Attention grabber-Digestion-Curious case of St Alexis

advertisement

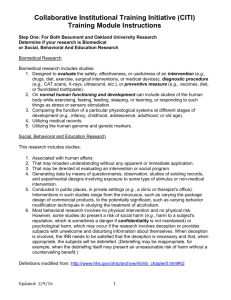

Alexis St. Martin: living science experiment Alexis St. Martin was a French-Canadian fur trader working at Fort Mackinac in the 1820s when he was shot in the stomach. A gun blast to the abdomen spelled death for almost every victim of the time, but St. Martin, for some reason, didn't die. His injury provided the fort's doctor, Dr. William Beaumont, with a rare opportunity to study the human digestion process. Through Dr. Beaumont's studies, St. Martin became a living science experiment. After Years of Failure, Finally a Break In the 1820s, there was no possible way of knowing what happened to a piece of food after someone swallowed it. Looking at a corpse would do no good because the digestion process had ceased for that person. Scientist and doctors could get a good view of the inside of the stomach, but not while it was digesting food. Questions like these were probably asked, theorized about, experimented about, hashed, and re-hashed over and over with little success or satisfaction. What happens between when food goes in and when it comes out? How does the stomach work? What role does it play in digestion? How is food digested? What gases/liquids/creatures break food down? Do different types of foods break down differently? How long does the digestion process take? How do we find out? Enter this fabulous opportunity: a young man with a gaping stomach wound who is still alive and digesting. The perfect occasion for Dr. Beaumont to conduct experiments on the stomach. Dr. Beaumont's Experiments These are just a sampling of the items Dr. Beaumont placed into or took out of Alexis St. Martin's stomach to observe the results. Placed into stomach: o Pieces of beef o Vegetables o Fish o Raw foods o Cooked foods Taken out of stomach: o Gastric juices o Pieces of stomach lining Beaumont experimented with different types of foods to answer the question "Do different types of foods digest differently?" and extracted gastric juices to research how they affect food to break it down. Beaumont and St. Martin published a book in 1833 about their work called, Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice, and the Physiology of Digestion. St. Martin is listed as a coauthor, but no one is really sure why since many historians doubt he had anything to do with the actual writing of the book. Beyond the Experiments Alexis St. Martin moved back to Canada in 1825. He and Beaumont met up once more, in Washington DC in 1832, to conduct the experiments published in the book. He lived there with his wife and children until his death in 1880. He lived his life from the age of 28 on with a hole in his side. St. Martin's family was so angered by the number of doctors, scientists, and curio hunters who showed up after his death wanting to examine his body that they allowed his body to rot before burrying it in an unmarked grave to ensure that no one could perform any further experiments on him. Dr. William Beaumont left the Army Medical Service for good in 1839 and moved to St. Louis to start a private medical practice. He lived there with his wife, Deborah, until his death in 1853. Most of the body’s serotonin, a major moodinfluencing hormone, is made not in the head but in the stomach lining. Chemistry of a cheap date: Women produce only 60 percent as much alcohol dehydrogenase, the enzyme that neutralizes booze, as men do. Achalasia, a rare condition that prevents swallowing, can be treated by a shot of Botox, which relaxes the esophageal sphincter—and undoubtedly makes it look years younger. Pica, an eating disorder in which sufferers develop an appetite for nonnutritive substances such as paint and dirt, affects up to 30 percent of young children. Its cause is unknown but possibly linked to subtle mineral deficiencies. Your stomach’s primary digestive juice, hydrochloric acid, can dissolve metal, but plastic toys that go down the hatch will come out the other end as good as new. (A choking hazard is still a choking hazard, though.) Same with crayons, hair, and chewing gum—all of which will pass through within a few days, no matter what you’ve heard. You, however, are easily digestible. The pain of pancreatitis comes from fat-digesting enzymes leaking from the pancreatic duct system into surrounding tissues, literally eating you from within. Water, enzymes, base salts, mucus, and bile create about two gallons of liquid that enters the large intestine. Only six tablespoons or so comes out. Without the colon’s marvelous ability to recover bodily fluids, animals could not survive on dry land. Brown is the new green: In 2005 the Ashden Award for Sustainable Energy was given to a Rwandan prison that used the methane from human feces to fuel cooking stoves.