View/Open - Lirias

advertisement

6TH PH.D SEMINAR OF THE INTERNATIONAL

TELECOMMUNICATIONS SOCIETY

IMINDS OFFICES

VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT BRUSSEL,

PLEINLAAN 9, 2ND FLOOR

TITLE: REGIONALIZING REFORM OF TELECOMMUNICATION

SECTOR REGULATION IN THE EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY

(EAC): LESSONS FROM THE EXPERIENCE OF THE EUROPEAN

UNION (EU)

SUBMITTED BY:

JOSEPH KARIUKI NYAGA (PHD CANDIDATE)

FACULTY OF LAW - KU LEUVEN

(Email: joseph.nyaga@law.kuleuven.be)

INTERDISCIPLINARY CENTRE FOR LAW & ICT (ICRI) IMINDS

SINT-MICHIELSSTRAAT 6, 3000 LEUVEN (BELGIUM)

PROMOTORS:

PROF. DR. PEGGY VALCKE AND PROF. DR. JOS DUMORTIER

1

TABLE OF CONTENT:

1. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………3

1.1.

1.2.

1.3.

Principal research question:……………….…………………………5

Hypothesis:……………………………..………………………………5

Policy relevance:……………………………………...………………..5

2. LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK OF THE EAC………6

2.1. ICT developments in the EAC……………………………………….9

3. ASSESSMENT OF THE EAC TELECOMMUNICATION POLICIES,

REGULATORY AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORKS…………..10

3.1.

3.2.

3.3.

3.4.

3.5.

Divergences in telecommunications policy frameworks……….11

Divergences in institutional arrangement………………………..13

Divergences in regulatory frameworks…………………………...14

Convergence of the ICT sector in the EAC……………………….15

Implication of the inconsistencies to regulation…………………17

4. THE EXPERIENCE OF THE EUROPEAN UNION (EU)………………18

4.1.

4.2.

4.3.

Motivation of the EU as a case study………………………………18

The EU’s electronic communications regulatory framework

(ECRF)………………………………………………………………….20

Lessons from the experience of the EU……………………………23

5. RECOMMENDATIONS…………………………………………………..27

5.1.

5.2.

Regionalizing EAC regulatory framework……………………….27

Harmonization of Regulatory Frameworks in EAC……………..28

6. CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………..32

2

ABSTRACT

In the East African community (EAC), there has been an increasing recognition that

significant welfare gains could be realized through deep forms of regional integration

which entail harmonization of legal, regulatory and institutional frameworks for the

telecommunication sector. Implementation of the EAC common market and rapid

technological progress especially in mobile wireless technology, have made greater

coordination and harmonization of telecommunications policy more attractive.

Moreover, the EAC consists of less wealthy nations and therefore an interest in

regionalization is essential as a means to pool regulatory resources. This paper assesses

the potential gains from regionalized telecommunications policy in the EAC. The paper

seeks to assist stakeholders in the EAC and Member States in designing an effective

regional regulatory process. To this end, the paper: (i) discusses how EAC regional

cooperation can overcome national limits in technical expertise, enhance the capacity of

Member States to commit to stable regulatory policy in the EAC and ultimately

facilitate infrastructure investment in the region; (ii) identifies trade-distorting

regulations that inhibit opportunities for regional telecommunication development and

so are good candidates for regional negotiations that reduce indirect market entry

barriers; (iii) discusses the EU’s ongoing reforms towards a single market for electronic

communication for a connected continent as a case study that the EAC can draw lessons

from and there after describes substantive elements of a harmonized regional

regulatory policy that can deliver performance benefits.

Keywords: Telecom reforms, legislation, regulation, regional, East African Community.

1. INTRODUCTION

The EAC has a common market in place since 2010, therefore, relevant market areas of

the telecommunications industry transcend national borders, and little regulation in this

sector has purely domestic effects. EAC Member States currently deal with

telecommunications policy as a domestic concern, each with its own distinct and

dissimilar policy and regulatory regimes. Establishment of EAC common market and

rapid technological progress, especially in mobile wireless technology, have made

greater coordination and harmonization of telecommunications policy more attractive.

Moreover, the EAC consist of less wealthy Member States and are therefore interested

in regionalization as a means to pool regulatory resources.

3

The case for regionalization of telecommunication reforms in the EAC is hence based on

three reasons:

First, as telecommunication liberalization has reduced the role of tariffs and quotas in

affecting the ability of a service provider to compete in regional markets, inefficiencies

in infrastructure industries are more likely to determine the regional competitiveness of

domestic industries. Specifically, inefficient domestic infrastructure can cause otherwise

efficient national firms to lose both domestic and regional market share to firms from

countries with better infrastructure.

Second, domestic infrastructure policies can create substantial indirect market entry

barriers. For example, a highly inefficient telecommunication sector can effectively

protect inefficient domestic service providers from competition from superior regional

service providers by increasing the advantage of close proximity between service

providers and consumers.

Third, both economic integration and technological progress have caused the natural

market areas of infrastructure industries to expand, frequently transcending national

borders. Telecommunications sector operate more efficiently if its networks are

organized according to the patterns of transactions, and liberalization. This has made

these patterns increasingly international. Moreover, adjacent networks frequently

minimize costs by sharing capacities to take advantage of differences in the timepatterns of usage of infrastructure services during the day and year. Thus, regulation in

these sectors rarely has purely domestic effects, and when it does, the reason often is

that Member States within the EAC region are taking advantage of opportunities for

integrating their networks.

Although infrastructure reform programs in the EAC differ among the Member States,

most are based on creating market institutions and some degree of competition. The

purpose of these reforms is to generate more powerful financial incentives for service

providers to improve the performance of the sector. The needed regional reforms

should have three common elements:

(1) Corporatizing and usually privatizing incumbent operators; (2) permitting and even

encouraging competition in the markets that are still protected monopolies; and (3)

creating a regional regulatory body that is independent from the incumbent operators.

Regionalization of at least some elements of reform is attractive because it contributes to

the efficiency goals of policy reform while sidestepping some of the political obstacles

to effective reform. Infrastructure reform, when implemented in each Member State

independently, can become bogged down in a quest for national advantage that

undermines development and continued regional integration for the EAC.

4

The EU’s ongoing reform of electronic communication regulation for a single market for

a connected continent provides a solid background lessons for the ongoing research on

the future regulatory models for the EAC. This paper therefore assesses the potential

gains from regionalized telecommunications policy in the EAC. The paper seeks to

assist stakeholders in the EAC and Member States in designing an effective regional

regulatory process. To this end, the paper: (i) discusses how EAC regional cooperation

can overcome national limits in technical expertise, enhance the capacity of Member

States to commit to stable regulatory policy in the EAC and ultimately facilitate

infrastructure investment in the region; (ii) identifies trade-distorting regulations that

inhibit opportunities for regional telecommunication development and so are good

candidates for regional negotiations that reduce indirect market entry barriers; (iii)

discusses the EU’s ongoing regulatory reforms towards a single market for electronic

communication for a connected continent as a case study that the EAC can draw lessons

from and there after describes substantive elements of a harmonized regional

regulatory policy that can deliver performance benefits.

1.1.

Principal research question:

What is the most suitable regional response to regulation of telecommunication sector

in the East African Community (EAC) and what lessons can the EAC draw from the

experience of the European Union’s (EU) ongoing reform towards a single market for

Information Society?

1.2.

