Invasive Species Articles

advertisement

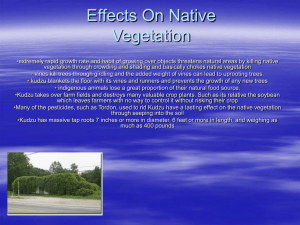

Asian Tiger Mosquito Aedes albopictus How did it get here? The Asian tiger mosquito hitched a ride to the United States in used tires imported from Japan or Taiwan. It was first discovered in the continental United States in 1985 in Houston, Texas. The insect is native to New Guinea and the islands in the Indian Ocean, ranging westward to Madagascar, northward through India and Pakistan, and through China to Korea and northern Japan. How to spot Aedes albopictus has striking black-and-white checkered legs and a white “racing stripe" that runs down the top of its thorax. Its abdomen has an incomplete, white stripe that appears as a series of bold, white dots. If you receive a bite early in the morning or late afternoon (after sunrise and before dusk), the culprit is most likely the Asian tiger mosquito. Unlike other mosquitoes, it is active and feeds during the day (diurnal), with the females seeking blood meals from warm-blooded animals, especially people. Your breathing gives you away: Female mosquitos hunt by homing in on carbon dioxide, a byproduct of respiration in mammals. Habitat characteristics Mosquitoes live and reproduce near shallow, standing water. They breed in "containers"—including artificial ones like tires, bottles, and leaf-clogged gutters, or natural ones such as holes in rocks or trees. Mosquitoes need only ¼inch of water to complete their life cycle. Life Cycle Male and female mosquitoes sip flower nectar for their own sustenance, but the mated female must obtain a blood meal for protein to nourish egg development. The female extracts blood from a mammal or bird using its elongated proboscis. She then deposits 40 to 150 eggs along the sides of a container, just above the surface of the water. The cycle of blood meals and egg-laying continues weekly throughout the adult's lifespan, which ranges from a few days to a few weeks. Eggs can overwinter in water or near water, hatching when the temperature warms. Larvae feed on debris in the water for five to 10 days, transforming into aquatic, non-feeding pupa for about two days. Winged adults emerge from the pupa and mate. Asian tiger mosquitoes do not fly far from their breeding sites, but their range is appreciably expanded when humans inadvertently transport their eggs or larvae in water. The international trade in used tires fueled the mosquito's spread over wideranging areas, but eggs or larvae can travel in any container. The species moved across Florida from graveyard to graveyard in flower vases as well as tires and other containers. Seehttp://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/current.html#Mosquito. Look-alikes and how to distinguish Aedes albopictus resembles other species of mosquitoes, but its white stripes make it virtually unmistakable. Why is this animal a problem? Mosquitoes acquire diseases from a host animal when the female sucks the host’s blood. The mosquito transfers the disease to another animal during a later feeding. In the United States, the Asian tiger mosquito may spread diseases such as West Nile virus and encephalitis. The Centers for Disease Control keeps a close watch on this species because of its great potential as a diseasevector in the United States. For information on all of the diseases potentially carried by the mosquito, seewww.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/arbor/albopic_new.htm. Besides spreading disease, this mosquito inflicts pain on humans. Its bite is no worse than other mosquitoes, but the numbers of adults can be so high that it is difficult to work or play in infested areas. Kudzu Pueraria lobata How did it get here? Native to Japan, kudzu was brought to the United States in 1876 for the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, where it was promoted as an ornamental plant for gardens and food for goats, cows, and pigs. To control erosion, it was planted in the South from 1935 through the mid1950s. The United States Department of Agriculture removed kudzu from its list of recommended ground cover plants in 1953, when it became recognized as an aggressive nuisance. The agency listed kudzu as a noxious weed in 1972. Infestations are particularly heavy in the Deep South, and in Florida it is invading the Everglades. How to spot Kudzu is a vine that can grow very long—from 32 to 100 feet. A kudzu patch looks like a uniformly colored blanket of dark-green leaves, swallowing everything in its path both horizontally and vertically. The leaves, grouped in threes, are 3 to 10 inches long and can have as many as threelobes. They have hairy undersides. Depending on the climate and sun exposure, kudzu may flower from late July to September. It bears hanging clusters of purple blossoms that smell like grapes. Seedpods, which appear later, are hairy and bean-like. In winter or after a hard frost, kudzu is a mass of brown vines with leaves withered or absent. In very warm areas, leaves may be evergreen. Habitat characteristics Disturbed areas, including roadsides, abandoned