THE PHILLIPS CURVE 2011

advertisement

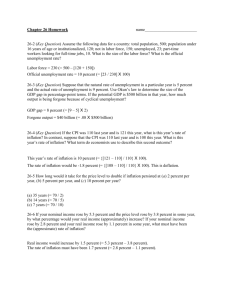

THE PHILLIPS CURVE The origins of the Phillips curve In 1958, an economist called Phillips published a paper stating that there was a trade off between the rate of change of money wages and unemployment rate. But it was not some brilliant theory that he had invented, he had simply collected data on wage inflation and unemployment for every year between 1861 and 1957, plotted a scatter diagram and drawn a line of best fit. This might sound a bit useless, but when you think of how closely related the rate of change of money wages is to the rate of inflation, this relationship became very significant. If in the diagram below,the Government wanted to reduce unemployment below 5% they would have to accept that this would cause inflation. But Governments could by manipulating AD choose the combination of inflation and unemployment in the economy. This was great for the government. Although they could not control unemployment and inflation at the same time, they now had a ‘guide’ that told them exactly how much inflation to expect for a given reduction in unemployment. Equally, if inflation was high, they could see how much unemployment to expect for a given cut in the rate of inflation. Keynesian economists used the Phillips curve as a proof that their interpretation of AS/AD analysis existed, namely that AD policies could reduce unemployment, but if the economy was operating close to full employment this could only be achieved by increasing inflation. This is shown in the diagram below. LRAS and the Phillips Curve Price Level LRAS P2 P1 AD2 AD1 Ye Y1 Real National Output (Y) Why did the relationship hold? If the government decided to cut unemployment through an expansionary fiscal or monetary policy Why would a reduction in unemployment cause the inflation rate to rise? If the government decided to cut unemployment through an expansionary fiscal or monetary policy the resulting shift in the aggregate demand curve would increase output, which could only be accommodated by employing more labour.Diminishing The upwards pressure on wages from labour shortages causes wage increases. This, in turn would cause an inflationary rise in the price level. So unemployment fell, but inflation rose. It was also a powerful argument for the use of active fiscal policy, in that the Government could use fiscal policy to get the correct balance of both unemployment and inflation. However the Phillips curve has not been without controversy. Soon after Phillips suggested this, the data seemed to prove him wrong, as this chart shows: There seems to have been no fixed relationship between inflation and unemployment as Phillips had argued The breakdown of the original Phillips curve Most of the politicians, who took this relationship as gospel, did not appreciate fully one simple point. This ‘Phillips curve’ was not some theory that was cast in stone, but merely empirical data that showed a historical correlation between 2 variables. The relationship started to break down as early as the late 60s. Inflation and unemployment started rising together. An economist called Friedman tried to explain what was going on and why stagflation had occurred. This is summarized below: In the diagram on the next page, you can see two short run ‘normal’ looking Phillips curves and a vertical long run Phillips curve. Let us assume that the economy begins at point A, with 0% inflation and a rate of unemployment of Un. The government decides that it wants unemployment to be lower. It increases aggregate demand by, say, building some new roads. In order to attract the required workers, the money wage is increased. Previously unemployed workers take the bait (frictionally, or structurally unemployed), unemployment falls to U1 at a cost of increasing inflation P1. The economy moves from point A to point B along the short run Phillips curve SRPC1. Note that inflation has been 0% and this means that workers expect future inflation to be 0%. They took the job with increased money wages expecting inflation to stay at 0% so that the real wage is higher. Workers only increase their supply of labour in response to an increase in wages. But, the increase in money wages forced the inflation rate up to P1 say this is 3%. The new workers did not realise this straight away. They initially suffer from money illusion. Before long the workers realise that they have, in a sense, been duped. Real wages have not increased at all. The new workers were not prepared to work at this lower real wage rate, so they withdraw their labour services and become unemployed again. The economy moves from point B to point C. Unemployment is back up to Un, but inflation stays where it is because money wages have not fallen back to their original level (workers now assume inflation is 3% and therefore work this into their pay bargaining). The economy is now on a different short run Phillips curve (SRPC2) with expected inflation equal to 3%. If the government tries to reduce unemployment again, the same thing will happen. The economy will move from point C to D and then to E. In other words, every time the government tries to reduce unemployment below Un, it manages to do it in the short run, but as the workers realise the money illusion unemployment returns to its’ natural rate in the long run., but at a higher, and permanent, level of inflation. Hence, the long run Phillips curve is the vertical line LRPC. Unemployment can be higher than Un in the long run, but not below Un. The level of unemployment Un is often called the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) or the Natural rate of unemployment. Quite simply, at Un, inflation is non-accelerating. If unemployment is below Un, then inflation accelerates. Once the government works out that reducing unemployment below Un in the long run is not possible, it has to get inflation down to where it was before. It can do this, but only by getting workers’ expectations of future inflation down to where they were before. The Expectations-Augmented Phillips Curve Long Run Phillips Curve (LRPC) Wage Inflation (%) D P2 E P1 C B SRPC 2 F SRPC1 U1 A Un Unemployment Rate (%) Given that there will always be some voluntary unemployment in an economy, this level of unemployment is often referred to as the natural rate of unemployment, because it occurs, in a sense, naturally. It occurs ‘naturally’ even when the economy is at its long run equilibrium. The natural rate of unemployment The implication of the above analysis is that there will always be some unemployment in an economy. This seems to be true looking back at past data. The factors that could affect or change the natural rate of unemployment/NAIRU are numerous and include: An increase in trade union power, which would reduce the fear of unemployment and therefore cause an upward shift in real wages and reduce flexibility in the labour market An increase in the level of skills mismatch in the labour market which would increase structural unemployment and thus the natural rate would also increase Increased provision of child care has helped to reduce the NAIRU by allowing greater participation of women in the labour market Greater flexibility in the labour market (I.e. the success of policies to improve the occupational mobility of labour) would reduce skills mismatch and reduce the target real wage The factors that might unfavourably affect the level of sustainable unemployment include the following: High levels of benefits relative to wages, long duration of benefits and weak tests of job-seeking; High levels of taxation, which drive a wedge between take home pay and the cost of labour to the employer; A high degree of unionisation and union power; A low-skilled labour force; Inadequate capital stock A highly regulated labour market which may discourage recruitment (I.e.new job creation) The NAIRU/Natural rate may exist in theory – but it is difficult to identify its value in practice – and its value may change over time.