OBSERVATIONS ON THE ORAL CAVITIES OF (WO)MAN AND BEAST

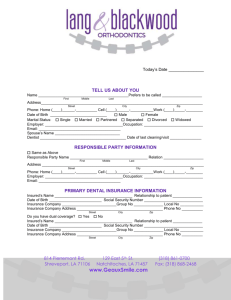

advertisement

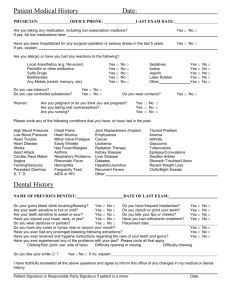

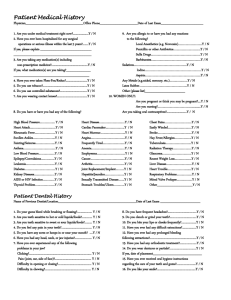

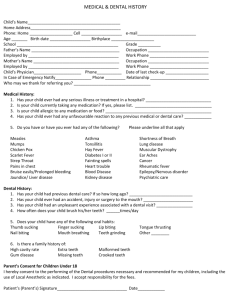

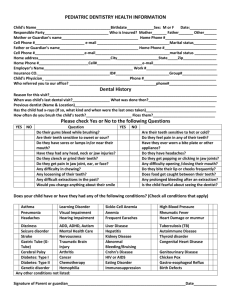

The Whole Tooth and Nothing But the Truth Eric M. Davis, DVM, FAVD, Dipl. AVDC This series on oral care and dental disease is provided by Eric M. Davis, DVM, a Diplomate of the American Veterinary Dental College. Dr. Davis is the former Director of the Dental Referral Service at the Cornell University Hospital for Animals, and is currently the Director of Animal Dental Specialists of Upstate New York, a referral clinic for veterinary dentistry and oral surgery located in Fayetteville, New York. Dr. Davis can be contacted at emdavis@adsuny.com or at 315- 445-5640. MOUTH TO MOUTH RECIPROCATION: OBSERVATIONS ON THE ORAL CAVITIES OF (WO)MAN AND BEAST Recently I was asked to speak before a group of dentists who treat humans to discuss the similarities and differences between their patients and mine. Giving the matter some thought, I realized that most humans are anthropocentric and believe that the mouths of their pets must be similar in design and function to their own. I therefore decided to share some insights into the oral, origins of the species. Primates (including lemurs, monkeys, apes, and hominids) are believed to have evolved from insectivorous tree-dwellers, and those origins and adaptations have persisted in the current, living versions of this order. Forward facing eyes, an opposable thumb, and a large big toe remain as arboreal adaptations, even though some apes and humans became terrestrial animals, losing their long tail and developing the tendency for bipedal rather than quadrupedal locomotion.1 Focusing on the oral cavity, it is clear that an omnivorous diet (fruits, vegetation, and insects) provided the basis for the rather non-specialized dentition found in primates compared to other mammalian orders such as the Carnivores and herbivorous animals such as the Artiodactyls (even toed ungulates including Bovidae) and Perissodactyls (odd-toed ungulates including Equidae) . The molar teeth of primates are low crowned, box-like teeth with rounded cusps designed for crushing and grinding. It is therefore natural for humans to think that dogs and cats must also chew their food before being able to swallow it. Such is hardly the case, and I have repeatedly reminded readers that carnivores are designed to swallow large chunks of animal tissue without requisite mastication. Whereas in monkeys and apes, the canine teeth remain as tall, impressive teeth designed for biting and/or social displays, in extant hominids, the canine teeth no longer project significantly above the height of the other teeth, even though the roots of our canine teeth are much larger than those of adjacent incisor teeth. (Who needs big canine teeth when you can carry a gun?) Since human canine teeth are small and have an incisor-like shape, there is no longer a need for a space (diastema) between the maxillary teeth to provide room for the mandibular canine teeth when the mouth is closed. The result is a rather uniform arch of front teeth that are close together (Figure 1). Primates only have four incisor teeth rather than six as found in carnivores. There is an ongoing debate as to whether the first incisor teeth (central incisors) have been lost, or if the third incisor teeth (lateral incisors) represent the missing member of the archetypal mammalian set of six incisor teeth.2 There are fewer cheek teeth as well, such that old world monkeys, apes, and hominids have 32 teeth while dogs have 42.3 That fact can be used to justify the perceived higher cost of veterinary dental care to owners. Of course since cats have only thirty teeth, veterinarians should choose this argument carefully. In contrast to primates, carnivores are designed to be able to open their mouth widely in order to effectively capture and rip apart prey. The canine teeth are large and pointed for good grasping ability. Compared to the box-like cheek teeth of omnivorous primates, carnivore cheek teeth are more pyramidal in shape (Figure 2). The carnasial teeth in particular, are designed for ripping and tearing hunks of flesh from the carcass to allow bite-sized pieces of tissue to be gulped without