England and France

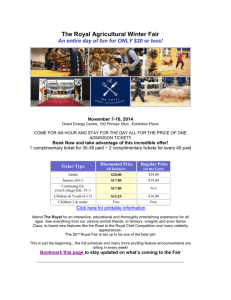

advertisement

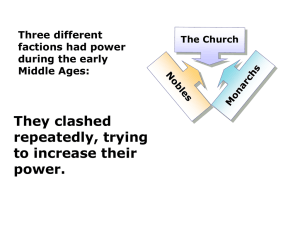

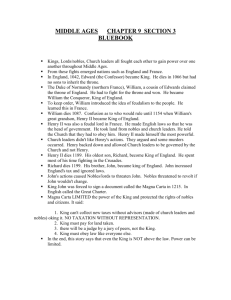

Chapter 9: The High Middle Ages(1050-1450) Section 1: Growth of Royal Power England and France Objective: Describe how monarchy in England and France increased royal power Pgs 208-214 Strong Monarchy in England: During the Middle Ages, Angles, Saxons and the Vikings invading and settled on England. Feudalism developed, England rulers kept their kingdoms united. Norman conquests: In 1066, the Anglo-Saxon king Edwards died without an heir. His death triggers a power struggle. A council of the nobles chose Edwards brother-inlaw Harold to rule. Duke William of the Normans claimed the English throne. Duke William raised an army and won the backing of the pope. At the battle of Hastings, William and his Normans knights triumph over Harold. On Christmas day 1066, William assumed the throne. William takes control: William exerted his control over England. He granted fief, to the Church and his Normans lords, or barons. He required every vassal to swear first allegiance to him rather to the feudal lords. William had a complete census taken in 1086. The Domesday Book, which listed every castle, field, in England. Information in the Domesday Book helped William and his successors build an efficient system of tax collections. Increasing royal authority: In 1154 king Henry II, inherited the throne and broadened the system of the royal justice. He then sent out travelling justices to enforce the royal laws. The decisions of the royal courts became the basis for English common laws for all people. People chose royal courts over those nobles or the Church. Early juries: Under Henry II, England developed early jury systems. When travelling justice visited an area, local officials collected a jury, or group of men sworn to speak the truth. A tragic clash: Henry’s efforts to extend royal power to lead to bitter dispute with the Church. Henry claimed the right to try the clergy in royal courts. Thomas Becker, the archbishop of Canterbury and once a close friend of Henry’s fiercely oppose the king’s move. In 1170, four of Henry’s knights, believe they were doing Henry’s bidding, murdered the archbishop in his own cathedral. Henry’s denied any part in the attack. Evolving Tradition of Government: Later English rulers repeatedly clashing with the nobles and the Church. Most battles developed as a result of efforts by the monarchy to raising taxes or to impose royal authority over traditional feudal rights. John’s troubles: John’s reigns, faced three powerful enemies, King Philip II of France, Pope Innocent III and the English nobles. He lost his struggles with each. Ever since William the Conqueror, Norman rulers of England had held vast lands in France. In 1205, John suffered his first setback when he lost a war with Philip II and had to give up English held lands in Anjou and Normandy. Next, John battled with Pope Innocent III over selecting the new archbishop of Canterbury. When John attacked the Church, the Pope responded by excommunicate him. He also placed England under the interdict, a papal order that forbade Church service in an entire England. To save himself and his crown, John had to accept England as a fief of the papacy and pay a yearly fee to Rome. Observation Summaries the idea about government and law that emerges in England The Magna Carta: John angered his own nobles with heavy taxes and other abuse of power. In 1215, a group of rebellions barons cornered John and forced him to sign the Magna Carta or Charter. In this document, the king affirmed a long list of feudal rights. Protecting their own privileges, the barons including a few clauses recognising the rights of townspeople and their Church. The Magna Carta contains two basic ideas that in the long run would shape government tradition in England. First, it asserted that the nobles had certain rights. Granted to nobles were extended to all English citizens. Second, the Magna Carta made clear that the monarchy must obey the laws. The most significant clauses were those that protected the legal rights of the people. The king also agreed not to raise new taxes without first consulting his Great Council of lords and clergy. Growth of Royal Power in England and France Observation Describe how monarchy in France increased Royal Power. The Capetians: In 987, these feudal nobles elected Hugh Capt, the count Paris, to fill the vacant throne. They probably chose him because he was too weak to pose a threat to them. Hugh’s has his own lands, the Ile de France around Paris. Hugh and his heirs slowly increased royal power. First, they made the throne hereditary, passing from father to son. The Capetians enjoyed an unbroken succession for 300 years. Next, they added their lands by playing rival nobles against each other. They also won the support of the Church. Most important, the Capetians built an effective bureaucracy. Governments collected taxes and imposed royal law over king’s domain. By establishing orders, they added to their prestige and gained the barking of the new middle class of townspeople. Philip Augustus: An out speaking French of this period was Philip II, called Philip Augustus. Philip was shrewd able ruler. He strengthened royal government in many ways. Instead of appointing the nobles to the government position, he paid the middle class officials who would owe their loyalty to him. He granted charters too many new towns, organizing a standing army and introduced a new national tax. Philip also quadrupled royal land holdings. Through trickery, diplomacy and war, he brought English rules land in Normandy and Anjou under his control. He then began to take over southern France. Informed by pope that the Albigensian, heresy had sprung up in the south, he sent his knights to suppress it and add this vast area to his domain. Before his death in 1223, Philip had become the most powerful ruler in Europe. A model monarchy: Louis IX was the grandson of Philip II. Louis ascended to the throne 1226 and devoted to justice and rule. He expanding the royal courts, outlawed private wars and ended serfdom in his lands. Clash with the Pope: Louis’s grandson of Philip IV, ruthless expended royal power. He tied to collect new taxes from the French clergy. These effects led to a head-on clash with Pope Boniface VIII. The pope forbad Philip to tax the clergy without Papal consent. Philip counted by threatening to arrest the clergy who did not pay up. As their quarrel escalated Philip sent troops to sized Boniface. The pope escaped but he was badly beaten and died soon afterwards. The new pope moved the papal courts to the town of Avignon on the border of south France, to escape.