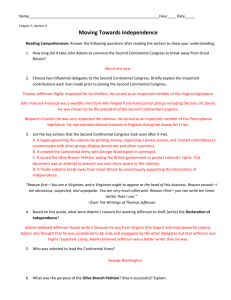

Bios of Founding Fathers - Boyd County Public Schools

John Adams (1735-1826)

John Trumbull (1756-1843)

Oil on canvas, 1793, NPG.75.52

National Portrait Gallery,

Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

John Adams was a leading advocate for the separation of the American colonies from England. A native of Braintree, Massachusetts, he received an education at

Harvard before studying law. As a young attorney in Boston, Adams saw growing political unrest in New England and throughout the colonies. He frequently fueled anti-British sentiment with newspaper editorials and other writings that defended the rights of colonial citizens against the distant authority of the British Crown. In 1774, after serving in the Massachusetts House of

Representatives, Adams was appointed a delegate to the newly formed Continental Congress.

During the next few years, Adams became deeply involved in the steady colonial march toward separation from Britain. Once the Continental Congress officially voted for independence on June

7, 1776, Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and two others were chosen to draft a manifesto declaring independence. After a lengthy debate in which Adams vigorously defended the document before his fellow delegates, Congress accepted and ratified the final version of the

Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. By denouncing the authority of the Crown, the signers of the declaration were committing a dangerous act of treason. Nevertheless, their actions, and the stirring language of the document itself, would forever change the world and its concept of liberty and equality.

Over the next decade, when he wasn't busy writing and assisting with the war effort at home,

Adams conducted official business abroad. Then, in 1785, he was named America's first ambassador to England. During these long periods away from home, Adams exchanged frequent letters with his wife, Abigail. These published letters and Adams's diary paint a delightful picture not only of John and Abigail and their family, but of their candid reactions to the historic events of the time.

In 1789, Adams received the second highest number of electoral votes in the bid for the presidency, hence he became vice president to George Washington's first presidency of the United States of

America. After serving eight years as vice president, in 1797 he succeeded Washington as president. During these years, a debate raged over the proper size and function of the federal government, and two political parties emerged to battle the issue. Adams aligned himself with the

Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, who favored a stronger central government. The opposing

Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson , were more egalitarian, and favored a sharply limited federal authority. Eventually Adams alienated members of both parties, and left the presidency in bitter disappointment. Adams retired to his Massachusetts farm and quickly regained his stature as one of this country's elder statesmen and a founder of American democracy.

However, Adams took particular pleasure in living to see his son, John Quincy Adams , elected president in 1825.

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826)

Charles Bird King (1785-1862) after Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828)

Oil on panel, 1836, NPG.92.110

National Portrait Gallery,

Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

The epitaph that Thomas Jefferson chose for his tombstone reads: "Here was buried

Thomas Jefferson, Author of the Declaration of Independence, of the statute of

Virginia for Religious Freedom, and Father of the University of Virginia." While these represent only a few of Jefferson's numerous accomplishments, they reveal much about the passions that motivated him in both his public and private life.

Americans most often recognize Jefferson as the principal author of the Declaration of

Independence. The son of a respected Virginia planter, Jefferson had access to the best education available in the American colonies. While studying law, and later as a young member of Virginia's legislature, he joined others who came to detest the tyranny of England's tight control over the

American colonies. When Jefferson was chosen to represent Virginia at the outlawed Second

Continental Congress in 1775, his personal passion and eloquence made him a natural choice to be on the committee to draft the document that would declare America's independence from the

British Crown.

To the end of his life, Jefferson was a firm believer in the natural rights of the individual. In his words, "The God who gave us life gave us liberty at the same time: the hand of force may destroy, but cannot disjoin them." One of the most significant expressions of that conviction was his authorship of Virginia's Statute for Religious Freedom, which he always considered one of his greatest accomplishments.

Jefferson once referred to his presidential terms, from 1801-1809, as a "splendid misery" and did not think enough of that chapter in his life to mention it when he wrote his own epitaph. Yet his

White House years had some significant accomplishments, not the least of which was the 1803 acquisition of the vast trans-Mississippi wilderness known as the Louisiana Purchase from France.

