Jane Spiro - Brookes Wiki

SEEING REFLECTION IN THE ROUND: LEARNING GOALS LOST IN

TRANSLATION

Jane Spiro

Westminster Institute of Education, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK

Jane Spiro, jspiro@brookes.ac.uk

, 01993-810629, 0787-6550-124.

Jane Spiro is Principal Lecturer running MA programmes at Oxford Brookes

University. Her previous posts include: leading teacher development programmes for

Mexican University teachers, Assistant Director of Studies at Pecs University,

Hungary; co-ordinator of the English Language Centre at Nottingham University; course manager of teacher training programmes in Switzerland, Poland and the

Netherlands. She is the author of Creative Poetry Writing (2004) and Storybuilding

(2007) with Oxford University Press and is a published poet and novelist with a recent PhD and research/teaching commitment to the connections between creative practitioner and educator.

Abstract

This paper explores the notion of 'reflection' central to United Kingdom (UK) higher education benchmarks of effective learning, and considers how this learning goal is perceived by domestic and international students. The study draws on the experience of students embarking on an MA in Education, with an explicit component of reflective development. It explores their understanding of reflection prior to this taught component, and again after it has been completed, and traces their changing perception of what reflection actually means and what it can contribute to their practice. Whilst this study is specific to a particular student group, the research invites us to consider how far perceptions change as an outcome of higher education study.

The study also causes us to review our assumptions about students from domestic and international backgrounds, and consider what is, or is not, valued in their experience of higher education.

Introduction

This paper explores the notion of 'reflection' central to United Kingdom (UK) higher education benchmarks of effective learning, and considers how this learning goal is

1

perceived by domestic and international students. For the purposes of the study, domestic students are defined as those whose pre-university education was in the UK and in the medium of English, whilst international students are those whose earlier education was outside the UK and, in the case of this study, not in the medium of

English. In exploring their view of reflection, we look at what is and is not 'lost in translation', and whether our expectations regarding 'reflection' are really transparent.

The study draws on the experience of students embarking on an MA in Education, with an explicit component of reflective development. It explores their understanding of reflection prior to this taught component, and again after it has been completed, and traces their changing perception of what reflection actually means and what it can contribute to their practice. In doing so it asks the following questions:

What were the differences in the way ‘reflection’ was perceived and experienced at the start of their study before explicit teaching, and by the end, after a one year teacher development programme?

Were there any differences in the way domestic and international students experienced this transition?

What are the implications of these findings for the HE educator?

Whilst this study is specific to a particular student group, the research questions invite us to consider how far perceptions change as an outcome of higher education study.

The study also causes us to review our assumptions about students from domestic and international backgrounds, and to consider what is, or is not, valued in their experience of higher education.

The Meaning of Reflection

In the past ten years, ‘reflection ’ as concept, practice and criteria for excellence, has entered the rhetoric of higher education. In 2009, 55 subject disciplines in the UK

Higher Education sector referred to ‘reflection ’

, or synonyms of reflection, within their subject benchmarks of graduate competence (QAA, n.d.). Broadly, their use of the term can be interpreted as “learning and developing through examining what we think” (Bolton, 2010, p. 13). This ‘learning and development’ is perceived by reflective practitioners as running alongside practice and leading to action, and entails an “acute focus upon what is happening at any time” (Bolton, 2010: 15). There is a

2

notion of reflection taking place before, during and after action, a continuous and ongoing process (Schon, 1983). This is frequently represented as a cycle, as in Kolb

(1984): experience leads to reflection, which leads to learning that can in turn be fed back into practice. Tripp, for example, explores the capacity of reflection to transform

‘critical incidents’ into learning opportunities after the event (Tripp, 1995); Wilson

(2008) traces the chronology of reflection to inform and prepare for future action.

