Darfur Community Peace-building and Conflict Resolution

advertisement

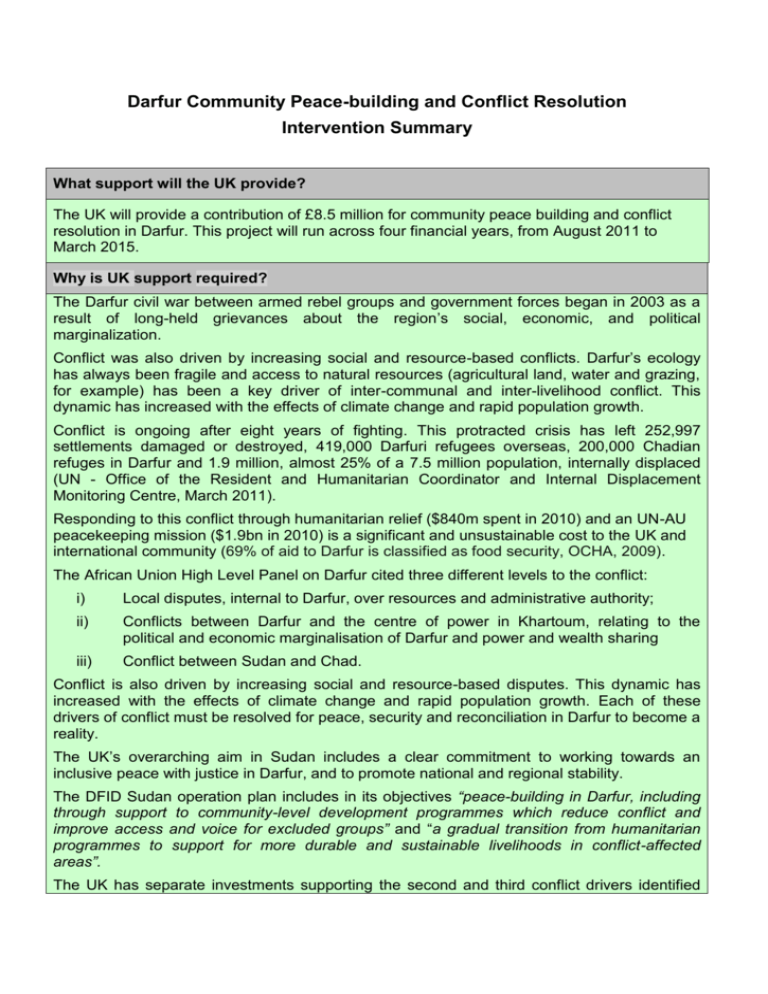

Darfur Community Peace-building and Conflict Resolution Intervention Summary What support will the UK provide? The UK will provide a contribution of £8.5 million for community peace building and conflict resolution in Darfur. This project will run across four financial years, from August 2011 to March 2015. Why is UK support required? The Darfur civil war between armed rebel groups and government forces began in 2003 as a result of long-held grievances about the region’s social, economic, and political marginalization. Conflict was also driven by increasing social and resource-based conflicts. Darfur’s ecology has always been fragile and access to natural resources (agricultural land, water and grazing, for example) has been a key driver of inter-communal and inter-livelihood conflict. This dynamic has increased with the effects of climate change and rapid population growth. Conflict is ongoing after eight years of fighting. This protracted crisis has left 252,997 settlements damaged or destroyed, 419,000 Darfuri refugees overseas, 200,000 Chadian refuges in Darfur and 1.9 million, almost 25% of a 7.5 million population, internally displaced (UN - Office of the Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator and Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, March 2011). Responding to this conflict through humanitarian relief ($840m spent in 2010) and an UN-AU peacekeeping mission ($1.9bn in 2010) is a significant and unsustainable cost to the UK and international community (69% of aid to Darfur is classified as food security, OCHA, 2009). The African Union High Level Panel on Darfur cited three different levels to the conflict: i) Local disputes, internal to Darfur, over resources and administrative authority; ii) Conflicts between Darfur and the centre of power in Khartoum, relating to the political and economic marginalisation of Darfur and power and wealth sharing iii) Conflict between Sudan and Chad. Conflict is also driven by increasing social and resource-based disputes. This dynamic has increased with the effects of climate change and rapid population growth. Each of these drivers of conflict must be resolved for peace, security and reconciliation in Darfur to become a reality. The UK’s overarching aim in Sudan includes a clear commitment to working towards an inclusive peace with justice in Darfur, and to promote national and regional stability. The DFID Sudan operation plan includes in its objectives “peace-building in Darfur, including through support to community-level development programmes which reduce conflict and improve access and voice for excluded groups” and “a gradual transition from humanitarian programmes to support for more durable and sustainable livelihoods in conflict-affected areas”. The UK has separate investments supporting the second and third conflict drivers identified above, including support for Darfur peace talks in Doha. However, there also needs to be a community-based, bottom-up approach to peace-building in Darfur, to create the conditions for local peace (stabilisation). This Business Case aims to address this gap. Funding will support communities in conflict to coalesce around a common agenda leading to reconciliation and peaceful coexistence at local level. The evidence suggests that the demand at the community level for such intervention is extremely high, with over 95% of Darfuris seeking mechanisms for nomads, farmers, and government to reconcile (‘Assessing Attitudes and Public Opinion in Darfur’, Albany Associates 2010). Localized peace can both transform and improve the lives of those affected. Between 2008 and 2010 almost 3,300 people died in as a direct result of conflict in Darfur. 48% of these were due to inter-tribal clashes. Of Darfur’s estimated 8,300 settlements, 36%, or 2,997 were damaged or destroyed, 2003-09. As a result the poverty and MDG data are very poor, even compared to elsewhere in Sudan. For example UN-RCSO office states that global chronic malnutrition for under-5s in Darfur (by stunting to height/age) ranges between 31.8 and 40.1%. Net secondary school attendance in Darfur is 14% (2008). It is understood that this intervention will have direct conflict and poverty impacts, including in terms of a decrease in the number of communities and people affected by conflict, a reduction in number of new IDPs cased by community based conflict, an increase in the number of IDPs able and willing to return to their original homes and improvements in access to basic services, particularly health, education, water and sanitation. The preferred option for UK fund management is a UNDP administered multi-donor trust fund, which has proven its ability to deliver results on the ground. What are the expected results? This intervention is based on the following theory of change: That through the provision of: i. Effective community-level conflict resolution and prevention platforms; ii. That help communities cooperate over disputed livelihoods assets, income generating opportunities, and access to natural resources; iii. Backed up by projects that allow these communities to gain equally from more equitable and sustainable growth; Communities are able to live in peace (stabilised) for a reasonable period. iv. The evidence of what works and the appetite for peace at a community level will be fed into wider peace dialogues and to those investing in Darfur, be they Sudanese government, donor, NGO or private sector, resulting in increased pressure for a comprehensive peace agreement and more conflict sensitive programming by others. The outcome of all this will be “more Darfur communities stabilised, with trust and confidence between communities restored, paving the way towards early recovery” as measured by an increase in the percentage of community members sampled declaring that trust and confidence is restored and an increase from 60% to 90% in the percentage of tribal/civil society leaders sampled agreeing to a common and/or collaborative approach on how to address the root causes of conflict. The impact will be “an increase in local level peace and stability in Darfur, supporting more inclusive, sustainable and successful Darfur-wide peace negotiations”. Darfur Community Peace-building and Conflict Resolution The Strategic Case A. Context and need for DFID intervention Context: The Darfur civil war between armed rebel groups and government forces began in 2003 as a result of long-held grievances about the region’s social, economic, and political marginalization. Conflict is ongoing after eight years of fighting. This protracted crisis has left 252,997 settlements damaged or destroyed, 419,000 Darfuri refugees overseas, 200,000 Chadian refuges in Darfur and 1.9 million, almost 25% of a 7.5 million population, internally displaced (UN - Office of the Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator and Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, March 2011). Responding to this conflict through humanitarian relief ($840m spent in 2010) and an UN-AU peacekeeping mission ($1.9bn in 2010) is a significant and unsustainable cost to the UK and international community (69% of aid to Darfur is classified as food security, OCHA, 2009). 