ICMRP-14-148 - Global illuminators

advertisement

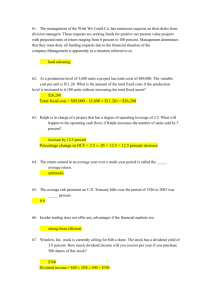

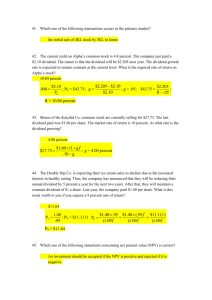

2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. IMPACT OF INSTITUTIONAL OWNERSHIP ON STRATEGIC DECISIONS: AN ANALYSIS OF NON-FINANCIAL SECTOR OF PAKISTAN Sadaf Rabeea Mohammad Ali Jinnah University Correspondence: rabeeasadaf1212@yahoo.com ABSTRACT This study investigates the relationship between institutional ownership and firm’s strategic decisions. These strategic decisions include, leverage or capital structure decisions, dividend decisions and investment decisions. Using industry level data of 170 non- financial firms (belonging to eight different sectors during a time period of 2003-2011) of Pakistan, characterized by a large percentage of institutional investors having multiple equity stake in different firms across a wide spectrum of industries, this study shows the two novelties. First the previous studies have identified the impact of institutional ownership on individual strategic decisions; dividend or leverage. This study however explores the impact that institutional ownership collectively has on various strategic decisions of firm. Secondly, this study recognizes the joint determination of strategic decisions by considering the endogenity among them. The issue of endogenity is addressed by considering a system of equations using Three stage least Square (3SLS). The findings suggest a collective two way relation between leverage, dividend and investment decisions. The study reports that firms with large institutional ownership have a significant adverse impact on the leverage or capital structure decisions. However this study does not find significant evidence for the relationship that institutional ownership exerts on dividend decisions and investment decisions. Keywords: Institutional Ownership, Strategic Decisions, 3SLS, Endogenity. 1. INTRODUCTION The traditional view of corporation, as argued by Berle and Means (1932), is characterized by ownership that is widely spread between many small shareholders, yet control is concentrated in the hands of few managers. This ownership structure creates in the conflict of interest between managers and shareholders and results in agency problem (Fama, 1980; Fama & Jensen, 1983). The empirical studies have shown that ownership of firms in many countries of the world is typically concentrated in the hands of a small number of large shareholders (La Porta et al., 1999; Barca and Becht, 2001). This ownership structure leads towards an equally important agency conflict between large controlling shareholders and minority shareholders. On the one hand, large shareholders can benefit minority shareholders by their role in monitoring managers (Shleifer and Vishny, 1986, 1997). These large shareholders can be dangerous if they hunt for their private goals (Shleifer and Vishny, 1997; and Burkart et aI., 1997). Institutional ownership is defined in literature as the percentage of firm’s shares that is owned by institutional investors. Institutional ownership can also be defined as “one minus percentage of shares held by individual investors” (Chung and Zhang, 2002). Institutional investors serve to monitor the firms in which they invest. This means that these investors have a due concern related to management of firm and its various strategic decisions. The purpose of this study is to find out the relation that institutional ownership has on firms’ strategic decisions about leverage or capital structure, dividend decision and decision related to investment. Literature provides evidence about a number of studies stressing the importance of institutional investor in the strategic decisions of the firms. The decisions include investment decisions (Cul and Xu, 2005; Kochhar and David, 1996), dividend policy decisions (Jain, 2007; Rubin and smith, 2009; Chen et al., 2005; Afza and Hassan, 2011; Gharaibeh et 1 2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. al., 2013; Azzam, 2010; Mitton, 2004) and leverage or capital structure decisions (Najjar and Taylor, 2008; Bokpin and Akro, 2009; Li et al., 2009; Jiraporn et al., 2012). The dependence of strategic decisions on each other creates a problem of endogenity. This leads to two way causal relationship between them. Leverage or capital structure decisions are affected by dividend decisions (Najjar, 2009) and dividend decisions are also have an impact by leverage of firm (Asif et al., 2011). This study provides additional evidence on the relationship among firms’ strategic decisions and ownership by institutions using a dataset from developing economy of Pakistan. In order to capture endogenity problem, this study has incorporated an advanced empirical technique to provide a more strong explanation of the endogeneity issue on the relationship among firm’s strategic decisions. Three Stage-Least Square technique provides us more robust result because it captures cross equation impact of endogenous and exogenous variables. The theoretical support for the relationship between institutional ownership and its impact on the strategic decision and ultimately firm value is based on different arguments namely “monitoring hypothesis”, “Strategic alignment” and “conflict of interest” hypothesis. Monitoring hypothesis (Shleifer et al., 1968) is based on agency theory perspective. It states that a higher ownership concentration allows a firm to make better and accurate strategic decision because of institutional expertise and a high level of information gathering, processing and correcting skills. Institutions that have a large stake in firm have more ability and incentive to monitor the firm. Strategic alliance (Pound, 1988) hypothesis state that a higher ownership concentration can cause problems and reduces firm value by creating an agency issue among institutional and individual equity holders. Small shareholders are hence harmed and decision making is hijacked by institutional owners. The conflict of interest hypothesis proposes that a higher concentrated ownership will compel the institutional owner in the favor of manager and hence their votes are biased for the managers for obtaining own benefits. Research Questions 1. How institutional ownership affect the leverage decisions of firms in Pakistan? 2. What is the impact of institutional ownership on firms’ dividend decisions in Pakistan? 3. Does institutional ownership influence the firms’ investment decisions in Pakistan? 