LESSON PLAN Title: An Island-Based History of Environmental

advertisement

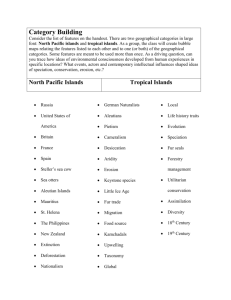

LESSON PLAN Title: An Island-Based History of Environmental Ideas: Seminal Marine Mammal Conservation Practices in the North Pacific Emily Hutcheson Quick Description of the Class Islands act as microcosms of the larger world. Environmental processes—extinction, evolution, climate change—and how human actions affect these processes, are easier to see and understand on islands. This lesson plan teaches the significance of place to the production of environmental ideas through an analysis of the Russian empire’s experience with the extinction of Steller’s sea cow and the near extinction of sea otters in the North Pacific. It employs two student-centered activities, one aimed to help prepare students for discussion and another that maps the connections between concepts. Designed to fit into a course on the history of environmental thought as it relates to plants and animals, this lesson plan emphasizes the processes of knowledge production within the context of imperialism. The disciplinary background of the lesson plan and course is a combination of history of science and environmental history. Advanced undergraduates interested in the historical basis of conservation biology would be best suited to the course. Learning Objective The primary learning objective for this lesson plan is to understand the importance of islands in the global production of ideas concerning conservation and environmental management. The underlying learning objectives involve understanding the global extinction of Steller’s Sea Cow compared to the local extinction of sea otter populations on distinct islands. In addition, students will analyze the role of empire in relation to creating scientific knowledge. Students will be able to describe what made the Russian empire unique, and how its distinctiveness allowed it to produce and incorporate a grasp on extinction in order to implement conservation measures. Complementing the content-based objectives, the lengthier activity within this lesson plan will help build the reasoning skills necessary to reconstruct complex historical chains of events. Course Plan This lesson completes the second unit of the course plan, constituting a section on islands and environmental thought. This lesson ties together how imperial projects affected island ecosystems and what people learned in the process. Specifically, it introduces a less commonly taught actor in the context of islands and empires (Russia), as well as introduces the Russian awareness of extinction—a result of their North Pacific imperial project. At the same time, this lesson will review concepts from the previous two lesson topics—islands and empire, islands and evolution. By showing a detailed history of the global extinction of Steller’s sea cow and local extinctions of sea otters on individual islands, this lesson solidifies the idea of the island as laboratory for conservation practices. Lesson Timeline: 75 minute class 20 minute of lecture 10 Participation Prep 15 minutes of lecture 30 minutes for activity: Category Building Related Reading For this lesson: The introduction and second chapter of Ryan Tucker Jones’s Empire of Extinction: Russians and the North Pacific’s Strange Beasts of the Sea, 1741–1867 (Oxford and New York.: Oxford University Press, 2014). For the previous two lessons: Grove, Richard, “Conserving Eden: The (European) East India Companies and Their Environmental Policies on St. Helena, Mauritius and in Western India, 1660 to 1854,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 35:2 (1993), pp. 318-351. Tucker, Richard P., “Unsustainable Yield: American Foresters and Tropical Timber Resources,” in Insatiable Appetite: The United States and the Ecological Degradation of the Tropical World, a selection on deforestation of the Philippines. Student-Centered Activity There will be two Student-Centered activities in this lesson, a quick one (Participation Prep-10 minutes) and a lengthier one (Category Building-30 minutes). After the first 20-minute lecture introducing the Russian imperial project in the North Pacific and the North Pacific ecosystems, the students will be given three questions, asked to choose one to answer individually (by writing it down) and asked to be ready to share (orally). The second, longer student centered activity (30 minutes) follows a 15-minute lecture block and will act as a review of concepts covered in this lesson plan as well as concepts introduced in the two previous lessons (relating to empire and evolution). The activity, drawn from Therese Huston’s Teaching What You Don’t Know, is concerned with building categories and asks students to logically group related ideas together, helping them to actively reconstruct conceptual developments from historical contingencies. Huston’s specific instructions can be found on pages 154-157 of her book.1 Similar to mind-mapping, this activity is a useful tool for the instructor to see how well the students understand the conceptual relations between ideas, places and peoples—some features will be easy for students to categorize and others may be more difficult. Huston recommends that the categorizing activity be done in small groups of two to three people, but this lesson plan has the whole class mapping the concepts together. The activity should take between 15 and 30 minutes. Thirty minutes have been allotted in this lesson for both giving instructions and working on the activity as a group. The instructor will diagram the map on the whiteboard, following input from students. This allows the instructor to set-up and steer the mapping process while the students provide input and reason through which ideas connect to different features. Therese Huston, Teaching What You Don’t Know, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), pp. 154-157. 1 Materials Needed Handout of Category Building (see end of page) PowerPoint slides with questions for Participation Prep (see end of page) Set-Up 20-minute lecture one: Covers the Russian Imperial Project in the late 18th century. 15-minute lecture two: Covers the lessons of the Russian Imperial Project in the 19th century, and how they compare to other imperial interactions with disappearing animal populations. Both of these lectures draw from Ryan Tucker Jones’ Empire of Extinction: Russians and the North Pacific’s Strange Beasts of the Sea, 1741–1867 but do not overlap exactly with the assigned reading selections. Both activities draw on ideas from previous readings (Richard Grove and Richard Tucker), as well as the assigned reading and lecture from this lesson plan. Directions for Students: Participation Prep Directions: Consider the following questions and, on a sheet of paper, write down a short answer to one of them (think of them as potential short answer questions for a test!). Use complete sentences and be prepared to share your answer with the class. You will have five minutes to prepare your thoughts and write them down. a. Compare the Aleutian Islands to Mauritius, St. Helena, The Philippines, or New Zealand (choose one). What happened to the animal populations or environment with Europeans’ arrived? Did anyone record or respond to the changes? b. What made the Russian empire unique, and how did its distinctiveness affect its consciousness of environmental change? c. Why was it difficult for people in the 18th and 19th centuries to comprehend that animals could go extinct? Directions for Students: Category Building Directions: Consider the list of features on the handout. There are two geographical categories in large font: North Pacific islands and tropical islands. As a group, the class will create bubble maps relating the features listed to each other and to one (or both) of the geographical categories. Some features are meant to be used more than once. As a driving question, can you trace how ideas of environmental consciousness developed from human experiences in specific locations? What events, actors and contemporary intellectual influences shaped ideas of extinction, speciation, conservation, erosion, etc.? Recap The marine ecosystem in the North Pacific is one of the richest on the planet. However, its species were still vulnerable to humans, and their vulnerability taught the empire of Russia that extinction occurs and is caused by humans. This novel idea is one that affected environmental thought—human culpability in changing environment conditions is much older than we imagine, yet it takes us centuries to accept it. The second activity will allow the instructor to evaluate how well the students comprehend the lesson. Take-home points: The distinctiveness of the Russian imperial project allowed it to understand the human cause of extinction Islands are microcosms for understanding environmental processes Ecosystems can be both fragile and productive Knowledge production is connected to geographic places References: Grove, Richard. “Conserving Eden: The (European) East India Companies and Their Environmental Policies on St. Helena, Mauritius and in Western India, 1660 to 1854.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 35:2 (1993). Huston, Therese. Teaching What You Don’t Know. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2009. Jones, Ryan Tucker. Empire of Extinction: Russians and the North Pacific’s Strange Beasts of the Sea, 1741–1867. Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York. 2014. Tucker, Richard P. Insatiable Appetite: The United States and the Ecological Degradation of the Tropical World. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. 2007. (Concise Revised Edition)