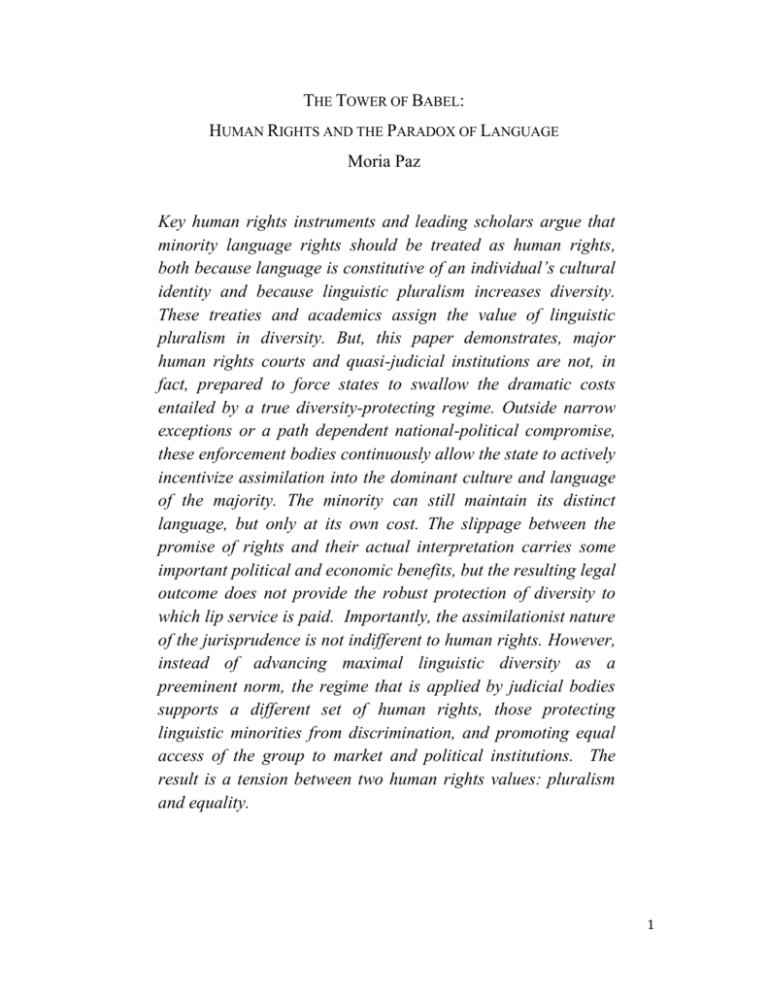

The Tower of Babel - Columbia Law School

advertisement