Despite his busy public life, Jefferson engaged in an amazing diversity of intellectual pursuits. He was an avid reader, linguist, inventor , and student of mathematics, science, agriculture, viticulture , and architecture. He was an astute observer of both the natural world and the world of people, and he recorded many of his observations in notes and letters. He loved his Virginia plantation,

Monticello, where he designed an elegant house. He ardently believed in universal education , and while he never lived to see his hope for free public schooling in Virginia realized, he could take satisfaction in the central part he had played in founding and designing the original buildings for the University of Virginia.

Benjamin Franklin

State: Pennsylvania (Born in Massachusetts)

Date of Birth: January 17, 1706

Date of Death: April 17, 1790

Schooling: Self Taught, Honorary L.L.D. Edinburgh 1759

Occupation: Inventor, Real Estate and Land Speculation, Lending and Investments,

Publisher, Retired

Biography from the National Archives : Franklin was born in 1706 at Boston. He was the tenth son of a soap and candlemaker. He received some formal education but was principally self-taught. After serving an apprenticeship to his father between the ages of 10 and 12, he went to work for his half-brother

James, a printer. In 1721 the latter founded the New England Courant, the fourth newspaper in the colonies. Benjamin secretly contributed 14 essays to it, his first published writings.

In 1723, because of dissension with his half-brother, Franklin moved to Philadelphia, where he obtained employment as a printer. He spent only a year there and then sailed to London for 2 more years. Back in

Philadelphia, he rose rapidly in the printing industry. He published The Pennsylvania Gazette (1730-48), which had been founded by another man in 1728, but his most successful literary venture was the annual

Poor Richard 's Almanac (1733-58). It won a popularity in the colonies second only to the Bible, and its fame eventually spread to Europe.

Meantime, in 1730 Franklin had taken a common-law wife, Deborah Read, who was to bear him a son and daughter, and he also apparently had children with another nameless woman out of wedlock. By 1748 he had achieved financial independence and gained recognition for his philanthropy and the stimulus he provided to such civic causes as libraries, educational institutions, and hospitals. Energetic and tireless, he also found time to pursue his interest in science, as well as to enter politics.

Franklin served as clerk (1736-51) and member (1751-64) of the colonial legislature and as deputy postmaster of Philadelphia (1737-53) and deputy postmaster general of the colonies (1753-74). In addition, he represented Pennsylvania at the Albany Congress (1754), called to unite the colonies during the French and Indian War. The congress adopted his "Plan of Union," but the colonial assemblies rejected it because it encroached on their powers.

During the years 1757-62 and 1764-75, Franklin resided in England, originally in the capacity of agent for

Pennsylvania and later for Georgia, New Jersey, and Massachusetts. During the latter period, which coincided with the growth of colonial unrest, he underwent a political metamorphosis. Until then a contented Englishman in outlook, primarily concerned with Pennsylvania provincial politics, he distrusted popular movements and saw little purpose to be served in carrying principle to extremes. Until the issue of parliamentary taxation undermined the old alliances, he led the Quaker party attack on the Anglican proprietary party and its Presbyterian frontier allies. His purpose throughout the years at London in fact had been displacement of the Penn family administration by royal authority-the conversion of the province from a proprietary to a royal colony.

It was during the Stamp Act crisis that Franklin evolved from leader of a shattered provincial party's faction to celebrated spokesman at London for American rights. Although as agent for Pennsylvania he opposed by every conceivable means the enactment of the bill in 1765, he did not at first realize the depth of colonial hostility. He regarded passage as unavoidable and preferred to submit to it while actually working for its repeal.

Franklin's nomination of a friend and political ally as stamp distributor for Pennsylvania, coupled with his apparent acceptance of the legislation, armed his proprietary opponents with explosive issues. Their

energetic exploitation of them endangered his reputation at home until reliable information was published demonstrating his unabated opposition to the act. For a time, mob resentment threatened his family and new home in Philadelphia until his tradesmen supporters rallied. Subsequently, Franklin's defense of the

American position in the House of Commons during the debates over the Stamp Act's repeal restored his prestige at home.

Franklin returned to Philadelphia in May 1775 and immediately became a distinguished member of the

Continental Congress. Thirteen months later, he served on the committee that drafted the Declaration of

Independence. He subsequently contributed to the government in other important ways, including service as postmaster general, and took over the duties of president of the Pennsylvania constitutional convention.

