

Step 11: Perform Inverse SubBytes and Shift Rows to right algorithms

Step 12: Perform Add Roundkey.

Step 13: Perform Inverse Mix Columns algorithm

Step 14: Create polynomial matrix for inverse Mix columns

Step 15: Divide msb with irreducible decimal 283 to limit upto 255

Step 16: Apply old CBC mask to decrypted data

Step 17: Perform Round 1 – inverse subbyte, shiftrows to right, addroundkey

Step 18: Process the wait bar

Step 19: Close the wait bar.

Step 20: Clear secrets

Step 21: Stop

INITIALISATION OF AES PARAMETERS Function - Init

Step 1: Start

Step 2: Initialize parameters, create CBC IV

Step 3: Create the S-box and the inverse S-box

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

39

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

Step 4: Call function ExpandCipher for expansion of pre defined key

Step 5: Limit the range of values to 0:255

Step 6: Limit or expand key to 16 bytes

Step 7: Encrypt user defined key with expanded pre defined key

Step 8: Call function ExpandCipher for expansion of encrypted key

Step 9: Stop

ROUND KEY EXPANSION Function – ExpandCipher

Step 1: Start

Step 2: Expand the 16-byte cipher to the 4x4x11 array

Step 3: Copy 16 bytes column-wise

Step 4: Perform RounKey Expansion algorithm

Step 5: Stop

CALLING PROGRAMS (Calls CryptAES in AES GUI)

TEXT DATA ENCRYPTION Function

Step 1: Start

Step 2: Get the input text from Edit Text Box

Step 3: Find the input Data length

Step 4: If it is not a multiple of 16, append it with ‘#’ to make it a multiple of 16

Step 5: Get the key from Edit Text Box

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

40

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

Step 6: Perform CryptAES speed test

Step 7: Call CryptAES

Step 8: Set encrypted data in the Edit Text Box

Step 9: Stop

TEXT DATA DECRYPTION Function

Step 1: Start

Step 2: Get the key from Edit Text Box

Step 3: Perform CryptAES speed test

Step 4: Call CryptAES.

Step 5: Set encrypted data in the Edit Text Box

Step 6: Stop

IMAGE DATA READ Function

Step 1: Start

Step 2: Read the image by browsing it

Step 3: Show the image on the respective axis

Step 4: Find the size of image in 3 dimensions

Step 5: Make all dimensions multiple of 16 by appending with ‘0’

Step 6: Stop

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

41

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

IMAGE DATA ENCRYPTION Function

Step 1: Start

Step 2: Get the key from Edit Text Box

Step 3: Perform CryptAES speed test

Step 4: Call CryptAES.

Step 5: Show the encrypted image on respective axis

Step 6: Stop

IMAGE DATA DECRYPTION Function

Step 1: Start

Step 2: Get the key from Edit Text Box

Step 3: Perform CryptAES spee test

Step 4: Call CryptAES

Step 5: Show the decrypted image on respective axis

Step 6: Stop

FILE ENCRYPTION Function

Step 1: Start

Step 2: Open the clear file

Step 3: Set the pathname and filename in the Edit Text Box.

Step 4: If File ID less than ‘0’, Cannot read the file

Step 5: Read the file in binary

Step 6: Close the file

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

42

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

Step 7: Find data length and if data length is not a multiple of 16, append it with ‘0’ to make it

multiple of 16.

Step 8: Append dummy data to check correct key.

Step 9: Get the key from Edit Text Box

Step 10: Call CryptAES

Step 11: Save the cipher file by writing in binary.

Step 12: Close the file

Step 13: Stop.

FILE DECRYPTION Function

Step 1: Start

Step 2: Open the cipher file

Step 3: Set the pathname and filename in the Edit Text Box.

Step 4: If File ID less than ‘0’, Cannot read the file

Step 5: Read the file in binary

Step 6: Close the file

Step 7: Get the key from Edit Text Box

Step 8: Call CryptAES

Step 9: Find data length

Step 10: Check correct key by comparing with dummy key appended.