4.9 million people in Darfur are reliant on humanitarian assistance (UN Sudan Work plan 2011, p.58). The need: The African Union High Level Panel on Darfur, in 2010, cited three different levels to the ongoing conflict: i) local disputes, internal to Darfur, over resources and administrative authority; ii) Conflicts between Darfur and the centre of power in Khartoum, relating to the political and economic marginalisation of Darfur and power and wealth sharing; and iii) An internationalised conflict (Darfur borders and has impacted and been influenced by actions in Chad, Libya and the Central African Republic) Conflict is also driven by increasing social and resource-based disputes. Darfur’s ecology has always been fragile and access to natural resources (agricultural land, water and grazing, for example) has been a key driver of inter-communal and inter-livelihood conflict. This dynamic has increased with the effects of climate change and rapid population growth. Each of these drivers of conflict must be resolved for peace, security and reconciliation in Darfur to become a reality. Darfur is not however homogeneous. Some areas continue to experience active conflict whereas others are more stable. In other areas communities have successfully brokered local-level peace deals, however as the conflict has progressed, these have become harder to deliver, as different tribes and communities are increasingly divided and native and particularly government authorities have gradually lost credibility as peace brokers. Efforts to support the conditions for local, community-based peace are an essential part of the package required to support a comprehensive and sustainable peace agreement for Darfur. UK and DFID role: HMG’s overarching aim in Sudan is to support “a Sudan at peace with its neighbours, with accountable institutions and able to provide security for its people” (Sudan Strategy Refresh, 2010). This strategy includes a clear commitment to working towards an inclusive peace with justice in Darfur, and to promote national and regional stability. The DFID Sudan Operational Plan includes in its objectives “peace-building in Darfur, including through support to community-level development programmes which reduce conflict and improve access and voice for excluded groups” and “a gradual transition from humanitarian programmes to support for more durable and sustainable livelihoods in conflictaffected areas”. The UK has separate investments supporting the second and third conflict drivers identified above, specifically: support for Darfur peace talks (led by the Joint AU-UN Mediation Support Team); a more inclusive national constitution and political system (led by Conflict Dynamics International); and dialogue in support of a PRSP that results in increased funding for substate and local governments in Sudan’s peripheries. However, there also needs to be a community-based, bottom-up approach to peace-building in Darfur, to create the conditions for local peace (stabilisation). This Business Case aims to address this gap. Funding will support communities in conflict to coalesce around a common agenda leading to reconciliation and peaceful coexistence at local level. Demand for support: The evidence suggests that the demand at the community level for such intervention is extremely high, with over 95% of Darfuris seeking mechanisms for nomads, farmers, and government to reconcile (‘Assessing Attitudes and Public Opinion in Darfur’, Albany Associates 2010). Evidence also suggests that Darfuris look towards their traditional, native leaders to play the leading role in such processes. 66.7% of Darfuris seek the involvement of tribal leaders in peace negotiations and these leaders, in their role as native administrators, are the group most trusted to mediate, over all other options, including Sudan government officials and internationals (Albany Associates 2010). Equally, there is a growing evidence base, that in the absence of an overarching peace agreement for Darfur, efforts to help communities cooperate over disputed livelihoods assets, income generating opportunities (IGAs) and access to natural resources, and / or gain equally from newly provided assets, IGAs or resources will significantly increase the sustainability of any local peace agreement (Darfur Community Peace and Stability Fund – Independent Annual Review, DFID, 2010). This approach is increasingly important due to rapidly growing population and livelihood pressures in Darfur. Over 52% of the population is under 17 years. It is the youth who tend to be unemployed or underemployed, frustrated and are more likely to be involved in fighting (Beyond Emergency Relief, UN-RCSO 2010). Equally the likelihood of a failed agricultural season in Darfur has already and is projected to, rapidly increase (from 20 to 80% between now and 2050, UN-RCSO 2010). Impact on conflict and poverty: Localized peace can both transform and improve the lives of those affected, and also create momentum for a broader peace agreement, by showcasing that peace is desired, achievable and what is required for peace to be delivered and sustained. Between 2008 and 2010 almost 3,300 people died in as a direct result of conflict in Darfur. 48% of these were due to inter-tribal clashes. Of Darfur’s estimated 8,300 settlements, 36%, or 2,997 were damaged or destroyed, 2003-09. As a result the poverty and MDG data are very weak, even compared to elsewhere in Sudan. The UN-RCSO office states the following: Global chronic malnutrition for under 5’s in Darfur (by stunting to height/age) ranges between 31.8 and 40.1%. Net secondary school attendance in Darfur is 14% (2008). 