Nagarajan.EAP Conceptual paper

advertisement

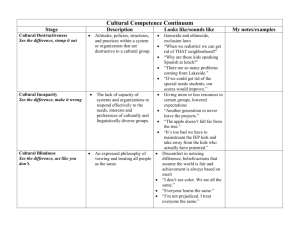

Running head: Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs The relevance of incorporating Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs A conceptual paper Sudha Nagarajan Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs 2 The relevance of incorporating Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs The world of work in the 21st century reflects vast structural changes and will continue to evolve in response to trends in the economy and society. Globalization and technology are two factors that have contributed to the mobility of people and businesses, enabling exchange of ideas and competitiveness in the marketplace. The contemporary world of work reflects changes in economies and industries, including rising investment in business services, outsourcing, technological impact, mobility, wars impacting the economy, immigrant workers, and the changing nature of employees because of globalization (“Futurework”, 2000). In their report, Egerter, Decker, An, Grossman-Kahn and Braveman (2008) described the changes in the world of work in the 21st century from manufacturing to service industries, multidisciplinary jobs requiring knowledge-based work, workforce diversity reflected in terms of age, gender and ethnicity, increased use of technology and collaborative work. The report also highlighted the detrimental impact of workplace culture, job demands, physical and psychological strain related to balancing work and family life, social support at work, and gender and racial discrimination in the workplace on employee productivity and health. The evolving nature of work and attributions of meaningful work depend on many subjective factors based upon material and psychological satisfaction (Steger, Dik & Duffy, 2012). Compensation for work could relate to decisions regarding healthcare and lifestyle. Traditionally, job benefits include health insurance, paid sick leave, access to workplace wellness programs, retirement planning, legal services, childcare services and behavioral healthcare. Some of these workplace benefits are offered through Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs). The traditional function of EAPs is to provide a wide-range of services for Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs 3 employees as well as provide consultation and strategic planning for organizations through knowledge and expertise of professionals trained in human behavior and mental health (EAPA, 2011). These functions are designed to enable a healthy work environment fostering growth for the organization and its employees. The development of EAPs is related to the need of employers to manage the adverse effects of alcoholism on workplace productivity, working in conjunction with worker’s compensation laws for employee safety (Sandys, 2012). The program was supported by the passage of The Hughes Act of 1970 and the Drug Free Workplace Act of 1988, mandating the development of education and support for employees struggling with alcoholism and substance abuse through workplace interventions (Kurzman, 2013). Eventually, as the need grew, the services of EAPs increased to include employees and their family members and offered a wide range of services including mental health, work-life balance, crisis intervention, childcare, elder care, wellness and prevention. This expansion of services (Steele, 1998) also corresponded with the development of standards and guidelines for EAP practice (EAPA, 2010) through accrediting bodies in order to define the role and functions of EAPs with local and global significance (EASNA, 2013). EAP programs and services are modeled on the principle of evaluating employee work performance, distinguishing it from the functions of occupational health services, coaching, and mental health services (EASNA, 2009). The core functions of EAPs have been defined by their accrediting bodies to include assistance to leadership, training for employees, confidential services to employees and their family members, timely problem identification, assessment, short-term interventions and treatment referrals, and performance evaluations (EAPA, 2010). Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs 4 Commissioned by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS), the National Business Group on Health (NBGH) formed the National Committee on Employer-Sponsored Behavioral Health Services (NCESBHS), which reported on “recommendations to improve the design, quality, structure and integration of employer-sponsored behavioral health services” (NBGH, 2008, p. 5). The report is very comprehensive, focused on the business value of EAPs for organizations, highlighting the returnon-investment (ROI) prospects of utilizing an effective EAP, and identifying the major challenges for designing programs in keeping with current trends in the workplace. The NBGH (2008) definition for highly effective EAPs reads: “Employee Assistance Programs provide strategic analysis, recommendations, and consultation throughout an organization to enhance its performance, culture, and business success. These enhancements are accomplished by professionally trained behavioral and/or psychological experts who apply the principles of human behavior with management, employees, and