Practice-based disciplines, such as nursing and teacher education have evolved typologies of reflection relevant to their own practitioners. In nursing education,

Hargreaves (2004) identifies three approaches she calls the cognitive, the professional competence, and the personal. A cognitive approach focuses on the development of critical thinking, the ‘professional competence’ model focuses on the improvement of practice whilst the ‘personal’ approach emphasises individual experience - a deeper understanding of personal values, and how these are expressed and lived through practice. In teacher education, Jay and Johnson (2002) evolved a different typology: descriptive, comparative and critical reflection. Their typology suggests a chronology in which the starting point is the “describing” of a problem, then “reframing” the problem “in the light of alternative views” (comparative reflection), and finally

“establishing a renewed perspective” (critical reflection) (p. 77). To some extent these levels map over Hargreaves’ approach, but omit the focus on the personal.

Entwistle’s (2009) cross-disciplinary study at Edinburgh University looked at the way different academics across subject disciplines interpreted the term ‘reflection’. Some saw reflection as the capacity to link learning and theory with real-life situations and contexts. (p. 59). Other disciplines regarded a critical and analytical approach to data as the core of reflection (Entwistle, 2009, p. 60). Trowler and Cooper (2002) recognized that there is a cluster of teaching and learning practices which are

“conditioned by a lecturer’s discipline” (p. 222). Thus, whilst reflection might be a term used across different subject disciplines, the legitimate objects of reflection vary between self, text, ideas, practice or the external world, depending on disciplinary standpoint.

The present study addressed the question of how students perceived ‘reflection’ prior to higher education study and after one year of MA-level teacher development. What

3

did they consider permissible and valuable as ‘objects of reflection’ before study, and how did this change after one year of teacher development? It also questions whether this emerged equally for both the domestic student and the international student.

The International Student and Higher Education

Literature concerning the international student in the English-speaking higher education academy has tended to focus on one of two perspectives: recruitment and retention issues (for example, Walker, 2010); and deficit models of the student in a second language culture, focusing on the extent of ‘difference’ between their needs and those of local students. Clark and Gieve (2006) explore the construction of

Chinese students as “lacking in the capacity for critical thinking”, attributed by their educators to cultural background (Singh, 2010, p. 37). This perception is the foundation for much of the literature about the international student. Tavakol and

Dennick (2010), for example, suggest there is still a perception that Asian medical students use rote learning in their studies, although this view of students with

Confucian cultures has been long debunked and deconstructed (Watkins and Biggs,

1966). There is a wide literature on the ‘special needs’ of international students, such as Yanyin and Yinan (2010) who identify academic writing as the most persistent challenge for Chinese students in Australian Universities.

Deficit models of international students are, however, problematic. Singh (2009;

2010) suggests that the western-educated lecturer is equally “ignorant” of the learning culture of Chinese students as vice versa, and that what both experience is not so much a knowledge deficit, as a knowledge mismatch. There are traditions of criticality within Confucian tradition which are simply not being enabled within a system that is ignorant of it. In addition, he offers a call to action to the HE educator, warning that deficit models of international students might offer the HE educator “an excuse for failing to teach them” (Singh, 2010, p. 33). His work focuses on the supervisor/student relationship, and the exploring of knowledge mismatches between these two.

The present study in contrast focuses on the synergies between the international and the domestic student, and their relationship with the privileged knowledge of the

4

lecturer. It questions whether the challenges of these two groups of learners are indeed distinct and different, and what the HE educator’s responsibilities might be as a result. Both groups of learners are increasingly, and across all subject disciplines, required to engage with the notion of ‘reflection’. Thus a clear definition of reflection is of equal importance to learners who are both familiar, and new, to the UK HE academy.

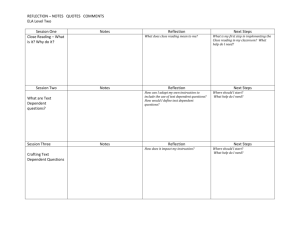

Description of the Research

The students in the study were all practicing teachers, in a range of different teaching contexts, subject specialisms and physical locations, as shown in the table below.