Step 11: Save the clear file by writing in binary.

Step 12: Close the file

Step 13: Stop.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

43

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 17

BLOCK CIPHER: MODES OF OPERATION

In cryptography, modes of operation enable the repeated and secure use of a block

cipher under a single key. A block cipher by itself allows encryption only of a single data block

of the cipher's block length. When targeting a variable-length message, the data must first be

partitioned into separate cipher blocks. Typically, the last block must also be extended to match

the cipher's block length using a suitable padding scheme. A mode of operation describes the

process of encrypting each of these blocks, and generally uses randomization based on an

additional input value, often called an initialization vector, to allow doing so safely.

Modes of operation have primarily been defined for encryption and

authentication. Historically, encryption modes have been studied extensively in regard to their

error propagation properties under various scenarios of data modification. Later development

regarded integrity protection as an entirely separate cryptographic goal from encryption. Some

modern modes of operation combine encryption and authentication in an efficient way, and are

known as authenticated encryption modes.

While modes of operation are commonly associated with symmetric encryption,

they may also be applied to public-key encryption primitives such as RSA in principle (though in

practice public-key encryption of longer messages is generally realized using hybrid encryption).

17.1 INITIALIZATION VECTOR (IV)

An initialization vector (IV) is a block of bits that is used by several modes to

randomize the encryption and hence to produce distinct cipher texts even if the same plaintext is

encrypted multiple times, without the need for a slower re-keying process.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

44

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

An initialization vector has different security requirements than a key, so the IV

usually does not need to be secret. However, in most cases, it is important that an initialization

vector is never reused under the same key. For CBC (Cipher Block Chaining), reusing an IV

leaks some information about the first block of plaintext, and about any common prefix shared

by the two messages. In CBC mode, the IV must, in addition, be unpredictable at encryption

time; in particular, the (previously) common practice of re-using the last cipher text block of a

message as the IV for the next message is insecure (for example, this method was used by SSL

2.0). If an attacker knows the IV (or the previous block of cipher text) before he specifies the

next plaintext, he can check his guess about plaintext of some block that was encrypted with the

same key before (this is known as the TLS CBC IV attack).

17.2 PADDING

A block cipher works on units of a fixed size (known as a block size), but

messages come in a variety of lengths. So some modes (namely ECB and CBC) require that the

final block be padded before encryption. Several padding schemes exist. The simplest is to add

null bytes to the plaintext to bring its length up to a multiple of the block size, but care must be

taken that the original length of the plaintext can be recovered; this is so, for example, if the

plaintext is a C style string which contains no null bytes except at the end. Slightly more

complex is the original AES method, which is to add a single one bit, followed by enough zero

bits to fill out the block; if the message ends on a block boundary, a whole padding block will be

added. Most sophisticated are CBC-specific schemes such as cipher text stealing or residual

block termination, which do not cause any extra cipher text, at the expense of some additional

complexity. Schneier and Ferguson suggest two possibilities, both simple: append a byte with

value 128 (hex 80), followed by as many zero bytes as needed to fill the last block, or pad the

last block with n bytes all with value n.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

45

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

17.3 ELECTRONIC CODE BOOK

The simplest of the encryption modes is the electronic codebook (ECB) mode.

The message is divided into blocks and each block is encrypted separately.

Fig. 11 Electronic Code Book

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

46

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

17.4 CIPHER BLOCK CHAINING

CBC mode of operation was invented by IBM in 1976. In the cipher-block

chaining (CBC) mode, each block of plaintext is XORed with the previous ciphertext block

before being encrypted. This way, each ciphertext block is dependent on all plaintext blocks

processed up to that point. Also, to make each message unique, an initialization vector must be

used in the first block.

Fig. 12 Cipher Block Chaining

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

47

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

If the first block has index 1, the mathematical formula for CBC encryption is

while the mathematical formula for CBC decryption is

CBC has been the most commonly used mode of operation. Its main drawbacks

are that encryption is sequential (i.e., it cannot be parallelized), and that the message must be

padded to a multiple of the cipher block size. One way to handle this last issue is through the

method known as ciphertext stealing.

