Theorizing about Congress

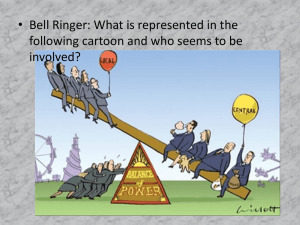

advertisement

Political Science 206b/847b - Theorizing about Congress Spring 2013 To meet in ISPS Room B012 On Tuesdays at 1:30-3:20 David R. Mayhew, office hours on Tuesdays at 3:30–5:30 and by appointment, at 87 Trumbull Street, Room 230. (Come in through the entrance at 77 Prospect Street, but note that this entrance locks up at 5:00; if you get there after that, phone me and I will let you in.) Telephone: 432-5237 Email: david.mayhew@yale.edu Website: http://pantheon.yale.edu/~dmayhew/ The course topic: There is a long tradition of theorizing about the U.S. Congress—that is, the devising of analytic frames of one kind or another. This seminar takes up a succession of those frames. It has a flavor of science but also of history and historiography: The science needs to be historicized. The ideas of various authors will be examined and also bounced against current circumstances on Capitol Hill. A guide to much of the course may be found in D.R. Mayhew, “Theorizing about Congress,” chapter 38 in Eric Schickler & Frances E. Lee (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the American Congress (2011), an online book where this chapter appears near the end under “Reflections.” Also, the chapter will be posted on the class server. The course mechanics: This is a reading and discussion seminar. It will not accommodate senior essays or other long research papers. There a heavy reading requirement each week. Each undergraduate will write a series of five analytic comment papers, three to five pages in length. Each of these will address a required weekly reading assignment chosen by the student to dwell on. Graduate students will write four of these papers plus, by the close of the reading period, an extended bibliographic essay on a suitable topic (which might be cross-national comparative). Students are expected to be ready to discuss the required readings in class. No midterm or final exams. Required books used extensively will be available at the Yale Bookstore. Required books used in any part will be stocked on library reserve. Most of the short required readings should be available online chiefly through ORBIS; some will be posted on the class server. Yale Writing Center: Its URL is http://writing.yalecollege.yale.edu/advice-students. Here may be found a guide for responsible source use. January 15 – Organization meeting Background: Nelson W. Polsby & Eric Schickler, “Landmarks in the Study of Congress since 1945,” Annual Review of Political Science 5 (2002), 333-67 Bruce I. Oppenheimer, “Behavioral Approaches to the Study of Congress,” chapter 2 in Eric Schickler & Frances E. Lee, The Oxford Handbook of the American Congress (Oxford UP, 2011) 1 Ira Katznelson, “Historical Approaches to the Study of Congress: Toward a Congressional Vantage on American Political Development,” chapter 6 in Schickler & Lee, Oxford Handbook January 22 – Separation of powers Required: Selections from Alexander Hamilton, John Jay & James Madison, The Federalist (1787-88). This classic is available in copious quantities everywhere—libraries, bookstores, Amazon, etc. The Yale Bookstore will stock new or used editions, and any edition will do. Several editions are available online through ORBIS. The reading specifications below should apply to any edition. They add up to some 35-40 pages. --Number 10 – just the five-paragraph section two-thirds of the way through that starts with “The two great points….” This has the “refine and enlarge” idea. --Number 35 – roughly the last half, starting with the paragraph that begins “The idea of an actual representation….” What kinds of folks are optimal representatives? --Number 37 – a long paragraph in the middle that begins “Among the difficulties….” The need for a certain stability. --Number 47 – the first eight paragraphs. Why have separation of powers? --Number 48 – the first six paragraphs. Checks and balances. --Number 51 – entire. Ambition checking ambition. --Number 55 – entire. Size of the House. --Number 57 – roughly the first half, through the paragraph that begins “Such will be the relation…” On House members as representatives. --Number 58 – entire. House versus Senate. --Number 62 – entire. The Senate. --Number 63 – the first nine paragraphs