Title: Bulawayo Emergency Water Augmentation Programme (BEWAP)

advertisement

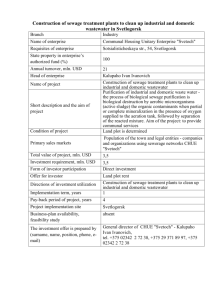

Business Case and Intervention Summary Intervention Summary Title: Bulawayo Emergency Water Augmentation Programme (BEWAP) What support will the UK provide? The UK Government through DFID will provide £3,500,000 between February and December 2013 to a consortium of three NGOs led by World Vision to increase the supply of clean water and adequate sanitation facilities to around 140,000 vulnerable residents of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe’s second city, which is suffering from severe water shortages. The rest of Bulawayo’s population (around 0.51 million more) will also benefit, but less directly, from the programme. The intervention will be delivered through: the construction and repair of boreholes; rehabilitation of water treatment and sewage plants; construction of elevated water tanks and sanitation facilities; replacement of pipes; education programmes; and a strategic appraisal and study. Why is UK support required? This programme was not envisaged under DFID’s 2011-15 Operational Plan for Zimbabwe and reflects the City of Bulawayo is experiencing unexpected and chronic water shortages with the problem exacerbated by an aging distribution system. Bulawayo is located in the driest, most drought-affected part of Zimbabwe and by the end of 2012 most of its reservoirs were dry. Following a 08 November 2012 appeal for assistance by the Mayor of Bulawayo from development partners in addressing the chronic water shortage as evidenced by the 3 day water rationing, a meeting was held in Bulawayo on 13 December 2012. The project proposal and associated funding request received from the project partner, World Vision International, captures much of their experience gained under the recently concluded AusAID funded project in Bulawayo and was prompted by this 08 November letter. It contained convincing arguments for additional support in new technical areas with an assessment of risks and benefits. Many of the WVI points were captured in the Business Case. In addition WVI were in a position to respond immediately to the urgency of the situation. The rainy season of 2011-12 saw inadequate water flows in the catchment areas feeding the reservoirs that supply water to Bulawayo’s treatment works. This resulted in water and sewage was not being efficiently and safely transferred to or from treatment works. Up to 14 December 2012 only 51% of the seasonal average had fallen, suggesting that this rainy season could be worse than last year. This is also the period of the year when urban areas are most vulnerable to cholera and other water borne diseases. On 17th January 2013, BCC’s deputy director of engineering services advised the five supply dams had received a paltry 1,5% rain-fed inflows translated to about four million cubic meters or 27 day’s supply of the city's average consumption of 145 mega litres a dayi. Revision V 12.1 (approved) 1 14 February 2013 In June 2012, the average daily consumption rate was 135 ML/day. This supply level couldn’t be sustained through to the next rainy season so in July, Bulawayo City Council (BCC) implemented 72 to 96 hours residential water rationing (water every third or fourth day). This has brought usage down to 98 ML/day. Areas that have major concentrations of industry, commercial centres or hospitals are exempt from water cuts, but schools are not and the allocation for industry and commerce is 60% lower than in June. Since the rationing program began, the percentage of processed water lost due to infrastructure breakdowns has increased to 36% and the number of pipe bursts to 4 per day. In 2008/09 Zimbabwe had the worst recorded cholera outbreak in its history: over 99,000 cases; nearly 4,300 deaths and a case fatality rate (CFR) of 4.2%. In 2011 there were 1,140 cases and 45 deaths (CFR 4.0%) and in 2012 just 23 cumulative cases and 1 death. But the countrywide breakdown of water and sewage treatment systems means water-borne disease outbreaks remain endemic and an outbreak of cholera is always a possibility. During the first 11 months of 2012 throughout Zimbabwe there were 5,805 typhoid cases, 40,745 Dysentery cases (with 22 institutional deaths) and 437,985 Diarrhoeal cases (with 269 institutional deaths). The actual numbers will be much higher taking into account non-recorded cases. The reported cases of watery diarrhoea in the BCC administered health centres (excluding the three Ministry of Health controlled City Hospitals). Cases in Jan-13 Cases in Jan-12 for comparison January -December 2012 Reported Cases in Bulawayo 13 Health Centres Under 5 years Above 5 years Total 270 284 554 232 157 389 2,778 1,977 4,675 3,402 1,725 5,275 4,030 2,465 6,495 2,937 2,534 5,471 4,646 2,896 7,542 January -December 2011 January -December 2010 January -December 2009 January -December 2008 Water based cleanliness is vital for the suppression of cholera and other diarrhoeal diseases, but is undermined where the supply is only at best 40% of requirement. With rainwater often being the transmission vector for disease, plus unsanitary conditions and a grossly inadequate supply of water, the likelihood of the return of cholera is greatly increased by water shortages. The communities in the high density suburbs (poorest areas) of Bulawayo have limited (if any) alternative safe sources of supply and so are at greatest risk of being at the centre of any outbreaks of waterborne diseases. A “Cholera Preparedness Assessment” (part of this project) is due to start in January to determine how well positioned and equipped the health services are to respond to an urban outbreak of the disease. Revision V 12.1 (approved) 2 14 February 2013 What are the expected results? By addressing infrastructure gaps and promoting hygiene education, this programme will greatly reduce the risk of the return of cholera to Bulawayo in 2013. But should cholera occur, then thanks to this intervention, the Health Services will be better able to reduce the spread of the disease and related illness and fatalities. The additional water and sanitation facilities provided and the repairs to the sewage reticulation system will reduce the risk of return of cholera beyond 2013 (WVI will work with BCC and other relevant parties to ensure operation and maintenance issues are adequately addressed). The improved school sanitation will encourage attendance especially of girls and disabled children. The specific expected results are: 1. Rapid appraisal of the Cholera preparedness response of the 17 BCC health facilities in terms of adequacy of medical stocks, equipment and training; 2. Seven new high-yield (each expected to produce around 20 m3 per day) boreholes constructed to augment current Bulawayo water supplies directly to 7 institutions; 3. Seven existing high yielding boreholes upgraded(each expected to produce around 20 m3 per day) to increase water supplies into the existing network; 4. Bulawayo’s largest water treatment works (Criterion)restored to 100% capacity thereby doubling its output to 180 Mega litres per day; 5. Eighty elevated tanks (10,000 litre capacity each)constructed in 47 Government Primary Schools, 26 Government Secondary Schools, 7 Social Welfare and community centres (including homes for the elderly, orphanages and facilities for the disabled)and connected to the water supply mains and the institutions’ own water system to ensure some supply is maintained during periods of water outage; 6. 60 to 70 kilometres of pipeline replaced to reduce bursts, leaks and losses; 7. Three outfall sewers and two sewage treatment ponds rehabilitated; 8. Improved levels of school sanitation through construction and repair of facilities to ensure all 73 schools deliver a maximum user ratio and hand washing facility ratio of 1 to 20 girls, and 1 toilet and 1 urinal to 50 boys, including a disabled toilet for both boys and girls; 9. Detailed study made of the groundwater potential in Bulawayo and adjacent aquifers currently being used or earmarked for future city supplies, including a geophysical survey to determine safe and sustainable extraction rates and any water quality constraints; and 10. Sanitation and hygiene education programmes delivered to 76,000 children in 73 schools, and a water, sanitation and water conservation message to all Bulawayo. 