44% have access to improved drinking water (2006) and 26% to improved sanitation. Under 5 mortality in Darfur (per 1,000) is 104 (2008) and maternal mortality (per 100,000) is 1,142 (2008). Net primary school attendance is 58% (2006). It is understood that this intervention will have direct conflict and poverty impacts, including in terms of a decrease in the number of communities and people affected by conflict, a reduction in number of new IDPs cased by community-based conflict, an increase in the number of IDPs able and willing to return to their original homes and improvements in access to basic services, particularly health, education, water and sanitation. Consequences of not funding: If work in this area is not funded there will be direct impacts, in terms of an increase in community-level conflict in Darfur, highlighted by a likely increase in the number of deaths due to conflict, the number of IDPs displaced and a reduction in development indicators, such as access to basic services. Indirectly, there should be an increase in bottom-up momentum for a comprehensive peace agreement or for pro-poor, conflict sensitive spend by the Government of Sudan and others. Key stakeholders: If these proposed interventions succeed in establishing and sustaining peace, at the community level, the evidence base generated as regards what works and why should be fed into ongoing efforts for a comprehensive Darfur peace agreement and to those spending significant funds in Darfur. In Sudan, the Federal government officially transfers $2.6bn to State Governments, however only a small percentage of this is allocated to the three Darfur State Governments ($285m). Of this $285m, 84% is spent on salaries and basic operational costs (UN-RCSO 2010). If the evidence base from these interventions can be used to catalyse additional allocations of Federal funding to Darfur, or for more conflict sensitive spend by Darfur State governments, or other stakeholders (including nontraditional donors), then the benefits of such interventions would be increased multiple times. At present the major donors for this area of work in Darfur are the UK and Dutch. Without UK funding, technical, development and diplomatic leadership in promoting this approach such initiatives would likely significantly reduce in scale and quality. If future work has the goal of influencing and engaging others (as above) in supporting this approach then reliance on UK inputs will reduce. The evidence base: This Business Case draws on a significant quantitative and qualitative research base as referenced in the text and endnotesi. The case also builds from and the approach is supported by the internal analysis of the DFID Sudan policy team, represented by the Darfur Region Policy and Programming Framework paper. B. Impact and Outcome The Impact to which the programme aims to contribute will be “an increase in local level peace and stability in Darfur, supporting more inclusive, sustainable and successful Darfur wide peace negotiations”. In order to contribute towards this Impact, the directly attributable Outcome is “more Darfur communities stabilised, with trust and confidence between communities restored, paving the way towards early recovery” as measured by an increase from 30% to 85% of community members sampled declaring that trust and confidence is restored and an increase from 60% to 90% in the percentage of tribal/civil society leaders sampled agreeing to a common and/or collaborative approach on how to address the root causes of conflict. We expect to deliver this outcome and impact, through the provision of: Effective community-level conflict resolution and prevention platforms; o As measured by: an additional 100 community-based resolution mechanisms that are functioning effectively; Led by tribal and civil society leaders that have a stronger common understanding (75% to 95%) of reconciliation initiatives; Increasing by 25%, the percentage of community members with access to and satisfaction with reconciliation mechanisms; That help communities cooperate over disputed livelihoods assets, access to basic services, income generating opportunities and access to natural resources; o As measured by: 90 new, joint-managed education and health initiatives; 45 newly equipped or rehabilitated schools attended by combined communities; 170 new, jointly-managed, water resources (such as water points, hafirs, boreholes, water pumps) and; an increase by 350,000 in the number of people with reasonable access to primary health care services; Backed up by projects that allow these communities to gain equally from more equitable and sustainable growth; o As measured by: a 20% increase in enrolment in formal or non-formal (vocational) training by diverse communities; 30 new, or re-established markets that enable diverse communities to interact and cooperate; An additional 180 community initiatives that deliver collaborative livelihoods and income generating strategies; a 30% increase in commercial interactions between target sample communities. Darfur Community Peace-building and Conflict Resolution The Appraisal Case A. Determining Critical Success Criteria (CSC) Each CSC is weighted 1 to 5, where 1 is least important and 5 is most important based on the relative importance of each criterion to the success of the intervention. CSC Description Weighting (1-5) 1 Effective community-level conflict resolution and prevention platforms in Darfur are in place. 5 2 Increased cooperation between communities over disputed 5 livelihoods assets, income-generating opportunities and access to natural resources 3 Equitable and sustainable growth promoted, with particular 3 attention to ensuring that stabilised rural and urban areas remain stable 4 Evidence of effective grassroots peace building initiatives collected and fed in wider peace fora and Darfur agendas 2 B. Feasible options Option 1: Support to the UN-led Darfur Community Peace and Stability Fund [DCPSF] Phase II The DCPSF was established on the rationale that, alongside any progress at the Darfur peace talks in Doha, the deployment of UNAMID and humanitarian assistance, there needs to be a community-based, bottom-up approach to the stabilisation of Darfur and the creation of conditions for local peace and equitable and sustainable growth. DCPSF focuses on addressing the root causes of conflict at grass-root and locality (local government) level. It does this by promoting conflict sensitive approaches to stabilisation that aim to promote trust and confidence across diverse communities. In so doing, DCPSFsupported activities and processes enable diverse communities to coalesce around a common agenda leading to reconciliation and peaceful coexistence on a local level. To do this DCPSF programming has tended to be designed along two axes: i. Independently brokered processes of dialogue and consultation that lead to the restoration of trust and confidence amongst diverse communities; and ii. The delivery of material inputs (programmes and services) that respond to community needs, whilst underpinning processes of dialogue and consultation; Learning