File

advertisement

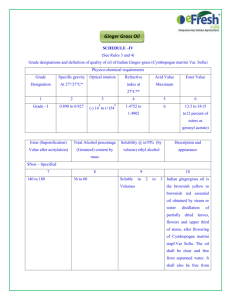

The Effects of Ginger Extract on Chemotherapy- induced Nausea and Vomiting Adam Aguilera & Joanna Bundros NFSC 345: Fall 2013 Introduction Chemotherapy patients experience many distressing side effects that decrease their quality of life, including a high prevalence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV). Besides physiological discomfort, CINV is concerning due to decreased nutrient intake, hydration status, depression, and decreased likelihood of following the therapy regimen. 1 Although general chemotherapy treatment involves use of antiemetic medications, a large majority of patients still suffer from various forms of nausea and vomiting, including acute, delayed and anticipatory.1,2 Acute nausea is nausea occurring in the first 24 hours of treatment, whereas delayed nausea occurs after 24 hours and may persist for a week. Anticipatory nausea occurs before patients receive chemotherapy, in those patients who have received previous chemotherapy treatments. 1,3 About a third of chemotherapy patients being given traditional antiemetics still experience acute nausea and vomiting, and up to 70% of patients still experience delayed and anticipatory CINV.1 The high prevalence of CINV chemotherapy patients shows that the current medication regimen is not alleviating these symptoms for the majority of patients. It is clear that additional treatments for CINV are needed, which provided motivation to research additional supplements that are being explored as possible treatments to better manage these symptoms. There have been studies conducted looking at the ability of ginger supplementation to reduce the prevalence of CINV in chemotherapy patients who are concurrently receiving the standard antiemetic medications. Ginger (zingiber officinale) has been used for thousands of years by many cultures as a treatment for digestive problems such as nausea and vomiting. Ginger can be used fresh, dried or as an extract. The active components of ginger that appear to alleviate digestive problems are gingerols found in the root and shogaols found in dried ginger .3 Ginger has been studied in relation to alleviating the frequency and severity of CINV, and has produced varying results that both support and negate the efficacy of the use of ginger for CINV management. A randomized trial done on cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy and taking a standard 5-HT3 receptor antagonist antiemetic drug, showed a significant reduction in severity of nausea symptoms with the addition of ginger extract.2 On the contrary, another randomized trial of chemotherapy patients given ginger supplementation while also taking an 5HT3 receptor antagonist and/or aprepitant drugs for CINV, showed no significant difference in occurrence of CINV or in severity of symptoms. 3 Additionally, patients receiving both the aprepitant anti-emetic drug and the highest dose of ginger supplementation had more severe nausea symptoms than those just receiving the aprepitant. While these trials show that the current research is mixed on the specific role of ginger extract in relation to CINV, the conclusion of ginger supplementation significantly reducing in the severity and prevalence of symptoms when partnered with the established protocols is best supported by the studies we examined.1, 2 Ginger appears to be a helpful anti-emetic agent for patients undergoing chemotherapy and is deserving of further investigation in additional clinical trials to better understand its efficacy in treating CINV. Discussion of Studies Study Objectives, Design, and Methods The objective of the study by Ryan et al was to determine if ginger supplementation could be an effective treatment for reducing severity of CINV in patients receiving standard antiemetics. The study design was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled dose-finding clinical trial. Patients were included if they currently had cancer, were over 18, had received at least one round of chemotherapy, and were planning to receive additional chemotherapy. They had to be receiving a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist drug and have experienced nausea during treatment. The intervention was done in 23 oncology clinics on the 744 patients meeting the inclusion criteria, and patients were randomly assigned to receive either a placebo 6 times daily (extra virgin olive oil capsules), or purified ginger capsules 6 times daily totaling 0.5 grams, 1.0 grams, or 1.5 grams of ginger. All subjects took their assigned treatment twice a day for six days, beginning three days prior to when their chemotherapy began. Patients used validated reporting questionnaires to record the prevalence and severity of any nausea experienced, as well as quality of life. Statistical analysis was done on the 576 patients who both completed baseline measures prior to the intervention, and gave needed data during the following rounds of receiving the medication. Results and Conclusions by the Researchers Patients were most commonly female, white, around 50 years of age, with breast, lung, or a form of GI cancer. Statistical results showed that all doses of ginger significantly reduced the occurrence of acute CINV compared to the placebo (p=0.013 and 0.003). The most effective doses in reducing prevalence of acute CINV were 0.5 g and 1.0 g of ginger per day. Other forms of nausea did not show a significant relationship to ginger supplementation. The authors concluded that ginger supplementation in moderate doses during chemotherapy had a beneficial effect of reducing the prevalence of acute CINV, in patients also taking a standard anti-emetic, making it a valuable additional treatment for CINV. Study Strengths and Weaknesses Strengths included the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study design, because this removes possible bias from either the patient or the administrator knowing whether the ginger or placebo has been