Diverticulitis is an abscess or peridiverticular - Dis Lair

advertisement

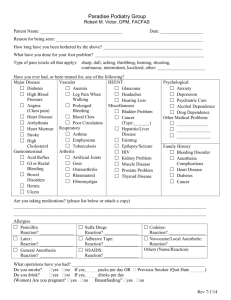

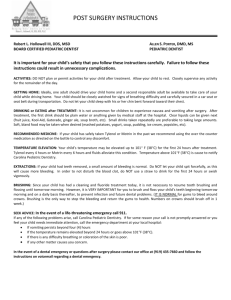

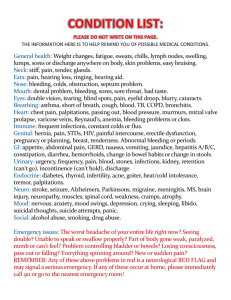

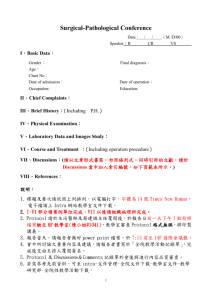

Diverticular Disease Introduction Background Diverticular disease is a common disorder, yet it was not recognized as a pathologic entity until the mid-19th century. Diverticulitisand lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding secondary to diverticulosis are the main complications of clinical importance to emergency physicians. Pathophysiology Diverticular disease may involve any part of the GI tract. Typically, acquired, diverticular disease may be congenital, such as Meckel's diverticulum (although this is rare). Diverticula are herniations of the mucosa and submucosa or the entire wall thickness through the muscularis (as seen in congenital diverticula). The sigmoid is the most commonly affected segment (95-98%); however, diverticular disease may also involve the descending, ascending, and transverse colon as well as the jejunum, ileum, and duodenum. The images below depicting sigmoid diverticulitis are of the same patient. Sigmoid diverticulitis in a 50-year-old man with history of diverticulosis and left lower abdominal pain and tenderness. This image and the images below are sections from the same patient. Sigmoid diverticulitis in a 50-year-old man with history of diverticulosis and left lower abdominal pain and tenderness. Phlegmon. Sigmoid diverticulitis in a 50year-old man with history of diverticulosis and left lower abdominal pain and tenderness. This image and the one below are consecutive sections of the same patient. Phlegmon. Sigmoid diverticulitis in a 50year-old man with history of diverticulosis and left lower abdominal pain and tenderness. Precise etiology of this disease is unknown. High intraluminal pressure and a weak colonic wall at the sites of nutrient vessel penetration into the muscularis may lead to herniation. The condition may also be caused by abnormal colonic motility, defective muscular structure, defects in collagen consistency (ie, increased cross-linking of collagen), and aging. Diverticulitis is an abscess or peridiverticular inflammation initiated by the rupture of a microscopic mucosal abscess into the mesentery. The infection may progress, fistulize, obstruct, or spontaneously resolve. Acute diverticulitis results from the inspissation of fecal material in the neck of the diverticulum and resultant bacterial replication. Infection is generally contained by pericolonic fat or adjacent organs, at which point a local phlegmon develops. Macroperforation may cause peritonitis and may erode locally. Lower GI bleeding from diverticulosis results from rupture of the small blood vessels that are stretched while coursing over the dome of the diverticula. Frequency United States Diverticular disease affects primarily those in developed countries. Eighty years ago, the approximate prevalence of diverticular disease was between 5% and 10%. A large study performed in 2002 of 9,086 consecutive patients undergoing colonoscopies revealed a prevalence of 27%, in which prevalence increased with age.1 International Diverticular disease has been dubbed the "disease of Western civilization." In developed countries, the rate of diverticular disease is between 5% and 45%, depending on age and sex. In Africa and Asia, the prevalence is around 0.2% and is typically right sided. Mortality/Morbidity Morbidity and mortality associated with diverticular disease is primarily related to acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding, diverticulitis, and perforated diverticulum. Fifteen percent of persons with diverticular disease will develop acute GI bleeding. Of those, one third will develop massive GI bleeding. Risk of mortality with perforated diverticulum increases with age, comorbid conditions, and onset of perforation within the first year of diagnosis. Studies have reported mortality rates between 22% and 39% for free perforation and fecal peritonitis. Furthermore, multiple series have noted that perforation may be the first manifestation of complicated diverticulitis with a range in mortality of 50-70%. Race Diverticular disease primarily