unit plan - Achievement First

advertisement

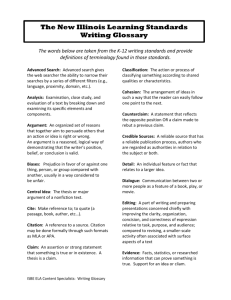

8th Grade, Unit 9: Literature and Writing Introduction, Overview, Assessment, Aims, and Calendar Table of Contents Literature class and writing class unit introductions and overviews Unit Assessments, Summative Assessment Aims for literature class and writing class Unit calendars for literature and writing class 8th Grade Literature Unit 9 Overview – A key focus of the Common Core State Standards is research—both short and extended research projects. This unit is an extended research project. Scholars will read Chew on This by Eric Schlosser and Charles Wilson as their primary text. Scholars will generate and answer questions on a topic related to this and other texts, annotate purposefully in service of their questions, analyze an author’s claim, determine the validity/usefulness of a text, and develop a research proposal. The aims and focus standards guide you in working through a hierarchy of knowledge: from comprehension and application to analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. The practice of annotation will reflect this hierarchy of reading. Scholars will generate guiding questions about the author’s purpose and the overarching themes of the book and its chapters and annotate based on those guiding questions. They will move from marginal notes on ideas to notes on the intersections between ideas and the presentation of those ideas, ultimately analyzing how the author uses structure, tone, and style to develop central themes and motifs. Scholars will first practice identifying key ideas and supporting details, relevant and irrelevant information, and fact and opinion in informational texts. They will then move from an understanding of the ideas in the texts to an exploration of the ways in which their understanding is affected by the presentation of the ideas. Chew on This is a highly rhetorical text, and should be approached as such from Day 1. A quick preview of this book’s cover, layout, blurbs, visuals, author biographies, Table of Contents, and index reveals a clear purpose, tone, and audience. The ability to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant information and facts and opinions in this text is inextricably intertwined with the ability to dissect rhetoric. While scholars will explore rhetoric in more detail in 9th grade, today's 8th graders engage with a complex web of rhetoric by the minute. The basic assumptions of the primary text--that 8th graders can critically engage with media, that they can counter cultural hegemony when equipped with the information to make educated choices, should be embedded in your lessons, as should the implication of standards RI.8.6, RI.8.8, RI.8.9, which focus on author’s point of view, arguments, claims, evidence, and persuasive advocacy, thereby acknowledging that “informational” nonfiction is persuasive nonfiction. Articles from the bundle are interspersed with Chew on This. These articles are largely an ideological extension of Chew on This. Though the bundle articles do not offer alternative views, they do address some of the complexities of changing America’s food culture. They are perhaps most useful in offering less dense (i.e., lower reading level) side notes about how food reform is playing out in America. If you can find articles of an appropriate reading level that offer alternative viewpoints, arguing that the fast food industry has stimulated the economy and created jobs or that advertising regulation has not changed consumer behavior, for example, these would be useful in targeting standard RI.8.9. Likewise, having scholars evaluate the claims in the packet the NRA created for schools reading Chew on This would be an interesting way to hit standards RI.8.8 and RI.8.9. In this unit, scholars come to understand that rhetoric includes appeals to an audience’s reason, emotion, and ethics, and that these appeals are made through tone, structure, and style, which they have studied in previous units. Gradually, they move from identifying to evaluating the rhetorical techniques informational authors use to engage and persuade the reader, including visuals, facts, statistics, and patterns of writing. If the dissection of rhetoric builds on the skills scholars use in their everyday lives, the dissection of patterns of writing builds on scholars’ previous studies of fiction, narrative nonfiction, and biography, in particular the use of narratives, true and not, to instruct, engage, and persuade. In this unit, scholars come to understand how these modes of presentation are used to shape information. The better they understand the effect that presentation has upon them as readers, the better they can evaluate the validity of the information presented, and ultimately manipulate modes of presentation in their own research-based writing in Unit 10. The understanding that all information comes from a source and thus all information must be weighed against other information will be crucial as students begin their research proposals at the end of this unit. In creating their own research-based texts in Unit 10, scholars will move from investigating rhetorical techniques in the work of published informational authors to manipulating them in their own writing. This unit aims to make scholars more informed choosers, not just in the realm of research, but in everyday life. Its progression supports a transition from passive consumption to active shaping of information, a transition essential to the survival of the individual in our postmodern media-saturated world. 