taken. The randomization also reduces potential confounding variables associated with participants had they not been randomized. The large sample size, as well as including only subjects with complete information were also strengths. Having a large sample size better reflects the population sampled from, and decreases the chance that what was observed was due to chance. Additional strengths were the use of standardized ginger and placebo capsules all manufactured from the same company, made in ways that made them look and smell the same. This eliminated potential confounding variables and bias that would exist had there been variation in how the capsules were made, or appeared to the participant taking them. Counts of capsules were also done at the end of each round of ginger or placebo given to subjects, which is a strength because it better ensures compliance with the intervention. The use of validated questionnaires for determining nausea severity and quality of life were also study strengths, since these tools have previously been determined to accurately measure these variables in previous studies. Another study strength regarding accurately examining acute nausea was excluding nausea reported on days/times when it was not likely patients received prior chemotherapy treatment. This was a strength because it more strongly identified only acute nausea occurrence, and reduced the chance of accidentally including delayed or anticipatory nausea in the analysis. Authors also offered explanations from previous literature as to why the highest dose of ginger may not have been as effective, which confirmed the validity of their findings. One possible weakness is that the majority of subjects were white women around 50 years old, who most commonly had breast, lung, or GI cancer. This is a possible weakness because this may introduce unknown confounding variables due to the subjects being similar in these ways. Additionally, it may limit the generalizability of the study results, since these demographics are very similar. An additional weakness is the occurrence of nine reported adverse events such as rashes, flushing and heartburn from patients taking the ginger. Although this number is not very high, we felt it was a weakness because it was discussed very little in the paper. Another weakness was that they did not control for how strong of a chemotherapy treatment was received, or how severe nausea was before the intervention began. This is a weakness because perhaps patients receiving different chemotherapy doses would show a significant difference in relation to ginger effectiveness, and this was not explored. There was also a small effect size for severity of nausea between treatment and control (even though the pvalue was significant), which is a weakness because it questions the power of the findings. However, the authors point out that this would probably had changed had they limited enrollment just to patients with moderate or severe nausea. After analysis of the study conclusions, strengths and weaknesses we support the researcher’s conclusions of ginger supplementation having a significant role in treating acute CINV. We support this conclusion because there were extremely significant p-values for all analyses relating to acute CINV (p=0.013 and 0.003) from a large sample size, and findings were in line with previous studies which adds validity to findings. Additionally, researchers were very careful in their identification of acute nausea episodes in their analysis, and we feel the small effect size was probably due to how the data was organized for analysis, and not due to the findings not being significant. Study Objectives, Design, and Methods The second study, written by Suzanna M. Zick and colleagues, was designed to research the effect of multiple doses of powdered ginger extract versus a placebo for reducing the occurrence and severity of delayed and acute CINV. The main objective focused on delayed CINV since previous studies had only shown significance with acute stages. The study also wanted to assess the safety of varying ginger doses. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was initiated to study the use of ginger on patients recruited from oncology clinics and other sites affiliated with the National Cancer Institute’s oncology center. 162 participants were recruited, who were 18 or older, diagnosed with cancer, receiving chemotherapy, and had experienced CINV during one or more prior rounds of treatment. Patients were excluded if they were receiving more than one dose of chemotherapy daily, also receiving radiation that may cause nausea or vomiting, using medications like Coumadin or aspirin, or if they were pregnant or nursing. All patients were randomized to receive 1.0g ginger (4 capsules ginger, 4 capsules placebo), 2.0g ginger (8 capsules ginger) or a placebo (8 capsules placebo) daily for 3 days. Each capsule contained a standardized 250 mg of dry ginger extract. Subjects were also randomized to concurrently receive either a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and/or aprepitant to help manage CINV. Validated questionnaires and Likert scales were used to separately determine occurrence and severity of both acute and delayed CINV experienced by patients. Safety was determined by both talking with subjects, and looking through hospital records or documented adverse events relating to the ginger supplementation. Results and Conclusions by the Researchers Researchers saw no significant difference between any of the ginger doses in severity or prevalence of either acute or delayed CINV, compared to the placebo. This lack of significance remained, even when data was analyzed by whether or not the participant had received the aprepitant drug. However, researchers did observe that for patients receiving the aprepitant drug, the highest dose treatment group (2 g ginger/day) showed a trend of higher severity of delayed nausea compared to the low dose and placebo