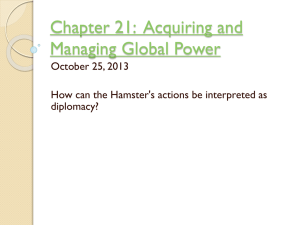

Puerto Rican Debt Crisis Options Brief – Full Intro

advertisement

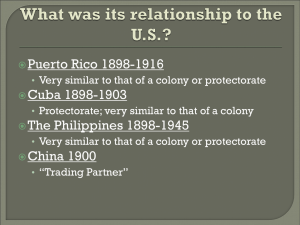

OPTIONS MEMORANDUM ON THE PUERTO RICAN DEBT CRISIS TO: FROM: SUBJECT: DATE: CC: Alejandro Jacier García Padilla, Governor Commonwealth of Puerto Rico Barack Obama, President of the United States of America Eduardo Bhatia Gautier, President of the Senate, Puerto Rican Senate Joseph Biden, Vice President of the United States, President of the U.S. Senate Orrin Hatch, President Pro Tempore, United States Senate Mitch McConnell, Majority Leader, United States Senate Harry Reid, Minority Leader, United States Senate Jaime Perelló, Speaker of the House, Puerto Rican House of Representatives Carlos Méndez Núñez, Majority Leader, Puerto Rican House of Representatives Jennifer Gonzàlez, Minority Leader, Puerto Rican House of Representatives John Boehner, Speaker of the House, United States House of Representatives Kevin McCarthy, Majority Leader, United States House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi, Minority Leader, United States House of Representatives Jonathan Lee Gibson Tara Gitter Options Regarding the Puerto Rican Debt Debt Crisis September 13, 2015 Melba Acosta Febo, Secretary of Treasury of Puerto Rico Jack Law, Secretary of the Treasury of the United States of America Janet Yellen, Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve THE PROBLEM The fiscal crisis that is facing the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico is potentially grave. With a public debt obligation exceeding that of most states, and tax revenues dropping, (14.1% in May 2015, year over year1) the long term viability of the Commonwealth’s ability to meet its financial obligations is bleak as has been further evidenced by recent credit downgrading’s by Moody’s2 to “Caa” and Standard & Poor’s3,4 from “B” to “CCC-plus” to “CCC-minus” of the Commonwealth’s sovereign debt. While some claim that the reason for the Commonwealth’s fiscal crisis is due to a large welfare state 5 , 6 , 7 this reality only partially addresses the contributory factors of the Commonwealth’s recent fiscal decline and instability. Specifically, in addition to a bloated welfare state, corruption in the government has been high for years, with politicians giving public monies to the people for popular support. Further, emigration of the Commonwealth’s populous to the states has been increasing8 in recent years due to a lack of good jobs, substantially lowering tax income for the Commonwealth, which is only worsened by large underground economic sectors.9 These do not pay corporate, Gibson & Gitter: Puerto Rican Debt Crisis Options Memorandum Page: 2 individual or other payroll taxes to the Commonwealth. Finally, the trade policy instituted by the United States Federal Government, which prevents the Commonwealth from exporting and engaging in free trade without first exporting to the United States, has severe implications for the viability of industrial and agricultural sectors on the island. The issues the Commonwealth faces are not simply that of a bloated welfare state, but the confluence of many policies both local to the island and imposed on the island by the United States Federal Government. While it may be a temporary salve to the economic pains the island is facing it is not likely that simply having access to Chapter 9 municipal bankruptcy will ameliorate the current fiscal crisis. The problem is not just the totality of the debt load the Commonwealth is facing but also structural inefficiencies caused by the Commonwealth and Federal Government’s policies over the past few decades such as: not having access to Chapter 9 Municipal Bankruptcy, political corruption, loss of economic incentives and other structural issues which will be discussed. A review of each of these issues will help to frame the interconnectedness of the various problems contributing to the Commonwealth’s economic problems and hopefully elucidate a variety of policy changes that may help to attenuate these troubles. COMMONWEALTH STATUS AND THE STATEHOOD QUESTION Puerto Rico became a territory of the United States at the end of the Spanish-American War when Spain ceded Puerto Rico (and other colonies) to the United States. The Commonwealth’s relationship with the Federal Government has been wrought with difficulties ever since. For years, and as a result of the so-called “insular cases” of 1901, the people of Puerto Rico were denied United States citizenship. However, due to a need for military conscripts during the First World War Congress passed the Jones Act of 1917, which gave the people of Puerto Rico citizenship, but not equal rights of citizenship.10 However, Puerto Rico was still not allowed to self-govern and instead had a resident governor appointed by the United States Congress. It was not until 1947 that the United States Congress allowed the island to begin to incorporate as a Commonwealth and to elect its own governor. Even still it was not until 1950 when the United States Congress allowed the Commonwealth to draft its own local constitution, which was approved in 1952 by constitutional convention. To this day, the Commonwealth status and its relationship with the United States prevent it from having autonomy. The Island