yards, fields, forest edges, and vacant lots. Deep, well-drained, loamy soil. Grows best in climates with mild winters, hot summers above 80 degrees F, and abundant rainfall, but can withstand harsher weather. Life cycle Kudzu is in the legume family. It spreads vegetatively and, to a much lesser extent, from seed borne in pods. In summer, kudzu can grow as much as 1 foot per day. As many as 30 vines may grow from the root crown, andrunners sprout from nodes every 1 to 2 feet along the vines. With enough sun, kudzu may flower from late July to September, after which seedpods form. It may die back to its roots during cold winters. Look-alikes and how to distinguish Large specimens of poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans)—lack obviously hairy leaves and stems. Crown vetch (Securigera varia)—leaves are finer with 15 to 20 leaflets per leaf; profuse pink flowers. Round-leafed beggar’s tick (Desmodium rotundifolium)—rarely exceeds 5 feet in length; leaflets not usually longer than 2¾ inches. Why is this plant a problem? Kudzu kills native plants by smothering them and blocking their sunlight. Climbing vines can girdle trees, and their weight can uproot trees. Loss of trees and plants to kudzu threatens agricultural and timber production. German Cockroach Blatella germanica How did it get here? The German cockroach is actually a tropical species whose point of origin may be Southeast Asia. It spread to America aboard the ships of European immigrants sailing to the Colonies. Highly mobile and adaptable to new environments, the species became a household pest worldwide during the 19th century. How to spot German cockroaches are nocturnal and secretive. They spend most of their time in cracks or crevices in walls, between cabinets, and under furniture. Signs of cockroaches include carcasses, body parts, shed skins, empty egg cases (amber-colored, ribbed cylinders) and fecal smears (dark smudges). Habitat characteristics Cockroaches live where humans dwell. They prefer warm, undisturbed areas with high humidity near a source of water—under sinks, around toilets, and in showers. They eat human food and also non-food items like soap, toothpaste, and glue. Small nymphs can live in a crack as small as 1/32 inch, while adults require one at least 3/16 inch wide. Life Cycle Females produce four to eight egg cases, each containing 30 to 40 eggs. They carry the cases until the eggs are within a day or two of hatching, then deposit the cases in a protected site. The development from egg to adult varies with temperature and humidity, but on average it takes 103 days. Three to six generations may be produced per year. Adults can live 100 to 200 days. Look-alikes and how to distinguish • American cockroach (seehttp://pested.unl.edu/chapter3.htm#cock3e) • Brown-banded cockroach (seehttp://pested.unl.edu/chapter3.htm#cock3c) • Oriental cockroach (seehttp://pested.unl.edu/chapter3.htm#cock3d) • Wood cockroach (seehttp://pested.unl.edu/chapter3.htm#cock3f) Why is this animal a problem? German cockroaches contaminate food with their droppings. They can transmit bacterial diseases to humans that can cause food poisoning, dysentery, or diarrhea. Many people are allergic to cockroaches, their waste, or their body fragments, and such allergies cause asthma in some children. Cockroaches can damage household items, eating glue in wallpaper, books, and furniture. Japanese Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica Thunberg) How did it get here? Native to eastern Asia, Japanese honeysuckle was brought to Long Island, N.Y., as an ornamental in 1806. A more aggressive variety was imported to Flushing, N.Y., in 1862. Initially slow to escape cultivation, this vine was established from Connecticut to Florida by 1918. It is now considered naturalized throughout the eastern and central United States. It has also invaded Hong Kong, England, Wales, Portugal, Corsica, Hawaii, Brazil, and Argentina. How to spot Lonicera japonica is a trailing or twining woody vine that is evergreen in most of North Carolina. Vines can reach 30 feet in length. Leaves alternate along the stem and are ovate (young ones may be lobed) and about 1 1/2 to 3 inches long. Young plants have hairy stems while older ones have smooth, peeling bark. Very fragrant white flowers that fade to yellow are borne in pairs from April through June. Seeds are black berries, produced August through October. Habitat characteristics • Sun to partial shade. • Grows most vigorously on rich, moist soil, but is drought-tolerant. • Common in disturbed areas such as roadsides, trails, fencerows, and abandoned fields. Life Cycle Honeysuckle reproduces by seeds, underground rhizomes, and aboveground runners. Look-alikes and how to distinguish • Coral or trumpet honeysuckle (L. sempervirens L.)—leaves joined together around stem (connate); red/orange berries; scarlet red flowers. • Wild or limber honeysuckle* (L. dioica L.)