8th Grade Bundles: https://afnet.achievementfirst.org/Curriculum/Shared%20Documents/Forms/All%20Docs.aspx?RootFolder=%2fCurriculum%2fShared%20Docum ents%2fMiddle%20School%2fLiterature%2fBook%5fLists%5fText%5fSamples%2fText%5fPairings%2fBooklists%2eBundle%5fsheets&FolderCTID= &View=%7bFCB1F1C3%2d568F%2d4FB8%2dA34B%2dE57753D4E174%7d RI.8.2 Determine a central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text, including its relationship to supporting ideas, provide an objective summary of the text. RI.8.6 Determine an author's point of view or purpose in a text and analyze how the author acknowledges and responds to conflicting evidence or viewpoints. RI.8.8 Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, assessing whether the reasoning is sound and the evidence is relevant and sufficient; recognize when irrelevant evidence is introduced. RI.8.9 Analyze a case in which two or more texts provide conflicting information on the same topic and identify where the texts disagree on matters of fact or interpretation Use their experience and their knowledge of language and logic, as well as culture, to think analytically, address problems creatively, and advocate persuasively. Essential Questions: TEXT: Can individuals change society by making smarter choices? SKILL: How do we critically engage with information? Enduring Understandings: Text: 1. Because informational nonfiction authors manipulate research to persuade the reader, all information must be approached critically.2. Critically engaging with information involves evaluating a source’s biases, assessing the validity of the information, and dissecting its presentation. 3. Research involves evaluating a variety of sources representing different perspectives to draw informed conclusions. Skill: 1. Informational nonfiction authors use rhetoric to present information in ways that appeal to readers’ reason, ethics, and emotions. 2. Informational nonfiction writers incorporate the techniques of fiction writers, narrative nonfiction writers, biographers, and marketers to educate, engage, and persuade their readers. Dissecting these rhetorical techniques enables a reader to better evaluate the validity of the information presented. 3. Developing a research proposal involves selecting, reading, and evaluating a variety of reliable sources that reflect different perspectives on a subject. Unit Goals Readers will: generate and answer questions on a topic related to the class text, annotate purposefully in service of their questions, analyze an author’s claim, and determine the validity/usefulness of a text. Develop a research proposal Grade 8, Writing Unit 9 Overview – In writing class, this unit serves a dual purpose: 1. To write a culminating literary analysis essay on complete book 2. To write a research proposal in preparation for their final research paper As the year comes to a close, the literary essay and research paper serve as their culminating writing experiences in middle school, asking students to synthesize skills honed over the course of the year. Though the unit has a dual purpose, time is not split in half. The vast majority of instructional time should focus on the final literary essay. Students should vet their research topic during this time so they are set up for success in unit ten, but it is imperative to note that the research proposal is not the major focus in this unit. To ensure that the research proposal receives the appropriate amount of attention necessary, we recommend coordinating with your reading teacher. Students are exploring informational non-fiction in reading class and reading teachers are primed to brainstorm and explore potential topics related to the theme of unit nine. If you do not plan closely with your coteacher, it will be essential to meet in order to create a plan for completion of the research proposal. In writing class, the underlying outcome of this unit is that scholars will be able to write a literary essay about issues that came up in the historical fiction novel read during Unit 6. Please note, if you and your students already wrote a literary essay for unit six, feel free to select a different text. However, it is essential that the text is a book that the students completed. It is important that students are asked to write about a book as a whole and not a short story, as it is developmentally appropriate that students are asked to navigate an entire novel and synthesize ideas about a book as a whole. In their literary essays, students will include: a clear and focused thesis statement that is not only defensible and accurately stated but is complex enough to support sub-arguments and also drive every idea in the paper, body paragraphs that incorporate topic sentences that are assertions and present sub-arguments that are directly relevant to the thesis, paraphrased and direct text evidence that is directly relevant to the sub-argument, an analysis and interpretation of the meaning of text evidence, transitions words, phrases, and clauses that create cohesion among claims, interpretations, and evidence chunks, and a logical conclusion that follows from and supports the thesis. As students begin the transition towards high school, it is recommended that they are given the appropriate amount of academic independence in this unit. This will be the fourth unit focused on literary response this year and students were exposed to the skills enough that most scholars should be able to flow through the writing process with limited support. To this end, you might wish to reach out to your