is still under the direct purview of the United States Congress, can not enter into free trade independent of the United States Congress, still does not have voting representation in Congress, can not vote for the office of President of the United States, and is subject to the will of the state. This status, as we will see in the coming sections, directly affects the economy of the Commonwealth and arguably has contributed to the current situation. Gibson & Gitter: Puerto Rican Debt Crisis Options Memorandum Page: 3 POLITICAL CORRUPTION The polity of the Commonwealth is divided among three general political movements: Independence, Status Quo (e.g. remaining a Commonwealth territory of the United States) and Statehood. The political parties that favor one of these outcomes for Puerto Rico have regularly ‘bought’ popular support in the form of government give backs to industries, union workers and other influential political participants. These political favors have taken (though not limited to), in the case of the Teachers Union, the form of a holiday bonus not just in December, but also a second one in the middle of summer.11 This is just one example, there are many items in the Puerto Rican budget which are political favors to groups that supported the current government. It is political suicide to remove these favors and as these favors grew, so did the fiscal budget of the island. Instead of raising funds for the national budget, the Commonwealth took out bonds to pay its obligations when there were budget shortfalls. While some have claimed recently that political corruption and favors are the root of the Commonwealth’s problems, I believe that the problem is far more complex than just these items in the budget, since simply removing these from the Puerto Rican budget would not balance the budget, and there would still be a shortfall between receipts and expenditures. UNDERGROUND ECONOMY Puerto Rico suffers from large underground cash economies.12 While the drug trade is one of these underground economies it is a problem both in the Commonwealth as well as in the states in general. Where Puerto Rico suffers is with small cash businesses which do not report income and pay taxes.13 These types of businesses are all over the island in the form of farm stands, lechoneras, and other businesses. Enforcement of tax levies is scant, if present at all. The lost revenues from these businesses certainly adds to the revenue problems facing the island, but by itself is only a small portion of the problem and compounds upon the other structural inefficacies.14 TRADE POLICY In an attempt by the Puerto Rican Government to increase tax revenues over the years, it instituted a 6.6% export tax. All products that leave the island are subject to this special tariff.15 While this tariff does not impact exports from the island to the Mainland United States it does effect exports to other nations. This, arguably, has impacted local agriculture exports and other exports. In fact, over the past few decades Puerto Rican exports have dropped along with economic output, which had created a vicious cycle of decreased economic output leading to decreased exports, ad infinitum. Breaking this economic trade cycle could help ameliorate the fiscal problems facing the island. EMIGRATION Gibson & Gitter: Puerto Rican Debt Crisis Options Memorandum Page: 4 Due to the economic issues facing the island, most residents of the island can get better jobs and live better economic lives on the mainland of the United States. Since they are citizens, they can freely seek work in any of the States. The loss of educated residents on the island, who can arguably do better in the Mainland United States, and have been leaving in droves for decades, has been a drain on the workforce and added to the economic problems facing the Commonwealth. This drain on the workforce has also added to the economic problems facing the Commonwealth.16 GOING FORWARD How should we look at potential options for the Commonwealth? While some in the financial sector want the island to institute austerity measures, this will only deepen the economic problems. Unlike other countries, which have had major budget issues and faced austerity, Puerto Rican residents can fly anywhere in the United States and as the population declines on the island, so will future tax revenues creating a downward spiral. Arguably the financial sector has a vested interest in the islands natural resources, which have been protected from strip mining and other industrial activities. Austerity, prima facie, will only guarantee the eventual collapse of the Commonwealth and the exploitation of the island’s natural resources. John Rawls suggests that, when thinking about the Justness of policy, we should maximize liberty while simultaneously arranging social goods and inequalities in such a way that they are to the greatest benefit to the least advantaged, and that we should do this from “behind the veil of ignorance”. That is, without taking into account our own position in life, ignorant of our station and our own wealth.17 It is hard to argue that the Commonwealth is severely disadvantaged by the status quo relationship with the United States and it is incumbent upon the Commonwealth and the United States to address the fiscal