through the one that begins “It adds no small weight to….” The Senate, continued. William H. Riker, “The Senate and American Federalism,” American Political Science Review 49:2 (June 1955), 452-69. In practice, how did the Senate evolve? Suggested: Jeremy Waldron, “Separation of Powers or Division of Power?” NYU working paper 2012, downloadable as PDF. A sharp analysis of the question: Why bother to have three elected institutions? Bernard Manin, “Checks, Balances and Boundaries: The Separation of Powers in the Constitutional Debate of 1787,” chapter 2 in Biancamaria Fontana (ed.), The Invention of the Modern Republic (Cambridge UP, 1994). A sharp analysis of the Madison/Hamilton logic of checks and balances. Samuel P. Huntington, “The Founding Fathers and the Division of Powers,” in Arthur Maass (ed.), Area and Power (Free Press, 1959). The differing justifications of Adams, Jefferson, and Hamilton for dividing power. 2 Bernard Manin, The Principles of Representative Government (Cambridge UP, 1997), chapter 3 (“The Principle of Distinction”). The elitist implication of having government by “consent.” Charles O. Jones, The Presidency in a Separated System (Brookings, 2005). In practice, how have the three elected branches interacted in recent times in making policy? January 29 – Dispersed influence and deliberation Required: Woodrow Wilson, Congressional Government (1885). Any edition is OK. Several are available online through ORBIS. Suggested: Leon D. Epstein, “What Ever Happened to the British Party Model?” American Political Science Review 74:1 (March 1980), 9-22. The model that animated Wilson. Samuel P. Huntington, “Congressional Responses to the Twentieth Century,” chapter in David B. Truman, Congress and America’s Future (Prentice-Hall, 1973). A sprightly essay that takes up the Federalist and Wilson questions forty years ago. Jeffery A. Jenkins & Charles Stewart III, Fighting for the Speakership: The House and the Rise of Party Government (Princeton UP, 2013). New work on the development of House parties and committees in the 19th century. February 5: Spatial dissonance Required: James MacGregor Burns, The Deadlock of Democracy: Four-Party Politics in America (Prentice-Hall, 1963). Not an online book. Yale has only a couple of copies. Yale Bookstore will stock. Amazon lists at least 25 used copies at under $10. Suggested: Richard Bolling, House Out of Order (E.P. Dutton, 1965). Characterizes the House back then as the conservative outlier among the three institutions. Samuel Kernell, “Is the Senate More Liberal than the House?” Journal of Politics 35 (1973), 33266. Answer: Yes, generally speaking, back then. David R. Mayhew, Partisan Balance (Princeton UP, 2011), chapter 3. Why back then was the House the conservative outlier on domestic policy generally, but the Senate the blocking outlier on civil rights? 3 February 12: Norms and roles Required: Donald R. Matthews, “The Folkways of the United States Senate: Conformity to Group Norms and Legislative Effectiveness,” American Political Science Review 53:4 (December 1959), 1064-89 Richard F. Fenno, Jr., “The House Appropriations Committee as a Political System,” American Political Science Review 56 (1962), 310-24 John F. Manley, “The House Committee on Ways and Means: Conflict Management in a Congressional Committee,” American Political Science Review 59:4 (December 1965), 927-39 Nelson W. Polsby, “The Institutionalization of the U.S. House of Representatives,” American Political Science Review 62 (1968), 144-68 Suggested: Roger H. Davidson, The Role of the Congressman (Pegasus: 1969) Kenneth Shepsle, “The Changing Textbook Congress,” in John Chubb & Paul Peterson (eds.), Can the Government Govern? (Brookings, 1989). A general picture of the post-World War II Congress rich in norms and roles. February 19 – Purposive politicians Required: David R. Mayhew, Congress: The Electoral Connection (Yale UP, original edition 1974; second edition with same text but new foreword and preface, 2004). Either edition is OK. Lots of used copies float around. Suggested: Richard F. Fenno, Jr., Congressmen in Committees (Little, Brown, 1973). Members are animated by three goals: reelection, power within Congress, making good public policy. Morris P. Fiorina, Congress: Keystone of the Washington Establishment (Yale UP, 1977). The reelection goal and its pork and casework consequences. R. Douglas Arnold, The Logic of Congressional Action (Yale UP, 1990). A reelection worry for members: the downstream “traceability” of their actions on Capitol Hill. Diana Evans, Greasing the Wheels: The Use of Pork Barrel Projects to Build Majority Coalitions in Congress (Cambridge UP, 2004). The politics of earmarking. Justin Grimmer, Solomon Messing & Sean J. Westwood, “How Words and Money Cultivate a Personal Vote: The Effect of Legislator Credit Claiming on Constituent Credit Allocation,” American Political Science Review 106:4 (November 2012), 703-19. A current look at credit claiming. 4 Justin Grimmer, “Appropriators Not Position Takers: The Distorting Effects of Electoral Incentives on Congressional Representation,” forthcoming American Journal of Political Science. A current look at position taking. February 26 – Representative styles Required: Richard F. Fenno, Jr., Home Style: House Members in Their Districts (original Little, Brown edition 1978; Longman edition with same text and new foreword, 2003). Either edition is OK. Suggested: Richard F. Fenno, Jr., Going Home: Black Representatives and Their Constituents (University of Chicago Press, 2003). Same kind of study. Jane Mansbridge, “Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? A Contingent ‘Yes’,” Journal of Politics 61 (1999), 628-57 Warren E. Miller & Donald E. Stokes, “Constituency Influence in Congress,” American Political Science Review 57 (1963), 45-56. A classic article. A very different approach. Roll call positions are matched to district opinion. March 5 – Formal theories: the committees, the floor, the parties Required: Barry R. Weingast & William J. Marshall, “The Industrial Organization of Congress,” Journal of Political Economy 96:1 (1988), 132-63. A classic statement of distributive theory. Keith Krehbiel, Information and Legislative Organization (University of Michigan Press, 1992), chapter 3. Information theory lodged as a critique of distributive theory. Gary W. Cox & Mathew D. McCubbins, Setting the Agenda: Responsible Party Government in the U.S. House of Representatives (Cambridge UP, 2005), chapters 1, 2. Party cartel theory. Suggested: Kenneth A. Shepsle & Barry R. Weingast, “Positive Theories of Congressional Institutions,” pp. 5-35 in Shepsle & Weingast, Positive Theories of Congressional Institutions (University of Michigan Press, 1995). A discussion of the genre. Craig Volden & Alan E. Wiseman, “Formal Approaches to the Study of Congress,” chapter 3 in Schickler & Lee, Oxford Handbook Eric Schickler & Kathryn Pearson, “Agenda Control, Majority Party Power, and the House Committee on Rules,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 34:4 (2009), 455-91. Takes exception to party cartel theory, at least for the mid-twentieth century. 5 Keith Krehbiel, “Where’s the Party?” British Journal of Political Science 23 (1993), 235-66. Emphasizes policy control by the median House member regardless of party. John M. Carey, “Political Institutions, Competing Principals, and Party Unity in Legislative Voting,” 2007 paper. Available online. In general in presidential systems (not just the USA), what edges do legislative majority parties enjoy over minority parties? March 26 – Ideological dimensions Required: Keith T. Poole & Howard Rosenthal, Ideology and Congress (Transaction, 2007), chapters 1-4 Suggested: Poole has a website, Voteview.com Nolan McCarty, “Measuring Legislative Preferences,” chapter 4 in Schickler & Lee, Oxford Handbook Frances E. Lee, Beyond Ideology: Politics, Principles, and Partisanship in the U.S. Senate (University of Chicago Press, 2009). Is it policy or power that the members struggle over? April 2 – Divided versus unified party control Required: David R. Mayhew, Divided We Govern: Party Control, Lawmaking, and Investigations, 1946-2002 (Yale UP, second edition, 2005) Suggested: Sarah A. Binder, “The Dynamics of Legislative Gridlock, 1947-96,” American Political Science Review 93:3 (September 1999), 519-33. Argues that this kind of study needs a denominator for policy demand; just looking at deviation from policy stability isn’t enough. Charles R. Shipan, “Does Divided Government Increase the Size of the Legislative Agenda?” in Scott Adler & John Lapinski (eds.), The Macro-Politics of Congress (Princeton UP, 2006). The answer seems to be yes, at least somewhat. David C. W. Parker & Matthew Dull, “Divided We Quarrel: The Politics of Congressional Investigations, 1947-2004,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 34:3 (August 2009), 319-45. Takes issue with Mayhew. Joshua D. Clinton & John S. Lapinski, “Measuring Legislative Accomplishment, 1887-1994,” American Journal of Political Science 50:1 (January 2006), 232-49. Rigorous and Imaginative study. 