US-SYSA Coach Guide - Swampscott Youth Soccer Association

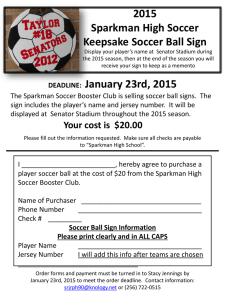

advertisement

Swampscott Youth Soccer Association- a brief compilation of guidance on coaching youth soccer US Soccer and US Youth Soccer have published a series of materials in recent years providing detailed guidance on coaching youth soccer. This will provide a brief compilation and distillation of some of that guidance, with much being direct quotes or paraphrases of the US Soccer and US Youth Soccer source materials. General: In general, young soccer players require a certain amount of uninterrupted play. This allows them to experience soccer first hand. They should be allowed the opportunity to experiment, and with that, to succeed and fail. The coach’s long-term goal is to prepare the player to successfully recognize and solve the challenges of the game on his or her own. From a developmental standpoint, the young ages are the best ones for learning soccer skills. Spend the time now encouraging this growth. By the age of 17, the capacity to pick up new motor skills begins to wane, while the ability to conceptualize team organization, tactics and strategy increases. As a coach, work with these strengths, not against them. Allow your players to develop the requisite skills in an environment where the main goal is to have fun with the ball. Have a clear idea of what you want to accomplish at practice. Create exercises/games that replicate and repeat the movements and situations that are found in soccer and that allow the player to grow comfortable and confident with the ball at his or her feet and deal with boundaries, opponents, teammates and goals. Keep in mind that soccer is a pretty simple game. If you are involved long enough, you realize that all the many little games that work are really just variations on the same basic concepts. As long as the parameters that you have established in your exercises/small-sided games are true to soccer (goals for scoring and defending), create the problem you want the kids to solve (protecting the ball while dribbling, etc.) and allow your players to be challenged and find some success, you’re on the right track. Controlling the ball is the primary skill that every other skill in soccer depends upon. With this in mind, try to encourage comfort with the ball and the confidence to use this skill creatively. Dribbling is an attempt to gain control over the ball, and so encourage the dribbler at the younger ages- don’t expect (or even ask) the players to pass until they have first mastered dribbling. Children from age 6 to 12 have an almost limitless capacity to learn body movement and coordination (motor skills). At the same time, their intellectual capacity to understand spatial concepts like positions and group play is limited. Work to their strengths. Many kids who have been involved in organized soccer will often look to pass the ball or kick it down the field as their first option. They have been taught to “share” the ball or they have learned that the best way to keep from making a “mistake” with the ball at their feet is to kick it away as fast as possible. Instead, we should encourage risk-taking and applaud effort. A major theme of the source materials is a warning against over-coaching. Unlike most team sports, soccer is a player’s game, not a coach’s game. For players to become self-reliant, the coach must not micromanage the game for them. As a player-centered sport, some coaches become disillusioned as they learn that they are the guide on the side and not the sage on the stage. In many other sports, the coach makes crucial decisions during the competition. This coach-centered perspective has been handed down to us from other sports and coaching styles of past generations. In soccer, players make tactical decisions during the match; the coach’s decisions are strategic. The ego-centric personality will find coaching soccer properly troublesome. From a training perspective, too much emphasis has been placed on a robotic drill routine that has the coach at the center of training, whereas the game itself should be the centerpiece with players at the forefront of the action. From a game perspective, players who are over-coached in matches become robotic in their performance and cannot make tactical decisions fast enough. The over-coaching comes not only from coaches, but also from spectators who constantly yell out to the players what to do and when to do it. This environment has led particularly to a weakness in transition play (from attacking to defending, and vice versa) Over-coaching in games may help to win the battle (the game) but will lose the war (the long-term development of the players). Age appropriate: It is imperative for children at the younger ages to acquire a base of general balance, coordination and agility before soccer skills. The children should be engaged in fun games with a ball at their feet, keeping it fun and enjoyable to foster a desire to play. Players is this age group are egocentric- a me, my, mine mentality. Young children do not play together; they play next to one another, meaning they do not necessarily interact as they play. This psychosocial reality is called parallel play. Each child is engaged in his or her own game and is not sharing or cooperating in a game. In soccer, this is most evident in the U6 age group and still occurs to a lesser degree through U8. Recognizing that the players will need a number of breaks for rest and water, coaches should look to get the ball quickly back into play (or just act as a rebound on the sideline) to let the kids get more of what they enjoy- playing. At U8, many activities can now be done in pairs to promote communication, cooperation and the conceptualization of soccer principles. At U10, an emphasis needs to be placed on skill development using a games-based approach. The coach is the facilitator and creator of soccer problem situations posing questions on time, space and tactical risk/safety. The repetition of technique is undertaken through fun games and dynamic activities. Training sessions should still focus on small-sided games so players have the opportunity to recognize pictures presented by the game. The golden age of learning begins with U10s and continuing with U12s is the most important for skill development. Continue establishing a solid base of technique. Develop individual skills under pressure of time, space and opponent(s) and increase technical speed. Place an emphasis on individual possession and defending, and work on combining players in pairs and small group to defend and attack. At U14, because of growth spurts typically occurring at this time in their biological growth, emphasis on agility training and core body balance training would be appropriate. Regular use of the “11+” routine (available on FIFA’s website) provides a proven standard that will prepare players for the demands of the game and assist in preventing injuries. For skills, the importance of a good first touch in receiving, passing, heading and shooting cannot be over-emphasized. An increase in technical speed is affected by using small-sided games in training sessions. Train the players to highly value maintaining possession of the ball. Possession of the ball is important both individually and as a team. The most important factors are the quality of the first touch and early movement of the 2nd attacker. If the players learn to keep the ball using team shape and movement to do so, it will help them understand defending issues better too. In the attacking third, encourage risk taking to persuade players to take on an opponent, especially in a 1 v. 1 situation and when in the opponent’s penalty area. Organizationally, the team moves together both horizontally and vertically to support each other on the attack and when defending. Singularly important in the game is mobility. More Advanced Considerations: Advance planning is a crucial component of designing effective training sessions. Training should ideally be theme-based, with a progression of activities moving from simple to complex. Various elements within an activity can also be adjusted- the amount of space, the number of players and/or balls, even strength numbers or player advantage- to optimize the effectiveness of an activity. With advance planning, economical training sessions can be devised. At its most basic level, training should not be just fitness; instead, fitness should be accomplished in an activity using a ball. The start of practice is an important time to employ economical training techniques- getting the players simultaneously moving, touching the ball and interacting with teammates might be objectives for the start of every training session in preparation for dynamic stretching. Increasing speed of play is understood to be a crucial area of development, with first touch and other technical elements important to such improvement. But “coach-directed” activities do not develop problem solving, anticipation, “reading the game” and other attributes which are critical to speed of play. As an example, consider an exercise involving dribbling where the coach calls out ”change direction.” Such an exercise might develop technical speed, but is divorced from other important components of speed , such as visual speed (what the player sees and when), anticipatory speed (anticipating where, when and how fast to move), and reactive speed (movements of others creating new openings and blocking others). Only game-like environments nurture these types of speed. Coaches would do better if they provided problems for the players to solve and aims for them to reach, rather than directing how players should react to each situation. Source Materials (available at the US Soccer website): Best Practices for Coaching Soccer in the United States U.S. Soccer Curriculum US Youth Soccer Player Development Model