issues facing Puerto Rico while maximizing the liberty of the people of Puerto Rico and benefiting the least advantaged: the people of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. Today, the Commonwealth is faced with a debt crisis that could, at a minimum, send the island into fiscal crisis and cause deep and lasting negative effects to the United States Municipal Bond Market with concurrent negative implications for the stock market, savings, investment, and other areas of the general economy. Additionally, the loss in value to personal pensions, mutual funds, and individual investment accounts could be catastrophic. While it would be ideal to prevent a Puerto Rican municipal debt default, and there are interventions that would allow for this, a robust action should deal with both the immediate situation and help to shore up the Puerto Rican economy so that it can become sustainable and self-sufficient in the future while keeping in mind the history of American colonialism and how that effects the perception of Federal intervention.18 Gibson & Gitter: Puerto Rican Debt Crisis Options Memorandum Page: 5 OPTIONS ARE AVAILABLE TO DIFFERENT GOVERNMENTAL ACTORS In general, given the political status of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, options to attenuate this fiscal crisis fall into three general areas: Bi-lateral action by both the United States Federal Government and the Government of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico and unilateral action on the part of either the Commonwealth or the United States. Given the political structure of the Commonwealth, and the legal supremacy of the United States over the island’s government,19,20 looking at the attenuating options within these categories is important with respects to analyzing whether unilateral action by the United States could be viewed as a return to colonial era supremacy of the islands population.21 In an effort to explore options regarding a Puerto Rican Debt default we will begin with options that are unilateral to the Commonwealth to explore potential fixes that would leave Puerto Rico with the greatest amount of autonomy while staving off the fiscal crisis. Second, we will look at bilateral action between the Federal and Puerto Rican Governments. Finally, we will look at actions that the United States could make unilaterally. UNILATERAL ACTION BY PUERTO RICO INDEPENDENCE The question of Puerto Rican independence has been one of concern for the islands’ people since that appropriation of the island by the United States during the SpanishAmerican War.22 Since this is a question that the people have to answer, we will spend little time discussing this here except to warn that independence, though it may offer a short term salve to the debt burden, would also mean that the Commonwealth would be without access to international bond markets to build its economy as an independent state for some time following a default and transition to an independent nation. Further, while there is little case law on the matter, there is a question as to whether or not the United States may be legally responsible for any debt discharged in this manner. The debt was incurred by a territory of the United States, and though acting independently, there is a question of whether or not the United States may ultimately be the legal debtor should Puerto Rico decide to terminate its relationship with the United States.23 For lack of a better metaphor, and without meaning any disrespect but rather commenting on the legal relationship between the United States and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, the relationship is much like a child and parent, and legally, a parent can be held responsible for the actions of their ward. If the United States is ultimately responsible for the territories under is purview, then it is in the best interests of the United States to work with the Commonwealth to find a better, more equitable, solution to the current debt crisis. DEFAULT AND LEAVE THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT TO FIX OR ATTEMPT TO NEGOTIATE Gibson & Gitter: Puerto Rican Debt Crisis Options Memorandum Page: 6 The Puerto Rican Government could, in theory, default and claim that they have no choice. In this case they would certainly be sued by their creditors in Federal Court. There is a potential legal claim that since the United States Government has supremacy over the Commonwealth, that the ultimate creditor is in fact the United States Federal Government, as stated previously. This action would likely leave the island and its government as a pariah within the United States and could lead to the Federal Government going back to Colonial era rule of the island. Short of just defaulting and leaving the Federal Government to figure out the default crisis, the Puerto Rican Government could attempt to negotiate with creditors if no other access to other remediating options is given to the island under Federal Law. So far creditors have been unwilling to negotiate with the islands’ government. The creditors are savvy, they know the legal rules and the fact that Puerto Rico does not have access to bankruptcy protections, and that they can force the island’s hand, and the Federal Government’s hand, as well, to get their money back