affects those in developed countries. However, the incidence of diverticular disease is increasing in Asian countries. In Asian and African countries, the prevalence of diverticular disease is approximately 0.2% and predominantly on the right side. Sex Gender variation occurs by age group. Diverticular disease is more prevalent in men than in women younger than 50 years. Between the ages of 50-70 years, a slight female predominance exists. In those older than 70 years, there is a female predominance. Age The prevalence of diverticular disease increases with age: Less than 5% by age 40 years Approximately 30% by age 60 years 65% by age 85 years Clinical History 1. Clinical historical features of inflammatory disease include the following: Abdominal pain - Occurs mostly in the left lower quadrant and tends to be steady, severe, and deep History of fever suggestive of diverticulitis Previous episodes of dull, colicky, and diffuse abdominal pain accompanied with flatulence, distention, and change in bowel habits (diverticulosis) Altered bowel habits including diarrhea, increased constipation, and tenesmus (physician may note obstipation when treating a complicating bowel obstruction) Nausea and vomiting Dysuria, pyuria, and urinary frequency if bladder or ureter are irritated History of pneumaturia or recurrent urinary tract infections (colovesicular fistulas) Feculent vaginal discharge (fistulas with the uterus or vagina) Severe and generalized abdominal pain (diffuse peritonitis) Back or lower extremity pain (perforation) 2. Establish history of hemorrhagic disease, including the following: Lower GI bleeding from diverticulosis occurs in the form of bright red-colored or wine-colored stools. Onset of bleeding typically is sudden, painless, and accompanied by an urge to defecate. Amount of bleeding typically is massive and tends to stop spontaneously. Ascertain a previous history of gastric or duodenal ulcers, liver disease, or GI bleeding. Discomfort and pain upon defecation indicate hemorrhoids or anal fissures. History of weight loss and mucus in the stools indicates inflammatory bowel disease. Establish list of medications used (nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], steroids) and of alcohol abuse. Establish bleeding tendencies. Physical 1. Establish localized tenderness, rebound tenderness, and/or guarding. This is essential in the clinical management of diverticular disease. Their presence indicates diverticulitis. 2. When associated with GI bleeding, tenderness is not typical of diverticular etiology; it indicates other disease processes. 3. Assess vital signs to determine hemodynamic stability and profile of presentation. 4. Low-grade fever commonly is found in diverticulitis. 5. Rectal examination identifies tenderness, establishes the color of stools, and determines the presence and extent of GI bleeding. A mass may be seen in the cul-de-sac. 6. Diffuse abdominal tenderness, rebound, absent bowel sounds, and/or high-grade fever may be elicited. These indicate possible complications of perforation and/or peritonitis. 7. Pelvic and rectal examinations establish the correct diagnosis. 8. Palpate for any mass or fullness, particularly in the left iliac fossa. 9. Abdomen may be distended and tympanic. 10. Pain may be acute and located mainly in the left lower quadrant. Causes 1. Low-fiber diet is the highest risk factor for diverticular disease. Common in industrialized nations, a low-fiber diet forms low-bulk stool that leads to increased segmentation of the colon during propulsion, causing increased intraluminal pressure and formation of diverticula. 2. High fat and beef diets also cause diverticular disease, probably for the same reasons as above. 3. Genetic causes exist. Asians have right-sided diverticula preponderance. In westerners, diverticula develop mostly on the left side. 4. Aging leads to change in collagen structure such as increased cross-linking and acid solubility. 5. Colonic motility disorders are a cause. 6. Corticosteroid therapy but not nonsteroidal antiinflammatory therapy has recently been shown to increase the risk of diverticulitis.2 7. Colonic segmentation: Nonpropulsive contractions produce isolated segments or little chambers with high pressure within. 