group, although not statistically significant (p=0.07). Authors concluded that ginger extract has no benefit on either the occurrence or severity of acute and delayed CINV for patients receiving chemotherapy, when taken concurrently with standard antiemetic drugs. They also concluded that high doses of ginger extract may exacerbate delayed CINV when taken with an aprepitant medication. Study Strengths and Weaknesses Study strength included the use of standardized ginger capsules from the same manufacturer, as well as using dosages based on previous clinical trials. These are strengths because using capsules from the same manufacturer eliminates possible confounding variables had they been made differently, and using dosages based on previous clinical trials increases validity and generalizability of findings. Additional strengths included use of validated questionnaires to determine occurrence and severity of CINV, because these tools have been previously shown to accurately measure these variables. The extensive assessment of safety of ginger supplementation was also a strength, and was done by use of talking to participants, and checking hospital adverse event documentation. This is a strength because they took safety of participants very seriously, and also were able to statistically show there was not a difference in occurrence of adverse events between placebo and ginger groups. An additional strength was the equal distribution of the aprepitant drug between all treatment groups. This is a strength because it increases the significance of any findings involving this drug and ginger. Many covariates were also controlled for in statistical analysis, including presence of baseline CINV, how strong of a chemotherapy treatment was being received, and whether an aprepitant was being taken. Controlling for these covariates is a strength because it increases the likelihood that any observed outcomes are due to ginger, and not to these factors. There was also a high retention rate, and strong adherence to following the medication dosages, which increases validity of the results. Weaknesses included that the intervention only lasted for 3 days. This is a weakness because perhaps a longer time is needed to examine CINV, and especially delayed CINV. A major weakness was also that participants were significantly able to guess which treatment group they were in, based in part on the flavor. This is a weakness because it introduces bias from the patient knowing they are getting either the placebo or the treatment. When patients can correctly identify their treatment, the study is no longer really a “double-blind” trial. An additional weakness is the researchers asking participants to return all capsules not taken to them at their third day visit. This is a weakness because perhaps participants would not actually return all capsules they had not taken, if they were concerned administrators would be upset that they had not taken them all. This could skew results, if patients were believed to have consumed all their dosages. A more accurate method would have been to observe the capsules being taken by each patient. Lastly, a weakness was that they point out several published studies with results in contrast to theirs, which may call into question the validity of their findings. After analysis of the study conclusions, strengths and weaknesses we do not support the researcher’s conclusions of ginger supplementation having no effect on severity or occurrence of acute or delayed CINV. We do not support this conclusion because this was a very short trial, and we don’t feel it was long enough to significantly analyze both acute and delayed CINV occurrence. We also decided this due to participants being mostly aware of which treatment group they were in, as well as multiple studies reporting the opposite of the results of this study. Conclusion and Recommendations Based on our analysis of this literature relating to ginger supplementation for treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, we conclude that ginger is an effective treatment for reducing occurrence and severity of acute CINV. Due to the significant p-values associated with ginger as a treatment, the large sample size, as well as the careful process of identifying acute nausea episodes for analysis, we feel these strongly support this conclusion. Additionally, although the second study did not show an association between ginger supplementation and CINV, due to the short study duration and the issues with the double-blind portion of the study sample, we feel it is more likely that in fact ginger does have an association with CINV. Our recommendations for further research include randomized double-blind clinical trials of longer duration, to better examine an association between ginger and delayed CINV. We also recommend additional in-vitro and in-vivo studies examining the safety of taking ginger supplements in high doses concurrently with aprepitant medications. Lastly, we recommend further trials regarding anticipatory nausea, as it appears to be the least understood form, although it is highly prevalent among chemotherapy patients. References: 1. Panahi Y, Saadat A, Sahebkar A, et al. Effect of ginger on acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a pilot, randomized, open-label clinical trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012; 11: 204-211. 2. Ryan JL, Heckler CE, Roscoe JA, et al. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) reduces acute chemotherapy-induced nausea: A URCC CCOP study of 576 patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012; 20: 1479-1489. 3. Zick SM, Ruffin MT, Lee J, et al. Phase II trial of encapsulated ginger as a treatment for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Support Care Cancer. 2009; 17: 563-572.

![[Physician Letterhead] [Select Today`s Date] . [Name of Health](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006995683_1-fc7d457c4956a00b3a5595efa89b67b0-300x300.png)