92% of the results will be attributable to DFID as the NGO consortium will provide £287,500 of their own funds for the programme. DFID will conduct regular monitoring of progress and the post-completion assessment will confirm whether or not the expected results were achieved. Business Case Strategic Case A. Context and need for a DFID intervention Revision V 12.1 (approved) 3 14 February 2013 The City of Bulawayo is experiencing its worst shortage of stored and supplied water since 2008. During the current 2012-13 rainy season only 51% of the seasonal average (up to 14th December 2012) had fallen and most of this will not be used to recharge the empty or near-empty reservoirs. The lack of stored water has led to 7296 hour water rationing which is designed to maintain supply on a rotational basis. But this rationing has brought with it three main related challenges. First, when pipes are not supplying water, the water pressure in the pipes drops to zero. The return of the water stresses the pipes through the sudden rise in air pressure in advance of the returning water, causing daily leaks and bursts and ultimately water loss and wastage. These surges in pressure are not normally a problem for pipes in good condition, but in Bulawayo many of the pipes have outlived their economic life and are weak and prone to bursts and should be replaced. These daily leaks put a bigger burden on the emergency maintenance crew who already have limited resources to respond. The opening on 26 November 2012 of the Bulawayo City Council (BCC) “Call Centre” has increased the opportunity for the public to report leaks, with a corresponding increase in expectations of a rapid response. This has put the spotlight on the BCC to detail and report the time taken in responding and repairing the leaks and times are reported in council meetings as a monthly performance indicator. Second, the design of the sewage system is based on all pipes receiving enough water every day to flush out debris. This has resulted in the BCC promoting the widely reported “Flush Hour” where all residents flush their toilets at the same time. However, this will only work where there are no protracted delays in supply to households and the 72-96 hour water rationing for most of Bulawayo undermines this initiative. The lack of flows in the sewage pipes has led to solidification and consequential blockage of systems, leading to overflows, bursts, and an increased risk of contamination of water supplies. Third, BCC has reported a decrease in revenue because of the reduced water sales and a reduction in the satisfaction of customers in the levels of service and their willingness to pay due to rationing, visible losses due to leaks and bursts, and the failure of the sewage systems in residential areas. Less revenue means fewer resources to invest in repairs and upgrades. Overall therefore there is a significant and increased risk to residents’ health through reduction in water supply and the possibility of ruptured sewage lines. Previous water shortages in 1992 and 2008 led to increased cases of diarrhoea, typhoid, and cholera. Without enough safe water, residents will use less water for sanitary cleansing (prioritising instead the washing and preparation of food), and/or look to unsafe sources to meet their needs which increases the risk of contracting diarrhoea and other fast spreading enteric and waterborne diseases. Vulnerable groups such as the elderly, disabled, sick and very young are at most risk as they are likely to be less able to access clean water away from their homes. School children are particularly likely to spread disease during play and other interactions if they have inadequate sanitation facilities and water supply both at home and at school. Schools in Bulawayo were not designed for the current number of students enrolled and as a result the sanitation facilities are insufficient. Many Revision V 12.1 (approved) 4 14 February 2013 schools operate double shifts of pupils so putting a greater strain on the infrastructure and increasing the opportunity for disease transmission. Schools are not exempt from the current water cuts and so may go without water supplies for 72 to 96 hours. Urban schools do not generally have easy access to alternative water sources and many have no facilities to store water when it is available in order to maintain hygienic conditions at the schools when water is cut. There is therefore a great need to provide permanent storage facilities at all 73 schools to help them cope with the current and future water outages. Six social welfare institutions (including homes for the elderly, orphanages and facilities for the disabled) and community centres are in the same situation. A further challenge is where Bulawayo’s water should come from in the long term. Groundwater is considered the viable alternative to surface treated supplies. Whereas there is potential for future extraction from underground, the recent capacity of the aquifer to produce water given the low rainfall of recent years is uncertain and so a better understanding of the sustainability and limits to extractions rates is urgently required to help find a longer-term solution to the city’s water shortages. Zimbabwe is a fragile and conflict-affected state that has experienced significant violence along regional and ethnic lines in recent decades. Bulawayo and the Ndebele people have been particularly affected. There is no evidence so far of the current water shortages turning tensions among communities into conflict or violence. But if the problems are left unaddressed or there is a major outbreak of fatal waterborne diseases then that could change. The programme is therefore likely to help reduce that likelihood and is certainly not expected to make things worse. The Bulawayo City Council and the Ministry of Water Resources Development and Management have been trying to address the deteriorating water supply situation, but with very limited resources. In recent months senior figures in the Bulawayo and central government have appealed to donors including the UK to provide urgently support to address the long- and short-term water and sanitation needs of Bulawayo, but none have responded with concrete offers. Although this programme was not envisaged in DFID’s 2011-15 Operational Plan for Zimbabwe, water and sanitation is a key pillar of DFID’s work in Zimbabwe (mainly in rural areas) and elsewhere in the world. DFID has become increasingly active in the water sector in Zimbabwe in the past 12 months and is well placed to respond. Our full-time infrastructure adviser meets key government, donor and non-governmental players in the sector on a weekly basis and has made several trips to Bulawayo in recent months. B. Impact and Outcome that we expect to achieve This programme will contribute to the achievement of the MDGs (see table below). At impact level this programme will contribute to a reduction in morbidity and mortality due to WASH related diseases such as cholera and diarrhoea in high risk areas of Bulawayo. The programme also aims to significantly improve the lives of poor women and girls through, for example, a reduction in water borne disease cases reported in under-5s and an increase in water production and available for consumption by 90,000 m3 per day. Millennium Development Goal Revision V 12.1 (approved) Project Contribution 5 Comment 14 February 2013 1. Eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, minor Assists in freeing time for more productive activities. 2. Achieving universal primary education, important 3. Promoting gender equality and empowering women, important 4. Reducing child mortality rates, important 5. Improving maternal health, important 6. Combating HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases, important 7. Ensuring environmental sustainability, and important Attendance of children at school–especially girls expected to increase due to improved water and sanitation facilities. Attendance of girls expected to increase due to improved sanitation facilities Improved water quantities and quality will reduce incident of diarrheal disease. Hygiene in health centers will improve as a result of increased water. Reduction in stagnant pooling of sewage will prevent mosquitoes and transmission of diarrheal diseases. Environmental pollution from sewage spills controlled. Correct extraction rates for sustainability of groundwater resources established. 8. Developing a global partnership for development Not applicable As an outcome, the programme will enable communities to continue to have access to water and sanitation facilities, practice improved health and hygiene behaviour and benefit from improved collection and storage of safe drinking water, hand washing and use of improved sanitation facilities. The programme focuses on the needs of the poor and vulnerable (e.g. people with disabilities, the aged and chronically ill) in the high density, low-income urban communities in Bulawayo with the lowest WASH access who are at highest risk from water borne diseases. But it will also campaign for behaviour change in high-income, low density areas where large amounts of water are used for gardens, swimming pools, car-washing etc. Any reduction in demand in these areas will increase supplies in the poorer areas, even where such supplies are coming from privately owned boreholes often in the belief that groundwater is unlimited and free. Ward Households Pop Primary Sch Sec Sch Children Enrolled Boys Revision V 12.1 (approved) 6 Girls Total enrolled year 2011 14 February 2013 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Totals 3,867 7,240 8,018 7,380 5,303 3,479 4,802 5,830 7,187 7,605 4,697 6,789 5,130 5,200 3,089 4,170 4,195 5,928 5,275 4,547 7,010 4,798 4,909 6,011 6,038 5,134 7,450 11,342 4,669 167,092 12,258 27,824 29,920 25,112 18,757 13,404 17,910 24,260 27,836 29,436 19,249 26,674 19,763 20,588 12,876 16,923 17,267 22,941 20,842 19,029 28,473 19,447 19,500 23,847 24,987 21,196 31,259 45,348 18,749 655,675 3 5 6 3 3 2 1 3 2 2 1 4 1 1 1 1 2 1 4 - 1 1 1 47 1 1 26 4 1 2 2 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2,165 2,280 1,378 910 3,335 1,542 208 3,058 3,381 1,430 1,056 3,425 529 1,548 266 651 1,295 1,835 1,082 3,223 664 248 695 807 1,079 38,090 2,615 2,304 1,449 884 2,987 1,788 222 3,214 3,722 1,602 1,190 3,652 561 1,681 247 824 1,443 1,968 1,194 3,328 698 248 762 925 1,137 40,645 4,780 4,584 2,827 1,794 6,322 3,330 430 6,272 7,103 3,032 2,246 7,077 1,090 3,229 513 1,475 2,738 3,803 2,276 6,551 1,362 496 1,457 1,732 2,216 78,735 Specifically it is anticipated that the following results will be achieved: 1. Rapid appraisal of the Cholera preparedness response of the 17 BCC health facilities in terms of adequacy of medical stocks, equipment and training; 2. Seven new high yield boreholes constructed to augment current Bulawayo water supplies directly to seven health facilities; 3. Seven existing high yielding boreholes upgraded to increase water supplies into the existing network; 4. Bulawayo’s largest water treatment works (Criterion) restored to 100% capacity thereby doubling its output to 180 Ml/day; 5. 