8. Defects in colonic wall strength can cause diverticular disease. Differential Diagnoses Abdominal Hernias Irritable Bowel Syndrome Abdominal Trauma, Blunt Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding Inflammatory Bowel Disease Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding, Surgical Treatment Adnexal Tumors Lymphogranuloma Venereum Appendicitis Mesenteric Artery Ischemia Cholangitis Ovarian Cysts Cholecystitis Ovarian Torsion Cholelithiasis Pancreatitis, Acute Syphilis Colon Cancer, Adenocarcinoma Inflammatory Disease Perforated Peptic Ulcer Crohn Disease Peritonitis and Abdominal Sepsis Duodenal Ulcers Proctitis and Anusitis Ectopic Pregnancy Chronic Mesenteric Ischemia Endometriosis Tuberculosis Endometritis Ulcerative Colitis Gastric Ulcers Urinary Tract Infection, Females Gastritis, Acute Urinary Tract Infection, Males Hemorrhoids Volvulus, Sigmoid and Cecal Acalculous Cholecystitis Intestinal Perforation intestinal irritation (ileus) and two thirds of visceral perforations (free air). Radiographs can identify volvulus, bowel obstruction, renal stones, and occasionally suggest the existence of intra-abdominal masses. Chest radiographs can identify free air to rule out perforation. Radiographs are shown below. o "Thumbprinting" (seen in left mid quadrant) on a plain abdominal radiograph (close-up image). o WorkupPelvic Laboratory Studies 1. Complete blood count: CBC identifies leukocytosis and/or a left shift in acute diverticulitis; however, 60% of patients may have a normal white blood cell count, particularly elderly and immunocompromised patients. Manage GI bleeding by establishing hematocrit. 2. Type and cross-match blood; also obtain coagulation and bleeding time profiles in patients with lower GI bleeding or frank peritonitis. 3. Urinalysis/urine culture: This identifies urinary tract infections and hematuria. It indicates existence of colovesicular fistulas or if diverticular disease is the etiology. 4. Serum electrolytes: In the absence of a prerenal picture, an elevated BUN/creatinine ratio indicates the presence of blood in the GI tract. 5. Lipase/amylase and liver function tests: These may help establish other etiologies or features in the presentation of abdominal pain. This is particularly important when patients present atypically (eg, steroid therapy, elderly patients, those with diabetes) or relatively late in the course of an inflammatory process with generalized tenderness or frank peritonitis. 6. Perform blood cultures if acute diverticulitis is suspected prior to infusion of empiric antibiotic therapy. Imaging Studies 1. Plain radiographs: An acute abdominal series, with flat and upright abdominal imaging, identifies signs of 2. o o o o Thickening of the bowel wall in the descending colon due to bowel edema can be seen in the left lower quadrant on this plain abdominal radiograph. Note the narrowed colonic lumen. Note the CT scan images in this article are from the same 62-year-old patient with diverticulitis. CT scan: This is the test of choice for acute diverticulitis. Look for diverticula, localized colonic wall thickening (>5 mm), abscesses, fistulas, and pericolic fat inflammation, and exclude other pathologies, such as a tubo-ovarian abscess or aortic or other vascular blood leakage. Administering rectal contrast with no intravenous contrast has been shown in one study to be equally as sensitive as CT scans where oral contrast was administered; however, the test of choice is a CT scan that includes intravenous and oral contrast. Ten percent of CT scans are unable to determine between diverticular disease and carcinoma. Other findings include the following: Thickened fascia, 78.9% Colonic diverticula, 84% Soft tissue masses representing phlegmon, pericolic fluid collections, representing abscesses, 35% Muscular hypertrophy, 26.3% o Arrowhead sign (focal thickening of colonic wall with an arrowhead-shaped lumen pointing to inflamed diverticula), 23.7% 3. Double-contrast enema: This is useful in the diagnosis of diverticulosis yet contraindicated in acute diverticulitis because of the fear of perforation, leak of barium and intestinal content, and subsequent severe peritonitis. 