Jake Cogswell, Stephen Pistorius, Whitney

advertisement

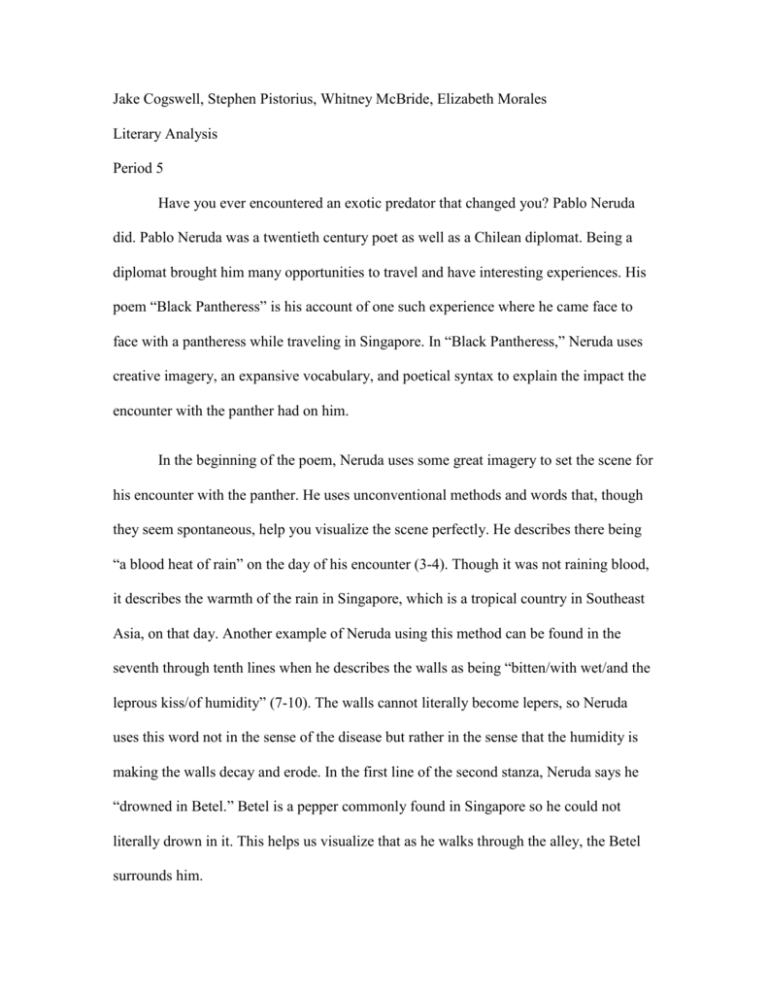

Jake Cogswell, Stephen Pistorius, Whitney McBride, Elizabeth Morales Literary Analysis Period 5 Have you ever encountered an exotic predator that changed you? Pablo Neruda did. Pablo Neruda was a twentieth century poet as well as a Chilean diplomat. Being a diplomat brought him many opportunities to travel and have interesting experiences. His poem “Black Pantheress” is his account of one such experience where he came face to face with a pantheress while traveling in Singapore. In “Black Pantheress,” Neruda uses creative imagery, an expansive vocabulary, and poetical syntax to explain the impact the encounter with the panther had on him. In the beginning of the poem, Neruda uses some great imagery to set the scene for his encounter with the panther. He uses unconventional methods and words that, though they seem spontaneous, help you visualize the scene perfectly. He describes there being “a blood heat of rain” on the day of his encounter (3-4). Though it was not raining blood, it describes the warmth of the rain in Singapore, which is a tropical country in Southeast Asia, on that day. Another example of Neruda using this method can be found in the seventh through tenth lines when he describes the walls as being “bitten/with wet/and the leprous kiss/of humidity” (7-10). The walls cannot literally become lepers, so Neruda uses this word not in the sense of the disease but rather in the sense that the humidity is making the walls decay and erode. In the first line of the second stanza, Neruda says he “drowned in Betel.” Betel is a pepper commonly found in Singapore so he could not literally drown in it. This helps us visualize that as he walks through the alley, the Betel surrounds him. Neruda’s use of descriptive vocabulary also contributes to the picture of the setting in the readers mind. In the fifth line, he calls the walls “moldering” which means “turning to dust” (5). This reinforces the picture of the aged and decaying walls surrounding him. Neruda also describes the sun to be “implacable,” which is a synonym of merciless (16). This word helps us visualize the heat of the sun beating down upon him through the clouds. The poetical architecture also helps him create imagery. He uses his lines and line breaks to put emphasis on particular words that help describe the setting. For example, in the seventh line, he separates the word bitten from the other lines even though there is room on the line to put it. He wants to emphasize the fact that the walls are slowly being eaten away. In the seventeenth line, he separates iron from the rest of the poem as well. He wants to emphasize the unchanging nature of the sun in the sky. Neruda introduces the theme element of the poem in the next lines. Up until this point, Neruda has described the city of Singapore as he traveled its alleys. None of what he has seen has given him pause, but what he sees next commands his attention. Neruda writes that he “suddenly saw it/the face in a cage/by my face” (26-28). His first sighting of the pantheress was both sudden and up close. He found himself unexpectedly staring this creature in the eye. Out of all the parts of a panther Neruda could have described, he chose the eyes first. He did this to show that what he saw in those eyes had the most impact on him. By using these lines as his introductory description of the pantheress, Neruda ensures that they will influence the reader’s opinion in much the same way that people are influenced by their first impression of a stranger. Neruda describes the panther’s eyes as “magnets” (32). He implies that the eyes draw his gaze to them. No matter how hard he struggles, the panther’s eyes draw his own to them. He also describes its eyes as “electric antagonists” (33). Neruda uses these words to evoke in his readers the hostility he felt emanating from the panther’s gaze. Neruda’s use of this phrase makes his readers view the panther as dangerous, maybe even as an enemy, from the moment he introduces it. The final description Neruda gives of the eyes makes them seem like living things. The way he writes makes it seem that the pantheress’ eyes are drilling through his and bolting him to the ground. His writing easily brings to mind the image of a man transfixed by the gaze of a predator. This image, as well as the idea that the panther is hostile, remains with the reader throughout the rest of the poem. Neruda next uses a line with the single word “saw” to show that he is changing topics (26). By having that word on its own line, Neruda takes the readers attention off of the panther’s eyes and prepares them for the next description of the panther. That description centers on a motion the pantheress makes, a simple “surge,” as Neruda writes. Yet that simple motion has great impact on him (40). He describes the panther’s “flexing perfection” in one line, and on the next again describes it as “darkness made perfect” (4344). Neruda twice describes the pantheress as perfect. In doing so, he conveys the great respect he had gained for this creature merely by looking at it. Throughout the third stanza, Neruda uses short lines, the longest being only five words. The short lines make the reading somewhat slower and choppier. However, it emphasizes the relationships between the words of each line. Every line relates either to describing the look of the panther, or an action it is performing. The separation of these descriptions into lines makes each part of the description