Table 1: Demography of students involved in developing reflective practice

FE HE TOTAL

International Columbia

(educated Poland, France, outside the Switzerland

UK)

Domestic

(educated inside the

UK)

TOTAL

India, Pakistan,

Brazil, Kuwait,

Korea, China,

Japan, Tai Wan,

Vietnam

Primary Secondary

2 10

ESOL ESOL

10

Literacy,

Numeracy

Special needs,

12

7

Religious

Education

Maths,

Modern

Languages

Music

English,

Literature,

Biology

17

1

5

English

Literature

ESOL,

Marketing,

Psychology

Catering,

Critical

Thinking,

6

2

ESOL

1

Health and

Social

Care,

ESOL

3

15

23

38

5

As Table 1 shows, a wide number of variables are in place, including differences in disciplinary background, teaching sector and context, learning background and first language of study. The common element for all, however, is their commitment to acquiring further qualifications as a teacher and doing this within the context of a UK

HE institution, with ‘reflective practice’ defined as the first threshold programme.

The students were invited to write an opening statement at the start of their studies which addressed the three aspects of reflective development enshrined in Hargreaves’ typology (2004): questions relating to their skills as critical thinkers (see questions iii, iv, v below); questions relating to their professional experience and practice

(questions vi, vii); and questions relating to their personal values and beliefs

(questions i and ii).

The opening statement invites you to reflect on the motives and experiences which have led you to MA study as a teacher, and the specific challenges which you envisage in your progression to teacher:researcher. Some of the questions we would like you to consider in writing your statement include: i) What were the motives and experiences which led to my choice of the teaching profession? ii) What were the motives and experiences which led me towards MA study? iii) What has been my experience of study in the past? What have I found inspiring? What kinds of study/learning have influenced me most? What have I found difficult and challenging? iv) What are the specific strengths and knowledge areas which I bring to MA study? v) What are the specific areas which I am concerned about in MA study? Which

‘gaps’ am I hoping to fill in my skills/knowledge/experience through MA study? vi) Where am I now as a teacher and what are my main concerns and challenges? vii) How can the MA help me in these areas?

This opening statement was written without reference to any supporting literature about reflection, and without any further explicit support or direction. It was then

6

kept and stored, to be returned to at the end of a year of development.

This year of development mapped over the three phases in the Hargreaves model: firstly, explicit development of critical thinking, through analysis of critical articles, linguistic analysis of critical discourse, writing and editing of critical reviews; secondly, development of professional expertise through action research, analysis of teaching events, classroom observation and evaluation, and thirdly, exploration of personal values through analysis of critical incidents, and formulation of action plans for personal development.

After one year, students were invited to return to their opening statements, and note the changes and developments which had occurred.

Review your Opening Statement and reflect on ways you might have changed or developed since you wrote this.

Consider the impact of these changes on your own skills as a reflective practitioner and a reflective researcher.

How might you draw on this experience in your own writing, reading, and practice?

These student records were anonymised on completion, and names replaced with an identity number which differentiated between domestic and international students: DS for ‘domestic student’, defined as students who had been educated in the UK at primary and/or secondary stages; IS for ‘international student’ whose earlier education had been outside the UK. Students identified also if English was/was not their mother tongue or language in which they were educated before this study.

Methodology

The data was gathered longitudinally during the course of an academic year of study, and from two cohorts in two consecutive years. The opening statement was written in the first two weeks of study in each case (October); and the closing statement was written up to 6 weeks after study was completed at the end of the academic year

(May).

7

As noted above, the cycle of reflection students participated in through the academic year included explicit focus on the three approaches identified by Hargreaves (2004): firstly, reflection as the development of critical thinking as a teacher/researcher preparing to engage in scholarly debate with their community; secondly, reflection as leading to professional competence as a teacher/practitioner; and thirdly, reflection as an examination of personal beliefs and values.