4. Water-soluble contrast enema: Water-soluble contrast is safe in intraluminal imaging and useful in the workup of patients with suspected diverticular disease. However, a prospective study in 2000 has shown CT scanning to have a 97% sensitivity rate as compared to 92% sensitivity rate for water-soluble contrast enema. CT scanning was also superior in detecting abscesses. 5. Ultrasonography: Ultrasonography is a noninvasive test used by a number of investigators and has been reported to have a specificity as high as 99.8%. 3 When using highresolution graded compression ultrasonography, a sensitivity of 85-98% has been reported and a specificity of 80-98%. Findings when used at the point of maximal tenderness can reveal bowel wall thickening of 4-5 mm, target appearance, and abscess formation. 6. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): MRI was evaluated in one study and found that it accurately identified diverticulitis in 10 out of 11 patients.4 Larger studies are needed to further evaluate the modality of MRI in aiding in diagnosis of diverticulitis. Procedures 1. Endoscopy: Endoscopy is useful in diagnosing diverticular disease and in establishing the source of lower GI bleeding. Endoscopy is avoided in acute diverticulitis because of the fear of perforation and peritonitis. A nasogastric tube is usually inserted first to exclude most upper GI causes of rectal bleeding. A 2000 study found that aggressive urgent colonoscopy performed by a dedicated endoscopy team with experience in interventional procedures uses colonoscopy as both a diagnostic measure and a therapeutic measure.5 2. Technetium-99m-blood cell scan: Technetium-99m labeled RBC scan has a sensitivity of 97%, specificity of 85%, and a positive predictive value of 94% to identify active bleeding at a rate of 0.1 mL/min.6 It does, however, have a poor ability to localize the source of bleeding. Follow with a selective mesenteric arteriogram to identify the source. Treatment Prehospital Care 1. Start intravenous fluids and oxygen, particularly during lengthy prehospital periods. 2. Scenarios that usually require mobilization of prehospital resources are severe abdominal pain, GI bleeding, or hemodynamic instability with a diagnosis that has not yet been established. Emergency Department Care 1. When a patient presents with classic signs and symptoms of uncomplicated diverticulosis, discharge on antispasmodics and a high-fiber diet with a follow-up sigmoidoscopy at a later time. Typically, no fever, leukocytosis, palpable mass, or other evidence of acute diverticulitis is present. 2. For patients who present with signs and symptoms of acute diverticulitis, take the following actions: Administer intravenous fluid resuscitation as indicated. Give the patient nothing by mouth (NPO). In a recent retrospective study, patients who underwent surgical therapy after an initial episode of acute diverticulitis had less recurrence than those who were managed medically. Analgesic pain control should be given. Although studies have indicated that analgesics do not mask peritoneal signs, consider general surgery consultation prior to analgesic pain control. Insert a nasogastric tube if the patient is vomiting or colonic obstruction is suspected. Administer empiric broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics. Antibiotics should target anaerobes such as Bacteroides fragilis and Peptostreptococcus, Peptococcus, and Clostridium species, as well as aerobes such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella, Proteus, Streptococcus, and Enterobacterspecies. If an abscess is suspected, coverage also should include Pseudomonas aeruginosa. 3. Most patients diagnosed with acute diverticulitis should be hospitalized; most improve in 48-72 hours. 4. Patients with mild-to-moderate acute diverticulitis and no systemic signs or localized peritonitis may be discharged home on a low-residue food diet and oral antibiotics covering gram-negative organisms and anaerobes. Instruct patients to return if the pain increases or signs of systemic infection develop, assuming the patient is a normal host with no clinical evidence of other morbid conditions requiring admission or additional workup. 