Note that a one-bit change in a plaintext affects all following ciphertext blocks. A

plaintext can be recovered from just two adjacent blocks of ciphertext. As a consequence,

decryption can be parallelized, and a one-bit change to the ciphertext causes complete corruption

of the corresponding block of plaintext, and inverts the corresponding bit in the following block

of plaintext.

The disadvantage of this method is that identical plaintext blocks are encrypted into identical

ciphertext blocks; thus, it does not hide data patterns well. In some senses, it doesn't provide

serious message confidentiality, and it is not recommended for use in cryptographic protocols at

all. A striking example of the degree to which ECB can leave plaintext data patterns in the

ciphertext is shown below; a pixel-map version of the image on the left was encrypted with ECB

mode to create the center image, versus a non-ECB mode for the right image.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

48

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

Fig 13. Original Image

AES WITH CBC

Fig. 14 Encrypted using ECB

mode

Fig. 15 Encrypted using CBC

results in pseudo-randomness

The image on the right is how the image might appear encrypted with CBC, —

indistinguishable from random noise. Note that the random appearance of the image on the right

does not ensure that the image has been securely encrypted; many kinds of insecure encryption

have been developed which would produce output just as 'random-looking'.

ECB mode can also make protocols without integrity protection even more

susceptible to replay attacks, since each block gets decrypted in exactly the same way. For

example, the Phantasy Star Online: Blue Burst online video game uses Blowfish in ECB mode.

Before the key exchange system was cracked leading to even easier methods, cheaters repeated

encrypted "monster killed" message packets, each an encrypted Blowfish block, to illegitimately

gain experience points quickly.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

49

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 18

COMPARISON WITH PREVIOUS STANDARDS

This is impressive and is true because the size of the AES key is exponentially

larger than the DES key. However, DES was broken earlier than expected in part because CPU

processing speeds have also been increasing exponentially. If we assume that CPU’s will

continue to increase exponentially, per Moore’s Law which states CPU processor speed will

double every 18 months, AES-128 will still remain secure for 109.5 years, AES-196 will remain

secure for 211.5 years and AES-256 will remain secure for 301.5 years. While the demise of

Moore’s Law has been considered imminent for the past 20 years or so, and there is no true end

in sight,

it seems unlikely Moore’s Law will continue for another 300 years.

Also the

assumption in these statements is attacks more efficient than brute force will not be found.

Key Length

(Nk words)

4

6

8

AES-128

AES-192

AES-256

Rijndael - 128

Rijndael - 192

Rijndael - 256

DES

*

Expanded

Key Length

(words)

Block Size Number of

(Nb words) Rounds Nr

44

4

10

52

4

12

60

4

14

4

10

4

44

6

12

8

14

4

12

6

52

6

12

8

14

4

14

8

60

6

14

8

14

*

256

2

16

2

of 64 bits, only 56 are used

Table 5 AES, DES, Rijndael Comparisons

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

50

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

18.1 AES vs DES AT A GLANCE

Table 6. AES vs DES

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

51

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 19

ATTACKS AND SECURITY

There are several known methods for attacking block ciphers. The Rijndael

algorithm was designed to be resistant to all the known methods.

The four most common are

linear, differential, XSL and Side Channel Attacks.

19.1 DIFFERENTIAL CRYPTANALYSIS

Differential Cryptanalysis is the study of how differences in input affect

differences in output. Certain values for keys in DES made the encryption algorithm vulnerable

to linear analysis. Increasing the number of rounds greatly reduces the success of differential

attacks. The authors estimated that 5 rounds would make the difficulty of differential analysis

about as hard as a brute force attack on the key. They then added a more rounds as a buffer for

added security.

19.2 LINEAR CRYPTANALYSIS

Linear Crytanalysis is the study of correlations between input and output.