students’ future 9th grade composition teacher to find potential areas for alignment. Aligning the process or expectations will simulate future conditions and go a long way to easing their transition into high school. There are sixteen aims in this unit and pace must be maintained to ensure ample time is left for unit ten. Italicized standards need to be spiraled into every unit. Writing Standards W.8.1 Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence. W.8.1a Introduce claim(s), acknowledge and distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and organize the reasons and evidence logically. W.8.1b Support claim(s) with logical reasoning and relevant evidence, using accurate, credible sources and demonstrating an understanding of the topic or text. W.8.1c Use words, phrases, and clauses to create cohesion and clarify the relationships among claim(s), counterclaims, reasons, and evidence. W.8.1d Establish and maintain a formal style W.8.1e Provide a concluding statement or section that follows from and supports the argument presented. W.8.4 Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience. W.8.5 With some guidance and support from peers and adults, develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach, focusing on how well purpose and audience have been addressed. W.8.6 Use technology, including the Internet, to produce and publish writing and present the relationships between information and ideas efficiently as well as to interact and collaborate with others. W.8.9a Apply grade 8 Reading standards to literature (e.g., “Analyze how a modern work of fiction draws on themes, patterns of events, or character types from myths, traditional stories, or religious works such as the Bible, including describing how the material is rendered new”). W.8.10 Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of discipline specific tasks, purposes, and audiences. Language Standards L.8.2b Use an ellipsis to indicate an omission. L.7.1c Place phrases and clauses within a sentence, recognizing and correcting misplaced and dangling modifiers. L.3.1f Use subject verb and pronoun antecedent agreement. L.8.2c Spell correctly grade appropriate words. Essential Questions: What is the purpose of writing literary analysis? How do we explore new ideas while writing (write to learn) but still keep a clear focus? What constitutes a high-quality thesis statement? How do I use the writing techniques I am learning to help me better comprehend, think about, and analyze the literature texts? Enduring Understandings: Literary analysis allows us to have a say in creating meaning out of a text. This writing mode values our opinions about literature. While scholars are learning to write and hone their craft, they also need to understand that writers develop new ideas while writing, i.e. they write to learn. A superb thesis statement provides the reader with the author and title, as well as with your opinion/claim about the text at hand. What we notice as interesting about a literary work could be the seed for a literary analysis essay, and with multiple re-reads of that work, we will be able to judge the best evidence for each point. Unit Goals Writers will be able to write a literary essay about the protagonist in the historical fiction novel read during Unit 6. In their literary essays, they will include: a clear and focused thesis statement that is not only defensible and accurately stated but is complex enough to support sub-arguments and also drives every idea in the paper , body paragraphs that incorporate topic sentences that are assertions and present sub-arguments that are directly relevant to the thesis, paraphrased and direct text evidence that is directly relevant to the sub-argument, an analysis and interpretation of the meaning of text evidence, transitions words, phases, and clauses that create cohesion among claims, interpretations, and evidence chunks, and a logical conclusion that follows from and supports the thesis. *Research Proposal – During this unit, students should submit a research proposal based on their reading in literature class to their writing teacher. The writing teacher should approve all topics before the start of the next unit. Literature Class Primary Aims Reading Aims Students will be able to: 1. Make predictions and formulate questions about the author’s purpose by previewing the text. 2. Annotate text to emphasize key ideas and supporting details. 3. Distinguish between relevant and irrelevant information in informational text. 4. Distinguish between fact and opinion to determine an author’s position. 5. Identify rhetoric as the techniques an author uses to engage and persuade the reader. 6. Analyze how two or more authors writing about the same topic use different evidence to inform about that topic. 7. Evaluate informational nonfiction writers’ use of visuals, facts, statistics, and anecdotes as evidence for their arguments. 8. Compare and contrast the organization of information about a similar topic from a variety of sources. 9. Identify and analyze how an author uses narration, description, and exemplification patterns to develop a central argument. 10. Identify and evaluate conflicting information in two nonfiction texts through comparison. 11. Analyze key ideas across multiple texts and formulate judgments about which text(s) presents the most useful information. 