File

advertisement

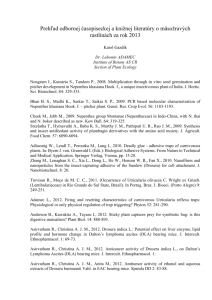

The Nepenthes Genus Christopher Birck William R. Tanner BIOL 1035 November 25, 2014 Nepenthes: The Tropical Pitcher Plant Genus The species of plants that fall under the Nepenthes genus, more commonly known as “Tropical Pitcher Plants,” are a fascinating feature of nature and evolution. They are known for their pitcher-like appendage that is used to attract, trap, and ingest the nutrients of small prey; making them carnivorous in nature. Another common name for these plants is “monkey cups,” which refers to the fact that many have observed monkeys drinking the mixture of rainwater and sweet nectar from them. Nepenthes is the only genus in the Nepenthaceae family of botanical taxonomy, yet there exists a degree of diversity among the plants within this genus (Basumentary). The diversity that can be noted consists of differences in color, shape, size and other distinguishing factors that depend on the plant’s environment (Moran). They are a flowering genus of plants that depend on pollinators and in some cases, symbiotic relationships with other organisms for survival (Moran). They are naturally found in regions of Southeast Asia, but many cultivate them in greenhouses and homes all over the world (Moran). Every species in the Nepenthes genus are clearly distinguished by their pitcher-shaped traps that ingest the nutrients of other organisms from termites to small rats (Cresswell). The range of prey that the Nepenthes plants are additionally known to have trapped include spiders, insects, frogs, snails, slugs, lizards, and even small birds (Cresswell). Much more rare in occurrence, the ingestion of larger prey such as small rats or birds have actually proven to be harmful to the lifespan of the plant’s trap (Cresswell). Nepenthes traps are filled with a viscoelastic fluid that is effective in the attraction and trapping of winged insects, among other organisms (Moran). The peristome, or the rim of the pitcher, contains glands that releases a sweet nectar like substance; and is also very slippery in nature (Wang). This provides a very effective system in trapping prey: the prey is attracted to the trap by the sweet smells of nectar, climbs over the peristome and aquaplanes, or slips, into the trap’s fluid causing the prey to drown (Moran). The fluid contains digestive enzymes that allow for the glands in the bottom part of the trap to absorb the nutrients of the prey (Moran). The trap also has a lid that covers the opening of the trap, preventing rain from diluting the viscoelastic fluid (Cresswell). The underside of the lid also contains nectar glands for prey attraction. The upper portion of the inside of the trap is coated in a slick wax-type substance that makes escape almost impossible. (Wang). The flowers that grow from these plants are generally small and colorful, containing four sepals that are covered in nectar glands; along with a prominent pistil and an inferior ovary (Basumentary). Seeds are produced in a four-sided capsule that can contain anywhere between 50-500 seeds, each made up of a central embryo and two outwardly protruding wings on either side (Basumentary). The flanking wings suggest that the seeds are dispersed by wind. Pollination occurs with the aid of pollinating agents such as flies or wasps, transferring pollen grains from male plants to the receptors of the female plants (Basumentary). The Nepenthes flowers’ bright colors as well as the nectar produced by the sepals attract these agents to promote this transfer in order for breeding (Basumentary). Pitcher plants consist of a shallow root system and a prostate, or a climbingstem, from which blade-like leaves grow (Moran). From the stem grows the plant’s tendril, which in most species aids the plant in climbing up trees (Moran). The pitcher-like trap grows from the end of the tendril, starting from a small bud that eventually grows into a larger spherical, or tube-like trap (Moran). The tendrils of most species often form a loop just before the trap that is used for support by wrapping itself around surrounding supporting structures (Moran). Although all somewhat similar in anatomy, shape, and function; there exists significant diversity among the pitcher plants. The most clear indicator of diversity among Nepenthes species is whether the plant grows and forms its trap on groundlevel, or if it is aerial, and has established itself anywhere from 5-20 feet above ground attached to a tree (Baur). As juveniles, these plants are usually grounded with the opening of the pitcher facing its tendril (Baur). As they mature, most species become epiphytic and climb there way up trees with the pitcher opening facing outward; however, there are species that remain at ground level (Baur). Some species distinguish themselves by specializing in specific prey. N. albomarginata, for example, mostly feeds on termites and contains no nectar glands; and N. mirabilis preys mostly on ants (Moran). Not all species of Nepenthes, however, feed only on animals. N. lowii, for example