2. LITERATURE REVIEW The concept of ownership and management of firm as separate entity was introduced by Berle and Means (1932) that provide a foundation to agency theory. According to agency theory, the firm is owned and managed by two different parties; owners (principal) and managers (agents). This agency relationship is characterized by allocation of some power to agents (managers). Since both parties have their own interest, that is the why the managers least act in the way that is demanded by owners (Jensen and Meckling, 1976).The situation becomes worse when the ownership disperses; the ability to exercise ownership rights also disperses (Walsh & Seward, 1990 According to Shleifer and Vishny (1986) concentrated owners have a remarkable affinity to managers’ monitoring and controlling in contrast to those board of directors having little or no investment in company. These owners have sufficient resources in comparison with small investors. Due to their monitoring activities, managers are compelled to do what is best for individual as well as large owners (Agrawal and Mandelker, 1992). In spite of the benefits, controlling by owners has some costs too. This type of owners some time values their own benefits at the expense of firm value and profitability. So it will give harm to other shareholders of firm. Many studies report negative relationship between controlling owners and firm value and profitability (Thomsen et al., 2006) and this result into conflict of interest between them. Moreover, these owners enjoy their control over firm decisions even when they are incompetent to do so (Shleifer and Vishny, 1997). Besides monitoring role, institutional 2 2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. investors are said to be ‘better informed investors’ as compared to other owners because they have to bear low average cost to acquire better and accurate information. So these investors are more efficient and enjoy economies of scale in information gathering and processing than other retail investors. Yan and Zhang (2009) study the role of information of different types of institutional owners. They argue that in spite of commonalities; institutional investors are no more homogenous. They are heterogeneous because of their varying investment horizons: and also because of their difference in their informational roles. Various studies are of view that institutions that trade very often due to their informational gain (Wermers, 2000) or overconfidence (Barber and Odean, 2000) are termed as short term institutions. On the other hand, those institutional owners who possess limited information behave carefully (Yan and Zhang, 2009). Boehmer et al., (2005) report that greater institutional ownership is related with improved efficiency of price information. So the institutional investment in firm improves firm’s informational climate. Burns et al., (2010) conduct a study on institutional ownership and financial misreporting. Using data of US companies, it finds that financial misreporting and institutional ownership are positively related due to ownership of institutions having short investment horizon. Institutional ownership is active player for monitoring firms’ different activities. In a recent study conducted in China, Aggarwal et al., (2013) report the association between institutional ownership and financial fraud. This study finds that firms with higher mutual fund ownership have lesser incidences of fraud. There is not any comprehensive theoretical support to leverage of firm but there are certain conditional arguments (Myers, 2001). The capital structure debate is attributed to Modigliani and Miller (1958, 1963). According to this study, the value of firm is not affected by the source used by it to for financing; whether debt or equity. This study results into two main capital structure theories include trade-off theory (Modigliani and Miller, 1963 and Jensen and Meckling, 1976) and the pecking order theory (Myers and Majluf, 1984). The tradeoff theory states that a firm will consider it financing decisions by evaluating marginal cost and benefits associated with them. Pecking order theory states that there is a pecking and order in the use of internal to external funds. The firm will prefer internal funds to external debt. When firm needs more funds, it borrow from outside and gain the benefits of low informational cost. The previous literature reports mixed evidence on ownership and capital structure relations. Changhati and Damanpour (1991) report that the level of institutional investment has a significant relation with firm’s leverage and return on equity: larger institutional ownership means low degree of indebtedness. Najjar and Taylor (2008) in their work on ownership and capital structure of Jordanian firms and report no clear evidence of firm’s capital structure choices, nor any significant relationship of firm’s ownership and leverage. In a study on capital structure and ownership, Sheikh and Wang (2012) argue that there is a positive relation between leverage and concentrated ownership in the case of Pakistani firms listed at KSE. This positive relationship confirms the monitoring of large shareholders to make them act in the way that is in best interest of blockholders and small owners as well. A negative relation between leverage and institutional holdings is found by Michaely and Vincent (2013). This study argues that firms having higher level of institutional ownership are low leveraged. This means that a change in institutional ownership causes an opposite change in leverage of firm. H1: The degree of stock ownership by outside institutions is negatively related to the debtto-equity ratio of the firm The research in the domain of firm payment and dividend policy become a puzzle Since Miller and Modigliani (1961) finds that a firm value is not affected by its dividend policy. The dividends payment reduces agency conflicts and arising agency cost between firm’s management and its owners. Rozeff (1982) observes that high dividend paying firms face low agency costs. The study attempts to optimize the dividend payout by considering two market 3 2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. imperfections; agency cost of debt and transaction cost related to issuing external finance. Increased dividend lowers agency cost of debt but increases the transaction cost of external financing. These two costs are used simultaneously to determine optimal dividend payout. In a research conducted by Truong and Heaney (2007), the results report that firms pay more dividends when profitability increases and firm has lesser investment opportunities. The results of this study are consistent with previous studies. Grinstein and Michaely (2003) find that repurchases increases with the increase in firm’s institutional ownership. According to their findings, the results suggest that institutions give more preference to firms that repurchase more. In developing economy of Egypt, Abdelsalam et al., (2008) link governance and firm’s dividend policies to discuss in the case of a rising economy of Egypt. The results provide strong support for the positive association between firm’s dividend policy and firm performance. This study also reports a significant association between the firm’s dividend and institutional