File

advertisement

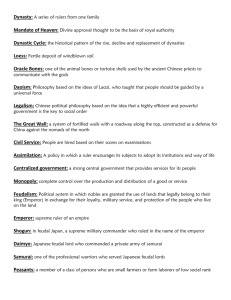

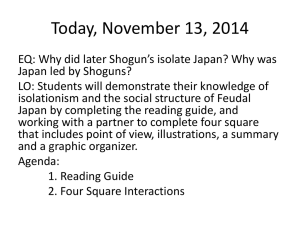

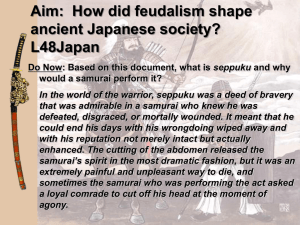

The samurai (or bushi) were the warriors of pre-modern Japan. They later made up the ruling military class that eventually became the highest ranking social caste of the Edo Period (1603-1867). Samurai employed a range of weapons such as bows and arrows, spears and guns, but their main weapon and symbol was the sword. Samurai were supposed to lead their lives according to the code of bushido ("the way of the warrior")., Bushido stressed concepts such as loyalty to one's master, self-discipline and respectful, ethical behaviour. The Origin of the Samurai: The samurai, a class of highly skilled warriors, gradually developed in Japan from 646 A.D. Heavy new taxes meant that many small farmers had to sell their land and work as tenant farmers. Meanwhile, a few large landholders amassed power and wealth, creating a feudal system similar to medieval Europe's. As in Europe, the new feudal lords needed warriors to defend their riches. Thus, the samurai warrior (or "bushi") was born. Taken from http://asianhistory.about.com/od/warsinasia/p/SamuraiProfile.htm The two most powerful of these landowning clans, the Minamoto and Taira, eventually challenged the central government and battled each other for supremacy over the entire country. Minamoto Yoritomo emerged victorious and set up a new military government in 1192, led by the shogun or supreme military commander. The samurai would rule over Japan for most of the next 700 years. During the chaotic era of warring states in the 15th and 16th centuries, Japan splintered into dozens of independent states constantly at war with one another. Consequently, warriors were in high demand. The country was eventually reunited in the late 1500s, and a rigid social caste system was established during the Edo Period that placed the samurai at the top, followed by the farmers, artisans and merchants respectively. During this time, the samurai were forced to live in castle towns, were the only ones allowed to own and carry swords and were paid in rice by their daimyo or feudal lords. Masterless samurai were called ronin and caused minor troubles during the 1600s. Relative peace prevailed during the roughly 250 years of the Edo Period. As a result, the importance of martial skills declined, and many samurai became bureaucrats, teachers or artists. Japan's feudal era eventually came to an end in 1868, and the samurai class was abolished a few years afterwards. Taken from http://www.nextsportstar.com/blogs/5444/302/the-samurai Samurai Culture The culture of the samurai was grounded in the concept of bushido - "the way of the warrior." The central tenets of bushido are honour and freedom from the fear of death. A samurai was legally entitled to cut down any commoner who failed to honour him (or her) properly. A warrior imbued with bushido spirit would fight fearlessly for his master, and die honourably rather than surrender in defeat. Out of this disregard for death, the Japanese tradition of seppuku evolved: defeated warriors (and disgraced government officials) would commit suicide with honour by ritually disembowelling themselves with a short sword. Samurai Weapons Early samurai were archers, fighting on foot or horseback with extremely long bows (yumi). They used swords mainly for finishing off wounded enemies. After the Mongol invasions of 1272 and 1281, the samurai began to make more use of swords, as well as poles topped by curved blades called naginata, and spears. Samurai warriors wore two swords, together called daisho - "long and short." The katana, a curved blade over 24 inches long, was suitable for slashing, while the wakizashi, at 12-24 inches, was used for stabbing. In the late 16th century, non-samurai were forbidden to wear the daisho. Samurai wore full body-armour in battle, often including a horned helmet. Women Maintaining the household was the main duty of samurai women. This was especially crucial during early feudal Japan, when warrior husbands were often travelling abroad or engaged in clan battles. The wife, or okugatasama (meaning: one who remains in the home), was left to manage all household affairs, care for the children, and perhaps even defend the home forcibly. For this reason, many women of the samurai class were trained in wielding a polearm called a naginata or a special knife called the kaiken in an art called tantojutsu (lit. the skill of the knife), which they could use to protect their household, family, and honor if the need arose. Traits valued in women of the samurai class were humility, obedience, self-control, strength, and loyalty. Ideally, a samurai wife would be skilled at managing property, keeping records, dealing with financial matters, educating the children (and perhaps servants, too), and caring for elderly parents or in-laws that may be living under her roof. Confucian law, which helped define personal relationships and the code of ethics of the warrior class required that a woman show subservience to her husband, filial piety to her parents, and care to the children. Too much love and affection was also said to indulge and spoil the youngsters. Thus, a woman was also to exercise discipline. Though women of wealthier samurai families enjoyed perks of their elevated position in society, such as avoiding the physical labour that those of lower classes often engaged in, they were still viewed as far beneath men. Women were prohibited from engaging in any political affairs and were usually not the heads of their household. This does not mean that samurai women were always powerless. The source of power for women may have been that samurai looked down upon matters concerning money and left their finances to their wives. As the Tokugawa period progressed more value became placed on education, and the education of females beginning at a young age became important to families and society as a whole. Marriage criteria began to weigh intelligence and education as desirable attributes in a wife, right along with physical attractiveness. Though many of the texts written for women during the Tokugawa period only pertained to how a woman could become a successful wife and household manager, there were those that undertook the challenge of learning to read, and also tackled philosophical and literary classics. Nearly all women of the samurai class were literate by the end of the Tokugawa period. Women section taken from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samurai