Hypothesis:

With the EAC’s common market in place since 2010, a corresponding common or

regionalized legislative and regulatory framework at the EAC level for

telecommunication sector would be a suitable vehicle to achieve regulatory

harmonization and minimize the distortions that arise from divergences in the Member

States distinct and dissimilar regulatory policies.

1.3.

Policy relevance:

The critical assessment of regional telecommunication regulation aims to provide

background for current discussions about the future of regulatory policy model in the

EAC. In particular, it provides a discussion of the EU experience in its ongoing

regulatory reform towards a single market for a connected continent. This experience

provides ideas and insights that could inform policy makers in their discussions about

the EAC approach.

5

1.4.

Methodology/approach:

This paper is prepared through desktop research. This included searches through

academic and third-party databases, regulators and government websites, and ITU and

OECD websites. The paper provides an assessment of the current legislative and

regulatory framework in each of the EAC Member States in order to demonstrate the

visible divergences there in. These include Member State national laws, regulations,

bills and policy documents relating to telecommunication sector. A discussion of the

experience of the EU’s ongoing reform towards a single EU market for Information

Society is presented as an example of a similar integrated region that the EAC can draw

lessons from.

2. LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK OF THE EAC

The East African Community (EAC)1 is the regional intergovernmental organisation of

the Republics of Kenya, Uganda, the United Republic of Tanzania, Republic of Burundi

and Republic of Rwanda (Member States) with its headquarters in Arusha, Tanzania.

The principal source of EAC law is the Treaty for the Establishment of the East African

Community (the “Treaty”).2 The Treaty was signed on 30th November 1999 and entered

into force on 7th July 2000 following its ratification by the Original three Partner States –

Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. The Republic of Rwanda and the Republic of Burundi

acceded to the EAC Treaty on 18th June 2007 and became full Members of the

Community with effect from 1st July 2007.

According to the Treaty, the main objective of the EAC is to widen and deepen the

integration process. Article 5(2)3 of the Treaty establishes the objectives to be the

formation and subsequent evolution of a Customs Union, a Common Market, a

Monetary Union and finally a Political Federation, under the overarching aim of

equitable development and economic growth amongst the Member countries.

http://www.eac.int/

The Treaty entered in force on 7th of July 2000, and was amended on 14th December 2006 and 20thAugust 2007. The

full text is to be found at http://www.eac.int/treaty/

3 Article 5(2): In pursuance of the provisions of paragraph 1 of this Article, the Partner States undertake to establish

among themselves and in accordance with the provisions of this Treaty, a Customs Union, a Common Market,

subsequently a Monetary Union and ultimately a Political Federation in order to strengthen and regulate the

industrial, commercial, infrastructural, cultural, social, political and other relations of the Partner States to the end

that there shall be accelerated, harmonious and balanced development and sustained expansion of economic

activities, the benefit of which shall be equitably shared.

1

2

6

The entry point of the integration process is the Customs Union. It has been

progressively implemented since 2004; in January 2010 the EAC became a full-fledged

Customs Union. One critical aspect of the implementation has been the establishment of

an interconnected ICT solution for a regional customs system.4

The EAC Common Market Protocol5 entered into force in July 2010, providing for the

following freedoms and rights to be progressively implemented: free movement of

goods, persons, labour, services and capital; as well as a right of establishment and

residency. The Community has since then commenced negotiations for the

establishment of the East African Monetary Union. The negotiations for the East African

Monetary Union, which commenced in 2011, and fast tracking the process towards East

African Federation all underscore the serious determination of the East African

leadership and citizens to construct a powerful and sustainable East African economic

and political bloc. The ultimate objective, to establish an East African Political

Federation, is targeted for 2016.6

The structure of the EAC promotes decision-making through consensus. Each State has

the authority to veto details of regulations formed under the Treaty. Once consensus is

reached and regulations passed, they are binding on all Partner States. Each State may

still, however, achieve regulatory goals through its own individual domestic policies.

The Treaty obliges the Partner States to plan and direct their policies and resources with

a view to creating conditions favourable to regional economic development7 and

through their appropriate national institutions to take necessary steps to harmonize all

their national laws appertaining to the Community.8

Harmonization is one of the key concepts espoused by EAC. With particular respect to

the integration of laws, Article 1269 of the Treaty and Article 4710 of the Common

Market Protocol both call for the harmonization of national legal frameworks. 11

Except for Kenya, EAC countries are using the UNCTAD ASYCUDA system for custom automation.

Article 47 provides that Partner states undertake to approximate their national laws and to harmonize their policies

and systems, for purposes of implementing the Protocol.

http://www.eac.int/advisory-opinions/cat_view/68-eac-common-market.html

6 The timelines were provided by the 13th Ordinary Summit of Heads of State in 2011.

7 Article 8(1)

8 Article 126(2)b

9 Article 126:

Scope of Co-operation

1. In order to promote the achievement of the objectives of the Community as set out in Article 5 of this

Treaty, the Partner States shall take steps to harmonize their legal training and certification; and shall encourage the

standardization of the judgments of courts within the Community.

4

5

7

It should be emphasized that two different law systems are applied among the

participating countries: Kenya, The United Republic of Tanzania, and Uganda follow a

common law system, while Burundi and Rwanda both subscribe to a predominantly

civil law system.12 This has led to somewhat divergent legislative practices and

procedures between the groups of countries, and may have contributed to slowing

down the process of harmonization efforts in the region.

The EAC has institutional frameworks at the Community level that includes the

following:

1. Summit which consists of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government whose

function is to provide overall strategy and political direction.

2. The Council consisting of the Ministers responsible for regional co-operation of each

Partner State whose function is to Coordinate and formulate policies.

3. The East African Court of Justice tasked to ensure adherence to law in the

interpretation and application of and compliance with the EAC Treaty. The Court has

jurisdiction over the interpretation and application of the Treaty and may have other

original, appellate, human rights or other jurisdiction upon conclusion of a protocol to

realize such extended jurisdiction.

4. The East African Legislative Assembly tasked with the Community legislative

powers, any legislative decision by the assembly which is gazetted by Summit will

supersede and take precedence over any other related national law.

2. For purposes of paragraph 1 of this Article, the Partner States shall through their appropriate national

institutions take all necessary steps to:

(a) establish a common syllabus for the training of lawyers and a common standard to be attained in

examinations in order to qualify and to be licensed to practice as an advocate in their respective

superior courts;

(b) harmonize all their national laws appertaining to the Community; and

(c) Revive the publication of the East African Law Reports or publish similar law reports and such law journals as

will promote the exchange of legal and judicial knowledge and enhance the approximation and harmonization of

legal learning and the standardization of judgments of courts within the Community.

3. For purposes of paragraph 1 of this Article, the Partner States may take such other additional steps as the Council

may determine.

10 Article 47: Approximation and Harmonization of Policies, Laws and Systems

1. The Partner States undertake to approximate their national laws and to harmonize their policies and systems, for

purposes of implementing this Protocol.