shareholding. Najjar (2009) employ Pooled Panel Tobit and Logit model to examine the impact of dividend behavior in Jordan firms. The dividend payout ratio is the dependent variable in this study and it is in the form of dummy variable. This study report that there is not any significant difference between the developed and developing market for the factors determining the firms’ dividend policy such as capital structure, institutional shareholding, profitability, business risk, asset structure, growth rate and firm size. This study reports partial negative relationship of corporate dividend payout and its proportion of shares owned by institutional owners. In a research on developing market Shah et al. (2011) investigate the relationship of dividend policy of firms in relation to their ownership structure. This study report that dividend payment level increases with the rise of ownership by insiders. Moreover, the study also reports a positive relation of managerial ownership and firm dividend payment. H2: The percentage of stock ownership by outside institutions is positively related to the dividend payment of the firm Academic literature and studies claim institutional investors to have an excessive focus on short term earnings leading firms’ managers to make decisions enhancing short term earnings at the cost of firm long term goals and value. This claim is attributed to short term performance pressure that leads some institutional investors to rely on short term earning performance and overall shortsightedness on current earnings (Porter, 1992). Bushee (2001) classifies institutional investor’s preference for long term or short term earnings of firm on the basis of their investment horizon and fiduciary standards that are being faced by these institutional investors. The institutional investors having short term focus and invest on the basis of short trading profit are termed as ‘Transient institutions’. These institutions are the main trigger of managerial myopic behavior. The other two types of institutions are “dedicated” and “quasiindexer”. These two types of institutions have stable, longer term ownership and are less focused on short-term earnings (Bushee, 1998). On the basis of fiduciary requirements, nearterm earnings are preferred by those institutions having strict standards (banks) and those having fairly relaxed fiduciary standards mostly value long term earnings or capital gains (Bushee, 2001). Critics of this view point argue that if investors are not valuing long term investment horizon, they are lowering their expected earnings (Jenson, 1988). Contrary to myopic investment hypothesis, ‘superior investor hypothesis ’proposes that large institutional owners are intended to analyze the information prior to any decision making. Barber and Odean (2008) use attention based model of decision making in the context of common stock purchases. Choosing a common stock to buy presents investors with a huge set of possibilities. When selling, they argue, most investors consider only stocks they already own or those stocks that have recently caught their attention; an investor is less likely to purchase a stock that is out of the limelight. Consistent these predictions, they find that individual investors display 4 2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. attention-based buying behavior. The institutional investors, on the other hand, are the value strategy investors; they do not display attention-based buying. H3: The percentage of stock ownership by outside institutions is negatively related to the investment of the firm 3. DATA AND RESEARCH METHODOLOGY Data type used for this study is secondary. The secondary data has been collected from Balance Sheet Analysis publication of State Bank of Pakistan, annual reports of companies, business recorder and Karachi Stock exchange website. The time period of this study is comprised of 09 years; from 2003-2011.The selection of companies depends upon availability of the data. Financial firms, firms with negative equity and the firms whose relevant data is incomplete or not available are excluded from this study. The sample includes 170 non-financial firms listed in Karachi Stock Exchange and grouped under 8 different sectors. The final sample comprises of 170 firms distributed across eight different sectors as follows: Engineering (12), Chemical (25), Construction & Material (13), Paper & board (5), Fuel & Energy (9), Food Producers (32), Personal Goods (66), Others (8). Personal goods and food producer companies together make above 50% of sample. Measurement of Variables Leverage Leverage is measured by either debt to equity ratio or debt to assets ratio (Hassan and Butt, 2009: Lee and Kuo, 2013). This study preferably uses debt to equity ratio as it is being reported in State Bank of Pakistan publication of Balance Sheet Analysis. Dividend The dividend decision of firm is captured by dividend yield. It is measured as the ratio of dividend per share to the market price per share (Han et al., 1999: Asif et al., 2010). Investment This study capture the relationship of institutional ownership and investment decision by using the ratio of Change in Fixed Assets to Total Assets as the investment decisions of firms have a long term focus. Institutional Ownership Institutional ownership would be quantified as percentage of shares owned by institutional investors to the total number of share outstanding (Michaely and Vincent, 2013). Profitability Profitability of firm can be measured either by using Return on Assets or by using Return on Equity ratio. This study measures the profitability by using Return on Equity (Bhattacharya and Graham, 2007; Hillman, 2003). Return on Equity is the ratio of net income to shareholders’ equity. Size Of Firm The other important explanatory variable is size of firm (Schuler, 1996). In order to quantify the size of firm, the natural logarithm of book value of total assets is used. The same measure was used by Lin and Chang (2011). Tangibility Tangibility of assets is measured as the ratio of fixed assets to the total assets of firm (Liu et al., 2011). Sales Growth Sales growth is the rate at which a firm is growing annually. Sales growth is calculated as the annual percentage change in sales of a company (Lin and Chang, 2011). It is the difference between sales in the current year and the sales in the previous year divided by the previous year's sales. 