SubBytes & MixColumns are designed to frustrate Linear Analysis.

19.3 XSL CRYPTANALYSIS

Linear Cryptanalysis is an attack method developed in 2002. There is a lot of

debate over how successful XSL can be. The developers claim it will be able to break AES. But

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

52

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

many mathematicians and cryptography experts have their doubts. Their feeling is that even if

XSL can break AES, it cannot do so well, instead of taking 149 trillion years to brute force an

attack on the key, XSL might be able to find the key in just 140 trillion years, not much of a

benefit.

XSL is a detailed study of the mathematics behind an encryption algorithm. Its run

time is hard to calculate as it uses complex heuristics. Essentially it tries to reduce the cipher to a

series of mathematical equations and then solves those equations. Right now XSL has reduced

AES to a series of 8000 non-linear equations and 1600 unknowns. If a method can be found to

solve these equations AES can be broken.

19.4 SIDE CHANNEL ATTACKS

Side channel Attacks are attacks on the implementation of AES, not on the input

or the AES cipher text. It attempts to correlate various measurements of the encrypting tool with

time in an attempt to guess the key. A professor at MIT,9 encoded an AES algorithm on his

computer, an 850MHz, Pentium III running FreeBSD 4.8 and by measuring time delays between

the CPU and memory was able to successfully guess the key in under 100 minutes. There is a

correlation between the index of an array and the time it takes to get the results back. This is due

to the physical location of the data in the memory device. Data closer to the output lead will not

take as much time to be retrieved as data further away, because it will not take as long for the

signal to propagate its way out of the chip.

He feels he can improve on this time. After running a few thousand encryptions

he spent about an hour studying the results of his measurements. After studying the data, there

were many repetitions to avoid noise, he concluded the key was one of several possibilities. By

trying each one, he was able to find the key.

He believes this analysis process can be

programmed, cutting the time down to just a few minutes.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

53

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

The method of measuring time delays in memory requests are called timing attacks.

Power attacks attempt to measure power consumption by the CPU.

It takes more power to

switch 8 bits than it takes to switch 1 bit. Some are also now measuring radiation levels from

CPU’s and gaining knowledge of its inner workings.

There are several techniques which can greatly frustrate side channel attacks. 1)

Avoid use of arrays. Compute values of SBOX and rCon to avoid timing attacks. 2) Design

algorithms and devices to work with constant time intervals. (independent of key and plaintext.)

Study your device spec sheets, and insist on accurate data. For example you should know which

takes longer, XOR or shift operations. 3) Use same memory throughout, remember, cache is

faster than DRAM. 4) Compute Key Expansion on the fly. Don’t compute the Key Expansion

and then reference it from memory. 5) Utilize pipelining to stabilize CPU power consumption.

6) Use specialized chips whenever possible, right now they are significantly faster than CPU’s

and require extremely expensive equipment for side channel attack measurements.

NIST was aware of side channel attacks when evaluating all the finalists.

Comparing the Rijndael algorithm security against side channel attacks to the other four finalists

considered by NIST they concluded:

Rijndael and Serpent use only Boolean operations, table lookups, and fixed

shifts/rotations. These operations are the easiest to defend against attacks.

Twofish uses addition, which is somewhat more difficult to defend against attacks.

MARS and RC6 use multiplication/division/squaring and/or variable shift/rotation. These

operations are the most difficult to defend.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

54

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 20

ADVANTAGES

High data security.

Unclassified.

Publicly disclosed.

Available royalty-free, worldwide.

Capable of handling a block size of at least 128 bits.

At a minimum, capable of handling key sizes of 128, 192, and 256 bits.

Computational efficiency and memory requirements on a variety of software and

hardware including smart cards.

Flexibility, simplicity and ease of implementation.

AES is extremely fast compared to other block ciphers. (though there are tradeoff

between size and speed)

The round transformation is parallel by design. This is important in dedicated hardware

as it allows even faster execution.

AES was designed to be amenable to pipelining.