2. The Council shall issue directives for purposes of implementing this Article.

11 The Sub-Committee on the Approximation of Laws in the EAC Context

12 Membership of the EAC is shifting Rwanda and Burundi towards a common law approach.

8

5. The Secretariat headed by an appointed Secretary General.13

The EAC’s aspiration and goal is to use regional integration to promote peace, stimulate

economic growth, achieve solidarity for its peoples, and strengthen its international

profile/stature. The EAC is using regional integration as a vehicle for promoting peace,

in order to enhance the prospects for positive economic results. In short, the EAC is

focussed on making the East Africa’s economies more mutually interdependent among

its constituent Member States. To this end, the EAC’s aims and objectives include the

following:

-

establishing a Customs Union, a Common Market,

-

subsequently a Monetary Union and ultimately a Political Federation in order to

strengthen and regulate the industrial, commercial, infrastructural, cultural,

social, and political and other relations of the Partner States.

-

Accelerated, harmonious and balanced development and sustained expansion of

economic activities, the benefit of which is equitably shared.14

Against this background, creation of an enabling legal and regulatory environment has

been identified as a critical factor for the effective implementation of e-government and

e-commerce strategies at national and regional levels. To achieve operational efficiency

of such strategies, strong back up support is needed in terms of legislation and

regulation.

In view of the foregoing, policies and regulatory frameworks of most sectors have been

aligned to this objective. Those that have harmonised policies and regulatory

frameworks include fisheries, transport, higher education and finance. They have

regulatory frameworks and institutions at the EAC level unlike the telecommunication

sector.15

2.1.

ICT developments in the EAC

There are two key areas that have been particularly important for the economic and

regulatory environments; they include the improved fibre-optic links between the

region and the rest of the world and the expansion of mobile telephony and related

Article 9 of the Treaty establishing the East African Community( hereinafter the EAC Treaty)

See Part 1 of the Treaty establishing the European Union and Chapter 2 of the treaty establishing the EAC

15 For instance, Lake Victoria Fisheries Organization, East African Community Civil Aviation Safety and Security

Oversight Agency (CASSOA), The Inter-University Council for East Africa (IUCEA) and The East African

Development Bank.

13

14

9

services, notably mobile money.16 In July 2009, the first under-sea fibre optic cable

network, SEACOM,17 reached Kenya, the United Republic of Tanzania and Uganda. It

was soon thereafter connected with Rwanda.18 This marked the beginning of an era of

radically faster and cheaper Internet use in the EAC.

In 2010, the second submarine fibre optic cable system, EASSy became operational

along the East and South African coasts to service voice, data, video and Internet needs

of the region.19 It links South Africa with Sudan, with landing points in Mozambique,

Madagascar, the Comoros, the United Republic of Tanzania, Kenya, Somalia, and the

Republic of Djibouti. This made it more economical to connect the eastern and southern

coast of Africa with high-speed global telecommunications network. Average mobile

penetration in the EAC had reached 40 subscriptions per 100 inhabitants in 2010, with

the highest level noted in Kenya (61) and the lowest in Burundi (14)20

3. ASSESSMENT

OF

THE EAC TELECOMMUNICATION

POLICIES,

REGULATORY

AND

INSTITUTIONAL

FRAMEWORKS

One of the corner stones of the EAC’s integration process has been to create a single

market, where the trade is free across the EAC and based on the theory of comparative

advantages. Harmonization of national telecommunications regulatory frameworks in

the EAC Member States to reflect the common EAC framework should be linked to this

free trade thought. The harmonization of regulatory frameworks can be seen as a main

mechanism to eliminate unfair differences in regulatory regimes, because its purpose is

to reduce the differences in law and politics of the Member States jurisdictions. The

following sub-sections discuss the current status quo with regard to telecommunication

policies, legislative and regulatory settings in order to demonstrate the divergences

existing thereof.

See UNCTAD Report, Mobile Money for Business Development in the East African Community:

A Comparative Study of Existing Platforms and Regulations, June 2012 (UNCTAD/DTL/STICT/2012/2,

available at http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/dtlstict2012d2_en.pdf

17 http://www.seacom.mu/

18 Daily Nation newspaper on the web, 23rd July 2009. The cable covers some 17,000 kilometres.

19 http://www.eassy.org/index-2.html. The cable covers some 10,000 kilometres.

20 Source: UNCTAD, based on ITU World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators, 2011

16

10

3.1.

Divergences in telecommunications policy frameworks

The EAC Member States have in the past discussed plans for regional ICT policy

harmonisation. However, the process of telecommunications policy harmonisation has

been retarded due to a sentiment among Member states that a harmonised

telecommunications policy framework would have favoured Kenya, the leading

country in the region. Since telecommunications markets in the EAC were amongst the

earliest in Africa to open to competition, and since the EAC markets have been

historically integrated, the EAC Member States are still in the process of determining if

and how a single regulation policy can be applied uniformly.21

Despite attempts by the EAC Member States to harmonise ICT policy and regulatory

frameworks, there is still a high degree of heterogeneity among the Member States

national ICT Policy and regulatory frameworks in terms of advancement in the

harmonisation process. Some of the challenges facing the process of ICT policy and

regulatory harmonisation include the following:

existence of multiple national ICT policy and programme initiatives, some of

which are often in competition with each other;

very little ownership of EAC regional ICT policy and regulatory initiatives from

the Member States governments;

National organisations’ and institutions’ lack of institutional mechanisms to

ensure compliance with model policies and frameworks as well as to monitor

and evaluate the implementation. EAC Member States are sovereign states with

no obligations to adopt and adjust national ICT policy and regulatory

frameworks to the policy guidelines issued by EAC regional bodies; and

Different stages of economic, political and social development make it difficult

for Member States to have common priorities and therefore to adopt common

models or frameworks.22

Although resources have been put into establishing and supporting structures for the

EAC regional integration of markets and harmonisation of ICT policies, there has been

limited success in implementing harmonisation frameworks to date.

IT news Africa (2010). East African States discuss ICT policy harmonization, available from

http://www.itnewsafrica.com/?p=795.

22 Waema, T. M. (2005). In Etta, F.E. and Elder, L. (eds.), A Brief History of the Development of ICT Policy in Kenya.

At the Crossroads: ICT Policy Making in East Africa, (pp. 25-43). Nairobi, Kenya: East African Educational Publishers

Ltd.

21

11

Therefore, each of the Member States has its own distinct and dissimilar National ICT

policy. Perhaps the point of convergence stops only at the fact that today all the five

Member States have approved National ICT Policies in place. The following table gives

an overview of the National ICT policy at the Member States level as the basis for the

current regulatory frameworks.

Table of initial classification of ICT policies:

EAC Member National ICT National ICT National ICT Autonomous

State

Policy

Development

Development

Regulatory

Plan

Agency

Agency

BURUNDI

-1996:

Beginning of

process

for

restructuring

the Telecoms

sector,

publication of

sectoral policy.

-Law

governing ICT

sector

was

promulgated

Sept 1997.

- Separation of

Posts

and

Telecoms 1997.

KENYA

National ICT

Policy exists

since 2005 and

has

been

reviewed on a

number

of

occasions

e-Strategies

being prepared

A Directorate

of ICT was

created in 2006.

2002-2004

It is charged

(National

with

the

Strategy

for implementation

development of of ICT plans

ICT

Action and strategies

Plan).

- A Regulatory

Authority:

ARCT

(Telecoms

Regulatory

and

Control

Agency), was

set up late

Sept 1997.

Implementation

of

plans,

programmes

and projects is

being studied.

The

Regulatory

Agency is not

independent.

It is under the

control of the

Government,

although

Burundi

liberalised its

international

Gateway

Plan exists with Kenya

a

special Authority

Bureau in the

Office of the

President, and

a Ministry in

charge

of

implementing

the

National

Policy.