80 elevated tanks (10,000 litre capacity each) constructed in 47 Government Primary Schools, 26 Government Secondary Schools, 7 Social Welfare and community centres (including homes for the elderly, orphanages and facilities for the disabled)and connected to the water supply mains and the institutions’ own water system to ensure some supply is maintained during periods of water outage. 80,000 people (including 76,000 children are expected to benefit); 6. 60 to 70 kilometres of pipeline replaced to reduce bursts, leaks and losses; 7. Three outfall sewers and two sewage treatment ponds rehabilitated; 8. Improved levels of sanitation through construction of facilities at 60 out of 73 Revision V 12.1 (approved) 7 14 February 2013 schools to deliver a maximum user ratio and hand washing facility ratio of 1 to 20 girls and 1 toilet and 1 urinal to 50 boys, including a disabled toilet for both boys and girls; 9. Detailed study made of the groundwater potential in Bulawayo and adjacent aquifers currently being used or earmarked for future city supplies, including a geophysical survey to determine safe and sustainable extraction rates and any water quality constraints; and 10. Sanitation and hygiene education programmes delivered to 76,000 children from 73 schools, and a wider water, sanitation and water conservation message to the whole of Bulawayo. Appraisal Case A. What are the feasible options that address the need set out in the Strategic case? Option 1. The 7 December 2012 proposal from a consortium of NGOs comprising World Vision International (lead), MedAir (Switzerland) and Dabane Trust (Bulawayo) is financed through an Accountable Grant. The work will be broken down into the 10 areas set out above and the work shared out in the consortium according to their experience and expertise (details below). It would take around a minimum of five months to run a competition and contract a supplier. So open competitive tendering is dismissed given the urgency of the situation. The consortium partners are well established with a proven history with DFID or other funding mechanisms in Zimbabwe. Subsequent payments after the initial advance will be linked to progress against delivery of results. World Vision International World Vision International has over four years’ experience of WASH programming in Bulawayo and strong and active partnerships with BCC and other stakeholders, enabling good coordination with partners and rapid implementation of planned interventions. WVI is the chair of the BOWSER Steering Committee that will become the Bulawayo Water Steering Committee. Through the BOWSER project WVI has been working closely with National ministries, BCC, Bulawayo Sewage Task Force (BSTF), the Dabane trust, twinning relationship with Ethekwini Municipality’s WASH department (Durban) and private sector providers to reduce waterborne diseases for 450,000 people through improved sewerage and water supply systems as well as an improved customer care and financial sustainability of BCC in the provision of such services. In addition WVI has a strong WASH team including engineers and technical advisors on the ground who are implementing similar projects and large grants. Under this project WVI will be doing the major infrastructure activities, including rehabilitating Criterion water works, replacing burst and aging pipes, and rehabilitating outfall sewers and ponds. WVI also has a central Programme Partnership Agreement with DFID Headquarters. Medair Medair has been implementing a wide range of both urban and rural WASH projects Revision V 12.1 (approved) 8 14 February 2013 in Zimbabwe since 2010. In the town of Marondera, Medair rehabilitated the water treatment plant providing 120,000 residents with clean water. In Gokwe District, Medair rehabilitated the town’s water supply system, drilled boreholes and rehabilitated wells in order to increase water supplies for 25,065 residents of Gokwe town. In rural Gokwe, MedAir focused on rehabilitation and digging of new wells, installing Rainwater Harvesting Systems at schools and conducting Participatory Health and Hygiene Education (PHHE) thereby reducing the risk of water borne disease for 32,580 beneficiaries. Medair is currently implementing a rural WASH project in the districts of Mangwe and Bulilima in Matebeleland South (adjacent to Bulawayo) by rehabilitating boreholes, providing rainwater harvesting systems at 30 schools and clinics and conducting PHHE in the schools in order to reduce the risk of waterborne disease for some 126,000 beneficiaries. Under this project Medair will be undertaking the installation of the water storage tanks at the strategic institutions as well us conducting the PHHE within the schools. Dabane Trust Dabane has considerable capacity and experience with urban based WASH initiatives. As a local NGO with a locally based Board of Management Dabane has the capacity to engage in emergency initiatives, rapidly and positively. Dabane has very well established links with local authorities including the Bulawayo Mayor, Town Clerk, Bulawayo Governor, Ministry representatives, Bulawayo senior engineers and implementing technicians. Dabane’s strength in effective operation and message delivery lies in an ability to connect to and work with the local Ward Councillors and Residents Associations. Dabane also has a strong practical and technical team with a determined approach to delivering effective, quick and meaningful change. For example, Dabane’s quick response to introduce high pressure jetting equipment to significantly improve and increase the clearing of some 20,000 metres of the city’s sewage reticulation system earned the praise and respect of residents and City Hall. Dabane was a founder member of the Bulawayo Sewage Task Force (BSTF), an amalgam of Bulawayo City Council, NGO’s and private industry which led to the BOWSER programme. It has a place on the Water and Sewage Steering Committee and continues to interact and co-ordinate with all main parties presently involved. Under this project Dabane Trust will be conducting the groundwater survey as well as completing school sanitation activities, including disabled students. Option 2. Commit funding through GIZ/AusAID Programme Since June 2012 the German and Australian Governments (through their development agencies GIZ and AusAID) have been supporting the local authorities in six towns and cities in Zimbabwe including Bulawayo to improve service delivery and revenue collection. In Bulawayo the programme aims to: re-establish water and sanitation services; and increase revenue collection for water, sewage and refuse charges to 60% of that billed from the average 33%. The focus under the first component is to use the ground water supply from the Nyamadlovu and Epping Forest well fields more efficiently, but the improvements in pumping equipment and storage will take more than a year to complete. Option 3. Commit Funding through the “Zim-Fund” A consortium of bilateral partners has contributed $120 million into the Zimbabwe Multi-Donor Trust Fund (Zim-Fund) managed by the African Development Bank. DFID with £20 million is the largest contributor. Zim-Fund is working to improve access to Revision V 12.1 (approved) 9 14 February 2013 water in six urban centres in Zimbabwe, including Bulawayo. The Zim-Fund is not however structured to provide a rapid response to challenges such as the current water-shortages facing Bulawayo, something which the AfDB itself recognises. Option 4. Engage a Private Contractor to provide these services. This option would require the engagement of such an organisation based on detailed Terms of Reference and the procurement of their services to follow competitive tender processes. Experience in the Multi Donor Trust fund (Zim-Fund) has shown