But, within less than a year and a half after his return, the aged statesman set sail once again for Europe, beginning a career as diplomat that would occupy him for most of the rest of his life. In the years 1776-

79, as one of three commissioners, he directed the negotiations that led to treaties of commerce and alliance with France, where the people adulated him, but he and the other commissioners squabbled constantly. While he was sole commissioner to France (1779-85), he and John Jay and John Adams negotiated the Treaty of Paris (1783), which ended the War for Independence.

Back in the United States, in 1785 Franklin became president of the Supreme Executive Council of

Pennsylvania. At the Constitutional Convention, though he did not approve of many aspects of the finished document and was hampered by his age and ill-health, he missed few if any sessions, lent his prestige, soothed passions, and compromised disputes.

In his twilight years, working on his Autobiography, Franklin could look back on a fruitful life as the toast of two continents. Energetic nearly to the last, in 1787 he was elected as first president of the

Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery—a cause to which he had committed himself as early as the 1730s. His final public act was signing a memorial to Congress recommending dissolution of the slavery system. Shortly thereafter, in 1790 at the age of 84, Franklin passed away in Philadelphia and was laid to rest in Christ Church Burial Ground.

Samuel Adams' Childhood and Family :

Samuel Adams was born on September 27, 1722 in Boston, Massachusetts. He was one of twelve children born to Samuel and Mary Fifield Adams. However, only two of his siblings would survive beyond age three. He was a second cousin to

John Adams

, the second president of the United States. Samuel Adams' father was involved in local politics, even serving as a representative to the provincial assembly.

Education:

Adams attended Boston Latin School and then entered Harvard College at the age of 14.

He would receive his bachelor's and master's degrees from Harvard in 1740 and 1743 respectively. Adams tried numerous businesses including one he started on his own.

However, he was never successful as a commercial businessman. He took over his father's business enterprise when his father died in 1748. At the same time, he also turned to the career that he would enjoy for the rest of his life: politics.

Samuel Adams' Personal Life:

Adams married in 749 to Elizabeth Checkley. Together they had six children. However, only two of them, Samuel and Hannah, would live to adulthood. Elizabeth died in 1757 soon after giving birth to a stillborn son. Adams then married Elizabeth Wells in 1764.

Early Political Career:

In 1756, Samuel Adams became of Boston's tax collectors, a position he would keep for almost twelve years. He was not the most diligent in his career as a tax collector, however. Instead, he found that he had an aptitude for writing. Through his writing and involvement, he rose as a leader in Boston's politics. He became involved in numerous informal political organizations that had a large control over town meetings and local politics.

Beginning of Samuel Adams' Agitation Against the British:

After the French and Indian War that ended in 1763, Great Britain turned to increased taxes to pay for the costs that they had incurred for fighting in and defending the

American colonies. Three tax measures that Adams opposed were the Sugar Act of

1764, the Stamp Act of 1765, and the Townshend Duties of 1767. He believed that as the British government increased its taxes and duties, it was reducing the individual liberties of the colonists. This would lead to even greater tyranny.

Samuel Adams' Revolutionary Activity:

Adams held two key political positions that helped him in his fight against the British. He was the clerk of both the Boston town meeting and the Massachusetts House of

Representatives. Through these positions he was able to draft petitions, resolutions, and letters in protest. He argued that since the colonists were not represented in Parliament, they being taxed without their consent. Thus the rallying cry, "No taxation without representation."

Adams argued that colonists should boycott English imports and supported public demonstrations. However, he did not support the use of violence against the British as means of protest and supported the fair trial of the soldiers involved in the Boston

Massacre .

In 1772, Adams was a founder of a committee of correspondence meant to unite

Massachusetts towns against the British. He then helped expand this system to other colonies.

In 1773, Adams was influential in fighting the Tea Act. This Act was not a tax and, in fact, would have resulted in lower prices on tea. The Act was meant to aid the East India

Company by allowing it to bypass the English import tax and sell through merchants it selected. However, Adams felt that this was just a ploy to get colonists to accept the

Townshend duties that were still in place. On December 16, 1773, Adams spoke at a town meeting against the Act. That evening, dozens of men dressed as Native

Americans, boarded three tea ships that sat in Boston Harbor and threw the tea overboard.