12

ICT CCK

UGANDA

National ICT

Policy exists

since 2006 and

was approved

by

the

Government

and

Parliament.

There is an

Implementation

Plan with two

components:

infrastructure

and

RWANDA

National ICT

Policy exists

since 2000 and

was approved

by

the

Government

and

Parliament.

Plan exists and RITA

is known as the

NICI

PLAN,

with

various

projects

and

programmes.

TANZANIA

It exists since Plan exists, but Non existent

2005 and was not very well

approved by developed

the

Government

and

Parliament

3.2.

National

Authority

Uganda.

(NITA-U).

IT UCC

-

e-Gov.

RURA

TCRA

Divergences in institutional arrangement

As shown in the above table, EAC Member States have various regulatory agencies and

regulatory institutions. They fall under the various ministries responsible for ICTs

and/or Telecommunications. For instance, in the case of Uganda, it is the Ministry of

ICT; in the case of Kenya, it is the Ministry of Information and Communications; while

in Tanzania, it is the Ministry of Infrastructure Development (with a Deputy Minister in

charge of all communications matters and sectors), in Burundi, the jurisdiction lies with

the Burundian Ministry of Defence. In nearly all the cases, there is also a strong ICT

Unit within the Ministry of Finance, sometimes referred also to as the Government

Computer Centre/Services, for historical reasons. In the case of Kenya, there is also the

e-Government Directorate within the Office of the President. For its part, in Uganda,

there is also a newly established National Information Technology Authority (NITA),

and Rwanda’s RITA. In Kenya, there have also been proposals to have ICT Units,

headed by a senior officer preferably at Director Level (like in Rwanda) in some, if not

13

all Ministries and public agencies. In Tanzania, there exists the office of National ICT

Coordinator. From the foregoing, it is evident that the ICT responsibilities are

distributed across different arms of the government, with little, if any, coordination,

with negative consequences including lack of clarity. Further ARCT of Burundi is not

an independent regulatory authority as it is placed under the jurisdiction of the

Burundian Ministry of Defence. All deliverance of licences are studied by the technical

personnel of the ARCT , then by its board of administration, followed by the approval

of the Ministry of transports and communications and last of all by the national

Ministry of Defence.

3.3.

Divergences in regulatory frameworks

Apart from the policies, regulation is equally non-uniform. Save for the fact that all the

Member States now have functional regulators, there is little beyond that which is

uniform. The focus for individual regulators also seems to differ, in the absence of a

concerted effort to harmonize the regulatory frameworks. The following are examples

of the divergences:

Licensing: Tanzania pioneered the converged licensing, supporting triple-play, i.e.

telecommunication, IT and broadcasting.23] In Uganda, the emphasis is on infrastructure

licensing [24], the objective is to open infrastructure to full competition. Kenya, on the

other hand, is in the process of shifting its licensing regime to a unified licensing

framework and market structure.[25] However, the focus has been at the service level,

with some of the segments being: international gateway, mobile communication, data

operator’s license, ISP, etc.[26] Rwanda’s regulator issues individual and standard

telecommunication while Burundi issues only one type of licence, the commercial

services licence which corresponds to a basic telecommunication licence. The award

criteria for licences and the ultimate responsibilities differ in each of EAC Member

States. There are also different local equity ownership requirements for license-holders,

ranging from zero local equity ownership in Uganda to a 35% requirement in Tanzania.

Further, relevant ministries and regulators have different levels of responsibility for

licensing regulation.

Key

Legal

and

Regulatory

Findings:

Available

at:

http://www.eac.int/infrastructure/index.php?option=com_docman&Itemid=146

[24] As opposed to “service licensing,” An applicant can be granted both or either license.

[25] See ‘Implementation of a Unified Licensing Framework and New Market Structure’ published by the CCK in May

2008

[26] See footnote 23 above.

[23]

14

Regulation of tariffs: various national tariffs regulatory frameworks have various

competing issues. Some Member States’ regulatory frameworks lean towards selfregulation while others provide for strict regulation by the national regulators in the

five Member States. Tanzania, Uganda and Rwanda to some extent seem to lean toward

self-regulation whereas Kenya and Burundi take the opposite approach of strict

regulation.

From the foregoing therefore, it is evident that just as there are discrepancies in policies,

so are they regulation. Currently, there does not seem to be any major effort to

harmonize the respective regulatory frameworks. Perhaps the two areas where there is

most uniformity are firstly with interconnection and sharing of facilities where most

national legislations refer to the principle of non-discrimination. Secondly, the fact that

Member States have provisions for universal service access.

3.4.

Convergence of the ICT sector in the EAC

EAC’s ICT industry, as a whole, is undergoing a potentially disruptive phase of

development. This is because there have been extensive technological changes in its

structure in recent years. These changes are the driving force behind the emergence of

convergence. Generally, the term convergence has been used to describe almost any

trend representing the ever closer contact between the telecommunications, IT and

broadcasting industry. The term is most commonly expressed as:

· The ability of different network platforms to carry essentially similar kinds of services,

or

· The coming together of consumer devices such as the telephone, television and

personal computer. [27]

It occurs when multiple products come together to form one product with the

advantages of all of them – e.g. your computer as purveyor of voice as well as text and

graphics; cell phones that provide text and graphics as well as voice. This is otherwise

referred to as technological convergence. [28] Convergence has seen major changes in the

market structure including the following:

The European Commission’s Green Paper on the convergence of the telecommunications, media and information

technology sectors and the implications for regulation, COM (97) 623, Brussels, December 1997.

[28]European Commission, Green Paper on the Convergence of the Telecommunications, Media and Information

Technology Sectors, and the Implications for Regulation. Towards an Information Society Approach. COM (97) 623,

Brussels:

European

Commission,

1997,

(www

document)

URL

http://www.ictregulationtoolkit.org/en/Publication.1500.html]

[27]

15

Entrance of new market services providers especially in the mobile market

providing services in most Member States:

New services can now be transmitted over various networks. For instance,

telecommunication companies are doing content provision. As a result,

traditional telecommunication companies are directly competing with

broadcasting companies and the newly emerging IT providers. Telkom Kenya is

currently providing new services such as internet hosting, mobile services, VoIP

and other multimedia services. [29] Others are Uganda Telecom, [30] Tanzania

Telecommunication Company Limited [31] and Rwanda Tel. [32] Some IT

companies such as Swift Global Kenya Limited, [33] UUNet Kenya, [34] Access

Kenya, [35] Africa Online Uganda Limited, [36] and Africa Online Tanzania [37] etc.

are not only providing internet services but are also providing

telecommunication services. New promising applications have emerged such as

mobile-banking. For instance, there is M-PESA system by the Kenyan mobile

operator Safaricom. [38] Towards the end of 2013, M-PESA had around 17.5

million subscribers. [39] Zap Mobile Banking was launched in February 2009 by

Zain. [40]

Regional mergers and acquisitions in the ICT sector in the EAC: For instance,

South African’s MTN recently acquired a 60% stake of UUNet; it was therefore

re-branded from UUNet to MTN Business Kenya. Access Kenya and Kenya Data

Networks have absorbed much of UUNet’s corporate business since 2008.41

Uganda’s InfoMail (IMUL) merged with the country’s second ISP, Starcom, to

form Infocom. [42] Libya’s Lap Green Networks acquired Rwanda's Rwandatel. It

See: http://www.telkom.co.ke/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=60&Itemid=95

See: http://www.utl.co.ug/

[31] See: http://www.ttcl.co.tz/

[32] See: http://www.rwandatel.rw/

[33] http://www.swiftglobal.co.ke/#

[34] http://www.ics.uunet.co.ke/index.php?option=com_frontpage&Itemid=1

[35] http://www.accesskenya.com/inner.asp?cat=prods

[36] http://www.africaonline.com/countries/ug/

[37] http://www.africaonline.com/countries/tz/

[38] See http://www.safaricom.co.ke/

[39] See http://wirelessfederation.com/news/15801-m-pesa-still-not-profitable-despite-high-growthrate-safaricomceo/ for a recent update on M-PESA figures.

