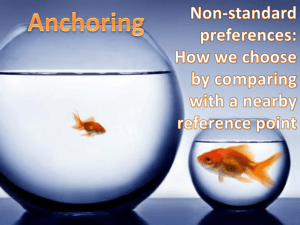

Anchoring -Law Review - Doron Teichman

advertisement