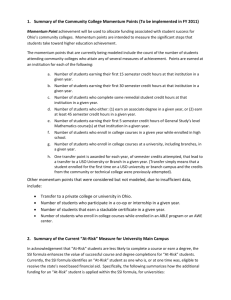

Teaching At-risk Students with Technology

advertisement

Teaching At-risk Students with Technology David Rutledge and Binod Gurung New Mexico State University United States rutledge@nmsu.edu binod@nmsu.edu In this paper, we present how at-risk students engage with technology in their learning. We report findings from a phenomenological study that explored the educational digital engagement – learning engagement with technology – of five at- risk students attending a public alternative high school. Findings show that their educational digital engagement was varied and differential leading to three different learning paths – corrective, transitional, and transformative. Pedagogical implications are discussed. Introduction At-risk students are academically low performing students, who are at the risk of educational failure lacking behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement with school and the schoolwork (Carver & Lewis, 2010; Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004). As these students have varying learning needs (e.g., low academic achievement, behavioral infractions, and lack of persistence), the schools have to provide them with individualized instructional and learning opportunities (Hollowell, 2009). In turn, this demands teachers to have knowledge about how these at-risk students learn with technology. There is general perception that when at-risk students are engaged with technology such as computers and the Internet, their diverse learning needs are met (Frey & Fisher, 2004; Knezek & Christensen, 2007). This perception is built on the idea that digital engagement – the learning engagement with and by digital tools and resources– provides students with individual learning experiences such as content customization, credit recovery, anytime and anywhere access, and self-paced leaning to name a few (Hew & Brush, 2007; National Educational Technology Plan, 2010). But studies show that the impact of technology on at-risk students is often minimal, problematic, and ineffective or at the best, mixed results being differentially effective to different students (Edmunds, 2008; Girod, Martineau, & Yong, 2004; Neil & Mathews, 2009; Wenglinsky, 1998). This is simply because these students are also the at-risk computer users having low level of technology skills (Edmunds, 2008) and computer self-efficacy (Moos & Azevedo, 2009). These students use technology for development of skills and drill and practice when compared to their regular counterparts, who use technology for creativity and critical thinking (Edmunds, 2008; Wenglinsky, 1998). Furthermore, these at-risk, low performing students need to find and evaluate information efficiently and effectively from the virtually seamless online repository while quickly adapting to their personal learning goals (Alexander & Fox, 2004; Grabinger, Dunlap, & Duffield, 1997). In these mixed and problematic contexts described above, it is important for teachers to explore how these at-risk students engage with technology to learn and subsequently construct their individual learning experiences. The present phenomenological study investigates the educational digital engagement of some at-risk students by exploring their learning experiences with technology. Theoretical Framework Currently, students’ use technology can be described within the “low-level” and “high-level” use of technology (Cuban, Kirkpatrick, & Peck, 2001). The low-level use of technology is described as the minimal use of computers (or any other kind of technologies) such as for typing, Internet searching, skills development, and drill practice (Cuban, Kirkpatrick, & Peck; Wenglinsky, 1998). On the other hand, the high-level use of technology involves using computers as “mindtools” or intellectual partners, working in collaboration, engaging in multimedia productivities, and other types of technology-mediated cognitive activities for the mastery of content, engaged learning, and the development of expertise in the subject matter (Cuban, Kirkpatrick, & Peck; ISTE, 2007; Jonassen, 2006). The notion of educational digital engagement is based on the conceptual framework of “school engagement” (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004). And the school enagment is interpreted as “the attention, interest, investment, and effort students expend in the work of school” (Marks, 2000, p. 155) across students’ academic, behavioral, and emotional dimensions (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004). In this study, behaviorally, the at-risk students’ conducts, persistence, and participation are examined within their digital engagement inside the classroom. Emotionally, the students’ interest, boredom, and emotional attachment (e.g., values, beliefs, and attitudes) to school and the schoolwork are explored. And cognitively, the students’ use of technology is examined whether it is at the “low-level” or “high-level.” Context The study was conducted at a public alternative high school, South West Alternative High School (SWAHS) – a pseudonym. SWAHS was the only public alternative high