stand out more, making it more memorable and impactful to the reader. One such example that really stood out was when he described the pantheress eyes as “electric antagonists” (27). This description was far more memorable by itself than it would have been if it was on a line with another description. Besides using varying lengths of lines, Neruda also uses expressive vocabulary to compare the pantheress’ skin to the night and soon after he talks about her transparency. This shows that the pantheress has skin similar to that of the night itself, and that she seems almost transparent as she blends in with the night. He continues to describe the pantheress as having a bit of sparkle in her eyes, “like a pollen-fall,” as well as comparing the flecks of brightness in her eyes to a gold hexagon or a topaz rhombus (47). Using these words shows that the only reason he could see the pantheress was because of her bright eyes. It creates a somewhat contrasting image because pollen looks pretty, but also causes allergies and annoyance. Just as the pantheress looks beautiful, she can cause harm as well. Neruda shifts the focus back to her general appearance when he explains that she had a “tapering/presence” that has “displaced itself” (53-55). The words “tapering” and “displacement” show that the pantheress has dwindling health and does not seem to be completely present. Neruda adds to her apparent lack of health by describing her as “throbbing.” The word throbbing represents the pain the pantheress feels. Neruda’s final description of the pantheress in this stanza shows it “thinking/its thoughts,” this builds in the readers a sense of curiosity as to what the pantheress ponders (57-58). Besides using an expansive vocabulary, Neruda makes use of certain line breaks to add to the image. He sets specific words on a line by themselves; causing us to pay special attention to those lines as well as making us read those parts a bit slower. Specifically, the word midway set off on a line by itself shows that it contains significance. It does not seem like one word would particularly matter to the poem. However, when looked at as part of the whole section, the word midway shows us that the pantheress was not completely on the trash but was instead only midway on the trash. This shows that the panther has not been entirely covered in filth, and can still maintain some dignity. In the last few lines of the third stanza, Neruda creates a very powerful image when he describes the pantheress as “a/barbarous/queen” (60-61). Comparing the pantheress to a queen shows the pantheress’ beauty and rank; however she resides in squalor. This makes the reader feel that the cage and filth are not worthy of such a queen. Using this image of a queen expresses the idea of a wrongly imprisoned pantheress, who belongs somewhere worthy of her caliber. This, in turn, creates the feeling that no animal deserves placement in some box in the street. Neruda clearly feels that the pantheress deserves to live in a jungle and not in such lowly conditions. Although the poet lived before animal rights activism gained major attention, the reader can clearly tell that Neruda feels that the pantheress was wrongly treated. In the last two stanza’s “The Black Pantheress,” Pablo Neruda uses very creative imagery to set the mood of how dangerous and powerful the city is, similar to the panther. He describes the city in such a way as to make it appear untrustworthy. The description of the scene also shows a very quiet and dangerous environment, almost as if the panther is influences everything in its surroundings. Neruda’s words make the whole alley seem cramped, similar to the pantheress’ cage. He next explains how bittersweet the life of the pantheress has become, having once been a queen, and yet now she has fallen from the top of the food chain. The next few lines compare the dwellings of the humans, calling them “powdery” (72). Neruda uses this word to emphasize the softness of the humans compared to the predatory strength embodied in the pantheress. As he continues to describe the panther, he once again describes her eyes. The pantheress’ eyes, described as “mineral,” declare her strength and her contempt for all she sees (75). Neruda also describes her eyes as “unbreakable/seals” focused on the jungle (80-81). He clearly felt that the pantheress still longed for her home. In the last stanza of the poem, Neruda explains that the panther “walked/like a holocaust” (85-86). With these words he paints a picture in the reader’s mind the destruction and death that the pantheress is capable of causing, reaffirming his opinion of her dangerousness. Neruda ends the poem when he loses sight of the pantheress. She closes her eyes, and her dark skin blends completely into the “smoke” of night (87). This part of Neruda’s poem gives the pantheress an air of mystery. The final line says that the pantheress “was one with the night,” which makes the reader feel that the pantheress finally gained some freedom (88). This conclusion shows the evolution of Neruda’s feelings towards the creature he stumbled upon, starting with surprise and fear, then progressing to respect, and even awe towards this majestic and mysterious creature. Through creative imagery, the structure of the poem, and descriptive vocabulary, Neruda depicts with vivid detail his encounter with a foreign predator. With these literary devices, the poem shows the awe he feels for this panther and the way it has affected him. Pablo Neruda’s “Black Patheress” a poetic masterpiece.