Transnational Movements-1 - Makerere Institute of Social

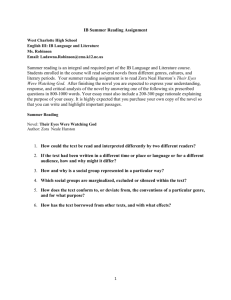

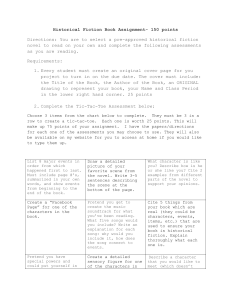

advertisement