An interpretative approach was adopted in analyzing the two sets of statements that emerged. It was understood that the data could be interpreted in a number of ways, depending on whether the researcher focused on surface linguistic features (such as the use or otherwise of the first person pronoun); inference and connotation (such as whether or not statements were made with a positive, negative, or neutral linguistic

‘colouring’); frequency (such as how often certain terms or ideas were referred to). In the event, each of these three approaches were adopted in analyzing the data.

Frequency of themes was noted; as well as the way in which the writers did, or did not, refer to themselves through the use of the first person pronoun or other linguistic strategies.

In addition the data was analysed in two stages. Firstly opening and closing logs were analysed independently of one another, and themes were identified which were represented in eight or more of the entries. A second stage of analysis involved splitting the data between those students who had identified themselves as international (IS), and those who had identified themselves as domestic students (DS), and noting how far these student groups echoed or differed from one another. It was possible, through these enquiries, to identify specific challenges and confusions experienced by students; ways in which reflection had (or had not) become internalized as part of their learning; if and how the concerns and perceptions of international and domestic students differed.

Findings

Opening statements

Reflection as personal development: clarifying beliefs and values

8

Evident in this first iteration of reflective writing, was the students’ own struggle with the issue of whether ‘reflection’ invited them to focus on self and turn inwards, or to focus on others and turn outwards. Some hoped that reflection would help them clarify and confirm personal beliefs: “I found myself struggling to articulate my principles about how young children learn. Later, I found myself questioning my own beliefs.” (DS4). “I realize I have never prioritized personal reflection – I feel that studying for the MA—is one way in which I am ‘taking charge’ of my professional development “ (DS1). For many, this focus on self represented the difference between the kind of learning they had been involved in previously, and the challenges of postgraduate study.

Reflection as a basis for criticality: focus on the other

Reflection is also articulated as outward-facing, offering the opportunity to contribute to professional debate and help to shape it. In this sense, the student-teachers adopt the view of reflection as “located in the political and social structures which are increasingly hemming professionals in.” (Bolton, 2010, p.11). Many revealed the high value attached to this different way of learning. “I currently accept what is given to me from management as the right or correct thing to do. I hope that doing the MA will open my eyes to questioning what is given to me.” (DS2). “I would like reflection to help me develop my abilities to evaluate – policies and how they affect students, teachers and management staff” (DS23).

Reflection as a basis for developing practice: focus on professional role and skills

A third set of responses looked towards reflection for resolving professional problems and improving practice. “I need to learn to use my reflection to lead to more definitive action” (IS7), with occasional reference to specific skills such as

“improving my questioning techniques” (IS21) through reflection. Others had broader hopes for their overall development as educators: “I am keen to extend my profession development and become the best teacher I can be” (DS24). “I would be interested to explore the boundaries between allowing freedom of opinion and preventing prejudice and intolerance”(IS42) ; “my personal target is to provide a learning environment that is full of challenge” (DS3). What many of these accounts shared was the belief that reflection could ‘tease out’ areas of challenge and lead to self-improvement. One student had a notion of reflection as an ‘inner coach’:

9

As a young child and through until my late twenties I was heavily involved with a sport and had to reflect on my own performance. This reflective period was encouraged by my coaches and has allowed me the opportunity to analyse where any mistakes in technique or execution have arisen – make any adjustments necessary (DS22).

In analyzing these data sets, it is interesting to note that the domestic students more frequently referred to the ‘outward-facing’ aspects of reflection, possibly because they were studying within the professional context to which they wished to contribute.

The international students were represented most frequently within the third theme – the role of reflection for the improving of practice and professional skills. Several identified this latter as one of the prime motives for embarking on a teacher programme, and for many the importance of improving their English language skills was integral to their professional development.

Closing statements

The closing logs, however, revealed many more categories for discussion, and the themes suggested above were articulated with far more precision and detail.