without negotiating. Given the general state of Wall Street it is the opinion of these authors that general default is not realistic, that it is unlikely given the status of the island and the remedies it can seek, that creditors will negotiate or accept anything less then what they want. The only way this reality changes, and gives the island’s government options to act unilaterally without default, is if the island has access to options under the law that it does not currently have. These options are discussed in the Unilateral Action by the United States section bellow. TAX REFORM Much of a plan to address the long-term fiscal stability of Puerto Rico would necessarily focus on tax reform. An increase in revenue would allow for an increase in tax collection. With the precarious economic state of the Commonwealth, it would be imprudent to raise taxes, and to instate them where there are currently none, without careful consideration as to how this might affect the already unwelcoming business climate. To keep from disproportionately affecting business, a tax hike on self-employed and high-income workers would be an appropriate start. This would prevent further hostile measures, while incentivizing market participation. The island needs to be sure that it employs policy welcoming to the type of investment that multinational corporations bring, but a recent excise tax predominately impacting multinational corporations has brought in significant government revenue. The public sector has been assessed, and taxes have been raised on such commodities as water and fuel. Evaluations of the aforementioned corporate taxes should be accompanied by those of consumer and property taxes, as well. The New York Federal Reserve has created a study of the potential for economic stabilization in Puerto Rico, and Gibson & Gitter: Puerto Rican Debt Crisis Options Memorandum Page: 7 the Commonwealth has consulted with experts to consider expedient changes to the system. A sustainable method of paying off debt is necessary to the future of the island’s economy. BILATERAL ACTION BY THE UNITED STATES AND PUERTO RICO STATEHOOD Entrance into the Union as a state should be explored. This option requires a vote by Congress and a referendum plebiscite vote in Puerto Rico in order to change its status. Statehood would allow Puerto Rico to declare bankruptcy, and take action to assess and pay down debt. Unfriendly economic conditions associated with the Jones Act would be lifted with entrance into the United States, likely subsequently improving market conditions and unemployment rates. Overall amelioration of the economic crisis becomes possible with the status change to Puerto Rican statehood. Restoration of a working and thriving economy would create revenue both for the Federal Government as well as the Commonwealth. New fiscal policy is accompanied by representation in the Capitol. Under current conditions, Puerto Rico would add 5 new seats to the House.24 This has potential to affect the representation of a number of other states, many of which are already set to lose a representative in coming adjustments. This would likely impede the process, as would the uncertain identity of the 7 total seats. This would be the largest introduction of a Latina/o delegation in Congressional history. The political leanings of Puerto Rican candidates are as of yet identified, and their election to the United States Legislature could upend the status quo. With structural changes to the Legislature and the electorate generally, it is likely that politics would be the greatest barrier to the statehood option for Puerto Rico. UNILATERAL ACTION BY THE UNITED STATES EXTEND CHAPTER 9 MUNICIPAL BANKRUPTCY Chapter 9 Municipal Bankruptcy provides a mechanism for municipalities to restructure debt via a defined court process.25 This is a mechanism that is allowed to all municipalities within the fifty-states but is not extended to the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico or other territorial possessions to restructure public debt that is no longer serviceable by the municipal organization. While this is not an option available to the State government, it is available to independent government agencies. This type of debt accounts for a large portion of the public debt that is burdening the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and access to this option would allow the island and its independent agencies to get a handle on, at least, a large portion of the debt. Gibson & Gitter: Puerto Rican Debt Crisis Options Memorandum Page: 8 Having said this, investors bought Puerto Rican sovereign debt for a number of reasons. First, the island’s debt is quadruple exempt (that is, as a function of law, Puerto Rican Municipal Bonds are exempt for taxes from Federal, State, and Local Government as well as from the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico) from taxes on the gains. Second, the island is legislatively barred from defaulting on its debt. The fact that the Commonwealth does not have the funds is a peripheral concern. Since investors bought the debt under these circumstances, it is likely that if the United States were to retroactively extend Chapter 9 bankruptcy protections that investors would sue the United States federal government for any