[40] See: http://www.ke.zain.com/opco/#?lang=en

41

See

report

available

at:

http://www.standardmedia.co.ke/InsidePage.php?id=2000025563&cid=4&ttl=Mergers,%20acquisitions%20drive%2

0mega%20deals

[42] See: An African Pioneer Comes of Age: Evolution of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) in

Uganda

[29]

[30]

16

also owns a majority stake in Uganda Telecom (UTL). [43] Convergence Wireless

Networks (Convergence Wireless) acquired a 35% stake in WIA Company

Limited (WIA), of Tanzania in 16 November 2009. [44]

Expansion of the ICT industry to the EAC regional level: Most service providers

are currently providing services in the EAC regionally as opposed to individual

Member States. This is due to the mergers, acquisitions and continuous

expansion of new services to other sectors.

3.5.

Implication of the inconsistencies to regulation

Inconsistencies in regulation resulting from traditional separation

As the European Commission Green paper on convergence (1997) [45] identified, some

converging services are facing a regulatory vacuum. Others tend to fall under the

jurisdiction of two or more agencies, which leads to jurisdictional conflicts once they

start issuing their own rules. New services such as mobile-banking by the M-PESA,[46]

or Zap Mobile Banking,[47] have in the past caused major controversy with the bank

fraternity.[48] The banking industry’s concern has been that the mobile-banking

operators are enjoying privileges similar to those extended to banking institutions

despite not being covered by the same regulatory regime. Debate has been rife on who

should regulate the mobile-banking operators, whether it should be the central banks

and therefore regulated under the Banking Acts or the Communication Acts.

Fundamentally, the mobile operations are guided by the Communications

Commissions. Others include broadcasting over the internet. It is not clear if it should

be regulated as broadcasting or not regulated at all because they are computer based.

Inconsistencies also arise when pre-convergence classifications, such as cable and

See: http://www.cellular-news.com/story/26685.php

http://us-cdn.creamermedia.co.za/assets/articles/attachments/24554_convergence_partners__wia_invests_in_tanzania_-_16_nov_09.pdf

[45] European Commission (1997).Green paper on the convergence of the telecommunications, media and information

technology sectors, and the implications for regulation towards an information society approach Brussels: European

Commission. Accessed April 7, 2003: http://europa.eu.int/scadplus/leg/en/lvb/124165.htm.

[46] See http://www.safaricom.co.ke/

[47] See: http://www.ke.zain.com/opco/#?lang=en

[48] This according to a report by the Bankers Association in The East African (Nairobi) 12 October 2008 posted to the

web 13 October 2008

[43]

[44]

17

common carrier regulation, lead to similar services with differing regulatory

treatments.[49]

Regulatory arbitrage

As stated above, new services sometimes face more than one regulatory regime in the

various Member States. Not only are there multiple regulatory bodies, but also

conflicting regulations and licensing authorities. As a result, the regional market players

have tended to select the regulatory frameworks in the various Member States that

advance their interest the most (otherwise referred to as forum shopping). This trend

has been made even easier with the establishment of the EAC Common Market

Uncertainty

Due to rapidly changing technology, regulators tend to issue rules for the problems

faced today, these causes problems when new technologies become available. Because

of this continuous innovation, regulators need to find regulatory frameworks that allow

them to better cope with uncertainty.

4. THE EXPERIENCE OF THE EUROPEAN UNION (EU)

4.1. Motivation of the EU as a case study

The EU’s converged legislative framework is often considered a best practice model.

The ITU considers the EU’s Electronic communication regulatory framework (the

ECRF) to be the ‘paradigm legislation aimed at addressing convergence and its

challenges’.50 Commentators have called for the application of the EU model in

Australia51 and the US.52 The EU’s the ECRF came into force in July 2003 and forms the

basis for all national telecommunications laws in EU member states. Since 2003, further

changes have been made to the EU’s regulatory framework. In 2009, a

telecommunications reform package was passed that makes a number of changes to the

Garcia-Murillo, M. & MacInnes, I. (2001). FCC organizational structure and regulatory convergence.

Telecommunications Policy, 25:6, 431452

50 ITU/InfoDev, ICT Regulation Toolkit, Module 6 ‘Legal and Institutional Framework’, Chapter 4 ‘Impact of

Convergence’, section 4.5 ‘Case Studies of Converged Legislation’.

51 See Niloufer Selvadurai, ‘The Creation of the Australian Communications and Media Authority and the next

necessary step forward’, 26 Adelaide Law Review (2005) 271 and ‘Regulating for the future - accommodating the effects

of convergence’, 13 Trade Practices Law Journal 20.

52 See Frieden, Rob, ‘Adjusting the Horizontal and Vertical in Telecommunications Regulation: A Comparison of the

Traditional and a New Layered Approach’, 55(2) Federal Communications Law Journal (2003) 208.

[49]

18

ECRF.53 It establishes a new regulatory agency, the Body of European Regulators for

Electronic Communications (BEREC), to ensure a consistent and coordinated approach

to regulation. The EU has therefore considerable experience with the opportunities and

drawbacks of particular regulatory scenarios.

The EU framework for the ICT sector is built on concepts and principles such as:

technology neutrality, the shift from vertical to horizontal regulation, the expansion of

the definition of telecommunications networks and services to cover all ECNS and

graduated regulation (as a possible answer to differentiated regulatory needs).

Further, it focuses on regulatory

principles

such as transparency, flexibility,

regional harmonisation, proportionality and legal certainty.54 EAC should consider a

focus on these concepts and principles in its regional reforms.

The focus is on these regulatory concepts and/ or principles since these are generally

recognised as the basic regulatory concepts and principles underpinning

reforms of ICT regulatory frameworks worldwide.55 They are therefore accepted as

effective and can work in any context irrespective of the geopolitical, social or

cultural borders. The essence is to contextualize these basic regulatory concepts and

principles into the local cultural, social-economic, and political conditions of the EAC.

These make them concise, workable, and effective and fit for the EAC circumstances.

Further motivation for the EU as a case study is that the Institutional frameworks of

both the EU and the EAC are similar at first sight just like their powers under the

respective treaties establishing them. The EU's institutional framework includes the

EU Parliament, the Council, the Commission and the Court of justice and Court

of First Instance.56 The EAC's Summit is comparable to the EU's European Council,

because both are their respective Union’s supreme organ. Like the European Council,

whose presidency is rotated every six months among its constituent member countries,

the EAC's Summit is rotated annually among the Partner States. Key institutions of the

EAC and the EU that share similar names are the Commission, the Court of Justice, and

the Parliament.

‘Agreement on EU Telecoms Reform paces way for stronger consumer rights, an open internet, a single European

telecoms market and high-speed internet connections for all citizens’, press release, 5 November 2009,

http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=MEMO/09/491.