Compared to the three key areas identified above, eight emerged from the closing data, regarding what had been learnt from reflection:

Clarifying beliefs and arriving at personal insights

The student-teachers identified several ways in which reflective development had given them insights into their own responses, practice and values. For example, one writes that he had found peer evaluation difficult to accept, but in the course of reflection came to appreciate its value and “accept peer comments in the way they are intended: helping refine one’s work in the pursuit of professionalism.”(DS32).

Another student-teacher recognized that when he had strongly held views, it made him less rather than more communicative: “I’m afraid I became so passionate that my view was absolute that it blinded me of other views.” (DS5). Personal beliefs became clarified for some: one student-teacher came to see, for example, that “selfesteem comes from being rigorous about the subject” (DS27), rather than from

‘praise’ or ‘support’ that emerged from a broad well-being agenda.

10

Reassessing the meaning and value of criticality

For many, the process of reflection served also to clarify the meaning of ‘critical’.

This was an area most frequently mentioned by international students. Several echoed the realization that “criticality is not about being negative but about asking questions” (IS14). “ I had completely misunderstood the word “critical”. I thought I had to find all the wrong things” (IS18). As well as being more balanced in approach, there was an understanding that ‘criticality’ also involved being more actively engaged with texts, rather than absorbing either teacher or author voice without question.

I have started to understand the notion of “being critical in academic enquiry”(Wallace and Poulson, 2003, p5 ) and learn to be critical in my learning instead of being a passive receiver as before. (IS19).

Some were clear that this was a consistent message from all tutors, and its repetition often became wearying: “throughout the course all our lecturers have questioned us when we make truth claims. At first this could be frustrating, but over time I can really see why it is so important.” (DS16). Many saw the skill as providing a practical service to them as professionals: “I continue to try and develop critical and independent thought as a basis for advanced educational practice” (DS6) .

Revisiting assumptions

The process of reflection also enabled student-teachers to reach moments of enlightenment – what one participant called ‘Eureka moments’. Some of these related to specific research skills, for example, the realization from a science-based student that in educational research, practice could be a focus of study, “My tutor’s explanation that educational research included ‘gathering insights from real experience’ was just the encouragement I needed to continue the journey” (DS10).

Another ‘Eureka moment’ for a student-teacher included the review of lifelong-held perceptions, “Prior to starting this MA I thought that school was education. Now, I think differently” (IS27). One student-teacher working in a second language context, was forced to reconsider his assumptions about his students, “My first experience of learning to question my beliefs came – when I was reminded I should ‘take care not to

11

assume a deficit model’ in the Taiwanese education system and encouraged to try to understand their underlying theory of learning and teaching” (DS16).

For others, the assumptions revisited were those related to the reflective process itself.

Several noted that they saw reflective skills as shining a light on newly identified aspects of a task: from solutions to problems, “ I had not even considered reflecting on an initial problem – I had only thought about reflecting on a solution” (DS39), and from process to outcomes: “I spend more time now looking at the outcome rather than how I’m going to complete the task” (DS12). What emerges is not that reflection offers a yardstick of practice, but that it offers new options not formerly considered, and thus different for each reflective practitioner.

Understanding the role of self in research

Several student-teachers, after one year of study and reflection, were able to understand more clearly where the ‘I’ persona fitted in educational research. “ It has been a revelation to understand that a researcher’s own values, experiences and interest in the research, properly exposed, is an accepted and valuable contribution to the reported findings” (DS27).

Specifically, too, student-teachers came to appreciate the way in which one might establish a personal viewpoint within, and in response, to the professional/academic literature. This was expressed by one student as bridging the gap between “school and the professional thought which I always felt should have better informed those actions” (DS16).

