Cultural Proficiency - University of Idaho

advertisement

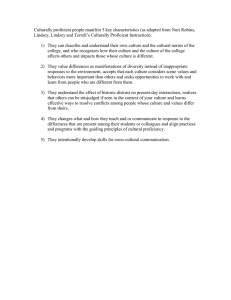

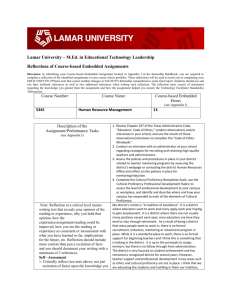

Cultural Proficiency Philosophy: We believe that diversity enriches the learning environment and that all individuals have worth and should be treated with dignity and respect. We welcome a variety of cultural, economic, and experiential backgrounds including, but not limited to, variation with respect to language, race, culture, religious belief, gender, sexual orientation, age, ability, veteran status, and geographical location. Therefore, we believe that the Cultural Proficiency Model best informs our preparation of educators in the area of diversity as this approach does not simply prize the individual, but focuses on the culture of an organization. The Cultural Proficiency Model uses an inside-out approach and considers those who are insiders in the organization, encouraging reflection on self understandings and values. It relieves those identified as outsiders, members of excluded or marginalized groups, from the responsibility of doing all the adapting. This approach acknowledges and respects the current values and feelings of people, encouraging change without threatening feelings of worth. Cultural proficiency is reflected in the way an organization treats its employees, its constituents, and its community. Administrators, teachers, staff, parents, students, and the community welcome and create opportunities to better understand whom they are as individuals, while learning how to interact positively with people who differ from themselves. In summary, cultural proficiency is the policies and practices of the organization, or the values and behaviors of an individual, which enable that agency or person to interact effectively in a culturally diverse environment. Professional Commitments and Dispositions We endeavor to promote the development of educators who can be secure in their identities, acknowledge their predispositions, biases, and limitations, and actively and critically engage in culturally proficient leadership and teaching. Culturally proficient leaders and teachers begin with accepting and valuing each student and acknowledging what each student brings to the community. They nurture development, individual ability, and talent while creating an equitable classroom environment. Culturally proficient leaders confidently deliver programs and services, knowing that their community of learners genuinely value diversity. Teachers, administrators, school counselors, support staff, and related professionals show respect to one another and to collective efforts to educate every student. When all of the participants are deeply involved in the developmental process, there is broader based ownership, making commitment to change more likely. As a result, in a culturally proficient organization, the culture of the organization promotes inclusiveness and institutionalizes processes for learning about differences and for responding appropriately to those differences. In an organization it is the organizational policies and practices that reflect a positive diverse environment. In an individual, it is one’s values and behaviors that enable effective interaction in a diverse environment. References Cross, T. L.; Bazron, B. J.; Dennis, K. W.; Isaacs, M. R. (1989). Towards A Culturally Competent System Of Care: Volume 1 - A Monograph on Effective Services for Minority Children Who Are Severely Emotionally Disturbed. Washington: CASSP Technical Assistance Center Georgetown University Child Development Center Dover, W. (1999). Inclusion: The Next Step Managing Diversity of Needs in the Classroom. Manhattan, Kansas: The Master Teacher, Inc. Gartner, A.; Kerzner Lipsky, D. (1998). Inclusive Education – Mainstreaming all of America’s children. Social Policy, 28, (No. 3), 73-76 Disabilities Education Act. NCERI Bulletin, Spring 1998. National Center of Education: Restructuring and Inclusion, 2, (No. 2) 2-5 Individual's With Disabilities Education Act amendments 1997, 2002. In. Retrieved April 17, 2005, from http://www.ed.gov/about/offices/list/osers/policy.html): President's Commissions in Special Education. 2002. Lindsey, R. B.; Roberts, L. M.; CambellJones, F. (2005). The Culturally Proficient School: An Implementation Guide for School Leaders. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press Lindsey, R. B.; Roberts, L. M.; Terrell, R. D. (2003). Cultural Proficiency: A Manual for School Leaders. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press Patterson, J. P. a. J. (April 2004).Sharing The Lead. Educational Leadership, 61(No. 7), 74-78. Portin, B. (2004). The Roles That Principals Play. Educational Leadership, 61 (No. 7), 14-18. Roach, V. (1995). Supporting Inclusion; Beyond the Rhetoric. Phi Delta Kappan, 77 (No. 4), 295-299 Robins, K. N.; Lindsey, R. B.; Lindsey, D. B.; Terrell, R. D. (2002). Culturally Proficient Instruction: A Guide for People Who Teach. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press Sapon-Shevin, M. (2003). Inclusion: A Matter of Social Justice. Educational Leadership, 61(No.2), 25-28 Sergiovanni, T. (2004). Building a Community of Hope – At the heart of each school, a realistic optimism must prevail. Educational Leadership: journal of the Department of Supervision and Curriculum Development, N.E.A., 61 (No. 8), 33-39 Sergiovanni, T. (2005). Strengthening The Heartbeat: Leading and Learning Together in Schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Tomlinson, C. A. (2003). Deciding to Teach Them All. Educational Leadership, 61 (No. 2), 6-11 Villa, R.; Thousand, J. (2003). Making Inclusive education Work. Educational Leadership, 61 (No.2), 19-23 Villa, R.; Thousand, J. (2005). Creating an Inclusive School. (2nd Ed.). Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Supervision. Zaretsky, L. (2004). Advocacy and administration: From conflict to collaboration. Journal of Educational Administration, 42(2), 270.