chewing. Because predation can sometimes involve violent struggle of the prey to escape, the oral cavity of carnivores has features that permit some degree of flexibility, thereby making it less likely for jaws or teeth to fracture. For example, the veneer of enamel which covers the dental crowns is much thinner in carnivore teeth compared to the thick layer of enamel that covers the teeth of primates4. The mandibular symphysis of carnivores is also fibrous and flexible compared to the bony union that serves to join the two mandibles of primates. Practitioners are reminded that the two mandibles of carnivores are supposed to be mobile, and they will likely remain mobile, despite even heroic efforts at “stabilization”. Another important difference between primate teeth and carnivore teeth is that among primates, teeth continue to erupt throughout life, and will erupt beyond the occlusal plane if the antagonist tooth from the opposing arch is lost.5 Among carnivores, since the upper teeth do not occlude with the lower teeth, eruption is essentially complete when the animal reaches adulthood. Thus when owners of pet dogs or cats ask if the teeth will shift in position following extraction, the answer is that they will not. Owners will also often ask if the mouth of their pet is cleaner than the mouth of a person, and that too is folklore. Since animals use their tongue as we use bathroom tissue, it hardly makes sense that a pet’s mouth should be considered clean. Animal bites often result in deep puncture wounds because the canine teeth are tall and carnivores are able to impart substantial bite forces to close their jaws. You may be relieved to learn that scientific study has confirmed that biting force is directly correlated with body size. 6 Thus the damage inflicted by the bite of a Chihuahua is usually less severe than that inflicted by a Rottweiler. Estimates for biting force in dogs range from 300-800 psi (pounds per square inch) while the biting force of humans is estimated to be 250-300 psi.7 Bites of carnivores are often contaminated with a variety of aerobic bacteria including Pasturella multocida, Staphylococcus psuedointermedius, and α-hemolytic Streptococci sp.8 Bite wounds inflicted by humans are more likely to be infected by anaerobic bacteria and must also be considered as a means of transmission for species-specific pathogens such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, and others. A recent retrospective analysis of 96 patients with human bite wounds seen at an Emergency Department between 2003 and 2005 found that the majority of patients (92%) were male, 86% of cases were associated with alcohol consumption, and the ear was the most common target (65%) of facial injuries.9 Sometimes humans can be such animals. C I2 I1 Figure 1. Side view of the occlusion of Homo sapiens. I1 I2 I3 C Figure 2. Side view of the rostral occlusion of Canis familiaris. References 1 Romer AS. Primates: Lemurs, monkeys, apes-to man. In: The Vertebrate Story 4th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1971; 309-333. 2 Swindler DR, George RM. Primate Dentition. An introduction to the teeth of non-human primates. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002: 1-11. 3 Wiggs RB, Lobprise HB. Exotic animal oral disease and dentistry. In: Wiggs RB, Lobprise HB. Veterinary Dentistry Principles & Practice. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven 1997; 538-558. 4 Crossley DA. Tooth enamel thickness in the mature dentition of domestic dogs and cats – preliminary study. J Vet Dent 1995; 12:111-113. 5 Miles AEW, Grigson C. Variations and disturbances of eruption. In: Miles AEW, Grigson C eds. Colyer’s Variations and Diseases of the Teeth of Animals Revised edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990:331-354. 6 Ellis JL. Thomason J, Kebreab E, Zubair K, France J. Cranial dimensions and forces of biting in the domestic dog. J Anat 2009; 214 (3): 362-373. 7 Wiggs RB, Lobprise HB. Oral anatomy and physiology. In: Wiggs RB, Lobprise HB Veterinary Dentistry Principles & Practice. Philadelphia, Lippincott – Raven 1997; 55-86. 8 Goldstein EJC. Bite Wounds and Infection. Clin Infec Dis 1992; 14 (3): 633-640. 9 Henry FP, Purcell EM, Eadie PA. The human bite injury: a clinical audit and discussion regarding the management of this alcohol fuelled phenomenon Emerg Med J. 2007; 24(7):455-458.