losses sustained as a result. If this is found to be a reasonable disquiet, then this outcome of extending Chapter 9 municipal bankruptcy must be considered in putting together a final recommendation. FISCAL BAILOUT The territory has asserted its inability to pay its approximately $72 billion in debts, and is attempting to restructure its debt independent of access to Chapter 9 protections. Many of Puerto Rico’s bond issuers are already under the leadership of restructuring officers. Even with officers working to restructure the debt the Commonwealth is still on the brink of default. As United States territory, a declaration of bankruptcy receives no legislative acknowledgement. A bailout could help Puerto Rico to whittle away at its enormous composite debt. Installation of a board to audit institutions would determine where there is still credit worthiness and allow insolvent institutions to dismantle without fallout. With debt rated abysmally low, central banks would step in to help with liquidity and healthy banks would require recapitalization, and the U.S. should take an ownership interest thereto. Further economic stimulation, including interest rate cuts, should be explored. A board of overseers would be installed to supervise implementation of programs and their conditions in their entirety. The insinuations of such a weighty action have potential to generate pushback on the island. Historically, treatment of the territory has not been to its benefit, and in keeping with the conditions of a bailout, there might be dangers associated with a unilateral approach by the Federal Government. A bilateral tactic could have merit, and be a political necessity to avert feelings of hostility toward the United States by the Puerto Rican people. Current reactions to commonwealth commissioner Pedro Pierluisi’s introduction in Congress of a bill to grant Puerto Rico Chapter 9 protections, and a corresponding Senate bill, are a great indication of the present attitude towards a civic bailout. The opposition in the House and Senate rules out any immediate action and likely makes this option impractical. Gibson & Gitter: Puerto Rican Debt Crisis Options Memorandum Page: 9 REENACT AND RESTRUCTURE THE 936 TAX CREDIT In 2006 the 936 Puerto Rico and possession tax credit, 26 which gave incentives to corporations to invest in Puerto Rico, expired. This program was enacted in 1986 and got severe criticism due to the program acting more as a tax shelter for corporations than actually providing economic growth for the island, and this was detailed in a 1993 GAO report27 titled “Puerto Rico and the 936 Tax Credit.” While the intent of the program was to encourage companies to create jobs within the Commonwealth, it was common for corporations to open offices with one employee to take advantage of the tax credit28. While economic growth on the island was anemic, and after the expiration of this credit it remains anemic with unemployment hovering around 12%,29 over double that of the mainland United States, the idea of a tax credit to encourage companies to invest in jobs on the island is not a bad idea, it was just poorly conceived in 1986. One option that the United States has would be to encourage economic growth in the Commonwealth with a renewed program like that of the 936 tax credit. The problem with the original 936 program was that it was tied to a company having a presence on the island. Like Microsoft did, by simply having an employee and a physical office presence, corporations could repatriate money to the island and not pay up to 80% of the Federal tax due on that income.30 Obviously, this was a flawed program allowing corporations to avoid paying corporate income tax and without actually creating jobs and boosting the islands economy. A revised version of this program might look like a worker tax credit. For example, every job created and given to an existing resident on the island would be a better approach. This would work by the company providing documentation that: 1.) the company is headquartered outside the island, 2.) that this is a newly created job, 3.) for each employee proof that the worker has lived on the island for at least two years, 4.) certification that the job is a permanent position. One this has been certified, for each year that the job and employment exists, a deduction against profits for up to 100% of the salary paid would be available to the company to offset tax liability on profits derived from its activities as a whole. By attaching the tax credit to actual jobs and requiring documentation for such, we can incentivize creating jobs. However, in short this does not help ameliorate the dire situation right now. Admittedly, reauthorizing a new, revamped, version of the 936 tax credit is not going to solve the problems facing the island today, but by shoring up the economy over the coming years if a bailout, or restructure requires not writing off debt in the short and long term, but rather deferring those payments under new terms, then the current economy would likely not be able to sustain that in the long run. Encouraging Gibson & Gitter: Puerto Rican Debt Crisis Options Memorandum Page: 10 a robust economy on the island where there are increased tax revenues would ensure the future stability