from reviews of Phase I regards improving sustainability of interventions (the length of time peace lasts between stabilised communities) DCPSFII will also cover equitable and sustainable growth initiatives that directly contribute to maintaining stability. Phase II also includes: iii. A focus on ensuring that the aggregated impact and learning from DCPSF-funded community-peace building is fed into and informs broader Darfur peace processes and is used to inform the way development funds are programmed by other stakeholders, particularly by GoS and international donors. iv. An evidence and capacity mapping component to fill key Darfur specific gaps in knowledge and understanding on issues including land management, gender and the interaction between native and local government administration; v. A capacity development component with a view to increase peace-building and monitoring and evaluation capacity skills of partner CSOs/NGOs. vi. Selected analytic work to provide more understanding of the context of the programme environment and to strengthen the impact of the of the programme through a study on the economic impact of the programme (the balance of the cost and benefits) and a review of the capacity of civil society in Darfur and its role in peace building. Additional information on DCPSFII is available in the DCPSFII Terms of Reference at Flag B. Option 2: Support to the USAID Darfur Security and Stabilization Initiative (DSSI), specifically Output 1 on Stabilization and 4 on Traditional Dispute Resolution The DSSI is a $5.8m fund designed to assist the African Union (AU) in developing an operational strategy to implement the goals and objectives of the AU High Level Panel on Darfur. Specifically to enhance peace and security efforts in Darfur. These activities are intended to complement, and be accomplished in parallel with, the AU/UN mediated political talks. DSSI was contracted via a USAID tender process to a US-based contractor AECOM. The contractor is tasked with providing technical and advisory support to AU initiatives in Darfur, specifically: i. Supporting AU stabilization projects in order to bolster local peace and security agreements. Stabilization projects in this case are seen as small-scale, rapidly implementable non-military projects, which help increase stability, decrease conflict, and support local peace agreements under the auspices of the AU; ii. Coordinating the disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) of armed groups under AU auspices in coordination with the UN country team as needed. Specific activities include providing advice and logistical support to the AU for the DDR of armed groups in Darfur as well as helping to coordinate community arms collection. Peacekeeping Operation funds may also support the provision of technical support to monitor and implement ceasefire agreements; iii. Providing logistical support to AU-led Darfur consultations in centre-periphery security dialogue. Specific activities could include: 1) providing support to the AU (in coordination with UNAMID) on implementation of Darfur Peace Agreement security initiatives in the form of programs and workshops on these issues, and 2) providing technical advice to community leaders on security arrangements and other security issues, including training and workshops; iv. Supporting AU-negotiated security arrangements for IDPs and nomadic populations. In particular, funds may enhance traditional dispute resolution mechanisms by conducting training for local leaders. Funds may also enhance security arrangements for nomadic migration by coordinating security mechanisms developed by the AU and key stakeholders. No additional information on DSSI is currently available. Option 3: UK Bilateral contracting of NGOs/Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) to deliver to support community peace and stability Under this option the UK could seek to bilaterally contract NGOs and CSOs to deliver activities that support the first three critical success criteria: i) Effective community-level conflict resolution and prevention platforms in Darfur are in place, ii) Increased cooperation between communities over disputed livelihoods assets, income generating opportunities and access to natural resources, and iii) Equitable and sustainable growth promoted, with particular attention to ensuring that stabilised rural and urban areas remain stable. By way of estimating the number of contracted partners that would be required, DCPSF contracted 26 programmes, implemented by 13 NGOs and 3 UN organizations. It is expected that the larger investment justified in this business case would result in an increase in the number of programmes and implementing partners. In the table below: The quality of evidence for each option as is rated either Strong, Medium or Limited, The likely impact on climate change and environment is categorised as A, high potential risk / opportunity; B, medium / manageable potential risk / opportunity; C, low / no risk / opportunity; or D, core contribution to a multilateral organisation. Option Evidence rating Climate change and category (A, B, C, D) environment 1 Strong A 2 Limited - (not enough information to assess) 3 Medium - (not enough information to assess) Climate change and environmental impact of the proposed area of work and Option 1 (DCPSF) are assessed in detail at Flag C. A climate and environment assurance note is at Flag F. C. Appraisal of options A detailed social, political, institutional, economic, conflict and environment appraisal, against the three options, is attached at Flag C. Below is a summary. Costs, benefits and risks Option 1 – DCPSF: This option is assessed strongly in the detailed appraisals as the preferred option for UK funding. The economic appraisal concludes that “the very large economic impact of conflict on communities, as well as the cost of humanitarian support and peacekeeping operations mean that a successful peace-building effort (through DCPSF) stands to make a significant economic return”. The appraisal could provide only non-quantifiable benefits at this stage. The reason is that, although evidence from the first phase showed significant direct benefits from the programme1, these interventions are only instruments to help support local reconciliation efforts through empowering local leaders mediating disputes over assets. Therefore, much larger returns should be realised through the prevention of conflict and associated costs. The social appraisal concludes that, this option, and option 3 are equally preferable. The appraisal states that “Sustainable peace is a prerequisite for increased and sustainable livelihoods opportunities for all