their families, as well as workplace situations to optimize the organization’s human capital.” The core functions of EAPs are summarized as: conducting assessment of needs, regulatory compliance, advisory functions, service delivery functions, policies and operating procedures, staffing criteria and regulations, case consultations, supervision, professional development, record keeping, ethical issues, including confidentiality and regulatory guidelines (EAPA, 2010). The Council on Accreditation (COA), which serves to accredit EAPs, defines the program in terms of certain core technology, as published by EAPA (2010, p.6): Consultation with, training of, and assistance to work organization leadership (managers, supervisors, and union officials) seeking to manage troubled employees, enhance the work environment, and improve employee job performance; Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs 5 Active promotion of the availability of EA services to employees, their family members, and the work organization. Confidential and timely problem identification/assessment services for employee clients with personal concerns that may affect job performance; Use of constructive confrontation, motivation, and short-term intervention with employee clients to address problems that affect job performance; Referral of employee clients for diagnosis, treatment, and assistance, as well as case monitoring and follow-up services; Assisting work organizations in establishing and maintaining effective relations with treatment and other service providers, and in managing provider contracts; Consultation to work organizations to encourage availability of and employee access to health benefits covering medical and behavioral problems including, but not limited to, alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental and emotional disorders; and Evaluation of the effects of EA services on work organizations and individual job performance. While these roles and responsibilities address the essential functions of EA services, they lack specific mention of adaptation of services to meet emerging workplace needs. Stakeholders in the EA industry and researchers in the field like Attridge (2012) endorse the adaptation of EAP Core Technology to suit the specific needs of organizations in different countries as a trend for EAPs. Given the huge diversity in the current workplace such as differences due to ethnicity, age, gender, sexual orientation, ability and returning military personnel to a civilian workplace, cultural competence can be viewed as a basic requirement for employees, management and organizations. Organizations have a corporate social responsibility to address the healthcare Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs 6 needs of vulnerable groups of employees, which is demonstrative of the ROI in terms of improved productivity. In the wake of changing trends in the workplace, EAPs have made reciprocal adjustments to their role and in their service delivery. These adjustments not only include change and expansion of services offered (Steele, 1998) but the development of standards and guidelines for practice in employee assistance programs (EAPA, 2010) as well as the establishment of an accrediting body (EASNA, 2013). The Employee Assistance Professionals Association (EAPA, 2010) and Employee Assistance Society of North America (EASNA, 2013) are committed to the development of standards of excellence for EAPs, providing ongoing educational needs of EA professionals, focusing on the development of EAP core technology and best practices, and identifying areas for research. EASNA, described as a trade association of the employee assistance industry, was designed in 1985 to conduct research, and provide education, and advocacy of mental health and wellness in the workplace in addition to the development of best practices for EAPs. The EAPA Standards and Professional Guidelines (2010) stated that program design must incorporate the needs and goals of the employees and the organization, and evolution and assessment of programs should be continuous in keeping with changing needs. The following standards are noteworthy in this context: E. ADDITIONAL SERVICES STANDARD: The employee assistance program shall remain alert for emerging needs and may add new services when they are consistent with and complementary to the employee assistance program (EAP) core technology. (EAPA, 2010, p. 10). Though EAPs offer services to employees and dependents to address their mental and emotional wellbeing, an argument can made that there is under-utilization of such services for a Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs 7 plethora of reasons. Some of the reasons for under-utilization of EA services include lack of visibility of services, stigma and discrimination regarding mental health and addictions, and external models with reduced promotion and usage (Attridge, 2012). The trends in EAP models reflect the inclusion of proactive and consultative services, and the role of mental health in employee productivity and organizational performance (Attridge & Burke, 2011). Making the workplace an avenue to reduce healthcare disparities can ensure both employee wellbeing and organizational productivity, maximized by the provision of services that are culturally