5 2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Age of Firm Firm age seems to influence the decisions related to leverage, dividend and investment. Firm age is defined as the number of years elapsed since a firm was listed (Lev and Nissin, 2003). Methodology In method identified for this study, there is a potential causality or endogenous relationship among leverage decisions, dividend decisions and investment decisions. A simple OLS estimation to capture the relationship among variables would create biased and inconsistent estimates as given by Demsetz and Villalonga (2001) and Cho (1998). So there is a need to explore a more sophisticated technique for estimation. There are different ways to address the issue of biased and inconsistent estimate. One is 2SLS and other is 3SLS and GMM. The main difference between 2SLS and 3SLS is that in 3SLS, we are able to capture cross equation impacts of error terms and system of equation is supposed to be correlated in 3SLS. 3SLS is most appropriate technique for this data set because of the fact that some institutions have a multiple ownership stake in different firms. So ownership and strategic decision making can affect each other in many ways. 3SLS is a system that is designed to capture a relation where equations in model have endogenous variables as exogenous. Since some of the explanatory variables are endogenous variables in system, so error terms of the equations are correlated which simply violates the assumptions of Ordinary Least Square (Chichernea et al., 2012). We can estimate the relationship as, LEVt = β0 + β1 ROEt+ β2 SALESGRt + β3 SIZEt+ β4 TANGt + β5 INSTt + β6 DPOt + ε1 3.1 DYt = β0 +β1 ROEt + β2 SALESGRt +β3 SIZEt + β4 TANGt + β5 INSTt + β6 LEVt +ε2 3.2 INVt = β0 + β1 ROEt + β2 SALESGRt + β3 SIZEt + β4 TANGt + β5 INSTt + β6 DYt+ ε3 3.3 where LEV, DY and INV are dependent variables in these system equations that show a possible two-way relationship among them, since they also appear at the right side of the equation as exogenous variables. ε1, ε2 and ε3 are the error terms andthey are also assumed to be correlated. ROE, SALESGR, SIZE and TANG is control variables in these sets of equation. 4. RESULTS In order to check the problem of heteroskedasticity, White’s Test for heteroskedasticity is applied. The results of the test are reported in Panel A of Table 4.3. The results of test statistics and chi- square value confirm the presence of heteroskedasticity in model. Panel B shows the results for serial correlation. The probability of test statistics confirms the presence of correlation. PANEL A: TEST FOR HETEROSKEDASTICITY Dependent Variable LEV DY Prob. INV Test Statistics F-statistic Prob. 67.17613 0.00 6.805753 0.00 12.39223 0.00 R-Square 356.0287 0.00 52.846 82.25088 0.00 0.00 Prob. PANEL B: TEST FOR CONTEMPORANEOUS CORRELATION 12.46352 0.00 3.393748 0.00 7.324963 0.00 48.57798 0.00 13.56017 0.00 28.95227 0.00 6 2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Three Stage Least Square In this table, three sets of results are reported. The first set of result being denoted by LEV where dependent variable is leverage and all exogenous and control variables are also reported. The second set of result being denoted by DY; here dependent variable is dividend yield. All explanatory variables and control variables are reported. The third set of results being denoted by INV; here investment is dependent variable and other explanatory, control and endogenous variables are also reported. The presence of dependent variables on the right side as regressor is due to two way relationship. The error terms of the relations are assumed to be correlated with each other. Results lead us to following important issues. For a cross-section of firms in Pakistan, leverage of firm is negatively related to institutional ownership and the result is highly significant. This results show that institutional owners, regardless of their type, are hesitant to invest substantial stake in the firm. The coefficient of institutional ownership is -0.01 and is highly significant at 1%. This means that if there is one unit change in institutional ownership, this would bring a negative change of 0.01 in leverage of firm. The reluctance of institutional owners to invest in highly leveraged firm may be due to their intention to avoid risk. This negative relation is the consequence of the fact that there is agency conflict among institutional owners and managers and small investors due to the bad practices of investor protection in Pakistan. The coefficient of dividend payout (-0.45) is also negative and statistically significant at 1%. This means that firm uses leverage and dividend as alternative monitoring devices. Higher the firm leverage would lower the potential dividend payout to shareholders. Looking at the control variables, it is reported that firm size has a positive role in determining firm’s level of leverage. It means big firms are more leveraged. It is consistent with the argument that as these firms have more assets as collateral and these firms are stable so these are able to arrange debt. Profitability of firm is also negatively related to firm leverage and the coefficient is significant at 95%. This result is in line with pecking order theory (Myers and Maljuf, 1984) suggesting a negative relation between the two due to reliance of firm on internally generated funds. The other control variables (TANG and SALESGR) have no significant impact in determining firms’ leverage. The coefficient of sales growth is positive Three Stage Least Square Variables Dep.Var: LEV Dep.Var: DY Dep. Var: INV Constant 1.99*** 0.0035 -0.0008*** (0.559) (0.0188) (0.0002) LEV -0.0014** (0.0008) DY -0.0024* (0.0014) INST ROE -0.01*** -0.0001 -0.000350 (0.0037) (0.0001) (0.00014) -0.0264*** 0.0003*** -0.00038*** (0.002) (0.00008) (0.000001) 7 2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. SIZE SALESGR TANG AGE DPO 0.1454*** 0.0053*** 0.000054** (0.0629) (0.0021) (0.000025) 0.002 0.00014** 0.00006*** (0.0019) (0.00006) (0.0000007) -0.0238 -0.02632* 0.0006*** (0.44) (0.0146) (0.00017) -0.0087 0.00055** 0.0000126*** (0.0082) (0.0002) (0.000003) 0.0466 0.0487 -0.465*** (0.2) adj. R square 0.0891 Chi-Sq 141.32*** 71.98*** 129.6*** Notes: *** denotes 1%, ** denote 5% and * denotes 10% level of significance. Standard errors are reported in parenthesis. LEV, DY and INV corresponds to the equations 3.4, 3.5 and 3.6 respectively. Above results are generated using dependent variables, all exogenous variables and control variables. LEV measures firm Leverage; DY measures firm Dividend Yield; INV measures firm investment; INST measures the percentage of share owned by institutional owners; ROE a measure of firm profitability; SIZE measures firm size; SALESGR represents the firm sales growth; TANG measures asset tangibility; AGE measure firm’s age in years and DPO is a measure of firm’s dividend payout. But insignificant indicating no relationship between sales growth and leverage. Age of firm is insignificant and its coefficient is negative. Looking at the results of second model, the coefficient of institutional ownership although negative but statistically insignificant thus leading us to the conclusion that in Pakistani capital market, ownership by institutions has no impact on dividend decisions of firm. These results are being supported by findings of Elston et