12. Use rhetorical techniques to persuade readers of a viewpoint. Secondary Skills to be Spiraled into Literature Lessons Secondary Skills for Research Unit, grade 8 1.) Secondary Skills: --Review how to use an index to locate information in an informational text. --Make predictions about a nonfiction book’s purpose, tone, and audience based on cover, layout, blurbs, visuals, author biographies, Table of Contents, chapters, and Index. 3.) Secondary Skills: --Nonfiction narratives and narrative elements such as description are often used to engage, instruct, and persuade. 4.) Secondary Skills: --The techniques a nonfiction author uses to persuade his or her readers are used in advertising, too. --Determine the meaning of words with content-specific definitions through context and/or use of a glossary.* (marketing/branding terms) 5.) Secondary Skills: --Determine an author’s underlying opinion in informational text and the ways in which (s)he attempts to shape readers’ thinking. --Distinguish between fact and opinion in informational texts. 7.) Secondary Skills: --Identify anecdotes as a narrative pattern of writing. 8.) Secondary skills: --Recognize that a biography is the story of an individual’s life, written by someone else, and thus a type of narration. --Analyze how a nonfiction author uses a biography to convey his or her opinion about society. 9 Writing Class Aims 1. Develop an idea, topic, or basic claim about the protagonist of the historical fiction novel read during unit 6. 2. Annotate the text looking for sections or specific parts that will help develop their claims. 3. Locate specific and relevant evidence that supports their idea and will help develop their thesis. 4. Revise their earlier idea by writing a clear and focused thesis statement that is not only defensible and accurately stated but is complex enough to support sub-arguments 5. Select the best evidence that supports their thesis. 6. Plan the body paragraphs by listing sub-arguments and evidence. 7. Narrow the scope of the essay by eliminating sub-arguments and evidence that are not driven by the thesis. 8. Draft the essay and incorporate analysis and interpretation of the meaning of text evidence. 9. Revise in order to ensure that indirectly cited evidence is paraphrased. 10. Revise in order to ensure that direct quotes are incorporated into other ideas and sentences. 11. Revise in order to ensure that every idea presented can be linked back to the thesis statement. 12. Revise in order to ensure that transition words, phases, and clauses that create cohesion among claims, interpretations, and evidence chunks. 13. Craft a logical conclusion that follows from and supports the thesis. 14. Revise for clarity and meaning. 15. Edit for capitalization, usage, punctuation, and spelling. 16. Compare this literary essay to literary paragraphs written during Unit 1. Post both versions on bulletin boards throughout the school. Archive originals in student portfolios. Language Standards (to be infused into unit as aims) L.8.2b Use an ellipsis to indicate an omission. L.7.1c Place phrases and clauses within a sentence, recognizing and correcting misplaced and dangling modifiers. L.3.1f Use subject verb and pronoun antecedent agreement. L.8.2c Spell correctly grade appropriate words. 10 Literature Aims Calendar Note: Lesson types are listed next to each day. Primary Aims are listed first. Secondary skills are listed beneath the primary aims in parentheses. Finally, suggested procedures and text selections are listed. Week 1 Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Distinguish between Make predictions Annotate text to Distinguish between Identify rhetoric as fact and opinion to and formulate emphasize key ideas relevant and the techniques an determine an author’s questions about the and supporting irrelevant author uses to position. author’s purpose by details. information in engage and Secondary Skills: previewing the text. Model Text: Chew on This, informational text. persuade the (The techniques a Secondary Skills: Secondary Skill: Introduction reader. nonfiction author uses (Review how to use an Secondary Skills: Independent Text: Bundle: to persuade his or her (Nonfiction narratives index to locate (Determine an author’s “Fast Food and Obesity in readers are used in and narrative elements information in an underlying opinion in Children and Adolescents” such as description are advertising, too.) informational text.) (Make predictions about a nonfiction book’s purpose, tone, and audience based on cover, layout, blurbs, visuals, author biographies, Table of Contents, chapters, and Index.) Model Text: Chew on This, whole book often used to engage, instruct, and persuade.) Model Text: Chew on This, “The Pioneers” (Determine the meaning of words with contentspecific definitions through context and/or use of a glossary.* (marketing/branding terms) Procedures: Have students create a 3-column chart of the parallels between advertising/persuasive nonfiction techniques (appeals to reason, emotion, ethics; informational text and the ways in which (s)he attempts to shape readers’ thinking.) (Distinguish between fact and opinion in informational texts.) Model Text: “McJobs,” Chew on This 11 education vs. brainwashing) Week 2 Day 6 Analyze how two or more authors writing about the same topic use different evidence to inform about that topic. Model Text: “The Secret of the Fries,” Chew on This Day 7 Evaluate informational nonfiction writers’ use of visuals, facts, statistics, and anecdotes as evidence for their arguments. Secondary Skill: (Identify anecdotes as a narrative pattern of writing.) Model Text: Stop the Pop, Chew on This Independent Text: Bundle article: “Activists Push for Day 8 Compare and contrast the organization of information