Developing learning skills and strategies

Through reflection, student-teachers also record development both in academic reading and academic writing. Reading proved a challenge for all, but was marginally more often referred to by international students. Having said this, the concerns were parallel; they included the challenges of dealing with long bibliographies, and the process of learning to be selective and critical in reading. One writes, “I always read very slowly and thought every part was important to get the idea. Thus I couldn’t get the main idea quickly. In this module, I learned how to read academically. That is to say, I can read selectively”(IS17). Another found that, with these enhanced skills of

12

selection, the reading lists ceased to be so daunting, “I have been forced to return to the reading lists, and much to my surprise have found a form of consolation in some of them” (DS39)

In terms of writing, the relationship between writing, reflection and memory was raised by one international student, “when I was starting to think as a reflective practitioner, my reflections were all from memory. However, over the course of this module I have kept a written diary of my reflections, which has helped me to make planned changes to my practice” (DS11). Grappling with appropriate register was noted by all students, but in the case of one international student, the challenges were explained with reference to differences in teaching style:

I definitely learnt to keep more objective and less passionate when writing and criticizing, because emotional reaction is not academic. Perhaps this was a natural reaction to my previous academic learning experience, which had been too rigid and determined by official critics (IS8).

Recognising the value of independent learning

One issue widely noted by both home and international student data was the challenge of independent learning as a core approach in the HE sector, “the open-endedness is quite scary at first – but seeing how much I learn from that has been a revelation”

(DS10).

This student-teacher continues by exploring the differences between facilitating independent learning as a teacher, and experiencing it as a student: as I have begun to engage with the diverse, inclusive, deeper levels of questioning and discussion, I have experienced a much better way of learning

– one which, ironically, I have practiced for years with my pupils (DS10).

In addition, student-teachers record the transition from undergraduate to postgraduate study: in returning to University, I assumed it would be as I remember undergraduate study, where most questions had a definite answer and my job was to find it.

Masters level study is far from that in pedagogy and, initially, I found that quite difficult” (DS20).

13

Student-teachers from China, Ghana and Tai Wan record a similar sense of surprise and challenge in making this transition from learning patterns in their earlier studies, and in the UK HE academy.

Two important outcomes emerged from the strategies, skills and ‘Eureka moments’ described above: firstly, an increase in self-esteem mentioned by the group across the whole cohort; and secondly, in the case of some of the participants, very specific

‘calls to action’ leading to professional change, from major career changes to more surface changes connected with classroom practice.

Developing self-esteem

The student-teachers noted the self-esteem emerging from the permission to place the self within the scope of research enquiry, “realizing you have just as much to contribute from your own professional perspective” (IS14). In addition, the process of clarifying beliefs allowed one student-teacher to develop her “confidence and thinking and . . . concentrate on what is important to me”. (DS31). In the process of reviewing their practice, one comments that she “had interpersonal skills I had not previously acknowledged. This has led to a greater feeling of self-confidence which others recognize and I am now finding that school leaders and managers are beginning to ask me for help and guidance” (DS12). Another realized she had “a broadness of vision that I didn’t fully appreciate” (DS15).

Reflection leading to action

Several of the participants record a complete cycle from reflection to action: one moved from private to state education: another applied for a Deputy Headship successfully; another, who had failed to win a Head leadership role, came to understand what needed to be done to achieve this. Several made specific changes to their practice, “I have also begun to provide more in-depth feedback to candidates when marking examination papers” (DS10). Another began “running workshops for colleagues” (DS24), and a further participant “found the e-learning component so useful that I have been inspired to create a wiki for my senior school classes” (DS1).

In exploring the data, a further categorization was made to differentiate domestic students and international students, and identify any patterns of similarity and