5. Perform the following if the patient presents with signs and symptoms of acute GI bleeding: Address standard ABCs appropriately. Administer supplemental oxygen. Maintain hemodynamic stability. Secure 2 large-bore IV lines. Administer lactated Ringer or normal saline solution. Once 2 liters of intravenous fluids are administered, transfuse blood. Insert a nasogastric tube to exclude potential upper GI source for the bleeding. Search for comorbid conditions such as an acute myocardial infarction from the hypovolemic state. Insert a urinary catheter to monitor output, which reflects adequacy of resuscitation. Secure the appropriate emergent consultations quickly. Admit the patient to an intensive care setting. 6. Subsequent management centers on identifying the source of bleeding. 7. Diagnosis and treatment guidelines for sigmoid diverticulitis are available from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.7 Consultations Consult with a general surgeon if the patient presents with any of the following: 1. Sepsis, fistula, or obstruction 2. Clinical evidence of perforation of viscus 3. Failure of medical therapy or clinical deterioration 4. Inability to exclude carcinoma or recurrence of the disease 5. Young age, use of steroids, immunocompromised patients, and right-sided diverticulitis (relative indications for surgical intervention) Consult for further workup and management as well as the arrangement of follow-up colonoscopy. Medication Goals of pharmacotherapy are to treat the infection and prevent complications. Organisms that should be covered by antimicrobial therapy include the following: 1. Anaerobes -Bacteroides fragilis, Peptostreptococcus, Clostridium species 2. Aerobes -Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Proteus, Streptococcus, Enterobacter organisms Typical antimicrobial therapy is divided into inpatient and outpatient regimens. 1. Outpatient therapy (one of the following): Metronidazole plus ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin or TMP/SMX Amoxicillin/clavulanate Moxifloxacin 2. Inpatient therapy - Mild-to-moderate disease (one of the following): Metronidazole plus ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin (intravenous) Ampicillin/sulbactam Ertapenem Piperacillin/tazobactam Ticarcillin/clavulanate Tigecycline 3. Inpatient therapy - Severe disease (one of the following): Imipenem Doripenem Meropenem Ampicillin plus metronidazole plus ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin or gentamicin 4. For penicillin-allergic patients: Metronidazole plus aztreonam or ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin Antibiotics Therapy should cover all likely pathogens in the context of the clinical setting. Ciprofloxacin (Cipro) Fluoroquinolone that inhibits bacterial DNA synthesis and, consequently, growth, by inhibiting DNA gyrase and topoisomerases, which are required for replication, transcription, and translation of genetic material. Quinolones have broad activity against gram-positive and gram-negative aerobic organisms. Has no activity against anaerobes. Continue treatment for at least 2 d (7-14 d typical) after signs and symptoms have disappeared. Adult 500 mg or 750 mg PO bid 400 mg IV bid Pediatric <18 years: Not recommended >18 years: Administer as in adults Amoxicillin and clavulanate (Augmentin) Amoxicillin inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis by binding to penicillin-binding proteins. Addition of clavulanate inhibits beta-lactamase producing bacteria. Good alternative antibiotic for patients allergic or intolerant to the macrolide class. Usually well tolerated and provides good coverage to most infectious agents. Not effective against Mycoplasma and Legionella species. Half-life of oral dosage form is 1-1.3 h. Has good tissue penetration but does not enter cerebrospinal fluid. For children >3 months, base dosing protocol on amoxicillin content. Because of different amoxicillin/clavulanic acid ratios in 250-mg tab (250/125) vs 250-mg chewable-tab (250/62.5), do not use 250-mg tab until child weighs >40 kg. Adult 500-875 mg PO q12h or 250-500 mg PO q8h for 7-10 d Pediatric <3 months: 125 mg/5 mL PO susp; 30 mg/kg/d (based on amoxicillin component) divided bid for 7-10 d >3 months: If using 200 mg/5 mL or 400 mg/5 mL susp, 45 mg/kg/d PO divided q12h; if using 125 mg/5 mL or 250 mg/5 mL susp, 40 mg/kg/d PO divided bid for 7-10 d >40 kg: Administer as in adults Ertapenem (Invanz) Bactericidal