and especially for poor and marginalised communities in Darfur. The delivery of material inputs (programmes and services) that respond to community needs, whilst underpinning processes of dialogue and consultation outlined in this option has the potential to contribute to improved livelihoods and in the long term a reduction in poverty”. The political, conflict, institutional and environmental appraisals assess DCPSF / Option 1 as the preferred option. If this option is approved, the detailed appraisals cite the following requirements for implementation: - DFID Economic Adviser and the DCPSF Technical Secretariat complete the suggested steps, laid out in the economic appraisal, over the next six months, for a final cost-benefit analysis to be completed and for this to influence the project approach; - DCPSF Technical Secretariat minimises social risks by considering and monitoring equity of programme benefits in the geographical and social distribution amongst diverse livelihood communities; - DCPSF Technical Secretariat are tasked with regular analysis of the conflict dynamics and their impact on livelihoods, to ensure that resources are allocated according to changing needs and that the programme ‘does no harm’; - DCPSF Technical Secretariat are tasked to monitor and ensure that marginalised groups, including pastoralists, and women and the youth are involved in and benefit from peace-building activities and from material inputs; - DFID annual reviews check that the funding mechanism remains flexible enough to direct funding to newly accessible areas, or to re-direct funding, to areas that can be accessed, or to partners that are allowed to work; - DFID ensures that the UK maintains a comprehensive package of interventions designed to support a positive peace in Darfur (including financial and technical support for formal and Track 2 and 3 peace talks); 1 Provision of livelihood and other support, including 3326 people receiving training in agricultural extension, 18,736 livestock being vaccinated and 200,000 new seedlings planted - The DCPSF Technical Secretariat is tasked, in reviewing whether a ‘Reconciliation and Peaceful Coexistence Mechanism’ RPCM style at state-level reconciliation mechanism would be useful and feasible for Darfur, and if so, how such a mechanism could be established; - DFID and the DCPSF Steering Committee give priority to the proposed “market study on alternative management arrangements that will be conducted leading to a tender with a view to seek alternative more cost-efficient management arrangements”. Depending on the outcome of the tender, the management arrangements should be found either cost-effective, or new, cost effective arrangements put in place. - Programme management team ensure that UNDP develop a costed 4 year staffing plan with details of all the posts at the Technical Secretariat, contract start and end dates, recruitment timelines etc by end October 2011 - The need for proper water resource assessments before embarking on extensive infrastructure development: i. The Technical Secretariat should immediately be tasked with drafting a matrix of infrastructure that could be supported by the fund, which will be updated during quarterly reporting; ii. The steering committee should task the Technical Secretariat with ensuring there are environmental assessments of all new infrastructure that is supported (including location and vulnerability of new infrastructure to flooding and its potential to increase the adverse impact of floods). iii. The Technical Secretariat should develop standard procedures to ensure that the maximum amount of local materials are used for infrastructure development; iv. For water infrastructure, the Technical Secretariat should ensure that available groundwater resources have been assessed and a sustainable level of abstraction is understood (likely through other actors and projects – such as UNEP) before work starts (where necessary, Integrated Water Resource Management – IWRM – plans should be in place before water resources are developed; - As it is likely that more extreme environmental events are likely, establishing mechanisms to facilitate conflict resolution is critical, but the future programme reviews must assess the ability of such mechanisms to cope not just with existing climate variability but to future climate variability; - DFID to track the possible confirmation of oil in Darfur and if fields are confirmed and developed consider how it tackles this possible issue through this programme (community conflict resolution platforms) and additional work (e.g. through the extractive industries transparency initiative). - DFID to ensure selected analytical work is undertaken to provide more understanding of the context of the programme environment and to strengthen the impact of the of the programme, (e.g. a study on the economic impact of the programme (the balance of the cost and benefits) and a review of the capacity of civil society in Darfur and its role in peace building). Option 2 – DISSI: At this stage not enough is known about this option to provide a full social, institutional, environment or economic appraisal. From a political perspective this option is assessed as high risk. From a conflict perspective it is concluded that “this option should not receive funding unless significant additional information can be provided on the proposal, ensuring all critical success criteria are addressed in the approach”. Option 3 – Bilateral Contracting: At this stage not enough is known about this option to provide a full economic or environment appraisal. From a political and social perspective this option is seen as an acceptable alternative to option 1 but politically a higher risk, given that DFID is unlikely to be able to shift implementing partners and funds around as easily as the DCPSF project. The conflict appraisal concludes that “this option should not receive funding unless an additional implementing partner is contracted to assess and build capacity of the proposed partners and funding is set aside in the proposal to enable DFID to contract support for the collection of evidence of effective grassroots peace building and to help the UK feed this into wider peace forums”. The institutional appraisal also concludes that this option “should not receive funding unless an additional implementing partner is contracted to assess and build capacity of the proposed partners”. D. Comparison of options The same weighting is used as for CSCs above. The score ranges from 1-5, where 1 is low contribution and 5 is high contribution, based on the relative contribution to the success of the intervention. Analysis of options against Critical