appropriate. This orientation towards cultural sensitivity must be incorporated into the core philosophy of the EA industry as a timely recognition of the need to acknowledge the impact of diversity and inclusion in the workplace. Indeed, if new services addressing diversity needs are included to EAPs, it should be reflected in the EAP Core Technology as a standard that is “complementary and consistent” with it (EAPA, 2010, p. 10). Cultural competence is best understood from the context of healthcare equity and equal employment opportunity. According to the Office of Minority Health, a division of the United States Health and Human Services department, an adaptation of cultural competence as developed by Cross, Bazron, Dennis, & Isaacs (1989) reads as follows: Cultural and linguistic competence is a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals that enables effective work in crosscultural situations. 'Culture' refers to integrated patterns of human behavior that include the language, thoughts, communications, actions, customs, beliefs, values, and institutions of racial, ethnic, religious, or social groups. 'Competence' implies having the capacity to function effectively as an individual and an organization within the context of the cultural beliefs, behaviors, and needs presented by consumers and their communities. Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs 8 Cross et al. (1989) postulated the development of cultural competence along a continuum of cultural destructiveness, incapacity, blindness, pre-competence, basic competence to advanced competence. The National Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) Standards, based on this definition, are a mandated set of culturally competent services that are required of the health service industry (Office of Minority Health, USDHHS, n.d.). The taskforce of the Office of Minority Health (OMH), in conjunction with the agency of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), is dedicated to develop initiatives to reduce healthcare disparities among a growing population of minorities through collaboration with governmental agencies such as: National Institute of Health (NIH), Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), Food & Drug Administration (FDA), Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ). The specific goals of the DHHS Action Plan (DHHSOMH, 2015) to address healthcare disparities include “improving cultural competency and diversity of the behavioral health workforce” (p.18). Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development (GUCCHD) has conducted a lot of research on cultural competence based on the work of Cross et al. (1989). In order to practice cultural and linguistic competence, organizations are required to value diversity in the workforce, conduct self-assessment for cultural competence, effectively manage the dynamics of a diverse and globalized marketplace through the incorporation of values and policies that reflect inclusion, and implement diversity practices in policy making, administration, and service delivery. Such an institutionalized practice of cultural competence is required to involve consumers, key stakeholders and communities for organizations to adapt to a constantly evolving globalized workplace (National Center for Cultural Competence, GUCCHD, 2004). Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs 9 According to an Executive Order 13583 (2011), issued by President Obama, ‘workforce diversity’ refers to differences between people that can be based on characteristics such as race, ethnicity, language ability, age, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, family structure, and disability. ‘Inclusion’, is the organizational culture facilitating connection of employees to the organization through collaboration, anti-discriminatory practices, and empowerment through equal opportunity. The Executive Order (2011) highlighted three goals specific to the federal workplace: diversity, inclusion and sustainability achieved through the adoption of identified best practices to promote integration, collaboration and equal opportunity. In citing federal laws pertaining to such practice in governmental workplaces, the order called for the practices to be extended by example to high performing organizations responding to the difficult 21st century global workplace. As the incidences of racism and terrorism increase globally, they impact people transnationally through direct as well as vicarious traumatization. In order to respond effectively to ensure the safety of employees and organizations, EAPs must be staffed by mental health professionals and educational trainers who practice to enable cross-cultural understanding for the prevention of risk to employees and the organization. EAPs responding to emerging needs of global workplaces have a responsibility to adapt and innovate their programs and products in order to be effective. To add credibility to EAP services and add value to the Return-On-Investment (ROI) of such programs, connections can be made directly between theoretical underpinnings of EAPs and practical application through evidence-based practices (EBP) in organizations. The Evidence-Based System for Innovation Support (EBSIS) is a logic model proposed by Wandersman, Chien and Katz (2012) incorporating