activity results from inhibition of cell wall synthesis and is mediated through ertapenem binding to penicillin-binding proteins. Stable against hydrolysis by a variety of beta-lactamases including penicillinases, cephalosporinases, and extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Hydrolyzed by metallo-beta-lactamases. Adult 1 g qd for 7- 14 d if IV; infuse over 30 min if IV CrCl <30 mL/min/1.73 m2: 500 mg IV qd Pediatric <3 months: Not established 3 months to 12 years: 15 mg/kg IV q12h; not to exceed 1 g/d >12 years: Administer as in adults Gentamicin sulfate Aminoglycoside antibiotic for gram-negative coverage bacteria including Pseudomonas species. Synergistic with beta-lactamase against enterococci. Interferes with bacterial protein synthesis by binding to 30S and 50S ribosomal subunits. Dosing regimens are numerous and are adjusted based on CrCl and changes in volume of distribution, as well as body space into which agent needs to distribute. Dose of gentamicin may be given IV/IM. Each regimen must be followed by at least trough level drawn on third or fourth dose, 0.5 h before dosing; may draw peak level 0.5 h after 30min infusion. Adult 5 mg/kg IV/IM qd Pediatric <5 years: 2.5 mg/kg/dose IV/IM q8h >5 years: 1.5-2.5 mg/kg/dose IV/IM q8h or 6-7.5 mg/kg/d divided q8h; not to exceed 300 mg/d; monitor as in adult Tigecycline (Tygacil) A glycylcycline antibiotic that is structurally similar to tetracycline antibiotics. Inhibits bacterial protein translation by binding to 30S ribosomal subunit, and blocks entry of amino-acyl tRNA molecules in ribosome A site. Complicated intra-abdominal infections caused by C freundii, E cloacae, E coli, K oxytoca, K pneumoniae, E faecalis (vancomycinsusceptible isolates only), S aureus (methicillin-susceptible isolates only), S anginosusgroup. (includes S anginosus, S intermedius, and S constellatus), B fragilis, B thetaiotaomicron, B uniformis, B vulgatus, C perfringens, and P micros. Adult Infuse each dose over 30-60 min 100 mg IV once, then 50 mg IV q12h Severe hepatic impairment (ie, Child Pugh class C): 100 mg IV once, then 25 mg IV q12h Pediatric <18 years: Not established >18 years: Administer as in adults Imipenem and cilastatin (Primaxin) For treatment of multiple organism infections in which other agents do not have wide-spectrum coverage or are contraindicated due to potential for toxicity. Adult Base initial dose on severity of infection, and administer in equally divided doses; dose may range from 250-500 mg q6h IV for a maximum of 3-4 g/d Alternatively, 500-750 mg q12h IM or intra-abdominally Pediatric Infants >3 months and children <12 years: 15-25 mg/kg/dose IV q6h Fully susceptible organisms: Not to exceed 2 g/d Infections with moderately susceptible organisms: Not to exceed 4 g/d >12 years: Administer as in adults Doripenem (Doribax) Carbapenem antibiotic. Elicits activity against a wide range of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Indicated as a single agent for complicated intra-abdominal infections caused by susceptible strains of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacteroides caccae, Bacteroides fragilis, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Bacteroides uniformis, Bacteroides vulgatus, Streptococcus intermedius, Streptococcus constellatus, and Peptostreptococcus micros. Adult 500 mg IV q8h infused over 1 h CrCl> 50: No dosage adjustment necessary CrCl≥ 30 to ≤ 50: 250 mg IV q8h CrCl> 10 to < 30: 250 mg IV q12h Pediatric <18 years: Not established >18 years: Administer as in adults Aztreonam (Azactam) A monobactam, not a beta-lactam antibiotic that inhibits cell wall synthesis during bacterial growth. Active against gramnegative bacilli but very limited gram-positive activity and not useful for anaerobes. Lacks cross-sensitivity with beta-lactam antibiotics. May be used in patients allergic to penicillins or cephalosporins. Duration of therapy depends on severity of infection and continued for at least 48 h after patient asymptomatic or evidence of bacterial eradication obtained. Doses smaller than indicated should not be used. Transient or persistent renal insufficiency may prolong serum levels. After initial loading dose of 1 or 2 g, reduce dose by one half for estimated ClCr of 10-30 mL/min/1.73 m2. When