Success Criteria (CSC) Option 1 Option 2 Option 3 CSC Weight Score Weighted Score Weighted Score (1-5) Score (1-5) Score Weighted Score 1 5 4 20 2 10 3 15 2 5 4 20 1 5 3 15 3 3 4 12 1 3 3 9 4 2 4 8 0 0 0 0 Totals 60 18 30 With scores provided based on the analysis summarized above and provided in detail in Flag C, Option 2 scores 18, Option 3 30, and Option 1 60. Option 1 is therefore the preferred and recommended option. Assessment of gender sensitivity – As per the social appraisal in Flag C, Option 1 is assessed as strong on gender sensitivity, but clear recommendations for monitoring, improving and strengthening gender sensitivity are provided, and highlighted in the appraisal summary above. E. Measures to be used or developed to assess value for money – A detailed process has been established for the first 6 months of implementation, to ensure value for money can be adequately assessed and monitored. For full details see the economic appraisal at Flag C. Business Case for Reducing Conflict Between Darfur Communities in Sudan Commercial Case Indirect procurement A. Why is the proposed funding mechanism/form of arrangement the right one for this intervention, with this development partner? DFID will provide funds to the DCPSF programme through UNDP. The agreement format will be an MoU, falling under the standard umbrella agreement DFID already has with UNDP. This funding mechanism is in line with DFID guidelines. B. Value for money through procurement A DFID-funded review of the first phase of the DCPSF found that the mechanism of UNDP acting as managing and administrative agents was expensive, with a set fee rate making overheads high compared to the overall value of the fund and the grants being made from it. In working with the DCPSF Technical Secretariat on the terms of reference for the second phase of the programme we have pushed for greater options to achieve improved value for money. The terms of reference now include plans to tender for a managing agent during the second phase of the programme. This approach has the agreement of the Steering Committee, including DFID. It was agreed that this tender process would not be immediate in order not to cause a gap in programming. UNDP will be free to bid for the role but it is hoped that a transparent tendering process will help achieve improved value for money from which ever party is selected. In the meantime DFID will continue to monitor closely the value for money of UNDP’s management of the DCPSF funds. Business Case for Reducing Conflict between Darfur Communities in Sudan Financial Case A. How much it will cost Eight donors contributed a total of $33.5m to the DCPSF (phase 1) as follows: Denmark $ 942 thousand, Germany $ 513 thousand, Italy $ 2,557,800 million, Netherlands $15,500 million, Norway $ 2,548 million, Sweden $2,832 million, Switzerland $300 thousand and UK $ 8,332 million. The overall project budget for the DCPSF (phase 2) is a minimum of $40 million (approx. £24.2 million) out of which other donors have made soft pledges in this financial year 2011/12 totalling about $9 million. DFID is proposing to provide up to £8.5 million which is available in the current DFID Sudan framework and included in DFID Sudan BAR offer. The project budget is broken down as follows: 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 Total £1.6m £1.6m £1.6m £1.6m £6.4m Out of the £6.4 million a 6.2 million will be disbursed directly to the DCPSF (phase 2) programme while a £200,000 will be allocated by DFID to conduct analytical work to provide more understanding of the context of the programme environment and to strengthen the impact of the programme. That amount is included in the budget breakdown above. The balance of £2.1 million will not be programmed immediately but will allow for DFID to respond to a cost and/or time extension to the programme. B. How it will be funded: capital/programme/admin This intervention will be wholly programme funded. The programme budget will contribute to the different components as follows: 1. the direct disbursed DFID’s contribution to the DCPSF (phase 2) (£6.2 million) is distributed, as follows: Grants Technical secretariat 73% 5% Administration agent 20% Monitoring and Evaluation (lessons-learned and impact evaluation exercises in the entry of DCPSF (phase 2) dates to be confirmed and mid term review by July 2013) Total £4,520,000.00 £320,000.00 £1,240,000.00 2% 100% £120,000.00 £6,200,000.00 2. Analytical researches and studies (out of the direct disbursement to DCPSF (phase 2) up to £200,000 C. How funds will be paid out An MoU will be signed with UNDP. As UNDP will require the funds in order to place calls for proposals, funds will be paid out in six monthly advances of approximately 50% of each annual financial allocation. Funds may be paid out more frequently than six monthly where UNDP can provide evidence that previous funds have been wholly utilised. In the event that a private sector company takes over the role of managing agent they will be contracted to the UN and not DFID. D. How expenditure will be monitored, reported, and accounted for DFID will actively participate in the DCPSF steering committee. Participation in the committee will allow us a say in how funds are allocated and to participate in field monitoring visits. Both the managing agent and the technical secretariat will perform monitoring and evaluation roles and report to the steering committee. Consolidated financial statements will be provided by UNDP as managing agent on a quarterly basis, showing income and spend across the fund. Any assets procured for the fund will be paid for by multiple donors. At the end of the programme DFID will agree, in conjunction with the other donors and the DCPSF Technical Secretariat the best course for disposal. Any disposal will take account of DFID guidance on assets. Business Case for Reducing Conflict between Darfur Communities in Sudan Management Case A. Oversight The DCPSF governance structures have been set up in line with agreed Multi Donor Trust Fund (MDTF) architecture. The DCPSF is to be overseen by a governing Steering Committee (SC), under the chairmanship of the Resident Coordinator / Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC), with representatives of each donor, an appointed INGO representative and an appointed UN agency representative. The SC will be responsible for mobilising resources, providing strategic guidance, commissioning independent evaluations and reviewing progress, amongst other responsibilities. The SC will have a four voting member decision-making body (the RC/HC Chair, an appointed donor representative, an appointed INGO representative, a UN agency) for decisions