contains nectar glands on the underside of its lid and provides a perch on its peristome for birds or tree shrews to stand to feed on the nectar while the trap catches the agent’s falling excrement (Moran). N. ampullaria is known for catching and ingesting dead plant parts such as leaves, bark, or small branches that fall from the canopy of its surrounding rainforest (Moran). Pitcher plants grow in habitats of extremely poor nutrients (Baur). The soil from which these plants grow is usually on the acidic side and contains little nutrients that are essential for survival, causing the necessity to obtain such nutrients by ingesting other organisms (Moran). Other factors in which pitcher plants thrive in include high humidity, and moderate to high light levels (Moran). Such environments include mountain rainforests, swamps, sandy environments, and sometimes savanna-like grass communities (Moran). These environments are common in the regions of China, Sumantra, Madagascar, Philippines, Sri Lanka, India, North-West Australia, New Caledonia, Seychelles, and the Boneo rainforests (Moran). Most species are restricted to very small ranges, with some species that can only be found on specific mountains or islands (Moran). Pitcher plants form many ecological relationships with other organisms that share the environment (Basumentary). The most obvious is that of predator and prey: these plants rely on insects, spiders, frogs, snails and other organisms to fall into their traps to ingest those vital nutrients their prey provides. Additionally, some species form symbiotic relationships with other organisms that provide benefits for the survival of both the plant and the other organism (Cresswell). Many species often provide protection, shelter, and food for organisms such as mosquito, fly, and midge larvae that in return provide expedited digestion for the plant (Cresswell). These organisms that spend at least part of their lives within the pitcher of these plants are often called Nepenthes infauna (Cresswell). Other species, N. bicalcarata, for example, provide space in their hollow tendrils for carpenter ants to build nests (Cresswell). These ants take away bigger prey from the plant, reducing the amount of substances that could be harmful to the plant or the infaunal organisms while providing nutrition for the ants themselves (Cresswell). Another symbiotic relationship can be seen between N. lowii and tree shrews, with the plant providing nectar for the shrew while the shrew defecates into the plant’s trap, providing nutrients for the plant (Moran). There are over 150 known species that belong to the Nepenthes genus, with that number getting larger every year (Baur). These unique plants have provided fascination and interest among botanists ever since the days of Carolus Linnaeus in the early 18th century (Robinson). The term “Nepenthe” translates to “without grief,” referring to a passage in Homer’s The Odyssey that describes a drug that soothes all feelings of sorry with forgetfulness (Robinson). The pitcher plant enthralled Linnaeus to the point of naming these plants after this mythical drug (Robinson). He explains that the mere sight of such an exotic and wonderful plant will diminish the pains of any botanist and extinguish the memory of any past ills or grieves (Robinson). Not only are these plants unique because of their pitcher-like traps and their carnivorous nature, but also because of the bright and vivid colors that they are decorated with. Pitcher plants are very conspicuous in their environments and clearly stand out among other vegetation that surrounds. This, among many others, is a reason why many around the world choose to cultivate these exotic plants in personal greenhouses. Works Cited Basumatary, Sadhan K., et al. "Pollen Morphology Of Nepenthes Khasiana Hook. F. (Nepenthaceae), An Endemic Insectivorous Plant From India." Palynology 38.2 (2014): 324-333. Academic Search Premier. Web. Baur, U., et al. "Form Follows Function: Morphological Diversification And Alternative Trapping Strategies In Carnivorous Nepenthes Pitcher Plants." Journal Of Evolutionary Biology 25.1 (2012): 90-102. Academic Search Premier. Web. Cresswell, James E. "Resource Input And The Community Structure Of Larval Infaunas Of An Eastern Tropical Pitcher Plant Nepenthes Bicalcarata." Ecological Entomology 25.3 (2000): 362-366. Academic Search Premier. Web. Moran, J.A., W.E. Booth, and J.K. Charles. "Aspects Of Pitcher Morphology And Spectral Characteristics Of Six Bornean Nepenthes Pitcher Plant Species: Implications For Prey Capture." Annals Of Botany (United Kingdom) (1999): AGRIS. Web. Robinson, Alastair S., et al. "A Spectacular New Species Of Nepenthes L. (Nepenthaceae) Pitcher Plant From Central Palawan, Philippines." Botanical Journal Of The Linnean Society 159.2 (2009): 195-202. Academic Search Premier. Web. 23 Nov. 2014. Wang, Lixin, and Qiang Zhou. "Nepenthes Pitchers: Surface Structure, Physical Controlling Plague Locust." Chinese Science Bulletin 59.21 (2014): 2513-2523. Academic Search Premier. Web.