about a similar topic from a variety of sources. Secondary Skills: (Recognize that a biography is the story of an individual’s life, written by someone else, and thus a type of narration.) (Analyze how a nonfiction author uses a biography to convey his or her opinion about Model Text: “The Youngster Business,” Chew on This Independent Text: Bundle article: “Scientist Reacts to San Francisco’s Happy Meal Ban.” Day 9 Identify and analyze how an author uses narration, description, and exemplification patterns to develop a central argument. Model Text: Big, Chew on This Day 10 Identify and evaluate conflicting information in two nonfiction texts through comparison. Model Text: Your Way, Chew on This Independent Text: bundle: “MELS, an NYC School Where Food Policy Is Part of the Curriculum” 12 Healthier School Lunches” Week 3 Day 11 Analyze key ideas across multiple texts and formulate judgments about which text(s) presents the most useful information.Model Text: Afterword, Chew on This Independent Text: NRA’s packet for schools reading Chew on This Day 12 Use rhetorical techniques to persuade readers of a viewpoint. society.) Day 13 Model Text: Meat, Chew on This Day 14 Day 15 Model Text: Whole book, Chew on This Independent Texts: Student-selected research articles 13 Writing Aims Calendar DAY 1 Develop an idea, topic, or basic claim about a recent literary text. DAY 6 Narrow the scope of the essay by eliminating subarguments and evidence that are not driven by the thesis. L.7.1c Place phrases and clauses within a sentence, recognizing and correcting misplaced and dangling modifiers. DAY 2 Locate specific and relevant evidence that supports their idea and will help develop their thesis. DAY 3 Revise their earlier idea by writing a clear and focused thesis statement that is not only defensible and accurately stated but is complex enough to support sub-arguments. DAY 4 -Select the best evidence that supports their thesis. -Plan the body paragraphs by listing sub-arguments and evidence. DAY 5 DAY 7 Draft the essay and incorporate analysis and interpretation of the meaning of text evidence. DAY 8 Draft the essay and incorporate analysis and interpretation of the meaning of text evidence. DAY 9 -Revise in order to ensure that indirectly cited evidence is paraphrased. -Revise in order to ensure that direct quotes are incorporated into other ideas and sentences. DAY 10 -Revise in order to ensure that every idea presented can be linked back to the thesis statement. -Revise in order to ensure that transition words, phases, and clauses that create cohesion among claims, interpretations, and evidence chunks. L.8.2c Spell correctly grade appropriate words L.3.1f Ensure subject-verb and pronoun-antecedent agreement L.8.2b Use an ellipsis to indicate an omission 14 DAY 11 DAY 12 Craft a logical conclusion that follows from and supports the thesis. Flex Day DAY 13 Edit for capitalization, usage, punctuation, and spelling. *Develop a research proposal L.3.1f Ensure subject-verb and pronoun-antecedent agreement DAY 14 Flex Day DAY 15 Compare this literary essay to literary paragraphs written during Unit 1. Post both versions on bulletin boards throughout the school. Archive originals in student portfolios. 15 L.8.2b Use an ellipsis to indicate an omission Simple Complex Aims to Support Development of the Standard Identify when an author uses an ellipsis to indicate an omission. Analyze the times an author chooses to use an ellipsis to indicate an omission. Strategically incorporate ellipses into their own writing to indicate omissions. L.7.1c Place phrases and clauses within a sentence, recognizing and correcting misplaced and dangling modifiers. Simple Complex Aims to Support Development of the Standard Identify phrases and clauses within longer sentences. Identify misplaced modifiers, i.e. “After our conversation lessons, we could understand the Spanish spoken by our visitors from Madrid easily.” Identify dangling modifiers i.e. “Raised in Nova Scotia, it is natural to miss the smell of the sea.” Correct misplaced modifiers in order to eliminate confusion, i.e. “We could easily understand the Spanish spoken by our visitors from Madrid.” Correct dangling modifiers by adding the missing subject, i.e. “Since I was raised in Nova Scotia, it is natural to miss the smell of the sea.” Evaluate own writing for dangling and misplaced modifiers, Correct own writing for dangling and misplaced modifiers. http://www.writingcentre.uottawa .ca/hypergrammar/msplmod.html L.3.1f Ensure subject-verb and pronoun-antecedent agreement http://www.proprofs.com/mwiki/i ndex.php?title=SAT_Writing_Cram Simple Complex Aims to Support Development of the Standard Identify the subject and the verb in a sentence. Ensure subject-verb agreement when using either…or / neither... nor in writing. Check writing for subject-verb agreement. Analyze published texts to see how authors ensure that subjects and verbs agree. Find examples of subjects and verbs that agree in their own writing. Construct sentences where the subject and verb agree. Revise writing to ensure that subjects and verbs agree. Identify the pronoun (substitute for noun) and its antecedent (original noun) Look for pronouns and figure out what to connect them to. Ensure personal pronoun-antecedent agreement in writing. Ensure possessive pronoun-antecedent agreement in writing. Ensure pronoun-antecedent agreement in comparisons (i.e. “I am happier than her) by inserting is at the end of the comparison (i.e. “I am happier than her is.” Or, “I am happier than she is.” Ensure indefinite pronoun-antecedent agreement (i.e. everyone, someone, somebody…) in writing. Ensure pronoun-antecedent agreement in: plurality, case, and gender in writing. Check writing for pronoun-antecedent agreement. 