14

difference which emerged. As suggested above, there were some slight differences in emphasis with reference to writing and reading skills, but broadly the issues and concerns were shared by both groups. However, two issues were mentioned by international students, over and above those listed above. They were:

the challenge of different teaching styles between domestic and UK contexts

the challenge of studying in a second language

The challenge of different teaching styles between home and UK contexts

The international students specifically identified the problems of transition from one learning culture to another. One writes, “in Ghana … there is less emphasis on independent study and more focus on developing the information provided by lecturers in their sessions. . . I experience a great deal of difficulty with the transition that was required to be made in a very short period of time” (IS34). We have seen that the issue of independent study was also noted by students studying in their home contexts. For some of these, the difficulty was perceived as the transition between undergraduate and postgraduate study. Another student writes, the teaching style ...is completely different from that of China. In China, teachers are speakers while students are listeners. There’s little classroom interaction so we could be a little bit lazy. I didn’t even listen to the teacher if I was not interested in the lecture. In MA class, I need to be attentive all the time and do a lot of preparation work in order to keep up with the tutors. So I have to change my teacher-dependent study habit and learn how to study by myself

(IS18).

The challenge of studying in a second language

We have seen above that domestic students noted the challenge of academic writing, of containing their emotional reactions and negotiating the research literature in their writing. The student-teachers for whom English was not a mother tongue had stronger concerns about their language skills, not only in writing, but also in listening and speaking. “Before I came to this university, I wondered whether I could understand the lecture and finish my study successfully since I didn’t think my

English is good enough” (IS18). They may well have started the programme with less confidence than their native speaking counterparts – even though the outcomes might have been equally successful, “the first year on the Master’s degree course has given

15

me the confidence with my increased knowledge of academic writing in terms of being better able to correctly express my views to other professionals” (IS28).

Discussion

Was there a difference in the way ‘reflection’ was perceived and experienced by domestic and international students?

Many of the challenges and confusions that arise from our expectations of reflective writing are shared by both domestic and international students. Both groups of student found the notion of criticality confusing at the start, and gradually resolved this in the course of a year of study. Both groups needed to hone their writing skills to be appropriate in register and sufficiently well-informed in content. Both groups needed to renegotiate where the ‘I’ persona sat within reflective and academic writing, and within educational research. What emerges as different is that domestic students saw the challenge arising from the transition into an academic, or a different academic, culture whilst international students viewed this challenge as a component of their cultural transition from one country to another. In addition, several of the international students believed that domestic students were able to respond to expectations more readily than themselves.

As higher education teachers, it is interesting for us to note that, in effect, the challenge is equal for all student groups, mature and traditional, domestic or international, L1 or L2 English speakers. The implication of this is that we might focus, not on the differences between students, or the ‘special needs’ of the international student, but on the similarities. This is not a new understanding,

Montgomery (2010) found this too, in her research into students in formal and informal settings, “Many of the issues facing the international student group are those that face all students, and indeed all of us as people” (p. 125). What is specific for the teacher drawing on reflection as an expectation in student writing, is that there is an equal need to clarify certain questions for all students: where does acceptable reflective writing sit, along a spectrum from ‘self’-focused using the I persona, to

‘criticality about the other’? What is the appropriate balance between these? In the case of the ‘self’ forming a centre of reflective writing, what are the indicators of

16

rigour? What are the requirements to meet writing or content conventions? In other words, how far does the ‘self-focused’ content of reflective writing offer license to develop and write within one’s own rules?

What are the implications of these findings for the HE educator?

Emerging from this study are several key considerations for the HE educator.

Supporting and clarifying the academic culture for the international student will be of equal value and importance for the domestic student. There appeared to be more equivalence in their needs than differences. In particular, establishing a subject disciplinary culture requires a clear explanation of that culture, whoever the student.

This includes clarity about different approaches to ‘reflective practice’, the ideologies behind these approaches, and the approach embedded in the discipline. In addition, when tutors themselves consider the teaching and framing of reflective practice, it would be of value for them to consider how these relate to purposes and learning goals. The reflective training of teachers, for example, might have the multiple purposes of improving practice, offering teachers the chance to contribute to professional debate, and enhancing personal growth and self-knowledge. These, however, presuppose three different learning outcomes, discourses and literature bases, and need to be framed as such.