that a competitive tendering process would take many months to complete and would not see delivery on the ground until late 2013 at the earliest. Option 5. Do nothing For reasons set out above, Options 2 to 4 will not deliver improved water and sanitation services in 2013. The national and local authorities are trying to improve the supply of water to the city (for example through the Mtshabezi pipeline), but lack sufficient resources to carry out other projects (the Insiza Dam duplication pipeline has an estimated cost of $37 million). So the bottom line is that if DFID did not support this programme, the WASH vulnerabilities of many of the poorer residents of Bulawayo would remain unmet, leaving an ever increasing risk of disease for them. Evidence underpinning the theory of change Zimbabwe has already experienced the disastrous consequences of failing to invest in improved access to safe water and basic sanitation for the most vulnerable populations. In 2008/9, lack of access to safe water and improved sanitation facilities combined with poor hygienic practices contributed to a cholera outbreak that affected all ten provinces of the country with more than 99,000 cumulative cases and 4,300 deaths being recordedii. Diarrhoea remains one of the top ten diseases affecting children under-5 in Zimbabwe, causing around 4,000 deaths every year iii. Low water and sanitation reliability and coverage, cholera proneness and high HIV infected and affected populations are some of the key rationales accepted globally for targeting of WASH interventions. As noted above, donors have contributed $120 million into the Zimbabwe Multi-donor Trust Fund (Zim-Fund) to help address some of the funding shortages crippling the restoration of urban water supplies. The projects being financed are large scale rehabilitation projects with the purpose of restoring services closer to former service levels. But the results are not expected to be seen before the end of 2013. Diseases associated with poor water and sanitation has considerable public health significance. At a global level, improving water, sanitation and hygiene has the potential to prevent at least 9.1% of the disease burden (in disability-adjusted life years or DALYs, a weighted measure of deaths and disability), or 6.3% of all deathsiv. In 2003, it was estimated that 54 million DALYs or 4% of the global DALYs and 1.73 million deaths per year were attributable to unsafe water supply and sanitation, including lack of hygienev. According to the WHO Global Burden of Disease 2004, 4.9% of Zimbabwe’s total burden of disease as measured by DALYS was WASH relatedvi. Evidence of economic benefits arising from water and sanitation improvements Research studies and anecdotal evidence have firmly established that poor access to safe water, sanitation and hygiene is a cause for substantial economic losses. A Revision V 12.1 (approved) 10 14 February 2013 recent studyviiestimates the economic loss of inadequate sanitation in Bangladesh to be US $4.2 billion a year, equivalent to 6.3% of the country’s GDP in 2007. The study estimates that the economic losses result from: a) premature death and morbidity) water treatment costs and the time spent fetching water; and c) user preference impact which considered the extra time needed for open defecation, and the time lost by girls and women due to absence from school and work respectively. The study also finds that measurable gains could be achieved by WASH interventions by reducing premature death and related morbidity, eliminating domestic water related costs and reducing absentee time at school and work places. The study found out that 61% of Bangladesh’s WASH related economic losses could be prevented. The potential savings are equivalent to US$ 2.56 billion. Another studyviii that estimates the economic costs and benefits of a range of selected interventions to improve water and sanitation services argues that the potential productivity and income effects of improved access to water, sanitation and hygiene constitute a significant argument to leverage further resource allocations to water and sanitation. The study identified economic benefits arising from water and sanitation improvements under the following categories: health sector, patients, consumers and agricultural and industrial sectors. Health sector benefits arise, depending on who is paying, from less expenditure on treatment of diarrhoea diseases in the form of drugs and use of hospital systems. The study also identified time savings related to water collection or accessing sanitary facilities. Bulawayo was founded in the 1840’s, and is the second largest city in Zimbabwe. It developed as an important regional industrial and transport hub. It is the provincial capital of Matabeleland and the centre of Zimbabwe’s largest minority ethnic group the Ndebele. Some commentators argue that Bulawayo has been marginalized in the past due to its political affiliations, including in recent times its strong support for the MDC parties who have been the main opposition to President Mugabe’s ZANU-PF since 2000. Bulawayo has always struggled to supply adequate water to its citizens. Much of this is due to climatic factors: Bulawayo has an average annual rainfall of 590 mm, and is in one of the hottest and driest parts of the region. Given that the combined yield of existing dams is 73.6 Mega litres/day (Ml/d) and the demand before the current water shedding was 135 Ml/day it is clear that Bulawayo needs to increase its water supply. The table below sets out the main options: Sources Surface Ground Water Development Options Given to BCC Meeting December 2012 • Mtshabezi Dam • Insiza Dam • Gwayi-Shangani Dam Detailed study of the groundwater potential in Bulawayo and adjacent aquifers Revision V 12.1 (approved) 11 Comment Large capital works projects and outside this project. Ministry of Water Resources and Management leading. BEWAP to carry out study. Geologically Bulawayo is on an extensive granitic outcrop underlying a shallow layer of immature soil. Groundwater is found in fracture zones with aquifers largely restricted to river basins. Analysis of drilling 14 February 2013 Loss reduction Recycled Effluent • Improve Nyamadlovu Wellfield • Epping Forest Wellfield • Sandstone Creek • Sawmills Aquifer • Gwayi Siding • Nata River • Intundhla Siding Bulawayo is more water efficient than any other city in Zimbabwe so not a lot of room for improvement • Master Plan proposes indirect recycling of treated effluent through Khami Dam. • Only 10% to 20% of sewage generated in catchment flows to the sewage treatment works, balance spills from failed trunk sewers into streams flowing to Khami Dam Until spillage of raw sewage to Khami Dam is resolved, Master Plan proposal for recycling cannot be considered. Revision V 12.1 (approved) 12 logs and existing records will be used for borehole assessment and to provide data on variations in groundwater levels with mapping and yield assessment in the high density suburbs. The use of Geoeye satellite data a 3D view of an aquifer will be produced for immediate use and for longterm data interpretation. ArcGIS based 3D aquifer water potential and lithological model and AutoCAD civil 3D based aquifer model produced. The model will be operated and updated by ZINWA. GIZ / AusAID. GIZ / AusAID. No development planned. BEWAP will replace 60 to 70 km of mains with a predicted 8% reduction in the water being lost. BEWAP will rehabilitate 3 trunk sewers (Mpopoma, Turnall and Mahatshula Bridge) ensuring that the sewage goes to the treatment works (being rehabilitated by AusAID/GIZ) and not untreated into the Khami dam 14 February 2013 B. Assessing the strength of the evidence base for each feasible option The table rates the quality of evidence for each option as; Strong, Medium or Limited. Option Evidence rating 1 BEWAP Strong 2 GIZ/AUSAID Strong 3 Zim-Fund Strong 4 Private Sector Strong 5 Do Nothing Strong The evidence rating above reflects the confidence held in our assessment of the capacity of each organisation to respond with the urgency that the project requires. All the options other than “do-nothing” will have start up delays. Option 1 being the consortium of three NGO’s currently active in Bulawayo gives the greatest confidence for the early positioning of assets to execute the project. The “do-nothing” Option has compelling evidence that the water and sanitation situation will not improve and very likely deteriorate without this investment. The ten proposed activities have been carefully chosen to supplement the programmes of other partners active in Bulawayo and would have a much greater short-term impact than channelling money through the Options 2-4. What is the likely impact (positive and negative) on climate change and environment for each feasible option? Environmental Appraisal & Climate Change Considerations The infrastructure activities under the programme will not significantly contribute to climate change or environmental degradation, or lead to increased vulnerability of communities. Drilling activities may see minor contamination