on proposals for DCPSF funding and on DCPSF project extensions. In addition, a Technical Secretariat (TS) has been established to oversee the preparation and decision-making processes related to the DCPSF. Other important stakeholders, including the Joint Mediation Support Team (JMST), World Bank and the Darfur Darfur Dialogue and Consultation, are invited to the SC as observers. Beneficiaries will be represented through the implementing agent representatives (INGO and UN), on the SC. This structure ensures that all major stakeholders are directly represented. UNDP will provide the administrative and legal architecture for the DCPSF, in its dual role of Administrative Agent (AA) and that representing Participating UN Organisations as Managing Agent (MA). As per the structures outlined above, this ensures that the managing agent is accountable to the oversight body (SC) and SC decisions will be binding to the MA. The performance of the project will be assessed through a Mid Term Review to be commissioned by July 2013 and an independent ‘lessons-learned and (impact) evaluation exercise’, to be commissioned by the SC in the final year of the fund. Note: more information is at Flag B – the DCPSF Terms of Reference. B. Management The core governance structures have been outlined above. These are represented in the following chart: FIGURE (1): DCPSF GOVERNANCE ARRANGEMENTS DCPSF Steering Committee (SC) Recommended proposals for approval to SC Technical appraisal DCPSF Technical Secretariat (TS) Fieldbased appraisal Proposals in response to CfPs by TS Participating UN agencies and IOM Contribution to the DCPSF SC approval and instruction to AA to disburse funds Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) DCPSF Administrative Agent (AA) Funds disbursed UNDP Funds disbursed Managing Agent (MA) UNDP Participating UN agencies and IOM Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) Following the findings and recommendations of the DCPSF (phase 1) Mid-Term Review, in 20010, at the start of this phase, in 2011, the Steering Committee will commission a study to corroborate the most cost efficient management arrangements, while taking into account the Darfur specific working environment. Recommendations of the study will be submitted to the SC for consideration by early 2012. For DFID the fund will be managed by the Humanitarian and Conflict team Programme Officer. Advisory oversight will be provided by the DFID Sudan Conflict Adviser supported by the DFID Sudan Governance Adviser, as lead, with cross-cutting support from the DFID Sudan Social Development and Economic Advisers. DFID programme staff and advisers will draw on internal expertise where possible, including relevant Stabilisation Unit, Policy Division and Africa Regional Department staff. Through the agreed mid-term review and regular quarterly reporting, annual reporting and annual DFID review, all based on a very strong, agreed results-framework (logframe), there is a clear process to measure results-based delivery. DFID’s project performance is laid out in the deliverables of the agreed results-framework. If the fund did not achieve the expected results or fail to represent good value for money and / or clear and timely measures have not been put in place to improve performance, DFID will then discuss the option whether to suspend its funds. Note: more information is at Flag B – the DCPSF Terms of Reference. C. Conditionality Not applicable. D. Monitoring and Evaluation The DCPSF has a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation strategy designed to: i) Gain an improved understanding of the DCPSF funded projects, the conflict sensitivity and the conflict context in which it is being implemented; ii) Assess operational progress towards achieving outputs; iii) Factor in lessons learned programming/allocation decisions; iv) Measure the impact of DCPSF on stabilising Darfur. from ongoing initiatives into future The DCPSF has the following tools to deliver against these objectives: i) A detailed results framework to enable the project to measure progress against milestones, targets and outputs. Monitoring data will be gathered from a range of sources, as outlined in the results framework; ii) Each sub-project that receives funding from the DCPSF mechanisms will provide i) quarterly updates on progress; ii) annual narrative progress reports and iii) final narrative progress reports; iii) Desk monitoring by a technical secretariat; iv) Regular DCPSF partner meetings to ensure a forum open for debate and exchange of information, ideas and lessons learned; v) Field monitoring to enable first-hand observation of the project environment and setting; vi) The DCPSF will provide i) consolidated six-monthly progress updates; ii) consolidated annual narrative progress reports; and iii) consolidated final narrative progress reports; vii) Finally a Mid Term Review will be commissioned by July 2013 and an independent ‘lessons-learned and (impact) evaluation exercise’, will be commissioned by the SC in the final year of the fund. In addition project progress will be regularly monitored against expenditure and the DFID logical framework through the DFID annual review process. The independent evaluation cited above will feed into DFID’s Project Completion Report (PCR) which will be arranged by DFID staff. Note: more information is at Flag B – the DCPSF Terms of Reference. E. Risk Assessment The key risks that threaten the successful delivery of this fund are below. Mitigating actions for each risk are detailed Risk Likelihood Impact Mitigation Strategies Broader conflict spoilers Medium interfere in the processes necessary to restore trust and confidence at community level High - Broader UK and international support to the Darfur Peace Process; New or reformed Low conflict resolution platforms fail because of lose of credibility after being established due to inability to meet expectation. Low - Improved quality of peace building training and increase in funding available for conflict resolution platforms to implement conflictmitigation activities ensuring such platforms are more able to meet expectations. Conflict is not resolved Medium because vulnerable groups, such as women, youth and the poor are not effectively included and unable to voice their concerns. Medium - Improved monitoring of ‘inclusion’ by DCPSF implementing agents and UN; Limited absorption Medium capacity and availability of adequate implementing partners in Darfur High - DCPSF Projects work to increase inter-community dialogue specifically focusing on mitigating risks of spoilers and establishment of early warning mechanisms. - Improved protocols for sub-projects to ensure ‘inclusion’ in design and implementation; - Cross-cutting inputs of DFID Sudan Social development Advisor. - Increased focus on capacity building of implementing agents through tailored training and support for partnerships between International NGO and National NGOs; - Provide more time for applicants to design proposals in reply to DCPSF Calls for Proposals. Access to project sites is Medium impossible due to unstable and unpredictable security situation in the three Darfur States, continued presence of armed groups; prolonged rainy season, road closures and inaccessibility; safety of staff travelling by road and otherwise High - Implementing through the UN platform, enables access to UN security (UNDSS) who offer supporting, including armed escorts, that enables greater activity; - If necessary, suspend DCPSF projects until security on the ground permits quality service delivery; - Implementing partners supported to factor environmental risks into their action plans; - increase delegation of M&E functions to local partners, and technical support for national partners to improve their understanding of M&E, reducing reliance on externals who may not be able to access project sites. Implementing partners Low become targets of violence because of collaboration with UN or because of unclear or inadequate engagement with authorities Medium - DCPSF TS transparently engages with government on purpose and activities of the Fund, and seeks high-level UN support where/when needed; - Reduce exposure through lowprofile approach in sensitive areas; - Develop and effect a clear, open and continuous communication strategy and manage expectations, pre-empt open communication with key-stakeholders and the wider public. The project is not implemented to time High Medium due to organisational and programme management being challenged by slow recruitment and the overall regulatory and operational environment. - Senior-level UN engages with UNDP HR with a view to prioritise staffing; - UNDP to develop a costed 4 year staffing plan with details of all the posts at the TS, contract start and end dates, recruitment timelines etc by end October 2011 -Senior-level UN timely engagement with relevant government bodies for expedient issuance of visas and stay permits. Project does not meet funding target of $40m. High Medium _-TS to monitor spend of project and provide biannual reports to SC ahead of disbursement of each funding tranch. - DFID to meet quarterly with the TS to monitor spending and ensure delivery of key results. - TS to develop a prioritisation mechanism to ensure proposals for funding match the available funds to avoid overspending. DFID Sudan believes that the most significant risk is that broader conflict spoilers interfere in the processes necessary to restore trust and confidence at community level. Based on evidence and experience from the first phase, DFID Sudan believes that benefits of increasing stability/reducing conflict in this case, outweigh the risks and is willing to go ahead with this programme. Residual risk is low. Major risks and mitigating actions are identified above. More information is at Flag B – the DCPSF Terms of Reference. The risks that UK funds are not used for their intended purposes are low. The multi-donor trust fund model has strong processes in place to ensure funds are fully accounted and audited. The risk that the fund does not deliver the expected results is mitigated through the monitoring and evaluation methodology as laid out in sections B and D above. In case the fund overachieves, it is recommended that the UK submit for additional funding, above the initial amount to be provided to the fund, so additional support can be easily provided. F. Results and Benefits Management DFID has a detailed and strong logframe, based on the DCPSF results framework. This framework will provide evidence of progress against realistic milestones, targets and outputs, including under or over achievement. The logframe is a results-based version of the theory of change required for this intervention, and outlined in the situational analysis above. i MENARG paper, Darfur in 2011: The elusive peace Buchanan-Smith, M. et al (2011) City limits: urbanisation and vulnerability in Sudan. Nyala case Study. London: HPG ODI; Young, H. et al (2009) Livelihoods, power and choice: The vulnerability of the Northern Rizaygat, Darfur, Sudan. Medford: Feinstein International Center, Tufts University; Buchanan-Smith, M. et al (2008) Adaptation and devastation: the impact of the conflict on trade and markets in Darfur. Medford: Feinstein International Center, Tufts University; Jaspars, S. et al (2010) Coping and change in protracted conflict: the role of community groups and local institutions in addressing food insecurity and threats to livelihoods. A case study based on the experience of Practical Action in North Darfur. London: HPG ODI; Young, H. (2011) Navigating Without a Compass: The Erosion of Humanitarianism in Darfur. Medford: Feinstein International Center, Tufts University. Martinez – Darfur Intervention Review for DFID, 2010 Darfur : The Quest for Peace, Justice and Reconciliation; Report of the African Union High Level Panel on Darfur (AUPD) October 2009 Darfur : Towards a new strategy for achieving comprehensive peace, security and development September 2010 OECD DAC Guidelines on Conflict, Peace and Development Co-operation Report on the Review of the DCPSF March 2010 Traditional Justice in Darfur July 2010 DfID paper Brickhill, J., 2007, 'Protecting Civilians Through Peace Agreements - Challenges and Lessons of the Darfur Peace Agreement' OECD DAC Guidelines on Conflict, Peace and Development Co-operation DCPSF Annual progress reports Darfur: The Quest for Peace, Justice and Reconciliation; Report of the African Union High Level Panel on Darfur (AUPD) October 2009 GoS Darfur Strategy Albany Associates, ‘Assessing Attitudes and Public Opinion in Darfur’, 2010 Heidelberg Group, ‘Darfur Dialogue Outcomes’, 2010 USAID , ‘Darfur: Changing Dynamics at the Local Level’, 2010 UN-RCSO, ‘Beyond Emergency Relief in Darfur’, September 2010 UN-RCSO, ‘Darfur Humanitarian Profile Narrative’ 2009 UN-RCSO, ‘Darfur Aid Sustainability’, 2010 UNDP Sudan, ‘Brief on Budgets and Aid in Darfur’, 2010 UNDP Sudan, ‘Darfur Fact Sheet’, 2010 UNDP Narrative 2011 Regional Workplan – Darfur DCPSF Implementing Partners’ Progress Reports DFID, Report on the Review of the DCPSF March 2010 World Bank, Breaking the Conflict Trap, Policy Research Report, 2003 DFID, Working effectively in Conflict-affected and Fragile Situations, a DfID practice paper, 2010 DFID, Urbanisation in Darfur September 2010 DFID, Traditional Justice in Darfur July 2010