school serving at-risk students in the district. At SWAHS, there were 183 students enrolled in the school year 2010-2011 when the district had approximately 24,530 students housed in its 35 schools – 24 elementary, 7 middle, 4 high schools, and 1 vocational school in the same school year. The school had developed a technology-integrated Triad model and implemented it in teaching, learning, curriculum, and assessment. The model involved three components – one third direct instruction, one-third self-regulated one-to-one computer-based learning, and the final third is a project-based learning that culminates the former two thirds. The thirds were allocated with the equal amount of time for each based on the daily or weekly instructional routine. Utilizing the various technologies available in the school, the model was developed with a school wide collaborative effort involving teachers, administrators, and the district technology-integration specialist. Method and Data The study was designed using transcendental phenomenological method (Husserl, 1970; Moustakas, 1994). Employing the purposeful sampling method to capture the “maximum variation” such as grade level, gender, and ethnic diversity (Creswell, 2007), five participants were selected. The participants’ educational digital engagement was explored using the in-depth “three-interview series” (Seidman, 1998) and close observation (Moustakas, 1994; van Mannen, 1990). The data were analyzed using the four general steps of phenomenological data analysis: horizonalization, individual textural descriptions, individual structural descriptions, and composite structural descriptions (Moustakas, 1994). First three steps were utilized as the procedural stages to develop composite structural descriptions – the descriptions that provide participant’s lived experiences as a group of their educational digital engagement. Findings Each participant had their own trajectory of learning with digital tools and resources. The participants’ educational digital engagement was proactive, multi-faceted, and also problematic. Overall, their educational digital engagement can be categorized in three different learning paths: corrective, transitional, and transformative. Corrective path: Students in the corrective path need overall improvement in their learning engagement with technology. When viewed from school engagement perspective (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004), they tend to have problems in behavioral, emotional, and cognitive dimensions. As an example, below is presented a case of Participant 3 -- a Hispanic, male, and junior at SWAHS -- who was in a corrective path. Participant 3 was taking two online courses and completing his assignments and projects for his face-to-face Language Arts class. But, he was easily disoriented even before completing a passage from the online readings. He was so disoriented that he did a number of things without any purpose or plausible reason such as checking out headphones, moving around, trying to “help” friends, scanning music on his MP3 player, and so forth. He also disrupted the class by making unnecessary comments to his classmates. If he did not do these things, he stared blankly, rested his head on the desk, or hummed. Participant 3 did attempt his tests including the timed and graded tests on the computer. Most of the time, he randomly clicked the answer and tried to move on to the “next level.” Generally, he did not read any feedback that was generated by the computer nor did he take any make-up, remedial or diagnostic tests that were designed to scaffold his learning. For instance, in his online history course, there were plenty of media archives and supplemental readings and suggested websites. The laptops also had wireless Internet access. But he did not seem to realize the digital learning resources provided for him to support his learning. Despite the fact that he was placed in an alternative school and his own renewed intention to engage, learn, and pass the class, Participant 3 put forth little effort and virtually no interest to access and to complete his coursework. He just wanted to get by with his assignments. Similarly, his digital engagement could be characterized as the lacking of emotional engagement (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004) including the interest in schoolwork and joy of doing tasks using computers. Despite the fact that Participant 3 had viewed the computer as a “useful tool” for learning, his overall cognitive engagement with technology was at the low-level such as typing assignments, Internet searches, skills development, and drill practice (Cuban, Kirkpatrick, & Peck, 2001; Edmunds, 2008). Transitional path: Students in this path need some improvement such as developing and maintaining a “flow,” a deep immersion, in their learning and with the learning environment. For instance, these Participants 2 and 3 below provide how the students in a transitional path engage with technology. Participant 2, a Caucasian, female, and senior demonstrated positive conduct for using technology in learning, in addition she adhered