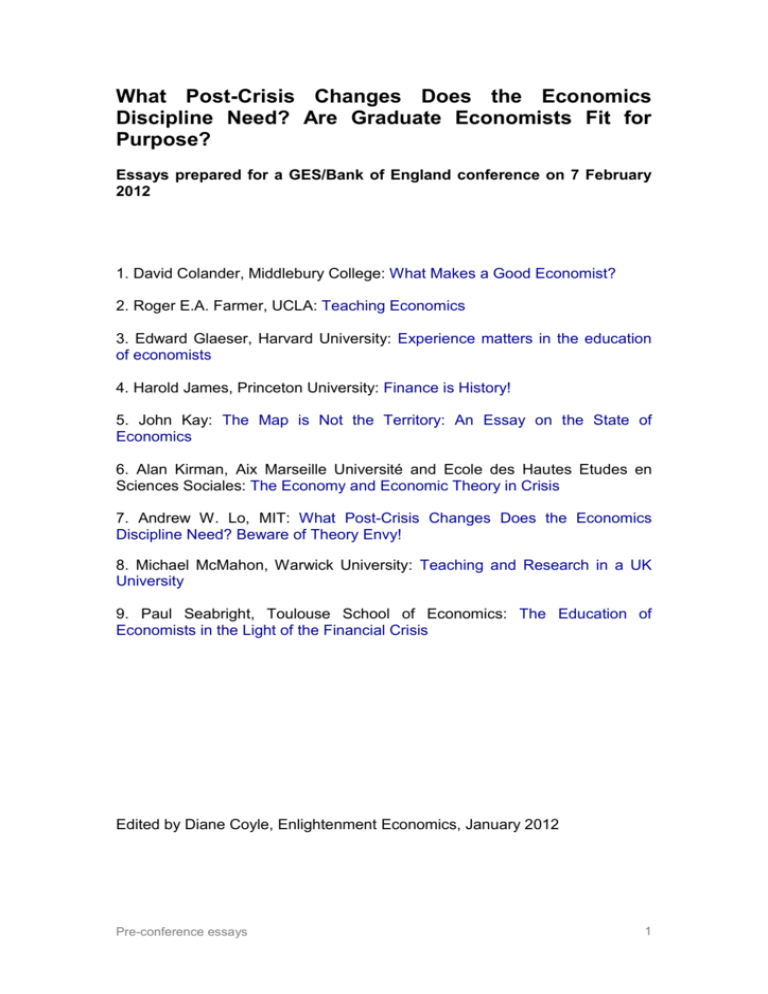

Enlightenment Economics

advertisement