al., (2004) who found no relationship between institutional ownership and dividend of Germen firms. Leverage of the firm adversely affects the firms’ dividend decisions and the coefficient (-.0014) is significant at 5%. The value of coefficient suggests that one unit change in leverage of firm would cause a negative .0014 unit change in dividend. This results show that in Pakistani firms, high leverage firms don’t pay dividend and it is consistent with the argument as the firms are supposed to pay interest, so they may face liquidity problem or the debt covenants may restrict them from paying dividends. The results of control variables show that profitability (Measured by ROE) has a positive role in determining the firm’s dividend decisions. Keeping other things constant, higher the profitability, higher would be the dividend yield. Moreover SIZE and SALES GROWTH (SALESGR) of firm are also positive and significant in determining the firm’s dividend. The result of SIZE is inconsistent to previous findings (Ahmed and Attiya, 2009 and Afza and Mirza 2011) who report a negative relationship of firm size with dividend. The coefficient of tangibility is negative and significant suggesting that higher the firms’ fixed assets would lower the firms’ dividend. The coefficient of AGE is significant and positive. It means that the firm’s tendency to pay dividends increases with the passage of time. 8 2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The relationship of institutional ownership (INST) and firm investment (INV) as suggested by third model is negative and the result is statistically insignificant. The negative coefficient is in accordance with the findings of Drucker, (1986); Mitroff, (1987); Scherer, (1984) and Richardson, (2002). The short term focus of institutional investors may compel the manager to reduce investment (Bushee, 1998) to avoid the mispricing caused by disappointed institutional investors’ selling. The relationship of DY and INV is significant and negative suggesting that high dividend indicate that firm is not supportive to invest in future. Dividend yield increases, investment decreases. These results are in line with the passive residual policy. These results indicate that large firms spend more in capital projects. The positive and significant relation between age and investment also confirm the same phenomenon in Pakistan. The coefficient of tangibility is significant and positive indicating that capital intensive firms are still in the process of expansion. The same phenomenon is confirmed by significant and positive relationship between sales growth and investment. The results clearly provide the evidence that high sales growth requires the firm to place more money in expansion or project/production facility. This result corresponds to the findings of Jenson et al., (1992).The presence of DY among regressor of third model is due to endogenity of variables. This study analyzes the results of simultaneous equations where industry specific dummies are incorporated into the model. Since we have 8 different industries, seven industry dummies are used for analysis. The omitted dummy variable (Engineering) becomes reference dummy and all other industry dummies are analyzed on the basis of that reference dummy. Results show that the relationship among variables remains the same in term of sign and significance. However, coefficient of INST has changed for leverage and investment. The relation becomes more pronounced. The negative impact of institutional ownership on firms’ leverage becomes more pronounced after including industry specific dummies. The magnitude of INST in second model remains same. 5. CONCLUSION This study addresses an emerging dimension of ownership; institutional ownership (as given by Pond, 1988) and its interaction with firms’ major strategic decisions, including leverage decisions, dividend decisions and investment decisions for 170 Pakistani non-financial firms across eight different sectors. Institutional ownership include firm equity owned by institutional investors like banks, insurance companies, mutual funds, pension fund, modarbah and investment trust. These institutional owners and strategic decision making by them cause endogenity problems. Three SLS technique is applied to address the issue of endogenity (Bhattacharya and Graham, 2007). Three SLS is preferred because it provides more robust estimates than 2SLS (Wooldridge 2008) To explore the relationship of institutional ownership and strategic decisions, two exogenous variables (DPO & INST), three endogenous variables (LEV, DY & INV) and five control variables (ROE, SIZE, SALESGR, TANG & AGE) are used in accordance with the previous literature (Audretsch and Elston, 2000; Najjar, 2009; Okpara & Chigozie, 2010; Afza & Mirza, 2010 and Asif et al., 2011). Moreover eight industry specific dummies are also used in 3SLS. These industries include Engineering, Chemical, Construction & Material, Paper & board, Fuel & Energy, Food Producers, Personal Goods and Miscellaneous. The purpose of using these industry dummies is to check the robustness of results. The result shows that there is two-way relationship among these strategic decisions. This relationship differs in term of magnitude of effect and sensitivity. This study results that high leverage firms pay less dividends. These results can be aligned with the findings of Jenson 9 2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. et al., (1992). The results also suggest that the firm dividend and investment has an inverse relation. Again this is supported by Peterson and Benesh, (1983) and Jenson et al., (1992). The institutional ownership has negative impact on external financing or leverage decision. As institutional ownership increases, the tendency to use more debt decreases. Profitable firms have generally less debt and this tendency is in line with pecking order theory. Profitable firms generally pay more dividends. As the distribution of dividends increases, the investment decreases. As size of firm increases, the firm uses more debt and results into more investment. However these firms also prefer to pay dividend. As firms grow older, they pay more dividends. The firms that are in high growth also take care of their shareholders. These firms not only pay more dividends but also invest more in fixed assets and their activities are generally financed from internally generated resources. The above findings remain robust when we incorporated industry dummies to capture industry-specific effects. However no significant difference among various industries is observed. This study has focused only on firm-specific factors while considering the relationship of institutional shareholding and firms’ strategic decisions. The other factors like political and economic environment have not been considered. Since this study uses internal factors only, the results might be different if external factors that may influence on strategic decisions of firms are incorporated. 