The cipher does not use arithmetic operations so has no bias towards big or little endian

architectures.

AES is fully self-supporting. Does not use SBoxes of other ciphers, bits from Rand

tables, digits of or any other such jokes. (Their quote, not mine)

AES is not based on obscure or not well understood processes.

The tight cipher and simple design does not leave enough room to hide a trap door.

The AES will be the government's designated encryption cipher. The expectation is that

the AES will suffice to protect sensitive (unclassified) government information until at least the

next century. It is also expected to be widely adopted by businesses and financial institutions.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

55

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 21

APPLICATIONS

AES (256-bit) is used to encrypt 900 MHz and 2.4 GHz data communications on

MaxStream Radio Modems.

AES is used to encrypt video games on the Sony PSP.

AES is an encryption algorithm used by the IEEE 802.11i (WPA2) standard.

AES in CBC mode is the default cipher used in OpenSSH protocol 2 connections.

AES is employed in WinRAR when encryption is used.

AES is used by Apple's(TM) later OS's using 128-bit encryption

AES is used by Winzip 9.0. and Winrar

.

CHAPTER 22

LIMITATIONS

The inverse cipher is less suited to smart cards, as it takes more codes and cycles.

The cipher and inverse cipher make use of different codes and/or tables.

In hardware, The inverse cipher can only partially re-use circuitry which implements the

cipher.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

56

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 23

CONCLUSION

The security of communications networks is of extreme importance, as it impacts

the privacy of client data as well as national security.

Unlike DES, which has no parameterization and hence no flexibility, AES permits

upgrades as necessary. As technology improves, and as the true strength of AES algorithms

becomes better understood through analysis, the most appropriate parameter values can be

chosen.

The new AES will certainly become the de facto standard for encrypting

all forms of electronic information, replacing DES. AES-encrypted data is unbreakable in the

sense that no known cryptanalysis attack can decrypt the AES cipher text without using a bruteforce search through all possible 256-bit keys.

The major obstacle we found when implementing an AES was that the official

specification document was written from a mathematician's point of view rather than from a

software developer's point of view. In particular, the specification assumes that the reader is

fairly familiar with the GF(28) field and it leaves out a few key facts regarding GF(28)

multiplication that are necessary to correctly implement AES. We have tried here to remove the

mystery from AES, especially surrounding GF(28) field multiplication.

However, having this code in your skill set will remain valuable for a number of

reasons. This implementation is particularly simple and will have low resource overhead. In

addition, access to and an understanding of the source code will enable you to customize the

AES class and use any implementation of it more effectively.

Security is no longer an afterthought in anyone's software design and

development process. AES is an important advance and using and understanding it will greatly

increase the reliability and safety of your software systems.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

57

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 24

REFERENCES

1. AES page available via http://www.nist.gov/CryptoToolkit.

2. Computer Security Objects Register (CSOR): http://csrc.nist.gov/csor/.

3. J. Daemen and V. Rijmen, AES Proposal: Rijndael, AES Algorithm Submission,

September 3, 1999, available at http://www.nist.gov/.

4. J. Daemen and V. Rijmen, The block cipher Rijndael, Smart Card research and

Applications, LNCS 1820, Springer-Verlag, pp. 288-296.

5. B. Gladman’s AES related home page

http://fp.gladman.plus.com/cryptography_technology/.

6. A. Lee, NIST Special Publication 800-21, Guideline for Implementing Cryptography in

the Federal Government, National Institute of Standards and Technology, November

1999.

7. A. Menezes, P. van Oorschot, and S. Vanstone, Handbook of Applied Cryptography,

CRC Press, New York, 1997, p. 81-83.

8. J. Nechvatal, et. al., Report on the Development of the Advanced Encryption Standard

(AES), National Institute of Standards and Technology, October 2, 2000, available at

http://www.nist.gov/.

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

58

College of Engineering Munnar

Major Project ’11

AES WITH CBC

CHAPTER 25

APPENDIX

Dept. of Electronics & Communication

59

College of Engineering Munnar