54

Current

legislation

available

at:

http:/Iec.europa.eu/information_society/policy

Iecomm/1ibrary/legislation/index_en.htm

55 Ilse Marthe van der Haar 2008: The principle of Network Technology Neutrality within the framework of EC

Network regulation, Part 1, Chapter 2

56 Article 7 of the Treaty establishing the European Union (hereinafter the TFEU).

53

19

Another area of similarities is with regard to their goals. Although they arrived at their

respective goals from different experiences, the aspirations are similar. Both

Communities, for example, hope to use regional integration to promote peace, stimulate

economic growth, achieve solidarity for their peoples, and strengthen their international

profile/ stature. These are provided for in Article 2 of the TFEU and chapter 2 of the

EAC Treaty.

The principle of direct applicability of community law is similar in both the EU and the

EAC. The treaties for both Communities provide for direct applicability of community

law.57 The EC Treaty, Article 249 provides that 'a regulation shall have general

application. It shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member

States.' An almost identical provision is contained in Article 8 of the EAC treaty. Both

Communities' Regulations are also subject to direct effect and immediate applicability.

They are incapable of being conditional. As provided for under Article 249 of the EC

Treaty, Communities' Decisions "are binding in their entirety on the party to whom they

are addressed”. Both Communities' directives could be directly effective insofar as the

provisions define rights which individuals are able to assert against the State."58

Member states of the EAC have enacted legislation giving 'the force of law' to 'the

provisions of any Act of the Community ... from the date of the publication of the Act

in the Gazette'.59 The EAC Treaty provides for the principle of supremacy of the laws of

the community.60 This ensures that conflicts between community law and national law

are resolved in favour of the former. This defines the place of community law in

national legal systems.

This principle of direct applicability allows both Communities' laws to become part of

national legal systems without intervening national measures which aim at

transforming the community law into a national one i.e. both Communities' laws do

not need measures such as parliamentary resolution, an act of parliament, or an

executive act such as cabinet approval.

See EC Treaty, Article 249, and EAC Treaty, Article 8

See Grad v Finanzamt Traunstein, (Case 9/70) [1970] ECR 825

59 See for instance Kenya: Treaty for the Establishment of East African Community Act 2000, Article 8(1); Uganda:

East African Community Act 2002; and Tanzania: Treaty for the Establishment of East African Community Act 2001.

60 See EAC Treaty, Article 8{4).

57

58

20

4.2.

The EU’s electronic communications regulatory framework

(ECRF)

As mentioned above, the EU’s the ECRF came into force in July 2003 and forms the

basis for all national telecommunications laws in EU member states. It sets overarching

rules for the regulation of electronic communications services and networks, which

member states are required to transpose into domestic law. The UK, Finland and the

other Nordic states were the first to implement changes transposing the 2003 EU

regulatory framework to domestic legislation. The European Commission (EC) has

reported that all EU nations have transposed the ECRF into domestic law.

While the ECRF applies to electronic communications services and networks, it does not

apply to the content that travels over those services and networks. Content is regulated

at the national level, with broad guidance at the EU level in the form of the AudioVisual Media Services Directive (AVMS Directive). However, as the EC and

commentators have noted, there are elements of the ECRF that do impact on content.

ECRF comprises the following five directives, which apply to all communications

infrastructures and associated services:

The Framework Directive—applies to all electronic communications networks and

services, including fixed-line telephony, mobile and broadband communications,

and cable and satellite television. It establishes the structural and procedural

elements of the EU regulatory framework. These include requirements for the

establishment and remit of national regulatory authorities (NRAs) and processes for

NRAs to define relevant national competition markets and analyse whether there are

any operators with significant market power (SMP) in that market. It also sets out

rules for granting resources such as numbering.

The Authorisation Directive—harmonises and simplifies authorisation rules and

conditions throughout the EU, replacing individual licences with a general

authorisation scheme.

The Access Directive—applies to all forms of communications networks carrying publicly

available communications services and covers the relations between electronic

communications providers on a wholesale basis. It establishes rights and obligations

for operators and undertakings seeking interconnection and/or access to their

networks. Overall, it means that member states must ensure there are no restrictions

preventing negotiations from taking place between operators about the technical and

commercial arrangements for access and interconnection.

21

The Universal Service Directive—concerns the relationship between electronic

communications providers and end-users. It requires the provision of directory

enquiry services and directories, public payphones and access for users with

disabilities. The directive also contains provisions on universal service obligations,

such as quality of service, as well as for regulatory control of undertakings with

significant retail market power, and a number of users’ interests and rights. NRAs

may impose a number of obligations on operators with SMP—these can include

imposing ‘must carry’ obligations on the transmission of specified radio and

television broadcast channels and services, where the relevant network serves as the

primary means of access to the services for a large number of users.

The Privacy and Electronic Communications Directive—concerns the processing of personal

data relating to the delivery of communications services.

The need to respond to convergence was a significant driver for the enactment of the

ECRF. The ECRF also responded to an urgent concern within the EU to harmonise

licence/authorisations conditions; these varied across the EU from onerous (for

example, France, Belgium) to light (Sweden, Denmark, Finland).61 As the EC has stated,

the ECRF aimed ‘to provide a coherent, reliable and flexible approach to the regulation

of electronic communication networks and services in fast moving markets’ and ‘to

provide a lighter regulatory touch where markets have become more competitive yet

ensure that a minimum of services are available to all users at an affordable price and

that the basic rights of consumers continue to be protected.’62

Since 2003, further changes have been made to the EU’s regulatory framework. In 2009,

a telecommunications reform package was passed that makes a number of changes to

the ECRF.63 It establishes a new regulatory agency, the Body of European Regulators for

Electronic Communications (BEREC), to ensure a consistent and coordinated approach

to regulation.64 While the enactment of the ECRF in 2003 represented significant change,

changes are continuing, and the framework continues to evolve. There are currently

ongoing discussions on the EC regulatory proposal to complete the telecoms single

Humphreys and Simpson, Globalization, Convergence and European Telecommunications Regulation, p. 99.

‘New

Regulatory

Framework’,

European

Commission

website

at

http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/topics/telecoms/regulatory/new_rf/text_en.htm

63 ‘Agreement on EU Telecoms Reform paces way for stronger consumer rights, an open internet, a single European

telecoms market and high-speed internet connections for all citizens’, press release, 5 November 2009,

http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=MEMO/09/491.

64 Detailed overview available at: Laurent Garzaniti: Telecommunications, Broadcasting and the Internet

EU Competition Law and Regulation

61

62

22

market and deliver a Connected Continent.65 The overarching aim is to build a

connected, competitive continent. The proposal includes the following:

Simplification and reduction of regulation for companies

More coordination of spectrum allocation – so that we see more wireless

broadband, more 4G, and the emergence of pan-EU mobile companies with

integrated networks

Standardised wholesale products: encourages more competition between more

companies

Protection of Open internet: guarantees for net neutrality, innovation and

consumer rights.

Pushing roaming premiums out of the market: a carrot and stick approach to say

goodbye to roaming premiums by 2016 or earlier.

Consumer protection: plain language contracts, with more comparable

information, and greater rights to switch provider or contract.

4.3.

Lessons from the experience of the EU

The lessons learned from the EU include inter alia that the regulatory framework

represents a bold and innovative response to the challenges of convergence and

harmonization. The following is a summary of general lessons drawn from the

assessment of the ECRF:

1. Ensure technological neutrality of all laws, and envisage introducing a

mandatory legislative "neutrality test".

