Types of Fronts

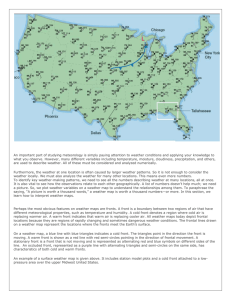

advertisement

Graphic by John Herne Warm fronts not as nice as they sound By Chad Palmer, USATODAY.com The term "warm front" sounds like something you'd like to have coming your way on a cold winter's day. Think again. A warm front is the boundary between warm and cool, or cold, air when the warm air is replacing the cold air. That sounds like what you want. However, warm fronts often bring days of inclement weather. Warm fronts often form to the east of low pressure centers, where southerly winds push warm air northward. As the warm air advances northward it rides over the cold air ahead of it, which is heavier. As the warm air rises the water vapor in it condenses into clouds that can produce rain, snow, sleet or freezing rain, often all four. (Related: Storms that bring rain, ice, and snow) The warm front symbol on a weather map marks the warm-cold boundary at the earth's surface. The circles on the red line point in the direction the warm air is moving. As you move into the cold air the warm-cold boundary is overhead. The boundary, along with clouds and precipitation, can stretch hundreds of miles over the cold air. This is why a slowmoving warm front can mean hours, if not days, of cloudy, wet weather before the warm air finally arrives. Since warm air is lighter and less dense than cold air, the cold air ahead of a warm front at the surface must retreat before warm air can move in. Sometimes, cold air is very stubborn and hard to move, which slows the warm front down and can lead to several days of wet weather. This happens often during winter along the East Coast as cold air banks up against the Appalachian Mountains. It is commonly referred to as cold air damming Source: USA TODAY research, Graphic by John Herne Cold fronts not always all that cold By Chad Palmer, USATODAY.com The term "cold front" is one of meteorology's most misused terms. Many people say "cold front" when they are really talking about the mass of cold air that moves in behind the front. (Related graphic: All about air masses). In weather, all fronts are boundaries between masses of air with different densities, usually caused by temperature differences. A cold front is a warm-cold air boundary with the colder air replacing the warmer. While a winter cold front can bring frigid air, summer cold fronts often can more accurately be called "dry" fronts. As anyone who's ever suffered through a few days of hot, humid air anywhere east of the Rockies can tell you, cold fronts are welcome visitors because they often bring air that might be only a few degrees cooler, but much less humid. The weather map symbol for a cold front is a blue line with triangles pointing the direction the cold air is moving. As a cold front moves into an area, the heavier, cool air pushes under the lighter, warm air it's replacing. The warm air cools as it rises. If the rising air is humid enough, water vapor in it will condense into clouds and maybe precipitation. In the summer, an arriving cold front can trigger thunderstorms, sometimes severe thunderstorms with large hail, dangerous winds and even tornadoes. As a cold front arrives in a particular place, the barometric pressure will fall and then rise. Winds ahead of a cold front tend to be from a southerly direction while those behind the front - in the cooler air - tend to be northerly. In fact, weather stations use the shift from a southerly to a northerly wind direction as the indication that a cold front has passed the station. USATODAY.com graphic by David Evans Occluded fronts can signal weakening of storm By Chad Palmer, USATODAY.com Often, in the later stages of a storm's life cycle, a frontal occlusion occurs. This happens when the air in the warm sector of the storm is lifted off the ground. This can happen in two ways: A cold occlusion, which occurs when the air behind the front is colder than the air ahead of the front. In this situation, the coldest air undercuts the cool air ahead of the front and the occluded front acts very similar to a cold front. A warm occlusion, which occurs when the air behind the front is warmer than the air ahead of the front. In this situation, the cool air is lighter than the coldest air ahead of the front. As a result, the cool air rises up and over the coldest air at the surface and the occluded front acts very similar to a warm front. In both types of occlusions, the occluded front has well defined vertical boundaries between the coldest air, the cool air, and the warm air. Many weather textbooks state that occluded fronts occur when the cold front catches up with and overtakes the warm front, but many scientists disagree. They say that frontal occlusions occur when storms redevelop farther back into the cold air. In most cases, storms begin to weaken after a frontal occlusion occurs. Source: USA TODAY research by Chad Palmer, Graphic by John Herne Stationary fronts prolong bad weather A cold front is the boundary between cool and warm air when the cool air is replacing the warm air. A warm front is the boundary when the warm air is winning the battle. When the pushing is a standoff, the boundary is known as a stationary front. Stationary fronts often bring several days of cloudy, wet weather that can last a week or more. Since neither the warm air nor the cold air are advancing, the stationary front weather map symbols combine both the cold front and the warm front symbols. Maps show stationary fronts with alternating triangles pointing away from the cold air and half circles pointing away from the warm air. Color maps alternate the cold front blue and warm front red. A weather map's frontal position shows where the boundary touches the Earth. The boundary can be thousands of feet above the ground a couple of hundred miles away from the surface front. If there's enough humidity in the air, clouds and precipitation will form as warm air overruns cool air along a stationary front. Sometimes, stationary fronts can stay stationary or nearly so for days. When this happens, the sky can stay gray with rain or snow. Stationary fronts are also good places for new low pressure areas to begin and grow into storms.