—leaves joined together around the stem (connate); red/orange berries; pale yellow, orange, or purplish flowers. • Yellow honeysuckle** (L. flava)–red/orange berries; yellowish to pale-orange flowers. * rare in North Carolina mountains, endangered in Illinois, Kentucky and Maine, and of special concern in Tennessee. ** rare and local in North Carolina Mountains, endangered in Illinois, of special concern in Tennessee, and extirpated in Ohio. Why is this plant a problem? Japanese honeysuckle invades native plant communities following natural or human-induced disturbances such as floods, ice and windstorms; the building of logging roads; or outbreaks of disease. It grows densely both vertically and horizontally, smothering and shading out native plants and depleting the soil of moisture and nutrients. It disfigures the trunks of trees and topples upright vegetation under the weight of its vines. It can bring down a 13-foot tree in the span of a summer. English Ivy Hedera helix How did it get here? English Ivy’s native range is Europe, western Asia, and northern Africa. It was probably introduced to North America from Europe in Colonial times. It is sold widely throughout the United States as a landscaping plant. How to spot English ivy is a climbing, evergreen vine. The vines attach to the bark of trees or other surfaces with small rootlets that older plants, vines Because of its horticulturists have ivy. The most common form leaves that grow typically have three exude a glue-like substance. In may grow to 1 foot in diameter. popularity as a ground cover, developed many varieties of English has dark-green, waxy, leathery alternately along the stem. Leaves lobes and a heart-shaped base. Habitat characteristics Prefers shade but can grow in part sun. Moist, but not extremely wet, soil. Woodlands, forest edges, fields, hedgerows, coastal areas, and edges of salt marshes. Invades areas after natural or human-induced disturbances and frequently escapes its boundaries in landscaping. Life Cycle English ivy reproduces by seed and vegetatively. New plants grow when stems make contact with the soil. With enough sunlight, the plant produces clusters of small, greenishwhite, five-part flowers in the fall. The ¼-inch black berries that form afterward contain hard, stone-like seeds. The fruits ripen during winter, and seeds mature by spring. The fruits contain toxic glycosides that make some birds vomit, disseminating the seeds. Look-alikes and how to distinguish Boston ivy or Japanese ivy (Parthenocissus tricuspidata)—deciduous; serrated, three-lobed leaves. Why is this plant a problem? English ivy aggressively spreads across the ground, forming a dense blanket that shades and kills native plants. It also climbs up trunks and intotrees, preventing sunlight from reaching the trees’ leaves. The weight of the vines makes a tree more likely to be toppled by storms. English ivy also hosts bacterial leaf scorch (Xyella fastidiosa), a plant pathogen that spreads to native elms, oaks, and maples. Japanese Stilt Grass Microstegium vimineum How did it get here? First identified in Knoxville, Tennessee in 1919, this grass may have been introduced accidentally through its use as a packing material for Chinese porcelain. Its native range is Japan, Korea, China, Malaysia, and India. Japanese stilt grass was found in western North Carolina in 1933. How to spot Microstegium vimineum grows in a sprawling pattern and may form colonies to 3 feet in height. It has a branched stalk withalternate leaves that are thin, pale green, lance-shaped, and about 3 inches long. The leaves have a silvery strip of reflective hairs in the center of the upper surface. Delicate spikes of flowers appear near the tips of the stalks in late summer and early fall. Habitat characteristics Moderate to dense shade. Moist, nitrogen-rich soils with acidic to neutral pH. Naturally or artificially disturbed sites such as roadsides, ditches, woodland borders, floodplains, and streamsides. Selectively colonizes bare ground not occupied by other plants. Life cycle Japanese stilt grass is an annualthat reproduces from seed. The grass grows in colonies, rooting from the nodes and sometimes forming dense stands of the same plant. Each plant produces as many as 1,000 seeds that remain viable in the soil for at least five years. Seeds are dispersed naturally by wind and water (streams and ditches) and are transported by humans in hay and soil. Look-alikes and how to distinguish Cutgrass (Leersia virginica)—longer leaves. Knotweed (Polygonum persicaria)—pale to dark-pinkcalyx and glossy, brown nutlets. Why is this plant a problem? Although it is generally slow to colonize undisturbed areas, Japanese stilt grass can rapidly fill disturbed areas such as streamsides scoured by flooding and sewer line rights-of-way that are mown annually. The dense stands that it forms can crowd out native vegetation in just a few years. Once these stands are established, the natural soil conditions such as pH and organic composition begin to change, potentially preventing the re-establishment of the original native species. Deer do not eat Japanese stilt grass, giving the plant an advantage in heavily grazed locations.