16 Find examples where pronouns and antecedents agree. A Scenario to Support Application of these Aims: After analyzing student writing, you realize that your students really struggle with subject/verb agreement. Although they can identify them on handouts and conjugate them in isolation, they are often unable to match the correct verb person to its corresponding noun while they are writing. Additionally, when revising or editing they tend to overlook correcting these mistakes. Thus, you review the list of aims above and decide to spend time in your next unit focusing on teaching students to: Identify the subject and the verb in a sentence. Analyze published texts to see how authors ensure that subjects and verbs agree. Construct sentences where the subject and verb agree. Revise writing to ensure that subjects and verbs agree. L.8.2c Spell correctly grade appropriate words Simple Complex Aims to Support Development of the Standard Create a “No excuses” spelling list that each 8th grade class commits to spelling correctly. Build a “No excuses” spelling list each IA cycle. Add words from literature, writing, and discussion. 17 8th Grade Unit 9 Assessment: Retooling School Lunch: It's lunch hour on a luminous spring day at Berkeley High School's open campus--the perfect time to stroll to Extreme Pizza on nearby Shattuck Avenue, grab a Coke, order some pizza heaped with sausage and sit in the California sun. But in Berkeley High's lunchroom, lines of students are waiting patiently for--get this-cafeteria food. The longest line--now get this--is for salad. "This is only my second time eating school lunch," says junior Fennis Brown, 17. "I've always been put off by cafeteria food. But when I saw a friend eating it, I thought, That looks like it could come from any good restaurant. And it's cheaper and easier than eating off campus." Such words herald a small battle won in the big food fight erupting over U.S. lunchrooms. With childhood-obesity rates zooming--more than a three-fold increase in 30 years--schools are under pressure from parents, health officials and legislators to serve something more wholesome than greasy burgers and Tater Tots. Across the U.S., administrators are banning deep-fat fryers from cafeteria kitchens. Sodamakers agreed last month to stop selling their sugary, fizzy products in schools. But bans are easy compared with changing how kids eat. How do you eliminate junk yet create meals that stay within tight budgets and satisfy fickle tastes? To find out, TIME went behind the lunchroom counter in two communities: Berkeley, Calif., where a well-funded program is converting students like Brown; and Shawnee, Okla., where financial and cultural pressures mean that change will come more slowly. The Cafeteria Crusader When Ann Cooper, Berkeley schools' director of nutrition services, sees the long lines in Berkeley High's cafeteria, she races behind a counter, grabs a pair of tongs and starts mixing made-to-order, all-organic salads. Only after the rush does she let herself gloat. "Yes!" she shouts, pounding her palm with her fist. "We had to have four people making salads, and there was no one waiting for pizza! This happened organically. I couldn't take their pizza away from them, but now they're doing it themselves." It didn't really happen organically. Over the past decade, Berkeley has become a paragon of school-lunch reform, thanks to the woman who helped hire Cooper-California cuisine pioneer Alice Waters. "We have to go into the public-school system and educate children when they're very young," says Waters, whose famed Berkeley restaurant, Chez Panisse, features seasonal meals made from local produce. Waters started educating children 10 years ago, creating the Edible Schoolyard at Berkeley's Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School. There, kids spend 90 minutes a week planting and harvesting produce and cooking their own healthy food. Even with such initiatives in place, school food was far from the Chez Panisse ideal before Cooper came to town last October. The bread was white, the fruit canned, the meat highly processed. Now Cooper has inked deals with local suppliers for whole-wheat rolls, fresh produce, even grass-fed beef. Her staff of 53, accustomed to reheating food from outside vendors for the 4,000 lunches, 1,500 breakfasts and 1,500 snacks served each day, is learning to make meals from scratch. It's lunch hour on a luminous spring day at Berkeley High School's open campus--the perfect time to stroll to Extreme Pizza on nearby Shattuck Avenue, grab a Coke, order some pizza heaped with sausage and sit in the California sun. But in Berkeley High's lunchroom, lines of students are waiting patiently for--get this-cafeteria food. The longest line--now get this--is for salad. "This is only my second time eating school lunch," says junior Fennis Brown, 17. "I've always been put off by cafeteria food. But when I saw a friend eating it, I thought, That looks like it could come from any good restaurant. And it's cheaper and easier than eating off campus." Such words herald a small battle won in the big food fight erupting over U.S. lunchrooms. With childhood-obesity rates zooming--more than a three-fold increase in 30 years--schools are under pressure from parents, health officials and legislators to serve something more wholesome than greasy burgers and Tater Tots. Across the U.S., administrators are banning deep-fat fryers from cafeteria kitchens. Sodamakers agreed last month to stop selling their sugary, fizzy products in schools. 