of surface water from drilled materials or drilling lubricants. In addition, open holes pose a danger to people, poultry and cattle in the area. Therefore best practices must be applied to rehabilitate and restore the drilling sites. Noise and dust during construction work is inevitable, but it will be temporary and easily controllable by restricting working hours and ensuring all material excavated from the boreholes is correctly disposed of. Overall any minor degradation linked for example to drilling will be managed by an Environmental Management Plan. Any negative environmental impact will be more than off-set by improvements to the environment resulting from repaired sewerage system, with fewer numbers of spills of untreated sewage into the residential community or water courses. In addition the work to restore failed sewage transmission and treatment facilities will help reduce the risk of contamination of groundwater by sewage, and increase the amount of sewage reaching the sewage treatment works and the volume of sewage effluent available for recycling. Replacement sewers will be designed and sized to ensure adequate flows of water to ensure ‘self-cleaning’ and reduce the likelihood of blockages. Groundwater is the only realistic safe water supply option for meeting the dispersed demand that characterises low density rural villages in the adjacent rural districts of Bulawayo. Therefore access to groundwater by rural communities outside the city should arguably take priority over extraction to supply the needs of large urban centres like Bulawayo. The groundwater study to be carried out under this programme Revision V 12.1 (approved) 13 14 February 2013 will help to establish what volume of water can sustainably be extracted. This should help ensure that all future large-scale ground water extractions for Bulawayo are sustainable, including in terms of their consequential impact on the rural areas around the city. Looking ahead, while the use of water for irrigation has declined significantly in the past decade or so around Bulawayo (linked often to land reforms), this pattern could reverse and the balancing of the needs of agricultural and urban areas would require careful management by the Zimbabwe National Water Authority (ZINWA). The proposed construction/rehabilitation of 14 boreholes should have negligible impact on groundwater levels under Bulawayo. This may well not be the case with the proposed expansion of the Nyamadlovu wellfield and the development of Epping Forest wellfield under the AusAID/GIZ programme which have the potential to significantly lower the water table in the surroundings areas if the extraction rates are not matched with recovery in-flows (with potential knock-on effects to the areas where those in-flows come from). The proposed development plans and extraction rates from the two major well fields are based on data that may be outdated or based on outdated assumptions. Understanding the hydrogeology is the key to identifying how the water point will behave under stress and also the long-term sustainability of groundwater resources under the impact of drought and climate change, which once again underlines the value of the groundwater study under this new programme. No quality problems are expected from the water to be extracted from the new and rehabilitated boreholes. But all of the boreholes will be tested and any appropriate action taken. The boreholes will only be drilled where there is sufficient groundwater to pump to storage tanks at institutions where the water can be chlorinated and gravitated into the reticulation system. Protecting the groundwater under Bulawayo and the surrounds requires resource management. Although groundwater is generally well protected, the proposed increased development of local wellfields could have impacts on quality issues. Extraction of water in areas that encourages the percolation of water contaminated by industrial or mining wastes as well as avoiding problems with using water with unsafe levels of naturally occurring chemicals can be identified through the groundwater study. As this is a fixed urban environment where the potential for future urban growth is concentrated in the peripheral areas, there is limited scope for the outcomes to be enhanced by improved management of natural resources and tackling climate change. However all wetlands, important for flood attenuation and aquifer recharge (as well as habitats for natural flora and fauna) will be mapped to feed into the groundwater study. The Participatory Health and Hygiene Education component should improve community health and environmental hygiene. For example increase social awareness of the need to dispose of garbage responsibly and correctly should have positive effects on the environment. Messages will be conveyed through road shows, fun days, creation of Health Clubs in schools, door–to-door campaigns, text messaging, billboards and other material. Health and hygiene fun days will be conducted at the time of the construction of school sanitation facilities at schools with parents invited to raise awareness on health and hygiene practices. Environmental health technicians and community volunteers will be involved in door to door health and hygiene campaigns that seek to promote and enhance safe hygiene and health Revision V 12.1 (approved) 14 14 February 2013 practices at household level. Overall, there is limited scope for the project to help tackle climate change, build resilience or reduce vulnerability to climate change or related shocks. But as noted above it will help to improve the environment and its management. As set out in a previous section, Options 2-4 are not realistic given the urgency of the situation, therefore the summary table below only covers Option 1. Option 1 Climate change and Climate change and environment environment risks and opportunities, Category (A, B, C, D) impacts, Category (A, B, C, D) Low Risk Medium Opportunity C. What are the costs and benefits of each feasible option? Detailed cost benefit analysis was only undertaken for Option 1. Options 2-4 were rejected as they would not be able to respond to the urgency of the situation in Bulawayo. The programme considered in Option 2 has a longer time horizon with valid commercial intentions to ensure sustainability but will be unable to respond quickly enough. Option 3, ZIMFUND, has proved to be slower than expected in terms of delivery on the ground while Option 4, engaging a private contractor, would also be a lengthy process. The contributions are as follows for Option 1 :Source DFID Contribution to WVI M&E (retained) Contingencies (retained) Total WVI Contribution Total support Amounts £3,420,766 + £50,000 + £29,234 £3,500,000 £287,500 £3,787,500 Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) have important social and economic benefits, with implications for environmental cleanliness, health, poverty reduction and (gender) equity. Access to safe water and improved sanitation will reduce the burden of diseases arising from WASH related causes, especially by providing barriers to transmission of diarrhoeal disease from the environment to the human body. This will result in not only improved health status for the poor and vulnerable but also lead to economic benefits realised through a number of channels such as: savings on health expenditure; lower incidence of illness from water borne diseases which include water treatment; time savings from reduced walking distances to fetch water; and improved education outcomes particularly for girls when their attendance in school is improved because the burden of fetching water will have been reduced. 1. Costs Table 1 below summarises the breakdown of annual costs to be incurred against Revision V 12.1 (approved) 15 14 February 2013 programme activities including overheads. The total cost of the programme is GBP 3,787,500 (USD 6,060,000), with GBP 3,500,000 (USD $5,600,000) provided by DFID and the balance of GBP 287,500 ($460,000) from the NGO’s. Table 1: Project costs (US$) Revised DFID 23 Jan 2013 USD (equivalent) GBP XR 1.6 Feb-13 £2,000,000 USD 3,200,000 Apr-13 May-13 £710,383 USD 1,136,613 Jul-13 Aug-13 £710,383 USD 1,136,613 Disburse Date Total USD to WVI (equivalent) Total UKP to WVI from DFID £3,420,766 Retained Funds by DFID M&E Contingencies 0.8% Total DFID £50,000 £29,234 £3,500,000 USD 5,600,000 £287,500 USD 460,000 £3,787,500 USD 6,060,000 WVI Contribution Total Value of Project USD 5,473,225 Table 2: Project costs (US$) COSTS 1. Rehabilitation of Criterion water treatment works to increase supply from 90 Ml/day to 180 Ml/day 2. Construction of 80 elevated tanks in institutions 3. Construction of 7 new high yield boreholes to augment current Bulawayo water supplies 4. Upgrading of 7 existing high yielding boreholes to augment current Bulawayo water supplies. PARTNER TOTAL World Vision International Medair USD 814,903 Dabane Trust Dabane Trust 5. Replace 60-70 km of pipeline to reduce the World number of bursts (and unseen minor) leaks where Vision pipe bursts are frequent and losses significant. International 6. Repair and maintain sewage infrastructure World through the rehabilitation of three outfall sewers Vision and two sewage treatment ponds. International Dabane 7. Construct sanitation facilities at schools Revision V 12.1 (approved) 16 USD 578,400 USD 127,453 USD 100,399 USD 1,384,507 USD 425,246 USD 14 February 2013 8. Carry out a detailed study of the groundwater potential in Bulawayo and adjacent aquifers 9. Introduce sanitation and hygiene education programmes to 76,000 children from 73 schools. 