Getting to Know Shakespeare*

advertisement

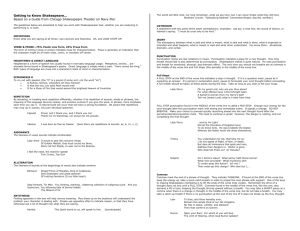

Getting to Know Shakespeare… Based on a Guide from Chicago Shakespeare Theater on Navy Pier The guidelines below are presented to help you work with Shakespearean text, whether you are analyzing it, performing it, or both. DEFINTIONS Know what you are saying at all times—use Lexicons and footnotes. Oh, and LOOK STUFF UP! VERSE & PROSE—75% Poetic Line Form, 25% Prose Form The form of writing (verse or prose) indicates clues for characterization. Prose is generally an indication that the character might be of lower class, comic, or mentally off-center. HEIGHTENED & DIRECT LANGUAGE Heightened is a form of speech not usually found in everyday language usage. Metaphors, similes... are elevated forms found in Shakespeare’s poetry. Direct language is simply what is said: “Here comes the King.” Both types of language are clues into a character’s state of mind or characterization. ECPHONESIS O To cry out with passion (the “O” is a sound of some sort, not the word “oh”) O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo? O that this too, too solid flesh would melt O for a Muse of Fire that would ascend the brightest Heaven of Invention REPETITION By stressing, or treating each repetition differently, whether it be repetition of sounds, words or phrases, the meaning of the language become clearer, and emotion evolves if you give the word, or phrase, more emphasis each time you say it. A natural build will occur that will have a strong foundation. Be aware that repetitions may crop up in scenes, not just individual speeches. Capulet Proud, and I thank you, and I thank you not. Thank me no thankings, nor proud me not prouds… Cassius I was born as free as Caesar. OXYMORON A statement with two parts which seem contradictory; examples: sad joy, a wise fool, the sound of silence, or Hamlet’s saying: “I must be cruel only to be kind.” IRONY The discrepancy between what is said and what is meant, what is said and what is done, what is expected or intended and what happens, what is meant or said and what other understand. You know them: situational, dramatic, and verbal. PUNCTUATION Punctuation marks are like notations in music. Punctuation indicates a place for a new thought. How long breath should last is also determined by punctuation. Shakespeare makes it quite natural. He uses punctuation and breath for emotional, physical, and dramatic effect. The only time you should not breathe are at commas in the middle of the verse line and Full Stops (like periods) in the middle of the verse line. Full Stops A FULL STOP at the END of the verse line indicates a stop in thought. If it is a question mark, pause as if expecting an answer. If a period or exclamation point, pause to formulate your next thought before proceeding. A full breath should be taken at these points during the stop. Take as long as you wish to full your lungs. Lady Percy Oh my good Lord, why are you thus alone? For what offense have I this fortnight been A banish’d woman from my Harry’s bed? Tell me (sweet Lord) what is it take from thee FULL STOP punctuation found in the MIDDLE of the verse line is called a MID STOP. Change your energy for the next thought after this punctuation mark with strong and immediate intent. It signals a change. DO NOT BREATHE. Make your choice to proceed quickly launching ahead into the next thought found after the period/exclamation/question mark. The need to continue is great! However, the danger is rushing, and not completing the first thought. Lady Percy …and by his Light Did all the Chevalrie of England move To do brave Acts. He was (indeed) the Glasse Wherein the Noble Youth did dress themselves. Troilus You understand me not, that tells me so: I do not speak of flight, of fear, of death, But dare all imminence that gods and men, Address their dangers in. Hector is gone: Who shall tell Priam so? Or Hecuba? Dolphin Am I Rome’s slave? What penny hath Rome borne? What men provided? What munitions sent To under-prop this Action? Is’t not I That under-go this charge? Who else but I, … [here there are repetitions of sounds: az, ē, rrr, c, z] ASSONANCE The likeness of vowel sounds indicate emotionality Lady Anne O would to god the inclusive Verge Of Golden Mettall, that must round my Brow, Were red hot Steele, to sear me to the Braines. I feel the need, the need for speed! (Top Gun) ALLITERATION The likeness of sounds at the beginnings of words also indicate emotion Berowyn Dread Prince of Placates, King of Codpieces, Sole Emperator and great general! Of trotting Parrators (O my little heart). ANTITHESIS Finding opposites in the text will help convey meaning. Play these up so the audience will understand the problem your character is dealing with. People use opposites often to indicate reason, or that they have otherwise put a lot of thought into what they are saying. Hamlet This Spirit dumb to us, will speak to him. [dumb/speak] Commas Commas mark the end of a phrase of thought. They indicate THINKING. If found at the END of the verse line keep the energy up, take a quick catch-breath in order to propel the next phrase with support. One of the keys to making Shakespeare interesting is to lift the ends of the verse lines vocally. Remember the drive of a thought does not end until a FULL STOP. Commas found in the middle of the verse line, like this one, also demand a lift in tone, keeping the thought driving upward without a breath. You may take a SHORT pause at a comma when there is a change in thought in the middle of the verse line, but do not take a breath. You may take a catch-up breath if there is no punctuation at the end of the line IF it does not break up the thru thought. Lear To thee, and thine heredity ever, Remain this ample third of our fair Kingdom, No less in space, validity, and pleasure Then that confer’d on Goneril. Rumor Open your Ears! For which of you will stop The vent of Hearing, when loud Rumor speaks? Colons & Semi-Colons Both of these punctuations mark the end of a phrase of thought, but do not mark the conclusion of the main idea. Only a full stop tells the actor to end. Colons and semi-colons tell the actor that a new phrase of thought is coming and he or she will need a shift in energy to make that thought clear and separate from the previous thought. Take a quick breath at this point and you will accomplish the change. Think of it as gear shifting from thought to thought, propelling the ideas forward, with supporting breath, toward their destination at the end of the complete sentence. The breath you take should be a short, “thinking” breath. Hamlet To be, or not to be, that is the Question: Whether ‘tis Nobler in the mind to Suffer… Duke …: therefore I pre’thee Supply me with the habit, and instruct me How I may formally in person bear Like a true Friar: More reasons for this action At our more leisure, shall I render you; Only, this on: Lord Angelo is precise, Stands at guard with envy: scarce confesses That his blood flows: or that his appetite Is more to bread then stone: hence shall we see If power change purpose: … Parenthetical Phrases The text shows the character having a thought, changing that thought to a new thought, then returning to the old thought. The parenthetical thought is a diversion or digression. They “color” a sentence. It is most interesting to the audience if you Change the pitch or speed of your voice when introducing the new thought found within parenthetical punctuation. Parenthetical phrases also qualify an expression or are used as an after-thought. Parenthetical phrases can be indicated by ( ), or commas. Sometimes they are not punctuated at all. For the actor a parenthetical phrase means change: vocal change in speech, pitch and attitude. For clarity take a catch-up breath before or after the punctuation. Always look for the thru-thought to make sense of parenthetical phrasing. Don Armado I do affect the very ground (which is base) where she shoe (which is baser) Guided by her foot (which is basest) doth tread. Horatio At least the whisper goes so: Our last King, Whose image even but not appear’d to us, Was (as you know) by Fortinbras of Norway, (Thereto prick’d on by a most emulated Pride) Dar’d to the Combate. In which, our Valiant Hamlet, (For so this side of our known world esteem’s him) Did slay this Fortinbras: who by a Seal’d Compact, Well ratified by Law, and Heraldry, Did forfeit (with his life) all those his Lands Which he stood seiz’d on, to the Conqueror: … Hyphens Hyphens (—) in Shakespeare indicate that the character is changing who s/he is speaking to. The changes for an actor are similar to those needed with parenthetical statements. Always look to understand the new thought in connection to the thru-thought or thought that comes before the dash. SHARED LINES Serve up the last line of your speech to your scene partner and that actor then picks up the energy by jumping on his or her first line. Understanding shared lines involves simple knowledge of iambic pentameter. Ten syllables to a verse line is the norm. Isabella Angelo IAMBIC PENTAMETER Shakespeare wrote, as his basis for rhythm, ten syllables to the verse line. This is the natural rhythm of the English language. The “iamb” foot is a two-syllable unit of rhythm where the second syllable gets the emphasis. Examples of words that are iambic appear below. Consider how you would say them. Where does your voice naturally rise in pitch, strengthen, or get louder? That’s the syllable that is emphasized. alone prepared below respect away condemn around within forget alas surprise content When you put 5 iambic feet together (that’s pairs of syllables), that’s “pentameter” (5 feet). Guess how many total syllables make up a line of 5 iambic feet? That’s right, 10, which brings us back to the point we started with: Shakespeare wrote, as his basis for rhythm, ten syllables to the verse line. [Note: In the example text below, look for shared lines and short lines.) Angelo Your Brother is a forfeit of the Law, And you but waste your words. Isabella Alas, alas: Why all the souls that were, were forfeit once And he that might the vantage best have took If he, which is the top of Judgment, should But judge you, as you are? Oh, think on that, And mercy then will breathe within your lips Like man new made. Angelo Be you content (fair Maid) It is the Law, not I condemn your brother, Were he my kinsman, brother or my son, It should be thus with him; he must die tomorrow. Isabella Tomorrow? Oh, that’s sodaine, Spare him, spare him: He’s not prepared for death; even for our kitchen We kill the fowl of season: shall we serve heaven With less respect then we do minister To our gross selves? Good, good, my Lord, bethink you; There’s many have committed it. MONOSYLLABIC WORDS, PHRASES, OR LINES Monosyllabic words and phrases usually tell the actor to slow down thoughts because the ideas you are using, or thoughts you are working through, are important. Hamlet To be, or not to be, that is the Question: Constance I trust I may not trust thee for thy word. SMALL WORDS (and, yet, but, or, therefore) Always indicate a change of thought. They are words of logic. RHYMES Allow the character to enjoy his or her own cleverness, usually indicating the end of a speech. It is very easy to get into a downward inflection with rhymes. Avoid that. Katherine An mercy then will breathe within your lips Like Man new made. Be you content (fair Maid)… Then vale your stomachs, for it is no boot, And place your hands below your husband’s foot: In token of which duty, if he please, My hand is ready, may it do him ease. DOUBLE ENTENDRE Shakespeare used sexual puns to amuse and titillate his audiences. SHORT LINES (incomplete lines of verse) A pause before or after a short line can indicate time for though or a physical stage direction. Spare him, spare him. Here comes the King. Parolles Man setting down before you, will undermine you, and blow you up.