The study also offers a response to the notion of difference between the international and domestic student. These findings suggest that the mismatch between the privileged knowledge of the educator, and that of the learner/student, is in fact experienced equally by domestic as well as international students. Thus, the failure to teach international students effectively leads to failure to teach the domestic student, and conversely, understanding the needs of the former fully involves understanding the needs of the latter (Carroll and Ryan, 2005).

Conclusion

What emerges from the student data is that the process of reflection, however it is framed by educators themselves, was perceived by these student-teachers as a core and important aspect of their learning, if not synonymous with learning. Their

17

accounts in the closing statement emerged as rich and complex, and offer to the researcher a number of new ways of categorizing the ‘reflection’ dilemma. In addition the data shows that international and domestic students have parallel challenges, although they may not perceive this to be the case. As HE educators we can be aware that students will find for themselves what is meaningful within the spectrum of possible interpretations of ‘reflection’. We might support them in doing this, by being explicit about the range of meanings, and the potential conflicts between them.

In addition it helps us as HE educators, to be in dialogue with our colleagues across disciplines, to deconstruct assumptions about the reflective paradigm, its focus and outcomes, and how these might differ from subject to subject. In recognizing these differences, we might also see the assumptions that students bring to the learning process, and the assumptions which we ourselves bring to the learning/teaching process.

References

Bolton, G. (2010). Reflective Practice (3 rd

edition). London: Sage.

Carroll, J. & Ryan, J. (2005). Teaching international students. Improving learning for all . London: Routledge.

Clark, R. & Gieve, S. (2006). On the discursive construction of the ‘Chinese learner’.

Language, Culture and Curriculum , 19 (1), 54 – 73.

Entwistle, N. (2009). Teaching for Understanding at University: Deep Approaches and Distinctive Ways of Thinking.

Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hargreaves, J. (2004). So how do you feel about that? Assessing reflective practice.

Nurse Education Today , 24 , 196- 201.

Jay, J. K. and Johnson, K. L. (2002). Capturing complexity: a typology of reflective practice for teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18, 73 – 85

Kolb, D.A. (1984). Experiential Learning . London: Prentice Hall.

Montgomery, C. (2010). Understanding the International Student Experience .

Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

QAA (n.d.) Honours Degree Benchmark Statements. Retrieved November 21, 2010, from http://www.qaa.ac.uk/academicinfrastructure/benchmark/honours

Schon, D. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action .

New York: Basic Books.

18

Singh, M. (2009). Using Chinese knowledge in internationalizing research education:

Jacques Rancière, an ignorant supervisor and doctoral students from China.

Globalisation, Society and Education , 7 (2), 185-201.

Singh, M. (2010). Connecting intellectual projects in China and Australia: Bradley’s international student-migrants, Bourdieu and productive ignorance. Australian

Journal of Education, 54 (1), 31- 45.

Tavakol, M. and Dennick, R. (2010). Are Asian international medical students just rote learners? Advances in Health Sciences Education, 15 (3), 369-377.

Tripp, D. (1995). Critical Incidents in Teaching . London: Routledge.

Trowler, P. and Cooper, A. (2002). Teaching and Learning Regimes: Implicit theories and recurrent practices in the enhancement of teaching and learning through educational development programmes. Higher Education Research and Development ,

21 (3), 221-240.

Walker, P. (2010). Guests and hosts -- the global market in international higher education: Reflections on the Japan-UK axis in study abroad. Journal of Research in

International Education, 9 (2),168-184.

Wallace, M. & Poulson, L. (2003). Learning to read critically in educational leadership and management. London: Sage.

Watkins, D. & Biggs. J. (eds.) (1966). The Chinese Learner: cultural, psychological and contextual influences . Victoria: Australian Council for Education Research.

Wilson, J.P. (2008). Reflecting-on-the-future: a chronological consideration of reflective practice. Reflective Practice, 9 (2), 177- 184.

Yanyin, Z. and Yinan, M. (2010). Another Look at the Language Difficulties of

International Students. Journal o f Studies in International Education , 14(4), 371-388.

19