to classroom rules and regulations. She was often quiet, spoke only when necessary, and kept pretty much to herself. Unlike in the past in her regular high school, she did not skip the school. However, her involvement in learning was partially problematic. She made some good efforts to learn and persisted in learning until she completed her assignments and projects. She did not have sustained enthusiasm or excitement for learning beyond completing her tasks. She seemed to lack a zeal for leaning. She completed her reading, writing, and other online assignments in almost mechanical fashion, without putting much effort and interest. Her concentration and attention were diverted by her digital habits of multitasking (e.g., texting and listening to music during the class). Besides multitasking, she was also occasionally seen playing games on the computer and checking her photographs. Participant 5, a Hispanic, female, and senior was using the computer for her learning, at least a third of the time in the classroom, as the Triad model at SWAHS required. Similar to the Participant 2, she did not have any behavioral or emotional issues while using computers during the class. But she lacked enthusiasm for learning such that after completing her projects and assignments, she simply stayed in the class without doing anything, but waiting to be the class period over. Similarly, her educational engagement was limited at the “low-level” use of technology; for example, she was using her computer and the Internet for looking up information and word meaning, and not for collaboration and multimedia productivities. Transformative path: Students in this path proactively utilize various technologies in their learning. These students not only can demonstrate what they are learning, but also dynamically create learning opportunities for themselves. Participant 1, a sophomore and female, came from a mixed racial background (Caucasian father and Hispanic mother). She used the computers efficiently for her academic achievement. Usually she was into the task and completed her coursework enthusiastically, often ahead of the designated time and pacing schedule. She did not exhibit any computer-related or classroomrelated disruptive behavior. She was smooth and silent in the class. Whenever the class was noisy, she would step out of the class and go to the school’s Cybercafé to find a quieter learning space for herself. She positively perceived taking the online courses and using computers for learning within the pedagogical design of the Triad model. Her positive perception and attitude toward using technology, combined with the digital tools and resources made available through the “learning ecologies” of SWAHS and the Triad model, lent herself to a “newfound educational engagement.” In the newfound educational engagement, she utilized technologies in the three “substantive” ways: as means to generate “new educational engagement ” (e.g., for taking advanced placement courses and pre-college credit courses such as higher algebra and science through the Odysseyware® online learning system); as creating learning environment that provides “extensions” of her learning opportunities (e.g., accessing online courses from home and taking as many as six credits per semester for credit recovery); and as scaffolding tools (e.g., doing online research to “reinforce” what she had learned and using Odysseyware® feedback system). Another Participant 5, a senior and male, came from mixed racial background (Brazilian father and Caucasian mother). He had substantial knowledge about “hard” and “soft” technologies. He had knowledge about the computer hardware such as the processor, memory, and hard disk and the configuration of the hardware. He also had knowledge about software aspects of the computer such as online video games and multimedia production. His educational digital engagement can be described as progressive and selective. It was progressive that, once doomed to failure in his middle and early high school years, he was excelling in all the core content area subjects. But, more importantly, he was taking more and more advanced courses/electives that were aligned to his technology related competencies and interests. For instances, he was taking the mass media class as his elective in the school and the game designing course in the local community college. Conclusion and Implications Some studies in the past have shown that the use of technology for at-risk students is differentially effective to different students (e.g., Dyrnaski et al, 2007; Edmunds, 2008; Girod, Martineau, & Yong, 2004; Neil & Mathews, 2009). But there is little understanding what those differential impacts of technology in their learning are. This study offers insights into the differential impacts of technology by identifying three different learning paths – corrective, transitional, and transformative – that exist within the educational digital engagement of at-risk students. This study also undercuts the mistakenly perceived difficulty by teachers about teaching at-risk students, who have “stigmatized” images (McNulty & Roseboro, 