The experience is that the ICT sector evolves too quickly for legislators to catch up.

Laws that are drafted with particular technologies in mind may therefore present a

legal hurdle for new technologies.

2. Adopt converged legal rules.

Due to the increasing convergence of the ICT sector, it is no longer appropriate to

maintain separate laws for the distinct traditional sector. Such separation undermines

the core value of the predictability of the legal rules.

3. Envisage maximum harmonization when drafting new regulatory framework

that impact the information society.

65

Overview available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-13-779_en.htm

23

While the use of uniform and clear criteria for determining the applicable law is

recommended, a certain level of complexity will remain, due to the inherently

borderless nature of the information society. Maximum harmonization can significantly

help to reduce the importance of the question which national law applies.

4. Amend the current EAC legal instruments on jurisdiction and applicable law to

include criteria that are suitable for today's complex information society

services.

These legal instruments currently mainly rely on geographical criteria (such as the place

of delivery or the country where the damage occurs), which are unsuitable for

information society services for which the geographical location is irrelevant or difficult

to determine.

With regard to the ongoing reform on course to a single market for electronic

communication to achieve a connected continent proposal:

The proposal complements the existing legislation that would make a reality of two key

EU Treaty principles: the freedom to provide and to consumer (digital) services

wherever one is in the EU. The proposal does this by pushing the telecoms sector fully

into the internet age and removing bottlenecks and barriers so Europe’s 28 national

telecoms markets become a single market (building on 2009 ECRF, and more than 26

years of work to create that single market).66

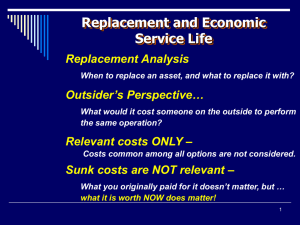

The following table is a summary of the main elements of the EC proposal that consist

essential lessons for the EAC of how the EU intends to provide solutions to the

persisting problems:

Problem

Solution

Operators wanting to go cross-border One-stop shop: operators operating in

face red tape (both hurdles and burdens) more than one Member State will benefit

from a single EU authorization requiring

only

one

notification,

thereby

establishing one reference regulator

(NRA)

for

authorization

issues

(including withdrawal/suspension of

Proposal available at: http://ec.europa.eu/digital-agenda/en/connected-continent-single-telecom-market-growthjobs

66

24

the authorization)

Inconsistent obligations for operators

operating in more than one Member

State

One-stop shop for authorization

will provide consistency for

companies

Commission will have the power

to require national regulators to

withdraw

draft

regulatory

proposals which are incompatible

with EU law (thus prevent

regulatory inconsistency)

Decisions of national regulators

must promote investment and

consider

all

competitive

constraints (including from OTTs)

– which will be crucial for

establishing a level playing field

with OTTs

The criteria that the Commission

and national regulators apply for

selecting markets that should or

should not be regulated are

strengthened by the inclusion of

the well-established “3 criteria”

test in EU law. This prevents overregulation of competitive markets.

Full harmonization of consumer

protection rules will remove the

need for customizing services for

every

territory,

and

give

consumers extra certainty

Inconsistent fixed wholesale access for Standardized fixed access products

service providers operating in more than (Virtual Unbundled Local Access, bit

stream access and Ethernet leased lines)

one Member State

and Assured Quality Services for

European electronic communications

providers) will facilitate market entry

25

and provision of cross-border services

Uncoordinated

spectrum

access

conditions for mobile operators make it

more difficult to plan long-term

investments, operate cross-border and

eventually gain scale. Today vital

wireless broadband spectrum is released

at different moments in the EU, subject

to different timing considerations and

under different conditions

Common regulatory principles for

spectrum

authorization

procedures

for

wireless

broadband to support economies

of scale

Common best practice criteria for

defining the availability and

conditions of spectrum for

wireless broadband

Harmonization of timing and

duration of spectrum assignments

for wireless broadband

Commission's power to organize

peer review among Member

States and to review national

assignment procedures

No EU-wide consumer rules (hurts and

Full harmonization of consumer

protection (not only minimums or

confuses both consumer and operator)

options as in current Universal

Service Directive)

End misleading advertising of

Internet speeds (you will get what

you pay for).

New

rights

to

transparent

information & easy contract

switching (both telecoms + net)

Roaming is an anomaly in a Single Strong incentives for operators to

provide roaming at domestic price levels

Market

by no later than 2016 throughout the EU.

Charges for incoming roaming calls will

end in July 2014.

26

5. RECOMMENDATIONS

This section demonstrates the potential gains from regionalized regulatory frameworks

in the EAC as inspired by the EU. To this end, the section:

I.

II.

discusses how EAC’s regional cooperation can overcome national limits in

technical expertise, enhance the capacity of nations credibly to commit to stable

regulatory policy, and ultimately facilitate infrastructure investment in the

region;

Describes substantive elements of a harmonized regional regulatory policy that

can deliver immediate performance benefits.

5.1.

Regionalizing EAC regulatory framework

Regionalized reform is attractive because it contributes to the efficiency goals of policy

reform while sidestepping some of the political obstacles to effective reform.

Infrastructure reform, when implemented in each Member State independently, can

become bogged down in a quest for national advantage that undermines development

for everyone. A useful analogy is the process of setting tariffs. When each Member State

independently sets each tariff separately, the outcome is likely to be tariffs that are

higher than the tariffs that would be negotiated bilaterally as part of a comprehensive

trade agreement. The reason is that debating tariffs one product at a time maximizes the

effect of the tendency for organized interests with a direct stake in a policy to be unduly

influential. Another example is termination charges for international calls, in which

many Member States set exorbitant rates for the purposes of implicitly taxing foreigners

to pay for part of the domestic network. Of course, if all Member States follow the

policy, the primary effect is to suppress regional communications, along with

opportunities for further economic integration that require inexpensive

communications.

Regionalization of legislative and regulatory policy has important political benefits.

Within a single Member State, infrastructure reform, especially when debated one issue

at a time, is often blocked by well-organized interest groups. But if reform becomes part

of a broader EAC regional policy that covers a range of issues, all stakeholders will

likely participate—making it more difficult for a single group to block it. Political

interference is more difficult and costly when regulatory policy is part of a regional

agreement, or when the regulatory body is a multinational agency.

27

Some Member States like Burundi that lack formal institutions and technical expertise

have still another reason to regionalize regulatory reform. A pragmatic response to

limited national regulatory capacity is to increase policy and regulatory coordination

and cooperation—and ultimately to create regional (multinational) regulatory

authorities. These bodies also can be a means for disseminating information and

expertise from other Member State that are further along the reform path to those that

are just beginning their reform process.

Moreover, regional regulatory cooperation and the eventual creation of a regional

regulatory authority are more feasible in the EAC since the Community has already

made substantial progress on regional economic integration including the establishment

of the common market.

Obtaining consensus from all governments in the EAC for a regional regulator is not

easy, due to different attitudes, approaches and commitments to reform, as well as

concerns about national sovereignty. Effective international regulatory policy requires

considerable cooperation and trust between Member States, which can be built through

an assembly of regulators from the Member State. Consensus for a regional regulatory

body could increase as Member States reform, and the gains from regional policy

coordination and trade become more apparent.

5.2.

