6 Final Paper

Name Redacted

H206

June 17, 2010

Educating Social Mobility

During the second half of the eleventh century education began to expand beyond the lines of the aristocratic elite and the monasteries.

Although the efforts of Justinian, Charlemagne, and King Alfred remain as noble and effective attempts to improve the intellectual activity of the masses, education remained the product of political gain and reform. With the introduction to Gregorian reform and the Third Lateran Council in 1179, education began to spread into a more personal endeavor. As a result,

Abelard, Heliouse, and the Rozmberk sisters were able to improve their standing among themselves and others through their education.

One of the most prominent figures in the push of education for political reasoning was Justinian. He ruled the Byzantine Empire from 527-565 and is noted for the taking on the project of organizing and reissuing the whole written corpus of Roman law. He pushed for more education among those who were working with him on the Roman law projects because a better understanding of written texts was required for the project to be completed.

While this project was immense in and of itself it resulted in a process of better teaching and understanding of the legal codes (Medieval Worlds, 96).

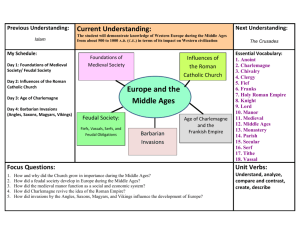

Charlemagne offered a major push for education during his rule in the

Carolingian Empire from 768-814. Although intellectual activity started during Pippen II, Charles Martel, and King Pippin’s rule, it did not take hold until Charlemagne took control. This push for better clerical education happened because he was “deeply concerned about the spiritual well being of his subjects,” (Medieval Worlds, 149). This movement became known as the Carolingian Renaissance (Medieval Worlds, 149). Charlemagne took an active role during this movement by advocating for the better education of the clergy members. He accomplished many things during this movement where he “issued decrees, set standards, and supported a system of schools for the education of the ordinary clergy and often lay people as well,”

(Medieval Worlds, 149). It was extremely important during this time that the clergy is well educated for political reasons because the church and state were so closely tied together. An uneducated clergy could result in a weak government. Charlemagne had such an impact on the realm of education that even after his rule was over the rise continued under his son Louis the

Pious.

Yet another effective proponent of education of clergy members for political power was King Alfred. He realized that the education of his priests was suffering so badly that they struggled to perform liturgical duties within the church. During his reign his concern was the education of his clergy members and as a result he began to restock the monasteries with books

since the majority had been burned during the Viking invasions (Medieval

Worlds, 183). Since he was educated himself, he immediately gained more power in his efforts to reform the education of his clergy members. He provided translations of several books from Latin to Old English and provided

England with an intellectual and ecclesiastical footing for the future.

All three of these men put in great efforts to reform the education of the clergy to ensure a stronger political structure and to create mass communication between the classes more effective. Even though they made great strides in education during their time, education still existed mainly in realm of the aristocratic elite and the monasteries particularly for political involvement and power. Up until the beginning of the eleventh century an education served mainly one function which was to create a stronger political unit by ensuring that the clergy was well educated not only in literacy terms but also in legal aspects since the church and state seemed to serve as one unit. When the Gregorian reform and the Third Lateran Council began education was becoming more mainstream and shifted from being political in nature to a more personal pursuit.

Peter Abelard is one example of this personal pursuit for education.

Since he is the first born in his family his education was given more attention than his brothers. He is the son of a knight who has minor training in ‘letters’ and his father has a great appreciation for this knowledge and as a result expects his sons to be trained in ‘letters’ as well. This excerpt taken

from the Historia Calamitatum demonstrates Abelard’s choice in receiving an education for personal reasons rather that political…

My father had acquired some knowledge of letters before he was a knight, and later on his passion for learning was such that he intended all his sons to have instruction in letters before they were trained to arms. His purpose was fulfilled. I was the firstborn, and being specially dear to him had the greatest care taken over my education. For my part, the more rapid and easy my progress in my studies, the more eagerly I applied myself, until I was so carried away by my love of learning that I renounced the glory of a military life, made over my inheritance and rights of the eldest son to my brothers, and withdrew from the court of Mars in order to be educated in the lap of Minerva.

As a result of the decision to pursue education for personal gain,

Abelard was able to become the master of his own school sometime between 1110-1112 at the abbey of Mont-Sainte-Genevieve.

Similarly, Heliouse and the Rozmberk sisters make education a personal pursuit because of the shift in educational availability, despite the fact that they are women during a period where women were granted little power and authority. Heliouse is very well educated for a woman during this time and is also thought to have spoken three languages; Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. “One three occasions Abelard credits her also with knowledge of Greek and Hebrew, noting that she is ‘alone at this time adept in the experience of the three tongues’,”

(Medieval Worlds, 372). She is among the many educated women that have devoted their lives to the convent.

Just as Heliouse becomes educated as a personal endeavor, so do the Rozmberk sisters. Despite the fact that the sisters come from a politically powerful noble family their education is still seen as personal rather than political. Whereas Heliouse receives an intellectual education, the Rozmberk sisters receive an education that is more based in social success, “As potential marriage candidates, the daughters required abilities and knowledge which would determine their success,” (The Letters of the Rozmberk Sisters, 5). It is evident that while all three women received an education and were able to read and possibly write on their own, there was a difference in the type of education that the women received. Since Heliouse was part of a convent her education was rooted in literacy, rhetoric, and languages, while the sisters, whom neither were a member of a convent, received a more social form of education.

Additionally, it is clear that there is a difference in the educational success between the sisters. Perchta’s education is based in the matters of being a wife, “The most important part of Perchta’s education was that as a wife she had to obey and submit to her husband, her new lord,” (The Letters of the Rozmberk Sisters, 6).

While Perchta’s education was that of a wife, Anezka, who remained

unmarried, became educated in the agricultural sector partly because she was a land owner and in her last will and testament was successfully able to distribute her property and possessions among her survivors. Although during their time the sisters’ family was under great political unrest as a result of their fathers heavy monetary participation in the Hussite Revolution, their education did nothing to improve themselves, as women, in the political realm.

Even though most members of medieval society who did receive an education were among the nobility, their reasoning behind acquiring this education differs. Justinian, Charlemagne, and King

Alfred all push for education to further their political endeavors allowing for communication to be fostered with greater ease while leaving a legacy behind of their efforts and education. Abelard,

Heliouse, and the Rozmberk sisters seek education on a more personal level to ensure their own legacy. The shift in education from political reasons to personal reasons thus begin to pave the way for a more institutionalized form of education for the masses and also gives rise to the idea of the individual.

Bibliography

Abelard, Peter. Historia Calamitatum

Cruz, Jo Ann H. Moran, and Richard Gerberding. Medieval Worlds: An

Introduction to European History 300-1492. New York: Houghton

Mifflin Company, 2004. Print.

Rozmberk, Anezka and Perchta. The Letters of the Rozmberk Sisters