only serum creatinine concentration available, the following formula (based on sex, weight, and age) can approximate ClCr. Serum creatinine should represent a steady state of renal function. Males: ClCr = [(weight in kg)(140 - age)] divided by (72 X serum creatinine in mg/dL) Females: 0.85 X above value In patients with severe renal failure (ClCr <10 mL/min/1.73 m2), those supported by hemodialysis, usual dose of 500 mg, 1 g, or 2 g, is given initially. Maintenance dose is one fourth of usual initial dose given at usual fixed interval of 6, 8, or 12 h. For serious or life-threatening infections, supplement maintenance doses with one-eighth of initial dose after each hemodialysis session. Elderly persons may have diminished renal function. Renal status is a major determinant of dosage in these patients. Serum creatinine level may not be an accurate determinant of renal status. Therefore, as with all antibiotics eliminated by kidneys, obtain estimates of ClCr, and make appropriate dosage modifications. Insufficient data are available regarding IM administration to pediatric patients or dosing in pediatric patients with renal impairment. Administered IV only to pediatric patients with normal renal function. Adult 500-2000 mg IV/IM q6-8h Pediatric 90-120 mg/kg/d IV/IM divided q6-8h Metronidazole (Flagyl) Active against various anaerobic bacteria. Enters cell, binds DNA, and inhibits protein synthesis, causing cell death. Adult 500 mg PO/IV qid Pediatric <12 years: Not established >12 years: Administer as in adults Piperacillin and tazobactam sodium (Zosyn) Antipseudomonal penicillin plus beta-lactamase inhibitor. Inhibits biosynthesis of cell wall mucopeptide and is effective during stage of active multiplication. Adult 3/0.375 g (piperacillin 3 g and tazobactam 0.375 g) IV q6h Pediatric <12 years: Not established >12 years: Administer as in adults Levofloxacin (Levaquin) For pseudomonal infections and infections due to multidrug resistant gram-negative organisms. Adult 500-750 mg PO/IV qd for 7-14 d Pediatric <18 years: Not recommended >18 years: Administer as in adults Moxifloxacin (Avelox) Inhibits the A subunits of DNA gyrase, resulting in inhibition of bacterial DNA replication and transcription. Adult 400 mg PO/IV qd Pediatric <18 years: Not recommended >18 years: Administer as in adults Ticarcillin and clavulanate potassium (Timentin) Inhibits biosynthesis of cell wall mucopeptide and is effective during stage of active growth. Antipseudomonal penicillin plus beta-lactamase inhibitor that provides coverage against most gram-positive organisms, most gram-negative organisms, and most anaerobes. Adult 3.1 g IV q4-6h Pediatric 75 mg/kg IV q6h Meropenem (Merrem I.V.) Bactericidal broad-spectrum carbapenem antibiotic that inhibits cell wall synthesis. Effective against most grampositive and gram-negative bacteria. Has slightly increased activity against gram-negatives and slightly decreased activity against staphylococci and streptococci compared with imipenem. Adult 1 g IV q8h Pediatric 40 mg/kg IV q8h Ampicillin (Principen) Broad-spectrum penicillin. Interferes with bacterial cell wall synthesis during active replication, causing bactericidal activity against susceptible organisms. Alternative to amoxicillin when unable to take medication orally. Until recently, the HACEK bacteria were uniformly susceptible to ampicillin. Recently, however, beta-lactamase– producing strains of HACEK have been identified. Adult 2 g IV q6h; not to exceed 12 g/d Pediatric 50-100 mg/kg/d PO divided q4-6h 100-400 mg/kg/d IV/IM divided q4-6h Follow-up Further Inpatient Care 1. Modalities used to stop bleeding include the following: Intra-arterial vasopressin Embolization was successful in 85% of cases based on a recent meta-analysis. Endoscopic homeostasis by epinephrine injection, heater probe, or bipolar coagulation 2. If bleeding persists or clinical condition does not permit the above modalities, perform emergency surgery. Further Outpatient Care 1. If the patient is not admitted and the diverticular disease episode resolves, arrange for colonoscopy and/or barium contrast enema. 2. Recommend a fiber-rich diet. Transfer 1. Transfer patients if the medical center has no general surgeons or radiologic facilities. 