18 But bans are easy compared with changing how kids eat. How do you eliminate junk yet create meals that stay within tight budgets and satisfy fickle tastes? To find out, TIME went behind the lunchroom counter in two communities: Berkeley, Calif., where a well-funded program is converting students like Brown; and Shawnee, Okla., where financial and cultural pressures mean that change will come more slowly. The Cafeteria Crusader When Ann Cooper, Berkeley schools' director of nutrition services, sees the long lines in Berkeley High's cafeteria, she races behind a counter, grabs a pair of tongs and starts mixing made-to-order, all-organic salads. Only after the rush does she let herself gloat. "Yes!" she shouts, pounding her palm with her fist. "We had to have four people making salads, and there was no one waiting for pizza! This happened organically. I couldn't take their pizza away from them, but now they're doing it themselves." It didn't really happen organically. Over the past decade, Berkeley has become a paragon of school-lunch reform, thanks to the woman who helped hire Cooper-California cuisine pioneer Alice Waters. "We have to go into the public-school system and educate children when they're very young," says Waters, whose famed Berkeley restaurant, Chez Panisse, features seasonal meals made from local produce. Waters started educating children 10 years ago, creating the Edible Schoolyard at Berkeley's Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School. There, kids spend 90 minutes a week planting and harvesting produce and cooking their own healthy food. Even with such initiatives in place, school food was far from the Chez Panisse ideal before Cooper came to town last October. The bread was white, the fruit canned, the meat highly processed. Now Cooper has inked deals with local suppliers for whole-wheat rolls, fresh produce, even grass-fed beef. Her staff of 53, accustomed to reheating food from outside vendors for the 4,000 lunches, 1,500 breakfasts and 1,500 snacks served each day, is learning to make meals from scratch. (8-10 MC questions, 2-4 open-ended, align to standards) 1. Which quotation best summarizes “Retooling School Lunch”? (RI.8.2) a. “With childhood-obesity rates zooming—more than a three-fold increase in 30 years—schools are under pressure from parents, health officials and legislators to serve something more wholesome than greasy burgers and Tater Tots.” b. “Over the past decade, Berkeley has become a paragon of school-lunch reform, thanks to the woman who helped hire Cooper— California cuisine pioneer Alice Waters. c. “How do you eliminate junk yet create meals that stay within tight budgets and satisfy fickle tastes?” d. “Fast-food-style marketing tricks, such as silver burger wrappers and plastic salad shakers, cost a little extra, but they boost sales.” 2. Which of the following is NOT a reason why the lunch reform program at Berkeley High School has been more successful than the programs in Shawnee? (RI.8.2) 19 a. Berkeley High School’s program is generously funded by the Chez Panisse Foundation, while Shawnee’s program relies on meager government funding and wealthier kids who choose to buy school lunch and snacks. b. The parents of Berkeley High School students are overwhelmingly supportive of the program, while Shawnee parents are critical. c. Berkeley students were educated about healthy eating from a young age. d. Deborah Taylor has to turn a profit, whereas Ann Cooper’s district allows her to rack up a $250,000 a year loss. 3. How does the author of “Retooling School Lunch” reveal his or her doubts that Berkeley’s program is exportable? (RI.8.6) a. (S)he says that Cooper concedes that the support she has is extraordinary. b. (S)he notes that while raw ingredients can be cheaper than processed food, cafeteria cooks must be taught how to buy, store, and prepare them. c. She presents the counter-example of Shawnee’s schools. d. All of the above 4. All of the following are supporting details of the section titled “The Meal Marketer”, EXCEPT: (RI.8.8) a. Taylor makes food healthier “by stealth”. b. Fast food style marketing tricks, such as silver burger wrappers and plastic salad shakers, cost a little extra, but they boost sales. c. Taylor has inked deals with local suppliers for whole-wheat rolls, fresh produce, even grass-fed beef. d. Shawnee school cafeterias resemble food courts at a mall. 5. What might a reader infer about the author’s purpose in “Retooling School Lunch” based on the section headings “The Cafeteria Crusader” and “The Meal Marketer”? (RI.8.2, RI.8.6) a. The author’s profile of Ann Cooper functions partly as a model of idealism. b. The author’s profile of Deborah Taylor functions partly as a model of capitalism. c. In contrasting these two extremes, the author suggests a middle-ground between them. d. all of the above 6. Which of the following MELS healthy eating initiatives could most easily be adopted in Shawnee schools? (RI.8.9) a. fieldwork b. food-awareness curricula across all subjects 20 c. a screening of Fresh for students and families d. all of the above. 7. Which of the following biases does the author of the article about MELS disclose? a. Her younger brother just started at MELS and is thriving. b. She feels obligated to temper a positive outlook on successful initiatives with a paragraph on the limitations of policy. c. She is friends with Damon McCord. d. She works for GrowNYC. 