6. REFERENCES Abdelsalam, O., El-Masry, A., & Elsegini, S. (2008). Board composition, ownership structure and dividend policies in an emerging market: Further evidence from CASE 50. Managerial Finance, 34(12), 953-964. Abor, J. (2007). Corporate governance and financing decisions of Ghanaian listed firms. Corporate Governance, 7(1), 83-92. Afza, T., & Mirza, H. H. (2011). Institutional shareholdings and corporate dividend policy in Pakistan. African Journal of Business Management, 5(22), 8941-8951. Agrawal, A., & Mandelker, G. N. (1992). Shark repellents and the role of institutional investors in corporate governance. Managerial and Decision Economics, 13(1), 1522. Aivazian, V. A., Ge, Y., & Qiu, J. (2005). The impact of leverage on firm investment: Canadian evidence. Journal of Corporate Finance, 11(1), 277-291. Akinlo, O. (2011). Determinants of capital structure: evidence from nigerian panel data. African Economic and Business Review, 9(1), 1-16. Al-Gharaibeh, M., Zurigat, Z., & Al-Harahsheh, K. (2013). The Effect of Ownership Structure on Dividends Policy in Jordanian Companies. Al-Najjar, B., & Taylor, P. (2008). The relationship between capital structure and ownership structure: New evidence from Jordanian panel data. Managerial Finance, 34(12), 919-933. Al-Najjar, B. (2009). Dividend behaviour and smoothing new evidence from Jordanian panel data. Studies in Economics and Finance, 26(3), 182-197. Allen, F., Bernardo, A. E., & Welch, I. (2000). A theory of dividends based on tax clienteles. The Journal of Finance, 55(6), 2499-2536. Almeida, H., & Campello, M. (2007). Financial constraints, asset tangibility, and corporate investment. Review of Financial Studies, 20(5), 1429-1460. Amidu, M., & Abor, J. (2006). Determinants of dividend payout ratios in Ghana. Journal of Risk Finance, The, 7(2), 136-145. 10 2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Asif, A., Rasool, W., & Kamal, Y. (2011). Impact of financial leverage on dividend policy: Empirical evidence from Karachi Stock Exchange-listed companies. Afr. J. Bus. Manage, 5(4), 1312-1324. Audretsch, David B.; Elston, Julie Ann (2000): Does firm size matter? Evidence on the impact of liquidity constraint on firm investment behavior in Germany, HWWA Discussion Paper, No. 113 Azzam, I. (2010). The impact of institutional ownership and dividend policy on stock returns and volatility: Evidence from egypt. International Journal of Business, 15(4), 443. Badrinath, S. G., Kale, J. R., & Ryan Jr, H. E. (1996). Characteristics of common stock holdings of insurance companies. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 49-76. Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2000). Trading is hazardous to your wealth: The common stock investment performance of individual investors. The Journal of Finance, 55(2), 773- 806. Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2008). All that glitters: The effect of attention and news on the buying behavior of individual and institutional investors. Review of Financial Studies, 21(2), 785-818. Barca, F., & Becht, M. (2001). The control of corporate Europe. Oxford University Press. Bhattacharya, P. S., & Graham, M. (2007). Institutional ownership and firm performance: evidence from Finland. School of Accounting, Economics and Finance. Bauer, P. (2004). Determinants of capital structure: empirical evidence from the Czech Republic. Czech Journal of Economics and Finance (Finance a uver), 54(1-2), 2-21. Berger, P. G., Ofek, E., & Yermack, D. L. (1997). Managerial entrenchment and capital structure decisions. The Journal of Finance, 52(4), 1411-1438. Berkovitch, E., & Kim, E. (1990). Financial Contracting and Leverage Induced Over‐and Under‐Investment Incentives. The Journal of Finance, 45(3), 765-794. Berle, A. A., & Means, G. G. C. (1932). The modern corporation and private property. Transaction Books. Boehmer, E., & Kelley, E. K. (2009). Institutional investors and the informational efficiency of prices. Review of Financial Studies, 22(9), 3563-3594 Bokpin, G. A., & Arko, A. C. (2009). Ownership structure, corporate governance and capital structure decisions of firms: Empirical evidence from Ghana. Studies in Economics and Finance, 26(4), 246-256. Brennan, M. J., & Thakor, A. V. (1990). Shareholder preferences and dividend policy. The Journal of Finance, 45(4), 993-1018. Burkart, M., Gromb, D., & Panunzi, F. (1997). Large shareholders, monitoring, and the value of the firm. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(3), 693-728. Burns, N., Kedia, S., & Lipson, M. (2010). Institutional ownership and monitoring: Evidence from financial misreporting. Journal of Corporate Finance, 16(4), 443-455. Bushee, B. J. (1998). Investors on Myopic R&D Investment Behavior. The accounting review. Bushee, B. J. (2001). Do Institutional Investors Prefer Near‐Term Earnings over Long‐Run Value?*. Contemporary Accounting Research, 18(2), 207-246. Butt, S., & Hasan, A. (2009). Impact of ownership structure and corporate governance on capital structure of Pakistani listed companies. International Journal of Business & Management, 4(2). Chichernea, D. C., Petkevich, A., & Reca, B. B. (2013). Idiosyncratic Volatility, Institutional Ownership, and Investment Horizon. European Financial Management. 11 2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Chiung-Ju Liang, Tzu-Tsang Huang, Wen-Cheng Lin, (2011) "Does ownership structure affect firm value? Intellectual capital across industries perspective", Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 12 Iss: 4, pp.552 – 570. Cho, Myeong-Hyeon (1998). Ownership structure, investment, and the corporate value: an empirical analysis. Journal of Financial Economics 47, 103-121. Chung, K. H., & Zhang, H. (2011). Corporate governance and institutional ownership. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 46(01), 247-273. Crutchley, C. E., Jensen, M. R., Jahera Jr, J. S., & Raymond, J. E. (1999). Agency problems and the simultaneity of financial decision making: The role of institutional ownership. International review of financial analysis, 8(2), 177-197. Chaganti, R., & Damanpour, F. (1991). Institutional ownership, capital structure, and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 12(7), 479-491. Chen, J. J. (2004). Determinants of capital structure of Chinese-listed companies. Journal of Business research, 57(12), 1341-1351. Chen, Z., Cheung, Y. L., Stouraitis, A., & Wong, A. W. (2005). Ownership concentration, firm performance, and dividend policy in Hong Kong. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 13(4), 431-449. Chen, X., Harford, J., & Li, K. (2007). Monitoring: Which institutions matter? Journal of Financial Economics, 86(2), 279-305. Cull, R., & Xu, L. C. (2005). Institutions, ownership, and finance: the determinants of profit reinvestment among Chinese firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 77(1), 117-146. Davis, G. F., & Stout, S. K. (1992). Organization theory and the market for corporate control: A dynamic analysis of the characteristics of large takeover targets, 1980-1990. Administrative Science Quarterly, 605-633. Deesomsak, R., Paudyal, K., & Pescetto, G. (2004). The determinants of capital structure: evidence from the Asia Pacific region. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 14(4), 387-405. Demsetz, H., & Villalonga, B. (2001). Ownership structure and corporate performance. Journal of corporate finance, 7(3), 209-233. Din, S., Javid, A., & Imran, M. (2013). External and Internal Ownership Concentration and Debt Decisions in an Emerging Market: Evidence from Pakistan. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 3(12), 1583-1597. Drucker, P.F. 1986. To end the raiding roulette game. Across the Board: 30-39. Duggal, R., & Millar, J. A. (1999). Institutional ownership and firm performance: The case of bidder returns. Journal of Corporate Finance, 5(2), 103-117. Easterbrook, F. H. (1984). Two agency-cost explanations of dividends. American economic review, 74(4), 650-659. Elyasiani, E., & Jia, J. (2010). Distribution of institutional ownership and corporate firm performance. Journal of banking & finance, 34(3), 606-620. Ezeoha, A. E. (2008). Firm size and corporate financial-leverage choice in a developing economy: evidence from Nigeria. Journal of Risk Finance, The, 9(4), 351-364. Falkenstein, E. G. (1996). Preferences for stock characteristics as revealed by mutual fund portfolio holdings. The Journal of Finance, 51(1), 111-135. Fama, E. F., & Babiak, H. (1968). Dividend policy: an empirical analysis. Journal of the American statistical Association, 63(324), 1132-116. Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Agency problems and residual claims. Journal of law and Economics, 26(2), 327-349. 12 2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. Journal of law and economics, 301-325. Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2002). Testing trade‐off and pecking order predictions about dividends and debt. Review of financial studies, 15(1), 1-33. Gaud, P., Jani, E., Hoesli, M., & Bender, A. (2005). The capital structure of Swiss companies: an empirical analysis using dynamic panel data. European Financial Management, 11(1), 51-69. Grinstein, Y., & Michaely, R. (2005). Institutional holdings and payout policy. The Journal of Finance, 60(3), 1389-1426. Grossman, S. J., & Hart, O. D. (1980). Takeover bids, the free-rider problem, and the theory of the corporation. The Bell Journal of Economics, 42-64. Gugler, K., & Yurtoglu, B. B. (2003). Corporate governance and dividend pay-out policy in Germany. European Economic Review, 47(4), 731-758. Hackbarth, D., Hennessy, C. A., & Leland, H. E. (2007). Can the trade-off theory explain debt structure?. Review of Financial Studies, 20(5), 1389-1428. Hackbarth, D., & Mauer, D. C. (2012). Optimal priority structure, capital structure, and investment. Review of Financial Studies, 25(3), 747-796. Hamdani, A., & Yafeh, Y. (2013). Institutional Investors as Minority Shareholders. Review of Finance, 17(2), 691-725. Han, K. C., Lee, S. H., & Suk, D. Y. (1999). Institutional shareholders and dividends. Journal of financial and Strategic Decisions, 12(1), 53-62. Harris, M., & Raviv, A. (1991). The theory of capital structure. the Journal of Finance, 46(1), 297-355. Hasan, A., & Butt, S. A. (2009). Impact of ownership structure and corporate governance on capital structure of Pakistani listed companies. International Journal of Business and Management, 4(2), P50. Hofler, R., Elston, J. A., & Lee, J. (2004). Dividend policy and institutional ownership: empirical evidence using a propensity score matching estimator (No. 2704). Papers on entrepreneurship, growth and public policy. Huang, G., & Song, F. M. (2006). The determinants of capital structure: evidence from China. China Economic Review, 17(1), 14-36. Jain, R. (2007). Institutional and individual investor preferences for dividends and share repurchases. Journal of Economics and Business, 59(5), 406-429. Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of financial economics, 3(4), 305-360. Jensen, M. C. (1986). Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. The American Economic Review, 76(2), 323-329. Jensen, M. C. (1988). Takeovers: Their causes and consequences. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2(1), 21-48. Jiraporn, P., Kim, J. C., Kim, Y. S., & Kitsabunnarat, P. (2012). Capital structure and corporate governance quality: Evidence from the Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS). International Review of Economics & Finance, 22(1), 208-221. Jung, K., & Kwon, S. Y. (2002). Ownership structure and earnings informativeness: Evidence from Korea. The International Journal of Accounting, 37(3), 301-325. 13 2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Karadeniz, E., Kandir, S. Y., Balcilar, M., & Onal, Y. B. (2009). Determinants of capital structure: evidence from Turkish lodging companies. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 21(5), 594-609. Koch, P. D., & Shenoy, C. (1999). The information content of dividend and capital structure policies. Financial Management, 16-35. La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1999). The quality of government. Journal of Law, Economics, and organization, 15(1), 222-279. La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (2000). Investor protection and corporate governance. Journal of financial economics, 58(1), 3-27. Lang, L., Ofek, E., & Stulz, R. (1996). Leverage, investment, and firm growth. Journal of financial Economics, 40(1), 3-29. Larcker, D. F., & Richardson, S. A. (2004). Fees paid to audit firms, accrual choices, and corporate governance. Journal of Accounting Research, 42(3), 625-658. Laverty, K. J. (1996). Economic “short-termism”: The debate, the unresolved issues, and the implications for management practice and research. Academy of Management Review, 21(3), 825-860. Lev, B. (1988). Toward a theory of equitable and efficient accounting policy. Accounting Review, 1-22. Lev, B., & Nissim, D. (2003). Institutional Ownership, Cost of Capital, and Corporate Investment. Working Paper Columbia University. Li, K., Yue, H., & Zhao, L. (2009). Ownership, institutions, and capital structure: Evidence from China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 37(3), 471-490. Lin, F. L., & Chang, T. (2011). Does debt affect firm value in Taiwan? A panel threshold regression analysis. Applied Economics, 43(1), 117-128. Liu, Q., Tian, G., & Wang, X. (2011). The effect of ownership structure on leverage decision: new evidence from Chinese listed firms. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 16(2), 254-276. Mazur, K. (2007). The determinants of capital structure choice: evidence from Polish companies. International Advances in Economic Research, 13(4), 495-514. Michaely, R., & Vincent, C. (2012). Do Institutional Investors Influence Capital Structure Decisions?. Available at SSRN 2021364. Miller, M. H., & Modigliani, F. (1961). Dividend policy, growth, and the valuation of shares. the Journal of Business, 34(4), 411-433. Mitton, T. (2004). Corporate governance and dividend policy in emerging markets. Emerging Markets Review, 5(4), 409-426. Mitroff, I. I., Mohrman, S. A., & Little, G. (1987). Business not as usual: Rethinking our individual, corporate, and industrial strategies for global competition. JosseyBass Publishers. Modigliani, F., & Miller, M. H. (1958). The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. The American economic review, 48(3), 261-297. Mookerjee, R. (1992). An empirical investigation of corporate dividend pay-out behaviour in an emerging market. Applied Financial Economics, 2(4), 243-246. Myers, S. C. (1984). The capital structure puzzle. The journal of finance, 39(3), 574-592. Ofek, E., & Richardson, M. (2002). The valuation and market rationality of internet stock prices. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 18(3), 265-287. Okpara, G. C. (2010). A diagnosis of the determinant of dividend pay-out policy in Nigeria: A factor analytical approach. American Journal of Scientific Research, 8, 5767. 14 2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Petersen, M. A., & Rajan, R. G. (1994). The benefits of lending relationships: Evidence from small business data. The Journal of Finance, 49(1), 3-37. Peterson, P. P., & Benesh, G. A. (1983). A reexamination of the empirical relationship between investment and financing decisions. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 18(04), 439-453. Porta, R., Lopez‐De‐Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (2002). Investor protection and corporate valuation. The Journal of Finance, 57(3), 1147-1170. Porter, M. E. (1992). Capital choices: Changing the way America invests in industry. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 5(2), 4-16. Rajan, R. G., & Zingales, L. (1995). What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data. The journal of Finance, 50(5), 1421-1460. Renneboog, L., & Trojanowski, G. (2011). Patterns in payout policy and payout channel choice. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(6), 1477-1490. Rozeff, M. (1982). Growth, beta and agency costs as determinants of dividend payout ratios. Journal of financial Research, 5(3), 249-259. Rubin, A., & Smith, D. R. (2009). Institutional ownership, volatility and dividends. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33(4), 627-639. Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1980). Effects of ownership and performance on executive tenure in US corporations. Academy of Management journal, 23(4), 653-664. Sayılgan, G., Karabacak, H., & Küçükkocaoğlu, G. (2006). The firm-specific determinants of corporate capital structure: Evidence from Turkish panel data. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 3(3), 125-139. Scherer, F. M. 1984. Innovation and Growth: Schumpeterian Perspectives. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Shah, A., & Hijazi, S. (2004). The determinants of capital structure of stock exchange-listed non-financial firms in Pakistan. The Pakistan Development Review, 43(4), 605618. Shah, A. Z., & Wasim, U. (2011). Impact of ownership sturcture on dividend policy of firm. Sheikh, N. A., & Wang, Z. (2012). Effects of corporate governance on capital structure: empirical evidence from Pakistan. Corporate Governance, 12(5), 629-641. Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1986). Large shareholders and corporate control. The Journal of Political Economy, 461-488. Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. The journal of finance, 52(2), 737-783. Short, H., Zhang, H., & Keasey, K. (2002). The link between dividend policy and institutional ownership. Journal of Corporate Finance, 8(2), 105-122. Sias, R. W., Starks, L. T., & Titman, S. (2006). Changes in Institutional Ownership and Stock Returns: Assessment and Methodology*. The Journal of Business, 79(6), 2869-2910. Smith, Adam. "The wealth of nations (1776)." New York: Modern Library (1937). Smith Jr, C. W., & Warner, J. B. (1979). On financial contracting: An analysis of bond covenants. Journal of financial economics, 7(2), 117-161. Smith, C. W., & Watts, R. L. (1992). The investment opportunity set and corporate financing, dividend, and compensation policies. Journal of financial Economics, 32(3), 263-292. Stulz, R., & Johnson, H. (1985). An analysis of secured debt. Journal of financial economics, 14(4), 501-521. Supanvanij, J. (2006). Capital structure: Asian firms vs. multinational firms in Asia. Journal of American Academy of Business, 10(1), 324-330. 15 2nd International Conference on Innovation Challenges In Multidisciplinary Research & Practice, December 17-18, 2014. ICMRP © 2014 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Illuminators, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Thomsen, S., Pedersen, T., & Kvist, H. K. (2006). Blockholder ownership: Effects on firm value in market and control based governance systems. Journal of Corporate Finance, 12(2), 246-269. Titman, S., & Wessels, R. (1988). The determinants of capital structure choice. The Journal of finance, 43(1), 1-19. Truong, T., & Heaney, R. (2007). Largest shareholder and dividend policy around the world. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 47(5), 667-687. Ullah, H., Fida, A., & Khan, S. (2012). The Impact of Ownership Structure on Dividend Policy Evidence from Emerging Markets KSE-100 Index Pakistan. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci, 3(9), 298-307. Wald, J. K. (1999). How firm characteristics affect capital structure: an international comparison. Journal of Financial research, 22(2), 161-187. Walsh, J. P., & Seward, J. K. (1990). On the efficiency of internal and external corporate control mechanisms. Academy of Management Review, 15(3), 421-458. Waud, R., 1966. Small sample bias due to misspecification in the ‘partial adjustment’ and ‘adapted expectations’ models. Journal of the American Statistical Association, pp. 134– 145, December. Wermers, R. (2000). Mutual fund performance: An empirical decomposition into stock‐ picking talent, style, transactions costs, and expenses. The Journal of Finance, 55(4), 1655-1703. White, H.(1980): “A Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimator and a Direct Test for Heteroskedasticity,” Econometrica, 48(4), 817–838. Zeckhauser, R. J., & Pound, J. (1990). Are large shareholders effective monitors? An investigation of share ownership and corporate performance. In Asymmetric information, corporate finance, and investment (pp. 149-180). University of Chicago Press, 1990. 16