10. Rapid assessment Preparedness. of BCC’s Cholera Trust 678,792 Dabane Trust USD 73,618 Medair, Dabane Trust World Vision International USD 477,375 USD 334,507 4,995,200 Subtotal Overheads 478,025 Total cost 5,473,225 Overhead costs payable to World Vision International will amount to USD 478 k or 9.5% of funds contributed by DFID to WVI over the duration of the programme. 2. Benefits We identify four types of economic benefits: 1) lives and productive time saved, which would otherwise have been lost due to death and illness respectively as measured by Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs); 2) health expenditure savings comprising of hospital treatment costs; 3) patient costs savings comprising of transport costs to access a health facility; 4) time savings arising from reduced time taken to collect clean water. The valuation of health benefits (DALYs) in this appraisal was restricted to the burden of diarrhoeal diseases among children under 5’s closely following the work of Haller et al. ixand Hutton et alx. The above identified benefits are certainly not the only benefits of the programme. Due to computational limitations and the inherent difficulty to monetise some of the benefits, not all benefits are accounted for in this appraisal. Some of the benefits that this appraisal did not quantify include: The reduction in the diarrhoeal burden of diseases on the adult population. In 2008/9 poor access to water and sanitation resulted in a cholera and diarrhoeal disease outbreak that killed 4 300 people. Reduction in water related diseases such as vector borne diseases which are not accounted for under diarrhoeal diseases. Sanitation time savings arising from having a sanitation facility in the school could not be accounted for because of lack of evidence to demonstrate the amount of time spend looking for vegetation cover to openly defecate or queuing to use the limited resources in the school. Table 2 summarises the assumptions for the valuation of benefits and the data sources for parameters values used in the calculation. A detailed explanation of the assumptions and parameter values is given in Appendix 1. Revision V 12.1 (approved) 17 14 February 2013 Table 2: Parameter values for computation of benefits Benefit Value of lossof-life avoided/ Time lost due illness Direct treatment expenditures saved Patient costs Time savings Salvage value Variable Diarrhoea Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) Gross National Income (GNI) per capita % of DALYs saved Unit costs per treatment Hospitalisation costs(5 days) Data values 16 /1000 capita/Year Data Sources WHO Zimbabwe Country profile (2009) US$ 630 Own office calculation (2011) 80% in population MOHCW, WHO, reached UNICEF 5.5 US$ (Swaziland & Jamison et al. 2006 Malawi) Hutton et al. 2004 110 US$ (SubSaharan Africa ) Number of Cases by proportion Demographic & Health cases saved of under-fives Survey 2010-111 reached (13%) Case visits 30% of cases seek Assumption Hutton et out patient care al. 2004 Hospitalisation 8.2% of cases WHO data Transport costs US$ 1 per trip Assumption based on per visit minimum public transport rates % of patients 50% Hutton et al. 2004 using transport Water collection 0.5 hours Assumptions guided time saved per by MIMs 2009, households per Nemarunde 2003 day (borehole) Time savings US$ 525 Calculation based on valued at GoZ Poverty Datum opportunity Line for family of five costs of time at minimum wage for general agriculture As a conservative measure, the salvage value estimated at zero for both boreholes and squat holes Further assumptions That around 20% of the Bulawayo population or 140,000 people would be reached with a full package of benefits covering water, sanitation and hygiene education. This assumes 10,000 people benefit from each borehole constructed or rehabilitated and 1 Demographic & Health Survey page 133 table 10.7 states incident ate in under 5 yo is 13.2% Revision V 12.1 (approved) 18 14 February 2013 45,000 people from each of the improvements to the sewage reticulation system. In the central scenario, that the estimated average life span of a borehole is 20 years and hence benefits will subsist for 20 years after funding has stopped, which gives an appraisal horizon of 21 years including the one year of programme implementation. In the valuation of time savings, it was assumed that average household income is US$ 525 (GoZ Poverty Datum line for family of 5) which is shared between two equally productive members of the household. Undiscounted Benefits Using the above assumptions, it was calculated that this programme will avert 16 DALYs per 1000 people per year. This was multiplied by the number of DALYs by per capita GNI to get the discounted monetary value of DALYs. Health expenditure is calculated by multiplying the number of diarrhoeal cases by the proportion of cases that seek treatment and then by the average cost of treatment. The same applies to hospital fees. Patient costs avoided are calculated by the number of cases that seek treatment by the cost of a round trip to and from hospital. And finally the time savings benefit is calculated by multiplying the total time saved due to having an improved water source by the opportunity cost of time which is equivalent to household income earnings obtained from the LIME (Longitudinal approaches to Impact assessment, Monitoring and Evaluation) survey of May 2011 for lack of a better proxy for the opportunity cost of women’s labour. Table 3 below outlines the computed undiscounted incremental benefits from the programme. Table 3: Undiscounted benefits (US$) Benefit item 2014 Total (20 years) 1,792 Number of DALYs Saved Value of DALYs saved ($) 1,128,960 Health Expenditure saved($) 30,030 Patient costs saved($) 2,730 Time savings ($) 3,675,000 Total benefits 4,836,720 35,840 22,579,200 600,600 54,600 73,500,000 96,734,400 3. Balance of Benefits and Costs Table 4 below presents the balance of discounted benefits and cost for the base case at a discount rate of 10% in line with DFID Zimbabwe’s discount rate estimates. Table 4: Balance of Cost and benefits Economic Indicator Base case Total discounted benefits 41,177,724 Total discounted costs 5,393,050 Net Present Value 35,784,674 Benefit Cost Ratio 7.64 Internal Rate of Return 89.7 The project has a Net Present Value (NPV) of US$ 35.8 million and a benefit-cost ratio (BCR) of 7.64 which means that for every dollar invested in the BEWAP, a return of at least US$ 7.64 is expected. The project has an Internal Rate of Return (IRR) of Revision V 12.1 (approved) 19 14 February 2013 89.7% which means that the returns realised from the BEWAP outweigh the opportunity cost of capital by more than 7 times. Sensitivity Analysis In order to address the uncertainty surrounding some of the variables used, a sensitivity analysis was conducted and Table 5 presents the scenarios used. Table 5: Sensitivity analysis scenarios Parameter Base case Lifespan of benefits Minimum costs Projects benefits will last twenty (20) years after programme funding has stopped maintenance Zero maintenance costs, throughout the project but the responsibility for O&M is found in the Log Frame DALY valuation DALYs saved valued at GDP per capita of US$ 630. Efficacy of DALY savings Efficacy of DALY savings pegged at 80% All the sensitivity test scenarios insert a degree of caution to the central/base scenario which has high positive returns. The results of the sensitivity tests are shown in table 6 below. Table 6: sensitivity analysis results Scenario NPV ($) Base 35.8 m S1 – 10 year benefit flow 24.3 m S2 – maintenance costs 34.3 S3 – Hh income ($250) 17.9 IRR (%) 89.7 89.5 89.7 53.8 BCR 7.6 5.5 5.9 3.6 As can be seen from Table 6, all the less optimistic scenarios of the BEWAP have positive NPVs. Even with the lifespan of project benefits reduced by 10 years in the 1 st scenario, the project has a positive NPV of approximately US$ 24.3 million and a BCR of 5.5. While maintenance costs were assumed to be zero in the base case, when maintenance costs of 10% per annum from year 10-20 were assumed in the second sensitivity test, the programme still registered a positive NPV of US$ 34.3 million and BCR of 5.9. We also assumed in scenario three that the low end opportunity cost of labour used to value DALYS is equal to the Household Income of about US$ 250, which represents the minimum earnings of a poor household in Zimbabwe. The results show that the programme is more sensitive to the value attached to the opportunity cost of labour. However, even at this lower end opportunity cost of labour, the project still has positive returns with a BCR of 3.6 which means that every dollar invested earns a return of US$ 3.60 (NPV of $17.9 m). Revision V 12.1 (approved) 20 14 February 2013 D. What measures can be used to assess Value for Money for the intervention? Component Number Item Unit Cost Per Item USD 1. Increase Criterion WTW production 90 Ml/day to 180 Ml/day 90,000 m3 per day 0 0.02 267 Not applicable 6 Not applicable 814,903 2. Construct 80 x 10,000 lt tanks. 