8. Which of the following is NOT discussed in the article about MELS? (RI.8.8, RI.8.9) a. the future of food programming at MELS b. school lunch at MELS c. funding for food-awareness curricula d. educating parents and family about healthy eating 9. Which rhetorical techniques are used in “Retooling School Lunch” that are not used in the article about MELS? a. The author of “Retooling School Lunch” uses the techniques of fiction to draw vivid scenes of the cafeterias at Berkeley High School and Shawnee schools. b. The author of “Retooling School Lunch” provides context for Ann Cooper’s and Deborah Taylor’s statements. c. The author of “Retooling School Lunch” contradicts statements made by Ann Cooper and Deborah Taylor. d. all of the above 10. Which of the follow-up questions below might Leah Douglas have asked Principal Damon McCord? a. What battles are you waging against the Department of Education, and how are you going about them? b. Do you think using fast-food marketing tricks to get kids to eat healthier school lunches furthers unhealthy eating habits outside of school? c. Is it fair to expect other school nutrition directors to invest so much into their lunch programs when they’re making a quarter of what you make? d. Does relying on junk food sales to make school lunch healthier negate the good you’re doing? 21 Open-Ended 9. Shawnee schools are offering students healthier lunches without food-awareness education, while MELS is offering food-awareness education without healthier lunches. If funding and policy limitations make only one of these initiatives possible, which would you choose and why? Support your answer with evidence from both “Retooling School Lunch” and the article about MELS. (RI.8.9) 10. Compare Ann Cooper’s, Deborah Taylor’s, and Damon McCord’s attitudes toward healthy eating reform in schools. Whose views seem most realistic? (RI.8.8) 11. Should fast food chain marketing techniques be used to get kids to eat healthy? Why or why not? Support your answer with evidence from both articles and Chew on This. (RI.8.9) 12. Annotate for the following rhetorical techniques in “Retooling School Lunch” and discuss how the author uses them to engage or persuade the reader of his or her position: techniques of fiction such as scene, dialogue, and imagery facts, statistics, and anecdotes larger context about the battle waging across the US over school lunchrooms, federal funding, etc. structure and organization of information Use the following rubric to assign points for this question: 4 3 2 1 Student effectively identifies all 4 rhetorical techniques and analyzes how the author uses each of these techniques to achieve his or her purpose. Student correctly identifies at least 3 of the 4 rhetorical techniques and demonstrates an understanding of how they relate to the author’s purpose. Student demonstrates a partial understanding of the above techniques and how they relate to the author’s purpose. Minimal response Inaccurate or off-topic response Grammatical mistakes impede meaning. 22 On-Demand Writing Assessment Bring in a novel that you have recently finished reading (as a class or independently). Make a claim about the protagonist. Be sure to include: a clear and focused thesis statement that is not only defensible and accurately stated but is complex enough to support subarguments and also drive every idea in the paper, body paragraphs that incorporate topic sentences that are assertions and present sub-arguments that are directly relevant to the thesis, paraphrased and direct text evidence that is directly relevant to the sub-argument, an analysis and interpretation of the meaning of text evidence, transitions words, phrases, and clauses that create cohesion among claims, interpretations, and evidence chunks, and a logical conclusion that follows from and supports the thesis. 23 Grammar 1. Read the paragraph below and fill in the blanks with the form of the verb in parentheses that agrees with its subject. (9 pts.) Fast-food restaurants________________ [to have] become more popular in America in recent years. Groups of people________________ [to drive] to burger and chicken places each day by the millions. Often, on one strip of road, there will be five or six places that_________________[to serve] hungry customers. Each and every restaurant_________________[to be] a member of a larger chain. Prices________________[to be] also controlled by the parent company. Of all the foods on the menus, hamburgers consistently_________________ [to perform] better than any other item. This is because American customers__________________ [to consume] hamburgers more than almost any other food. The nutritional value of these foods______________[to be] not the highest possible, but the food tastes so good that most people_________________[to be] happy to eat fast-food often. Besides, nobody_____________________[to prefer] nutrition over convenience all the time. 2. What is confusing about the following sentence? While jogging down the street, a dog bit my neighbor. Explanation: ________________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ Rewrite the sentence so that it makes sense: _______________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ 3. What is confusing about the following sentence? The car was parked on the edge of a cliff which was rusty. Explanation: ________________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ Rewrite the sentence so that it makes sense: _______________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ 4. What is the purpose of an ellipsis? 24