Why use peer research? - New Economics Foundation

advertisement

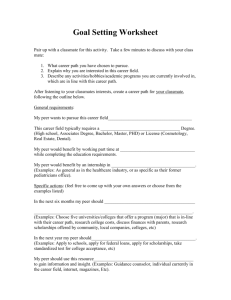

Peer Research This resource introduces an approach to peer research. It is one part of a wider set of resources that NEF has developed through the ‘Transforming Young People’s Services’ project with the intention of supporting commissioners and providers to embed coproduction and an outcomes-based approach into the design and delivery of public services. The resources in this series were concieved of and tested with commissioners and providers in Cornwall, Lambeth and Islington. They are intended to provide inspiration for methods you might use to begin coproducing an outcomes focused approach to commissioning. They do not need to be followed to the letter. In fact, they will benefit from being adapted to speicifc contexts and cicumstances. For more information about the resource or the ‘Transforming Young People’s Services project, please get in touch with Julia.slay@neweconomics.org What is peer research? Peer research is a way of designing and delivering a research project with the people who would usually be the subjects of research. It is an approach that has emerged from participatory and grass-roots research, and privileges the role of the traditionally researched as active researchers. By training peer researchers in social science methods and then working with them to set research themes, identify research questions, undertake interviews and analyse the findings, you start to break down hierarchies between researchers and the researched. This provides rich access into people’s lives and experiences. Their ways of understanding and knowing challenge professional researchers and help to ground all-too-often abstract expertise. Through peer research, you can open commissioning up to different ways of understanding people’s experience, aspirations and challenges. Why use peer research? Peer research can be a challenging but awarding approach to research. It can be particularly helpful during the insight phase of commissioning. Through peer research you will be able to: Shift the power in the research process away from professional researchers to young people. 2 Peer Research Blur distinctions between researchers and researched – or professionals and young people in research – so that they can share roles and power more equally. Help embed principles of co-production into the commissioning process. Improve research findings by tapping into the ‘lived experience’ of young people: young people are likely to frame issues differently to adults and in our experience ask unexpected questions. Gain access to a greater number of young people than through conventional research methods, especially young people you may have not had contact with before. Develop the capabilities and skills of young people through research: young people will learn technical research skills (including how to develop and undertake a research project, how to conduct semi-structured interviews etc.) and soft skills (such as leadership and team working skills). Challenges in peer research While peer research can be insightful and rewarding, there are a number of challenges that are worth keeping in mind, both before embarking on a peer research approach, and during the process itself: Peer research can be time consuming; it takes time to develop young people’s skills and ensure that they can get involved in a meaningful way. You may encounter tensions between what professionals see as important and what young people are interested in – although this can be a creative tension if well managed. It can be difficult to maintain people’s interest in research projects over a protracted period of time. Working with peer researchers can heighten ethical issues in research. It is important to remember that peer researchers are not professionally trained researchers, while the research they conduct will be insightful in ways that professional research can’t be, it may also have shortcomings in terms of research rigour. Peer research in practice Much in the same way as conventional research, there is no one way of doing peer research. Peer research, like all qualitative research, requires methodological creativity to ensure that it meets the specific needs of the project. The sessions and resources we outline below are not meant to be prescriptive. They are intended to provide some inspiration from which you might be able to design your own approach 3 Peer Research to peer research. We used these sessions and resources when working with peer researchers on a project exploring the impact of austerity measures in Birmingham and Haringey. Semi-structured interviews The main method we have used with peer-researchers is semi-structured interviews. There are two good reasons for this. Semi-structured interviews enable peer researchers to engage with their peers in conversations, enabling them to engage with the person they are speaking with in a naturalistic way. However, because the interviews are also, to some extent, structured – by a set of mutually agreed upon questions to be asked – they also provide a degree of consistency across interviews. The following session was developed as an introduction to semi-structured interviews for peer researchers we worked with in Birmingham. In this instance, we were working with peer researchers to explore the impact of austerity measures on their families and communities. We worked with a group of 15 peer researchers from a diverse range of backgrounds. Very few had any prior experience of interviewing people in a research context and some were apprehensive to begin with. However, after four sessions explaining and trialling the approach, the peer researchers gained confidence and successfully completed over forty interviews. These made an invaluable contribution to our research on Surviving Austerity. Semi-structured interviews for peer research.pptx Photo-journalism When working with young people on a peer research project in Haringey, we found that semi-structured interviews were not always the best means of engaging young people. As an alternative we developed a short photo-journalism course with a professional photo-journalist. This helped the young people to explore issues that mattered to them through photography. The piece of photojournalism below was produced by Imad, a young man from Wood Green in Haringey. Imad's Blog.docx Peer research resources 4 Peer Research We found the following resources very helpful when training peer researchers. They were developed by the Research Consortium on Educational Outcomes and Poverty (RECOUP) and can be viewed here: http://manual.recoup.educ.cam.