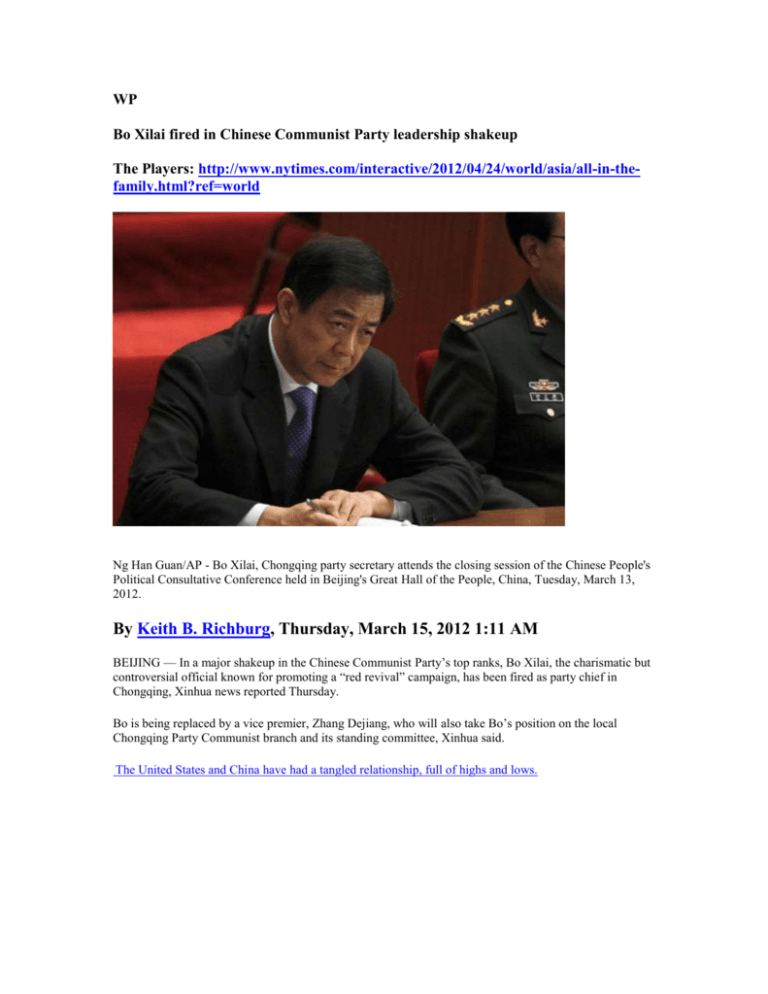

Bo Xilai Fired: Chinese Communist Party Shakeup

advertisement