In response to the Boston Tea Party, the British increased their restrictions on the colonists. Parliament passed the "Intolerable Acts" that not only closed the port of

Boston but also limited town meetings to one per year. Adams saw this as further evidence that the British would continue to limit the colonists' liberty.

In September, 1774, Samuel Adams became one of the delegates at the First

Continental Congress held in Philadelphia. He helped draft the Declaration of Rights. In

April, 1775, Adams, along with John Hancock, was a target of the British army advancing on Lexington. They escaped, however, when Paul Revere famously warned them.

Beginning in May, 1775, Adams was a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. He helped write the Massachusetts state constitution. He was part of the Massachusetts ratifying convention for the US Constitution.

After the Revolution, Adams served as a Massachusetts state senator, lieutenant governor, and then governor. He died on October 2, 1803 in Boston.

John Hancock Biography

Born: January 23, 1737

Braintree, Massachusetts

Died: October 8, 1793

Boston, Massachusetts

American statesman, politician, and governor

John Hancock signed the Declaration of Independence and was a leader of the movement toward revolution in the American colonies. He later served as a president of the Continental Congress, and he was elected governor of Massachusetts for nine terms.

Early life

John Hancock was born in Braintree, Massachusetts, on January 23, 1737. His parents were John Hancock, a Harvard graduate and minister, and Mary Hawke. After the death of his father when Hancock was seven, he was adopted by his uncle, a wealthy Boston merchant. Hancock graduated from Harvard in 1754, served for a time in his uncle's office as a clerk, and went to London in 1760 as the firm's representative. He spent a year there. In 1763 Hancock became a partner in his uncle's thriving business.

When his uncle died in 1764, Hancock inherited the business. He was one of many who was opposed to Great Britain's passing of the Stamp Act in 1765, since the act taxed the kinds of transactions, or business dealings, his company was involved with. As a result, to avoid having to pay these taxes, Hancock ignored the law and began smuggling

(bringing in secretly) goods into the colonies.

Hancock was elected to the Massachusetts General Court in 1766 at the suggestion of other colonists who were against British interference in the colonies. Hancock had attracted attention as something of a hero after one of his smuggling ships, the

Liberty, was seized by the British. He received more votes than Samuel Adams (1722–

1803), one of the most famous American Revolutionary leaders, in the next General

Court election. Meanwhile, Hancock was threatened with large fines by Britain for the Liberty affair. Though the fines were never collected, Hancock never got his ship back.

Growing anti-British sentiment

Every time the British made a move that affected the American colonies, especially anything involving taxes, Samuel Adams and other anti-British agitators (people who stir up public feeling on political issues) spoke out against it. The Boston Massacre of 1770

(when British soldiers fired into a crowd of people who had been throwing snowballs and sticks at them, killing five) increased colonial anger toward Britain and established a tension that continued to grow. Hancock wavered for a time, but when the strength of public opinion became clear, he made the courageous announcement that he was totally committed to making a stand against the actions of the British government—even if it cost him his life and his fortune.

During the Boston Tea Party of 1773, Boston colonists disguised as Native Americans dumped three shiploads of British tea into the harbor as a protest against the British government. After the Boston Tea Party, the British passed the Boston Port Bill of 1774.

The bill ordered the closing of the port of Boston until the cost of the tea was repaid.

Hancock's reputation grew during this time to the point where he became one of the main symbols of anti-British radicalism (extreme actions trying to force change). How much of this was planned by him, and how far he had been pushed by Samuel Adams, is uncertain. What is known is that when British General Thomas Gage finally decided to try to achieve peaceful relations with the colonies, Hancock and Adams were the only two Americans to whom he refused to even consider giving amnesty (a pardon).

Continental Congress

Hancock was elected president of the Continental Congress in May 1775 and married

Dorothy Quincy in August of the same year. He hoped to be named to command the army around Boston and was disappointed when George Washington (1732–1799) was selected instead. Hancock voted for, and was the first representative to sign, the

Declaration of Independence. Although Hancock resigned as president of the Continental

Congress in October 1777, saying that he was in poor health, he stayed on as a member.