80 tanks 7,230 Not applicable 189 7,230 7 Not applicable 578,400 3. Construct 7 new high yield boreholes 7 Borehole 18,208 To be advised 42 18,208 13 Not applicable 127,453 4. Upgrade 7 existing boreholes 7 Borehole 14,343 To be advised 33 14,343 10 Not applicable 100,399 5. Replace 70 km pipe reduce losses by 10 % 70,000 m 20 Not applicable 453 Not applicable 10 $27,000 per day (Rate $1 per m3) 6. a Repair and maintain three outfall sewers 3 repairs 255,14 8 To be advised 139 85,049 3 Not applicable To be advised 139 85,049 2 Not applicable Cost per item per year USD Cost USD Per Daly averted Cost USD per institution Cost per person improved WASH behaviour USD Cost USD economies in water usage Total Cost USD 1,384,507 425,246 6. b Repair and maintain sewage infrastructure rehabilitation of two sewage treatment ponds. 2 repairs 170,09 8 7. Construct sanitation schools 60 sanitation upgrade 9,299 To be advised 222 9,299 9 Not applicable 678,792 8. Study groundwater potential in Bulawayo and adjacent aquifers 1 Study 73,618 Not applicable Not applicable Not applicable Not applicable Not applicable 73,618 9. Hygiene education programmes 76,000 children from 73 schools. 76,000 Child 6 Not applicable 156 6,539 6 Not applicable 477,375 10. Rapid assessment of BCC’s Cholera Preparedness 1 study 334,50 7 Not applicable Not applicable Not applicable Not applicable Not applicable 334,507 Revision V 12.1 (approved) 21 14 February 2013 E. Summary Value for Money Statement for the preferred option The preferred option for this project is Option 1 principally because it allows a rapid response to the critical situation in Bulawayo while still offering strong Value for Money. Option 1 also allows DFID to engage the consortium under an Accountable Grant that limits how the funds will be spent to various categories but gives freedom for funds to be moved around within those categories. Detailed cost benefit analyses for options 2-4 were not undertaken. Option 5 “Do-nothing” is the counter argument to Option 1 giving reasons for not implementing Option 1. The appraisal demonstrated that Option 1 offers good value for money. A benefit cost ratio (BCR) of 5 to 6 and an internal rate of return (IRR) of 54% to 89%. This level of return is consistent with returns of similar interventions in Zimbabwe and elsewhere. Even when some parameter values used in the calculation of benefits were lowered in the sensitivity test the BCRs remained above unit, implying that benefits outweigh costs even under less optimistic scenarios. Commercial Case Direct procurement A. Clearly state the procurement/commercial requirements for intervention The funding is being provided in response to a proposal made by World Vision International (WVI) and its partners MedAir and Dabane Trust, all of whom are notfor-profit organisations. The Appraisal Case gives details of their work and experience in Zimbabwe and the proposed division of labour between them. This programme will not involve any direct procurement by DFID. All procurement will be indirect and through WVI. WVI will act as the managing agent for this programme. There will be an Accountable Grant signed with WVI. There will be the standard requirements for joint reporting and oversight to minimise transaction overheads to all parties. We anticipate disbursing funds in advance and on a quarterly basis. They will be subject to the appropriate statements and reports as set out in the Accountable Grant. Disbursement schedules will be agreed within the Accountable Grant negotiation process and contingent upon satisfactory performance. None of the funds will be earmarked. B. How does the intervention design use competition to drive commercial advantage for DFID? The provision of goods will be from the local markets and procured by tender based on WVI’s procurement rules. As part of the procurement process WVI will assess the quality of goods against price and will select based on the lifetime cost for the goods Revision V 12.1 (approved) 22 14 February 2013 being installed. Labour engaged for installation will be directly supervised by WVI or its associates and will be contracted on a daily basis or by contract labour supply organisations. World Vision UK’s position on “Value for Money, Principles, management practices and plans for measurement” can be viewed on http://www.worldvision.org.uk/whatwe-do/impact/ C. How do we expect the market place will respond to this opportunity? The market will respond to increase demand for goods and services. Through the tendering process, goods may be imported but due to the urgency to improve the supply of services it is anticipated that goods will be obtained locally or regionally. The may be an increase in daily rates for the costs of labour but this is likely to be insignificant due to the high unemployment rates in Bulawayo. D. What are the key cost elements that affect overall price? How is value added and how will we measure and improve this? Most of the goods to be procured are locally available, supplied from local sources or imported (most likely) from neighbouring South Africa. There is less control over costs of imported goods and exchange rate fluctuations may have an influence but prices will be fixed in USD at time of ordering. Wherever practicable, labour-intensive methods of construction will be employed maximising the retention of funds in the local community. E. What is the intended Procurement Process to support contract award? There will be direct negotiation with World Vision International for these services. F. How will contract & supplier performance be managed through the life of the intervention? Bulawayo City Council will create a Project Steering Committee to meet monthly to discuss progress and provide support. DFID will be represented on that committee as will local community representatives. Simple Monthly reports will be produced by WVI listing progress against targets and disbursements against targets. Quarterly reports will be produced giving detailed of expenditures to allow replenishment of funds. Indirect procurement A. Why is the proposed funding mechanism/form of arrangement the right one for this intervention, with this development partner? Due to the urgency to progress the project, there is no alternative other than to directly negotiate with World Vision International. They are a leading player in the WASH sector in Bulawayo and this is project they can take on with little delay in recruitment or delays due to establishment. Revision V 12.1 (approved) 23 14 February 2013 We have not received any other proposals of this kind from CSOs and going out to tender is likely to delay work starting by at least six months, a delay which is not acceptable given the urgency and the severity of the situation facing the most vulnerable people in Bulawayo. WVI and its partners enjoy effective and proven relationships with Bulawayo City Council that will be key to successful implementation and they also know the city and the locations where much of the improvements are to be focused. B. Value for money through procurement WVI will be expected before undertaking any procurement activity to familiarise and ensure all procurement conforms to the code of conduct of the UK Chartered Institute of Purchasing and Supply (CIPS) code. The key issues to be addressed by WVI are below but apply equally to DFID staff and are:a. Declaration of interest. Any personal interest of any WVI staff (including other implementing partners in association) which may affect or be seen by others to affect WVI’s impartiality in any matter relevant to any WVI procurement should be declared to DFID. Personal interest expressly includes any DFID or WVI friends or family that are thinking of bidding for work. In this situation, DFID will decide on an appropriate response and will inform WVI in writing of the action to be taken. b. Confidentiality and accuracy of information. The confidentiality of information received in the course of this project should be respected and should never be used for personal gain. Information given in the course of duty should be honest and clear. The details of one supplier’s quotation should never be released to another supplier. c. Competition. The nature and length of contracts with suppliers can vary according to circumstances. These should always be constructed to ensure speedy deliverables and maximum benefits. Arrangements which might in the long term prevent the effective operation of fair competition should be avoided. d. Business gifts. - Business gifts, other than items of very small intrinsic value such as business diaries or calendars, should not be accepted. e. Hospitality. WVI staff should not allow themselves to be influenced or be perceived by others to have been influenced in making a business decision as a consequence of accepting hospitality. The frequency and scale of hospitality accepted should be managed openly and with care and should not be greater than WVI is able to reciprocate. Financial Case A. What are the costs, how are they profiled and how will you ensure accurate forecasting? The expected costs are set out below. Subsequent sections provide more details about profiling and forecasting. COSTS USD 1. Rehabilitation of Criterion water treatment works Revision V 12.1 (approved) 24 814,903 14 February 2013 2. Construction of 80 elevated tanks in institutions 578,400 3. Construction of 7 new high yield boreholes 127,453 4. Upgrading of 7 existing high yielding boreholes 100,399 5. Replace pipeline to reduce the number of bursts (and unseen minor) leaks etc 6. Repair/maintain sewage infrastructure through the rehabilitation of three outfall sewers and two sewage treatment ponds. 