6 Eric M. Patashnik, “After the Public Interest Prevails: The Political Sustainability of Policy Reform,” Governance 1:2 (April 2003), 203-34. What happens to laws once they pass? April 9 – Supermajority pivots Required: Keith Krehbiel, Pivotal Politics: A Theory of U.S. Lawmaking (University of Chicago Press, 1998), chs. 1-3. Steven S. Smith, “The Senate Syndrome,” in Issues in Governance Studies (Brookings, 2010). The chamber’s increasing difficulty making decisions since 2000. Suggested: Gregory Koger, Filibustering: A Political History of Obstruction in the House and Senate (University of Chicago Press, 2010), chs. 1-4, 6, 8. Smart authoritative history. Kathleen Bawn & Gregory Koger, “Effort, Intensity and Position Taking: Reconsidering Obstruction in the Pre-Cloture Senate,” Journal of Theoretical Politics 20:1 (2008), 67-92. A theory of intensity. Gregory J. Wawro & Eric Schickler, “Where’s the Pivot? Obstruction and Lawmaking in the Precloture Senate,” American Journal of Political Science 48 (2004), 758-74. Obstruction and its absence in earlier days. David R. Mayhew, Partisan Balance (Princeton UP, 2011), pages 142-64. Senate majority rule or its absence since World War II looked at empirically. April 16 – Institutional instability Required: Eric Schickler, Disjointed Pluralism: Institutional Innovation and the Development of the U.S. Congress (Princeton UP, 2001), chapters 1-2, 4-6, Epilogue Suggested: David W. Rohde, Parties and Leaders in the Postreform House (University of Chicago Press, 1991). A theory of conditional party leadership strength; centers on House procedural reforms in the 1960s-1980s. Erik Schickler, Eric McGhee & John Sides, “Remaking the House and Senate: Personal Power, Ideology, and the 1970s Reforms,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 28:2 (2003), 297-333. What were the coalitions that spurred the procedural reforms? Julian E. Zelizer, On Capitol Hill: The Struggle to Reform Congress and Its Consequences (Cambridge UP, 2004). A history of procedural reform efforts since the 1940s. 7 April 23 – Homeostatic representation Required: Joseph Bafumi & Michael C. Herron, “Leapfrog Representation and Extremism: A Study of American Voters and Their Members in Congress,” American Political Science Review 104:3 (August 2010), 519-42. David W. Brady, Morris P. Fiorina & Arjun S. Wilkins, “The 2010 Elections: Why Did Political Science Forecasts Go Wrong?” PS: Political Science and Politics 44:2 (April 2011), 247-50 Suggested: HeMin Kim, G. Bingham Powell, Jr. & Richard C. Fording, “Electoral Systems, Party Systems, and Ideological Representation,” Comparative Politics 42:1 (January 2010), 167-85. Single-member-district systems encourage the Bafumi/Herron pattern. Morris P. Fiorina, Divided Government (Longman, second edition, 2002). The idea of voter “balancing.” Robert S. Erikson, “Explaining Midterm Loss: The Tandem Effects of Withdrawn Coattails and Balancing,” Yale American Politics Workshop paper, October 27, 2010, available online Gary C. Jacobson, “The 1994 House Elections in Perspective,” Political Science Quarterly 111 (1996), 203-23. Policy blowback in the 1994 midterm. John Ferejohn, “A Tale of Two Congresses: Social Policy in the Clinton Years,” chapter 2 in Margaret Weir (ed.), The Social Divide (1998). More on policy blowback, in the 1994 and 1996 elections. Christian R. Grose & Bruce I. Oppenheimer, “The Iraq War, Partisanship, and Candidate Attitudes,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 32 (2007), 531-57. More policy blowback, in the 2006 midterm. Robert S. Erikson, Michael B. MacKuen & James A. Stimson, The Macro Polity (Cambridge UP, 2002), chapter 9. The leading source on dynamic representation, or homeostatic kickback, in U.S. elections and policymaking. 8