Hancock still wanted to prove himself as a military leader. However, when given the opportunity to command an expedition into Rhode Island in 1778, he did nothing to distinguish himself. Hancock was also embarrassed in 1777 when Harvard College, which he had served as treasurer since 1773, accused him of mismanaging university funds

and demanded repayment. Hancock was forced to pay £16,000 (approximately

$22,000). In 1785 Hancock admitted that he still owed £1,054 (approximately $1,500) to Harvard. This sum was eventually paid out of his estate after his death.

Elected to office

Like most public figures, Hancock had enemies. His opponents spread the word that he was a shallow man who lacked strong beliefs and was only interested in helping himself.

Nevertheless, they could not prevent his election as the first governor of Massachusetts, in 1780. He was reelected several times until retiring in 1785 just before Massachusetts went through a financial crisis. Although he claimed that his retirement was based on illness, Hancock's enemies claimed that he had seen the coming storm, which was caused in part by mistakes he had made in handling the state's money. After Shays's

Rebellion (a 1786–87 uprising by farmers and small property owners in Massachusetts who demanded lower taxes, court reforms, and a revision of the state constitution),

Hancock was reelected governor.

In 1788, Hancock was elected president of the Massachusetts State Convention to ratify, or approve, the new Constitution. He was approached by members of the Federalist

Party (an early political group that supported a strong central government) who wanted a set of amendments added to the document. They supposedly hinted that if Hancock presented the amendments, they would help him to be named president if Washington declined the job. The truth of this story has never been confirmed. In the end, Hancock did offer the amendments, and Massachusetts ratified the Constitution. Washington accepted the presidency, and Hancock remained as Massachusetts governor, his popularity unchallenged. He died in office on October 8, 1793.

Top Ten Things to Know About George Washington

George Washington was the first President of the United States of America and a champion for the people during the

Revolutionary War against England. He was a man of principle and will always hold an important, highly regarded place in

American History.

1. People Should Be Their Own Masters

George Washington believed that people should be their own masters, that they would accomplish more and live better lives as well with liberty as opposed to doing without. As an interesting side note, Washington was the only Founding

Father who freed his slaves and favor of their freedom.

2. President Before the White House Was Built

He became president before the White House was built and was the only president who didn't live in Washington D.C.

There are many different cities, town, and streets that are named after Washington. The nation's capital, 31 counties and

17 cities are named after him.

3. Surveyor and Planter

Long before he got into politics, George Washington was a surveyor and planter. He introduced the mule, a crossbreed between a male donkey and a female horse, to American agriculture. Washington also grew marijuana on his farm to help stabilize the soil and to promote the industrial value it had as hemp.

4. Unanimous Vote in the Electoral College

The way that presidents are elected was a very important issue during the time of the 13 original colonies and the founding of the nation. The founding fathers wanted to ensure that the election processes were just and that the people were able to choose. Washington was the only president to ever be elected by a unanimous vote in the Electoral College.

It is also doubtful that this will ever happen again.

5. Shortest Inauguration Speech Ever

George Washington served two terms as president. The inauguration speech before a president takes office is very important and is viewed as a historical event. Washington's second inauguration speech was the shortest ever given at only 135 words long. He was known for being a great inspiration to many people even with his short speech.

6. General of the Armies of Congress

George Washington commanded the Continental Army and was a four-star general in his military career. After his death and on the order of Gerald Ford, Washington became the General of the Armies of Congress. Ford believed that the first president of the nation should also be the holder of the highest military position.

7. The Only Title That Has Remained The Same

Governments worldwide have changed since the election of George Washington. When he was elected, there was a king in France, an emperor in China, a shogun in Japan and a czarina in Russia. The political structures of all these nations have changed since Washington was president and the only title that still remains is that of president.

8. 1st President on a Postage Stamp

Washington was the first president to ever appear on a postage stamp. He is also printed on the one dollar bill, which is the most commonly looked at and used bill of American currency.

9. Famous Relatives

Washington was related to several other very important people in world history. He was a half first cousin to James

Madison who was also a very important American Revolution. He was also a second cousin seven times removed from

Queen Elizabeth II and an eighth cousin six times removed from Winston Churchill.

10. Dentures

Washington had very few teeth and didn't have dentures at the time of his first inauguration. At other times in his life, he wore dentures made of human teeth, ivory and even lead.