1,384,507 425,246 678,792 7. Construct sanitation facilities at schools 73,618 8. Carry out a detailed study of the groundwater potential in Bulawayo and adjacent aquifers 9. Introduce sanitation and hygiene education programmes to 76,000 children from 73 schools. 10. Rapid assessment of BCC’s Cholera Preparedness. Subtotal USD Overheads 9.5% 477,375 334,507 4,995,200 478,025 Total Cost USD 5,473,225 GBP 3,420,766 B. How will it be funded: capital/programme/admin? Programme Resource. C. How will funds be paid out? It is anticipated funds will be disbursed as follows: Disburse Date GBP Feb-13 Apr-13 May-13 Jul-13 Aug-13 USD £2,000,000 USD 3,200,000 £710,383 USD 1,136,613 £710,383 USD 1,136,613 Total USD to WVI (equivalent) Total UKP to WVI £3,420,766 Retained Funds by DFID M&E Contingencies 5% Total DFID £50,000 £29,234 £3,500,000 USD 5,600,000 £287,500 USD 460,000 WVI Contribution Revision V 12.1 (approved) USD 5,473,225 25 14 February 2013 Total Value of Project £3,787,500 D. What is the assessment of financial risk and fraud? USD 6,060,000 The risks are considered to be small, with the funds only being channelled through WVI with approved financial management and audit systems. WVI has a Programme Partnership Agreement with DFID and has worked successfully with DFID Zimbabwe in other sectors. WVI Zimbabwe has recently been awarded a contract under DFID’s Girls Education Challenge Fund whose selection process included an assessment of the organisation’s financial management controls. Expenditure will be carefully monitored to ensure it is being used for the defined purposes, in line with acceptable accounting procedures, representing value for money. E. How will expenditure be monitored, reported, and accounted for? This contribution is not considered sensitive, novel or contentious and will be funded from programme resources that have been budgeted for in DFID Zimbabwe’s Operational Plan. Expenditure will be carefully monitored to ensure it is being used for the defined purposes, in line with acceptable accounting procedures, representing value for money. DFID Zimbabwe’s Programme Manager will ensure forecasting, monitoring and accounting of expenditure using DFID financial management systems. The Accountable Grant will govern disbursement and be agreed beforehand with WVI. The Programme Manager will conduct quarterly meetings with WVI partners to review project progress, monitor expenditure trends against forecasts and assess overall compliance. Monthly coordination meetings will be held in Bulawayo with the main relevant parties and field visits carried out to cross-check against financial reports. WVI will supply audited statements of account. Financial records will be audited in accordance with the globally established procedures and financials rules and regulations. Any capital assets procured will be treated in accordance with DFID procedures. Management Case A. What are the Management Arrangements for implementing the intervention? For the reasons outlined earlier we recommend WVI to manage this programme, working with Medair and Dabane Trust. B. What are the risks and how these will be managed? Risk Revision V 12.1 (approved) Probability Impact 26 Mitigation 14 February 2013 Political and economic Low situation worsens to civil conflict or collapse of BCC services to sectors. High Change of political leadership in BCC following elections in 2013. Low Medium WVI is unable to Low effectively work with all partners, including Government, as well as having full site access to implement and monitor the programme. WVI’s internal Low procurement systems are unable to effectively expedite and manage large scale expenditures at the start. Change of leadership Low within WVI or partners. Medium Overall costs of Low procurement of goods and services escalate beyond reasonable levels. Medium Significant tensions arise Low between the collaborating partners with WVI or BCC. Medium Revision V 12.1 (approved) 27 Because the programme is Bulawayo based it is subject to all the problems associated with urban political tensions. The programme has little political overtones and therefore should be immune to targeted violence or interference. The project is not seen to have a political context but the political reality is that any change of leadership (even from within the same political party) will view any on-going projects with a degree of caution. Early meetings with any change of political elite will be necessary. Bulawayo City Council is a key partner but once the launch has occurred support from BCC is only required at the low level technical level as part of the implementation. Medium WVI to ensure procurement capacity available in early phase of the project. Medium Ensure any proposed changes to staff have an adequate handover and the replacements staff is as wellequipped and motivated as the staff departing. As a principle local procurement is encouraged to develop the local economy wherever possible but WVI to manage the risk of compromising implementation quantity or quality. Agreements to be signed (MoU’s) between implementing partners to emphasize the need to work together, commit to a transparent process free of 14 February 2013 politicization. C. What conditions apply (for financial aid only)? Does not apply D. How will progress and results be monitored, measured and evaluated? The project budget includes £50,000 to cover the cost of field visits and reporting. £29,234 has been set aside for contingencies as approved by DFID. Monitoring and evaluation will take place quarterly to ensure that evidence is gathered regarding the impact of the various interventions included in this business case. This will serve to potentially assist to direct future WASH interventions as some of the benefits accrued in urban settings are poorly argued due to lack of supporting evidence. The monitoring and evaluation will also serve to increase understanding of the challenges of engaging in WASH urban activities. DFID will work with WVI to develop a communication and dissemination strategy for the key monitoring and evaluation findings. We will work with WVI to build in appropriate beneficiary feedback into our monitoring and evaluation plans. This will complement the other aspects of the monitoring and evaluation plan by providing grassroots information on the impact of the programme on the lives of the poor. Standard DFID programme management practises for monitoring and evaluation will be implemented and agreed in the Accountable Grant. There is requirement before the disbursing of the 2 nd and 3rd payments that the outputs for milestones in the Logframe are substantially achieved. Logframe Quest No of logframe for this intervention: 3845406 Bulawayo dams record 1. 5% inflowsi http://bulawayo24.com/index-id-news-sc-local-byo-25088.html ii Ministry of Health and Child Welfare (MOHCW) Epidemiology Bulletin, 2008/9 iii Multiple Indicator Monitoring Survey (MIMS), 2009, a household survey undertaken by the Zimbabwe Statistical Agency (ZimStats) in conjunction with UNICEF. iv Pruss-Ustun A, et al, Safer water, better health: costs, benefits and sustainability of interventions to protect and promote health. World Health Organization, Geneva, 2008. v Hutton G et al, ‘'Economic and health effects of increasing coverage of low cost household drinking-water supply and sanitation interventions to countries off-track to meet MDG target 10. WHO 2007. vi The global burden of disease: 2004 update, WHO publication 2008. “The Economic Impacts of Inadequate Sanitation in Bangladesh” viii “Evaluation of the Non-Health Costs and Benefits of Water and sanitation Improvements at a Global Level” WHO 2004, by Hutton G and Haller L ixHaller L, Hutton, G & Bartam J. 2007. Estimating the costs and benefits of water and sanitation improvements at global level. Journal of water and health 05. 4:467-480 xHutton G& Haller L. 2004. Evaluation of the Costs and Benefits of Water and Sanitation Improvements at the Global Level. WHO, Geneva vii Revision V 12.1 (approved) 28 14 February 2013