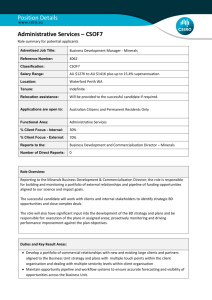

1. Further development of BecA governance arrangements. The

advertisement