four elements (tools, training, technical Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs 10 assistance and quality assurance/quality improvement) interactively to achieve identified outcomes in programs, policies and processes. Needs assessment enables the determination of current capacity in organizations as well as identification of desired outcomes. According to the EBSIS model, a Getting To Outcomes (GTO) framework can be utilized to structure the evidence base from theory to evidence, practice and accountability. There are ten steps in the GTO which involve needs assessment, establishment of goals, identification of best practices, assessment for best fit, capacity concerns, development and implementation of plan, process evaluation, outcome evaluation, ingoing quality improvement, and sustainability issues (Wandersman, et al., 2012). This model can be effectively conceptualized for the development of EBP to enhance workplace adjustment and productivity through an inclusion of cultural competency in the services offered through EAPs. Gregory Jr., Van Orden, Jordan, Portnoy, Welsh, Betkowski, Charles, and DiClemente (2012) conducted a study incorporating cultural competence in an Interactive Systems Framework (ISF) with a purpose of innovative research and practice in human capacity building. Their research suggested that the ISF refers to the use of heuristic approaches to emergent prevention research. The authors presented a very succinct description of the ISF in terms of systemic interaction between dissemination of research for practical use, capacity building to facilitate innovation, and an evaluation of current use of innovation. Gregory Jr. et al. (2012) conducted a needs assessment of the agency that participated in the project to incorporate culturally competent innovative practices. An initial meeting discussed the objectives of the research and elicited areas for improved service delivery, which was attended by members of the leadership staff and stakeholders. The needs assessment was completed by the agency’s director and key administrative staff and included information regarding the agency’s organizational Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs 11 structure, clientele, screening and interventions practiced, standards of care, interest in training, staff capability, leadership style, organizational climate, and ongoing measures of quality improvement of programs. Optimizing the use of EBP was achieved by approaching the agency with feedback that was nonjudgmental and encouraging. Since it was a participatory action research, the feedback was disseminated in a collaborative manner, thereby facilitating ownership of innovations by the staff with the knowledge of EBPs and agency culture aiding the ongoing process of capacity building. Questionnaires and anonymous evaluations following trainings were one way the agency performed continuous evaluation. The success of such an interactive model is demonstrated by the effectiveness of disseminating EBPs that responded to the needs of the agency with innovations implemented and continuously evaluated for cultural competency. The model for capacity building strategies developed by Gregory Jr. et al (2012) can be adapted for the development of evidence-based cultural competency in EAP service. The model is adaptable for any organization that is contemplating innovation in services. Organizations can effectively reduce their healthcare costs and improve employee performance by providing preventative and proactive services using existing EAPs. Conducting a needs assessment would provide the basis for customizing services to suit the employee demographics of the organization and make effective use of human capital. Assessing utilization of existing services and innovations required would help organizations make optimal use of employee healthcare services, catering to emerging needs and reducing underutilized and perhaps obsolescent services. Responding to changing employee needs requires corporate commitment and responsibility and could ensure organizational accountability as well as employee loyalty and Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs 12 retention. The call for action to the EA industry as utilizing EBP through scientific research was articulated by Bennett, Bray, Hughes, Hunter, Frey, Roman and Sharar (2015). Organizations such as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) support a mission to build a Culture of Health for all Americans and the Foundation provides philanthropic support to communities, organizations, and business leaders to achieve social change by partnering with them (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2015). Organizations have a corporate social responsibility towards the health and well being of their employees. They are mandated to provide equal opportunities and desist from discriminatory practices based on gender, age, sexual orientation, and ability. However, organizational productivity can be enhanced by facilitating better employee-workplace adjustment, bridging the gap between services and their utilization, and by increasing inclusion practices through diversity training that is infused in the vision and mission of the organization, and practiced through existing employee assistance services using innovative models of human capacity building. In view of emerging needs, it would be a wise investment for the employee assistance industry to expand existing services to include the development and implementation of diversity training customized for organizational needs. More importantly, the EA profession would make a very prudent and salient ideological decision to incorporate the language of cultural responsiveness into the principles of EA Core Technology. Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs 13 References Attridge, M. (2012). Employee assistance programs: Evidence and current trends. In Handbook of occupational health and wellness (p. 441-467). Attridge, M. & Burke, J.(2011). Trends in EAP services and strategies: An industry survey. Employee Assistance Society of North America. Research Notes,4(3) Bennett, J., Bray, J., Hughes, D., Hunter, J., Frey, J.J., Roman, P., Sharar, D. (2015). Bridging public health with workplace behavioral health services. A framework for future research and a stakeholder call to action. Retrieved from http://www.eapassn.org/Portals/11/Docs/Newsbrief/PBRNwhitepaper.pdf Cross, T., Bazron, B., Dennis, K., & Isaacs, M. (1989). Towards a culturally competent system of care. Volume 1. Washington, DC: CASSP Technical Assistance Center, Center for Child Health and Mental Health Policy, Georgetown University Child Development Center. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED330171.pdf Department of Health & Human Services. Office of Minority Health (2015). HHS Action Plan to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities: Implementation progress Report 2011-2014. Retrieved from OMH website: http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/assets/pdf/FINAL_HHS_Action_Plan_Progress_Report_11 _2_2015.pdf Employee Assistance Professionals Association. (2010). EAPA standards and professional guidelines for employee assistance programs. Arlington, VA: Employee Assistance Professionals Association. Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs 14 Employee Assistance Professionals Association. (2010). Definitions of an Employee Assistance Program (EAP) and EAP core technology. Arlington, VA: Employee Assistance Professionals Association. Employee Assistance Society of North America (EASNA) (2009). Selecting and strengthening employee assistance programs: A purchaser’s guide. Arlington, VA. Employee Assistance Society of North America (EASNA) (2013). Retrieved from EASNA website: http://www.easna.org/research-and-best-practices/what-is-eap/ Employee Assistance Society of North America (EASNA) (2013). Retrieved from EASNA website: http://www.easna.org/research-and-best-practices/accreditation/accreditationoverview/ Egerter, S. Decker, M., An, J., Grossman-Kahn, R. & Braveman, P. (2008). Work matters for health. Work and Health, 4. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Commission on Health Futurework: Trends and challenges for work in the 21st century. (2000). Occupational Outlook Quarterly, 44(2), 31-36. Gregory Jr., H., Van Orden, O., Jordan, L., Portnoy, G. A., Welsh, E., Betkowski, J., Charles, J.W. & DiClemente, C. C. (2012). New directions in capacity building: Incorporating cultural competence into the interactive systems framework. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(3-4), 321-333. Kurzman, P.A. (2013). Employee assistance programs for the new millennium: Emergence of the comprehensive model. Social Work in Mental Health, 11, 381-403. doi: 10.1080/15332985.2013.780836. National Business Group on Health (NBGH) (2008). An Employer’s Guide to Employee Assistance Programs. US Dept. of Health and Human Services. Cultural Competence in the Core Technology of Employee Assistance Programs 15 National Center for Cultural Competence. Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development. (GUCCHD) (n.d.) Retrieved from http://nccc.georgetown.edu/foundations/frameworks.html Office of Minority Health. United States Department of Health & Human Services. National CLAS Standards. Retrieved from OMH website: http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlid=53 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2008). Work matters for health. Work and Health, 4 Retrieved from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation website: http://www.commissiononhealth.org/PDF/0e8ca13d-6fb8-451d-bac87d15343aacff/Issue%20Brief%204%20Dec%2008%20-%20Work%20and%20Health.pdf Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2015). Retrieved from: http://www.rwjf.org/ Sandys, J. E. (2012). The Evolution of External Employee Assistance Programs Since the Advent of Managed Behavioral Health Organizations (Doctoral dissertation, New York University). Steele, P. (1998). Employee assistance programs: Then, now, and in the future. In Center for Substance Abuse Prevention’s Knowledge Exchange Workshop, Tacoma, Washington. Steger, M.F.; Dik, B.J. & Duffy, R.D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3) 322-337. DOI:10.1177/1069072711436160 Wandersman, A., Chien, V.H. & Katz, J. (2012). Toward an evidence-based system for innovation support for implementing innovations with quality: Tools, training, technical assistance, and quality assurance/quality improvement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50 (445-459). DOI 10.1007/s10464-012-9509-7