2009) such as “inactive learners” (Torgesen, 1982), struggling readers (Franzak, 2006), and delinquent youths (Kim & Taylor, 2008), all thwarted by the “deficit” characteristics. Findings demonstrate that these students, when provided with meaningful learning engagement with or without technology, can succeed, even excel academically. Finally, we hope that these three differential paths inform not only the educational digital engagement of atrisk students, but also the general K-12 students’. We encourage that teachers and researchers should develop pedagogies and research agendas seeking to transform students from corrective and transitional trajectories to a transformative educational digital engagement path. References Alexander, P. A., & Fox, E. (2004). A historical perspective on reading research and practice. In R.B. Ruddell & N.J. Unrau (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (5th ed.), (pp. 33– 68). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Carver, P. R., & Lewis, L. (2010). Alternative schools and programs for public school students atrisk of educational failure: 2007–08 (NCES 2010–026). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. Cuban, L., Kirkpatrick, H., & Peck, C. (2001). High access and low use of technologies in high school classrooms: Explaining an apparent paradox. American Educational Research Journal, 38(4), 813–834. Dynarski, M., Roberto, A., Heaviside, S., Novak, T., Carey, N., Campuzano, L., Means, B., Murphy, R., Penuel, W., Javitz, h., Emery, D., & Sussex, W. (2007). Effectiveness of Reading and Mathematics Software Products: Findings from the First Student Cohort, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, 2007. Edmunds, J. A. (2008). Using alternative lenses to examine effective teachers’ use of technology with low-performing students. Teachers College Record, 110(1), 195–217. Franzak, Z. K. (2006). Zoom: A review of the literature on marginalized adolescent readers, literacy theory, and policy implications. Review of Educational Research, 76(2), 209–248. Fredricks, J.A., Blumenfeld, P.C., & Paris, A.H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59-109. Frey, N., & Fisher, D. (2004). Using graphic novels, anime, and the internet in an urban high school. English Journal, 93(3), 19-25. Girod, M., Martineau, J., & Yong, Z. (2004). After-school computer clubhouses and at-risk teens. American Secondary Education, 32(3), 63-76. Grabinger, R.S., Dunlap, J.C., & Duffield, J.A. (1997). Rich environments for active learning in action: Problem-based learning. Association for Learning Technology Journal, 5(2), 5-17. Hew, K. F., & Brush, T. (2007). Integrating technology into K-12 teaching and learning: Current knowledge gaps and recommendations for future research. Educational Technology Research and Development, 55, 223-252. Hollowell, M. (2009). The forgotten room: Inside a public alternative school for at-risk youth. New York: Lexington Books. Husserl, E. (1970). The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology (D. Carr, Trans). Evanston: Northwestern University Press. Jonassen, D. H. (2006). Modeling with technology: Mindtools for conceptual change (3rd ed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill/Prentice Hall. Kim, J-H., & Taylor, K. A. (2008). Rethinking alternative education to break the cycle of educational inequality and inequity. The Journal of Educational Research, 101(4), 207-219. Knezek, G., & Christensen, R. (2007). Effect of technology-based programs on first- and secondgrade reading achievement. Computers in the Schools, 24(3/4), 23-41. DOI: 10.130(}/J()25v24n03 03. Marks, H. (2000). Student engagement in instructional activity: Patterns in the elementary, middle, and high school years. American Education Research Journal, 37(1), 241-270. McNulty, C. P., & Roseboro, D. L. (2009). I'm not really that bad: Alternative school students, stigma, and identity politics. Equity & Excellence in Education, 42(4), 412–427 Moos, D.C., & Azevedo, R. (2009). Learning with computer-based learning environments: A literature review of computer self-efficacy. Review of Educational Research, 79(2), 576–600. Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. National Education Technology Plan (2010). Transforming American education learning: powered by technology. Washington, DC: Author. Neil, M., & Mathews, J. (2009). Does the use of technological interventions improve student academic achievement in mathematics and Language Arts for an identified group of At-risk middle school students? Southeastern Teacher Education Journal, 2(1), 57-65. Seidman, I. (1998). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences. New York: Teachers College Press. Torgesen, J. K. (1982). The learning disabled child as an inactive learner: Educational implications. Topics in Learning and Learning Disabilities, 2, 45–52. van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. New York: State University of New York. Wenglinsky, H. (1998). Does it compute? The relationship between educational technology and student achievement in mathematics. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.