2. Do not transfer patients with active GI bleeding and impending or actual peritonitis. Deterrence/Prevention 1. High-fiber diet 2. Psyllium 3. Agar 4. Methylcellulose Complications 1. Fistulas Fistulas occur secondary to chronic diverticulitis or recurrent episodes of acute diverticulitis. Chronic inflammatory process causes adhesions to form between the colon and neighboring organs. Colovesicular fistulas are the most common (most occur in men), followed by colovaginal fistulas (80% occur in women who have undergone hysterectomies). Additionally, fistulas to the integument, uterus, fallopian tubes, and pelvic floor have been reported. Contrast enemas, retrograde dye studies, or CT scan confirms the diagnosis. Treatment of fistulas consists of surgical resection of the involved colon. 2. Hemorrhage 3. Perforation with peritonitis Clinical presentation typically is more severe than in acute diverticulitis. It often is diagnosed by observing free air on plain radiographs. Barium enemas and endoscopy are contraindicated. Treat surgically. Laparoscopic resection has comparable results to open resections when performed in experienced institutions. 4. Abscess o Suspect abscess when the patient fails to respond to medical therapy. It may be palpable. o CT scan or ultrasonography typically permits diagnosis of abscess. o Treat with percutaneous drainage. Some report successful transrectal and transvaginal drainage in selected situations. 5. Colonic obstruction o Colonic obstruction results from repetitive episodes of diverticulitis that cause mycosis coli or colonic muscular wall thickening. o Differentiate from other causes of obstruction, such as ischemia, colitis, or carcinoma, by contrast enemas or endoscopy. o If diagnosis is uncertain or obstructive symptoms develop, perform resection. Prognosis The Hinchey staging system reflects surgical outcome. It guides surgeons in selecting their operative strategy and reflects the risk of secondary complications after the acute episode is managed successfully. o Stage I - Pericolic abscess o Stage II - Pelvic abscess o Stage III - Purulent peritonitis o Stage IV - Feculent peritonitis Stage I disease treated by primary resection has 0% mortality, while stages II and III have 5% and 18% mortality, respectively. Prognosis is good with early detection and treatment of complications. Of those with a first episode of diverticulitis who successfully are treated medically, 67% do not have subsequent attacks requiring hospitalization, and 33% have recurrences; 2-3 recurrences in 1-2 years is an indication to electively remove the involved segment of colon. Of those with diverticular bleeding, as many as 20% rebleed within months to years. Miscellaneous Medicolegal Pitfalls Failure to promptly initiate empiric antibiotic therapy with clinically evident diverticulitis Failure to promptly diagnose visceral perforation or peritonitis Failure to adequately treat patients younger than 40 years Failure to appreciate that right lower quadrant pain in an elderly patient or a premenopausal woman may be caused by acute diverticulitis Special Concerns Hemorrhage secondary to diverticulosis in elderly persons carries a worse morbidity and mortality. A Comparison of Laparoscopic Sigmoid Resection and Open Sigmoid Resection in Managing Diverticular Disease Summary How does laparoscopic sigmoid resection (LSR) compare with open sigmoid resection (OSR) in managing diverticular disease? The authors conducted a trial with 52 patients randomized into each group. The operating time for LSR was about an hour longer than that with OSR. The results were similar with respect to overall complication rate; however, major complications such as leakage, bleeding, and abscess formation were more frequent in the OSR group (P = .038). Patients in the LSR group returned home earlier and had less postoperative pain. Viewpoint This report found that LSR is at least as good as and possibly better than OSR in managing diverticular disease that requires surgery. The quality-of-life score was improved in the LSR group, although it is possible that some patients knew which operation had been performed despite the covered incisional area. A larger trial might have demonstrated a significant reduction in overall postoperative complications in the LSR group.