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Main_Page Good and bad listening hand-out Question prompts, probes and encouragement Questions to avoid Activity: the experience of ‘doing’ and ‘being’ interviewed Peer research in Cornwall Cornwall’s youth services team wanted to work with young people in the county to explore their priority outcomes. Peer Research was one of the methods used to develop insight, and inform the county’s young people’s outcomes framework. The council wanted to explore four main areas. Communication: how can young people feed back to the Council and how can the Council better promote its services to young people? Outcomes: how do young people see their future in Cornwall and what are their priorities for themselves and others? Assets: what assets do young people see that they bring to their communities and each other and what assets do they identify in their communities? Rewards and incentives: what would young people need to get involved locally and volunteer? The team began by recruiting young people to take part in a residential training weekend to begin the process. Twenty five young people participated, and a core group of peer researchers was established. They then expanded this group to include a number of local schools, training a further 80 young people in peer research methods. ‘ I now have better social skills, met loads of new people and am more confident and able to talk to different people. It has changed me as I am more confident to talk about who I am’. Young Peer Researcher The peer research was carried out in schools, youth and specialist groups. The data was gathered and analysed, and a set of key themes and recommendations emerged. The research highlighted a number of things young people valued, including: Involvement in positive activities, especially sports and music; Personal qualities, rights and skills for life; Supportive family relationships and being safe at home; 5 Peer Research Jobs, careers and employment; The importance of friends and peers. From the research a number of recommendations were made. For example, the team proposed working with young people in planning a ‘curriculum for life’ to develop the skills, knowledge and values young people considered important, and to encourage Cornwall’s clubs and organisations which provide sport opportunities to prioritise the participation of young people and offer provision for those under 18 where possible. Cornwall’s peer research project illustrates an important point about how ‘services’ interact with local assets that are found beyond the council. The list of things that young people valued, discovered during Cornwall’s peer research process, showed how important support and activities outside of ‘services’ formally procured by the council are in achieving outcomes. This doesn’t mean that the role of the local authority is unimportant. Rather, it suggests that a council might need to use its networks, influence and own resources to look beyond services and dedicate resources to nurturing and supporting these aspects of people’s lives. For example, this might be through providing access to spaces where people can pursue their own projects or hold peer support groups, or by partnering with local businesses or leisure centres to apply the insight in practice. Using these methods, and others, it is possible to build up a picture of what outcomes are important to the people who will be using the service. Some of these are likely to be the same, or similar, to the outcomes which have been identified through the review process, but they may add to the existing descriptions. As far as possible, the description of these outcomes should reflect the way they are experienced and expressed by those who will use the service, or receive support. Foundations for good practice A clear process. As with any form of engagement or participation a clear process, laid out at the beginning is essential. This makes the difference between people turning up the next week or not. Peer researchers want to know what is expected of them, what they will get out of the process and when they will be finished. It is only by providing this upfront that people can make informed decisions about their participation. Involve peer researchers as early and as often as possible in the design of the research. Local ownership is absolutely central to the success or failure of a 6 Peer Research peer research project. People will go much further if they feel that they are steering the boat. If they sense that they are being co-opted into someone else’s project they will quickly lose interest and leave. Be realistic about time frames. There is a balance to be struck between having too little time and rushing the process and taking too long and it feeling too open ended with no finish line in sight. We found that people enjoyed the training sessions because they felt they were learning new things. It is worth taking some time to get the training right. Some people may get it quite quickly and in these instances it may be best to let them get on with things. Once the research has begun, set quite short deadlines. People want to have an end in sight that they can work towards. They want to know that things will be wrapped up relatively quickly and that they will be able to see the end product Make sure that support is on-going. This can take the form of periodic meetings with the peer researchers to discuss how things are going. It could also be in the form of e-mails, telephone calls or using a private facebook page. Letting go of power. To be a researcher is to be in a position of power. When we research a subject we decide how to approach the research, what questions to ask and ultimately how to represent what we are researching. Peer research demands that the lead researcher give up their power to a great extent. This can be hard. For example, when drafting interview schedules it can be very difficult not to lead the group. This doesn’t mean that you can’t have your say. It is just that you need to position your opinions as those of a member of the group and not as those of its leader. Learn to be facilitative. When leading peer research projects you should see your role as facilitative, rather than instructional. There will be times when you are teaching peer researchers, but once they have begun you should be helping them to discover their own unique style as researchers rather than imposing your own. Further Resources This short video explains how Turning Point has worked with community researchers https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1CMwUo1S2tY This short summary from Sheffield University captures some of the main considerations of the peer research methodology http://www.shu.ac.uk/_assets/pdf/hccj-ResearchMethodology.pdf 7 Peer Research When designing our peer research process we borrowed a lot of ideas and resources that were developed by the Research Consortium on Educational Outcomes and Poverty (RECOUP) and can be viewed here: http://manual.recoup.educ.cam.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Main_Page For a detailed reflection of the ethical and practical considerations look at Ros Edward’s and Claire Alexander’s chapter “Researching with Peer/Community researchers – ambivalences and tensions”, in the SAGE handbook of innovation in social research methods: http://www.uk.sagepub.com/books/Book231759