Harmonization of Regulatory Frameworks in EAC

5.2.1. Spectrum of Harmonization Models

Regional harmonization is not a binary variable. It entails a wide range of policy

options that lie between complete national autonomy and full integration (as

demonstrated in the figure below). At one extreme, the Member States surrender their

sovereignty on regulatory and other policy decisions to a regional regulatory authority

(RRA). At the other extreme, the national regulatory authorities (NRAs) retain full

jurisdiction over all areas of regulatory policy and decision-making, with the RRA’s role

limited to disseminating information, issuing non-binding guidelines, and acting as a

source of centralized technical expertise.

28

Source: Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (2003).

Centralized Harmonization

Under full, centralized harmonization, the RRA has the statutory authority to make

policy determinations that are binding on the Member States. Moreover the RRA has

the legal power and framework to enforce those decisions and to impose penalties in

the event of non-compliance by the member states. Thus, the RRA would have the

authority to:

Regulate end-user prices and impose quality of service obligations on all licensed

telecommunications operators in the Community, with penalties attached for

non-compliance

Regulate the terms and conditions of interconnection and access to bottleneck

telecommunications facilities, and intervene to resolve interconnection disputes

Manage and allocate all aspects of the frequency spectrum in the EAC territory

Issue licenses for all telecommunications services throughout the Community.

Pre-empt local and national rules regarding rights of way

Collect and disburse funds to support universal service and other social goals in

the telecommunications sector

Represent the community in international organizations

Under central harmonization the NRAs would have no independent policy-making

authority. Instead, their role would be limited to providing an input into the

consultative process of the RRA, supply data on national market conditions, and advice

on implementation issues.

29

The centralized harmonization model treats the entire EAC region as a single economic

space and as such it offers the greatest opportunity to exploit regional economies of

scale in the telecommunications industry. It also holds the promise of lowering the cost

of doing business in the region by reducing the administrative barriers and regulatory

costs of entry (e.g. by facilitating access to the necessary licenses and permits through

“one-stop shopping”). The creation of supra-national regulatory authority raises, on the

other hand, proper concerns about accountability and the need for checks and balances

on the powers of such authority.

Separated Jurisdiction

Under separated jurisdiction, the RRA is charged with regulating telecommunications

transactions between the member states and represent the region in international

forums while the NRAs have full regulatory authority over telecommunications

transactions and services that do not cross national boundaries.

Centralized Policy/National Implementation

Under this model, the RRA issues binding regulatory and other policy directives which

are then adopted by the member states and converted into national law. The NRAs

have the full responsibility to implement and enforce these directives. Thus, each

Member State retains its sovereignty over regulatory matters but it is obligated to

implement its national policies in accordance with the overall policy recommendations

and directives issued by the center.

In this model, the RRA acts as a policy-making body that establishes regional policy

through a consultative process. It is very similar to the one adopted by the EU where

the Commission formulates policy and issues directives that have the force of European

law. But it is the responsibility of the Member States to adopt the directives into

national laws and regulations and thus to establish and implement national regulation.

This model treats the entire EAC region as a single economic space while at the same

time it recognizes the importance of national sovereignty and the reality of significant

cross Member States differences in institutional endowments and legal structures,

traditions and processes. The practical outcome of this compromise between

maintaining national sovereignty and pursuing regional policy harmonization is likely

to be the uneven adoption and implementation by the member states of policies

developed by the regional authority. Inevitably, some member states will be slow and

reluctant to implement the RRA directives into national laws and regulations.

30

Decentralized Harmonization

Under this model, the RRA acts as a central source of technical expertise, undertakes

regional and benchmarking policy studies, facilitates information exchange, publishes

reference papers that summarize the emerging international experience on important

policy issues, and organizes regional training programs. The RRA has no regulatory

authority but it can issue non-binding regulatory and other policy guidelines. While

this model, at least in the early stages of regional integration, represents the most

realistic organizational option, it offers very little assurance that uniform and consistent

regulatory policies will be effectively implemented across the EAC. Thus, trade

distortions created by differences in regulatory efficiency among the EAC Member

States are likely to persist.

Based on that foregoing, the recommendation is to establish independent regulatory

bodies along the lines of The Body of European Regulators for Electronic

Communications (BEREC) of the EU. A regional regulatory authority could play a very

important role in reducing the regional risk of regulatory failure due to the lack of

technical and economic expertise in critical areas by: encouraging the design of effective

and practical regulatory regimes in the Member States; identifying less sophisticated

regulatory instruments that do not impose significant informational and analytical

requirements on the NRAs; undertaking benchmarking and other studies on important

areas of policy and disseminating the findings of those studies through the publication

of reference papers and technical guidelines; designing training programs for the staffs

of the NRAs.

Thus, such a body should carry out the following tasks:

Identify the substantive regulatory issues that are likely to arise in the Member

States that are implementing restructuring and privatization programs in

telecommunications (e.g. the pricing of access to bottleneck network facilities,

reducing rigidities and inefficiencies in retail tariff structures, competitively

neutral mechanisms for funding universal service mandates), and suggest

strategies for addressing these issues

Deepen the regional understanding of how to design effective and practical

regulatory mechanisms in the face of scarce technical and economic expertise

Evaluate the efficacy of the new regulatory principles that have emerged in the

last decade stipulating a preference for competition and reliance on market-like

solutions and assess their applicability to the unique circumstances of the EAC

Member States-- in particular the consequences of unstable macroeconomic

31

conditions and imperfectly developed capital markets for the pace and extent of

appropriate regulatory decontrol

Identify options for the structural reorganization of industries that reduce the

need for regulatory oversight

Develop more precise criteria distinguishing between cases where regulatory

intervention is required and those where it is not

Develop models for optimal allocation of scarce regulatory resources among

firms and sectors with different sizes, technologies, information asymmetries,

and political constraints

Identify appropriate, perhaps less sophisticated, tools of intervention better

suited to regulators in the EAC region

Identify the fundamental principles that must be articulated publicly by the

NRAs as the basis for their policy analysis and regulatory decisions—e.g.,

commitment to the financial interests of investors at the baseline level established

by the terms of privatization; reliance on the workings of the market wherever

there is or could be reasonably effective competition; weigh the cost of rules

against the benefits; allow open access to bottlenecks on terms that reflect

competitive parity; assure service quality and price levels that are consistent with

the competitive standard; provision of economically efficient signals and

incentives to final consumers, to suppliers of complementary and substitute

services, to upstream suppliers, and to investors.

There are a number of policy and regulatory safeguards that would create an enabling

regional environment for the success of the cross-border initiatives. They include the

following:

Harmonize international gateway licensing procedures to help overcome

‘artificial’ barriers within the EAC region to flows of intra-regional traffic.

EAC Intra-Regional Interconnection Service: EAC Member States need crossborder interconnection agreements between States to allow traffic flow.

International termination charges: The effect of implementing a transit service

within EAC is that traffic from an operator in one Member State can flow to

another uninhibited by tariffs or licensing barriers.

6. CONCLUSION

The paper has demonstrated that with the establishment of the common market in the

EAC in 2010, most telecommunication service providers are venturing into regional

operations. Currently, there is a lack of a regionalized regulatory framework and

32

therefore regulation remains at the Member States level. There various divergences

from the national policies, regulation to institutional settings. Therefore, market players

are faced with various dissimilar regulatory requirements in the various Member States.

The experience of the EU has been studied as an example from which the EAC should