Associate Professor Beth Kotzé (Word 17 KB)

advertisement

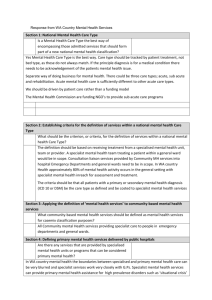

1 Response to the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority (IHPA) Consultation Paper for the Definition and Cost Drivers for Mental Health Services Project Associate Professor Beth Kotzé, Member: Inpatient/Hospital Based Services Expert Working Group, MHSPF Question 1: Is a Mental Health Care Type the best way of encompassing those admitted services that should form part of a new national mental health classification? Yes Question 2: What should be the criterion, or criteria, for the definition of services within a national Mental Health Care Type? Mental health care is commonly provided in non-MH-designated settings, for example, Emergency Departments, Paediatric wards, general hospital and maternity settings. From a policy perspective in relation to Child and Adolescent MH (CAMHS), early review and treatment planning in the Emergency Department, collaborative care and assertive in-reach in Paediatric settings, and collaborative care and consultation-liaison in maternity settings is actively promoted. For some disorders, for example, Eating Disorders or Conversion Disorders (in children), admission to a Paediatric setting may be favoured as developmentally and therapeutically indicated rather than admission to a specialist mental health unit. It should be noted that significant amounts of specialist mental health work may be associated with an outcome of ‘no mental health diagnosis’. It is not uncommon for all/many types of behavioural disturbance or difficult behaviour to be attributed to a mental health diagnosis, however specialist mental health examination leads to a conclusion that there is no mental health diagnosis. With children and adolescents, having confirmed there is no mental health diagnosis, the specialist mental health clinician/service may still have a role in the identification of child protection and/or family issues that require further referral and liaison with other services. Particularly in Emergency Department settings, this work will be completed by the MH clinician. Another example would be where clinicians seek specialist mental health clinical input because of difficult interactions with the parent/carer of a child, perhaps around issues of consent to provide medical/surgical treatment for the child. Hence it is recommended that the Mental Health Care Type should encompass treatment in a specialised mental health unit or by a specialised mental health program when the person has a principal diagnosis of another disorder/is more appropriately treated in another setting. This is consistent with the proposition (last paragraph page 8) that admission to ‘non-specialised’ mental health units could include ‘specialised mental health care days’. 2 However ensuring that the particular work of consultation-liaison mental health services is adequately reflected requires recognition of ‘assessment +/intervention by specialist mental health service/clinician but outcome no mental health diagnosis’. Question 3: What community-based mental health services should be defined as mental health services for casemix classification purposes? The following services should be included for CAMHS: - - Specialist community-based CAMHS; within this, assertive outreach models are inherently more expensive than clinic-based services; Daypatient programs - are a common model in CAMHS for emotionally and behaviourally disturbed children and adolescents, generally with a focus on school and community re-integration. Some are co-located with schools. Also for children and adolescents with Eating Disorders; ‘Partnership’ services: School Link (early identification and referral to specialist CAMHS of children in education settings); Out of Home Care MH programs/services; and other ‘complex care coordination’ services (for example, Juvenile Court Diversion, Whole of Family Teams where joint drug and alcohol and mental health services are provided to whole families as the unit requiring intervention); ‘wraparound’ models of intervention where participating agencies, including mental health ‘wrap’ suites of interventions around families. Question 4: Are there any services that are provided by specialised mental health units or programs that can be considered primary mental health? There is significant local variation in the roles of co-located public mental health services and headspace. General and specialist parenting programs require delineation. General parenting programs are still provided by some CAMHS – however the general trend is that this primary mental health type work is not being undertaken by specialist CAMHS. Specialist parenting programs, for example, those targeting parents with psychosis (for example, Poppy Play Groups) or personality disorder are either provided by specialist mental health services alone or in partnership with non-government organisations. Similarly there is a range of Children of Parents with Mental Illness (COPMI) programs that are best provided within the primary care sector. Nevertheless there is a component of specialist/more complex work that is required to be undertaken in the specialist mental health sector. School counsellors would legitimately fit with the definition of primary mental health care provided by Victoria (page 12 of the Consultation Paper). 3 Question 5: Should the mental health classification include alcohol and drugrelated disorders? If so, is it the diagnosis or specialised treatment setting that is used as the decisive criterion for inclusion in the definition? The mental health classification should not include alcohol and drug-related disorders. Question 8: Should mental health care in the Emergency Department (ED) be defined as ED or MH for classification purposes? If mental health encompasses emergency department care services, how should these services be classified? Mental health care in the ED should be defined as MH for classification purposes, consistent with the increasing trends for dedicated MH clinicians/services collocated/based within EDs and the significant MH work involved. In terms of classification, consideration needs to be given to the point raised earlier: a great deal of mental health work in the ED setting may result in a conclusion of ‘no mental health diagnosis’. Phase of care/change of care type would most likely be contentious and not as relevant as the emphasis shifts from ‘medical clearance/handover’ to proactive models of MH assessment and care planning in parallel with medical interventions. Question 9: Are there other examples of care models or pathways that are broadly similar, but are classified differently by jurisdictions in the mental health patient-level NMDSs? Early Intervention in Psychosis services and perinatal mental health services would be additional examples. For child and adolescent mental health, many services are delivered in the absence of the identified patient – for example, school and parent based interventions for Conduct Disorders of all levels of severity; complex care co-ordination involving multiple agencies and wrap-around services. Or the identified patient in the traditional child-centred family focussed model is not the focus - for example Whole Family Teams which provide comprehensive assessment and treatment to the individuals and the family as a whole and outcomes include measures of family functioning rather than just individual outcomes for a specific individual.