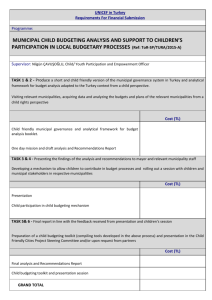

MUNICIPAL FINANCIAL SUSTAINABILITY OF CURRENT SPATIAL

advertisement