of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, regardless of any short term fixes. SYSTEMIC PROBLEMS RELATED TO ALL SOLUTIONS The sordid history of American colonialism affects every option presented here. Since the United States gave Puerto Rico self-governing autonomy in the 1950’s the primary barrier to the People of Puerto Rico voting for statehood has been a worry that assimilating as a State and not a territorial commonwealth would mean the end of the Puerto Rican/Latino culture that defines the island’s people. Independence is likely an option that is not feasible for strict economic reasons which leaves either bilateral action between the Commonwealth and the United States or unilateral action by the United States as directly viable options. However, whatever action is to be taken and advocated it must be an option, or options, that cannot be seen by the people of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico as a return to American colonialism, removing or stripping the rights of the people of Puerto Rico, or infringing on what sovereignty that it currently has as a territorial commonwealth state.31,32 Gibson & Gitter: Puerto Rican Debt Crisis Options Memorandum Page: 11 REFERENCES Reuters. (2015a). UPDATE 1-Puerto Rico tax revenue drops 14.1 percent in May -Treasury. Retrieved September 4, 2015, from http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/06/12/usa-puertorico-taxidUSL1N0YY0XK20150612 2 Moody’s. (2105). Moody’s downgrades Puerto Rico GOs and COFINA Sr Bonds to Caa3 from Caa2; outlook negative. Retrieved September 4, 2015, from https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodysdowngrades-Puerto-Rico-GOs-and-COFINA-Sr-Bonds-to--PR_329297 3 Reuters. (2015b). S&P downgrades Puerto Rico debt to “CCC+” from “B.” Retrieved September 4, 2015, from http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/04/25/usa-puertorico-sp-idUSL1N0XM01I20150425 4 Reuters. (2015c). UPDATE 2-S&P cuts Puerto Rico rating, says default seems inevitable. Retrieved September 4, 2015, from http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/06/30/sp-puertoricoidUSL3N0ZG1UQ20150630 5 Timiraos, N. (2015). Puerto Rico Has No Easy Path Out of Debt Crisis. Retrieved September 4, 2015, from http://www.wsj.com/articles/puerto-rico-has-no-easy-path-out-of-debt-crisis-1435526355 6 Yglesias, M. (2015). The Puerto Rico crisis, explained. Retrieved September 4, 2015, from http://www.vox.com/2015/7/1/8872553/puerto-rico-crisis 7 White, G. B. (2015). Puerto Rico’s Economy Is in Trouble. The Atlantic. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/06/puerto-rico-debt-crisis/397241/ 8 D’Vera, C., & Patten, E. (2015). Puerto Rican Population Declines on Island, Grows on U.S. Mainland. Retrieved September 4, 2015, from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2014/08/11/puerto-ricanpopulation-declines-on-island-grows-on-u-s-mainland/ 9 Marquez, C., & Ferre, J. (2010). Puerto Rico’s underground economy estimated at $20 billion a year. Caribbean Business. Retrieved from http://www.caribbeanbusinesspr.com/prnt_ed/news02.php?nw_id=4566&ct_id=0 10 http://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/jonesact.html 11 Sanabria-Valentin, Edgardo L. (2015). Personal Communication. 12 Duany, J., & US Census Bureau. (n.d.). The Census Undercount, The Underground Economy and Undocumented Migration: The case of Dominicans in Santurce, Puerto Rico. Retrieved September 13, 2015, from https://www.census.gov/srd/papers/pdf/ev92-17.pdf 13 Lopez, L. (2014). Desperate for taxes, Puerto Rico tries to get grip on underground economy | Reuters. Retrieved September 13, 2015, from http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/04/09/us-usa-puertoricoeconomy-insight-idUSBREA380BS20140409 14 Marquez, C., & Ferre, J. (2010). Puerto Rico’s underground economy estimated at $20 billion a year. Caribbean Business. Retrieved from http://www.caribbeanbusinesspr.com/prnt_ed/news02.php?nw_id=4566&ct_id=0 15United States Customs and Border Protection (2013). Regulations for shipping goods to a company in Puerto Rico for resale. Retrieved September 13, 2015, from https://help.cbp.gov/app/answers/detail/a_id/326/~/regulations-for-shipping-goods-to-a-companyin-puerto-rico-for-resale 16 Watch, E. (2010). Puerto Rico Trade, Exports and Imports | Economy Watch. Retrieved September 13, 2015, from http://www.economywatch.com/world_economy/puerto-rico/export-import.html 17 Rawls, J. (1999). A Theory of Justice (Revised Ed). Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. 18 Neuman, G. L., & Brown-Nagin, T. (Eds.). (2015). Reconsidering the Insular Cases: The Past and Future of the American Empire. Cambridge, MA: Human Rights Program at Harvard Law School. 19 Denis, N. (2015). War Against All Puerto Ricans: Revolution and Terror in America’s Colony. New York, NY: Nation Books. 1 Gibson & Gitter: Puerto Rican Debt Crisis Options Memorandum Page: 12 Neuman, G. L., & Brown-Nagin, T. (Eds.). (2015). Reconsidering the Insular Cases: The Past and Future of the American Empire. Cambridge, MA: Human Rights Program at Harvard Law School. 21 Denis, N. (2015). War Against All Puerto Ricans: Revolution and Terror in America’s Colony. New York, NY: Nation Books. 22 Denis, N. (2015). War Against All Puerto Ricans: Revolution and Terror in America’s Colony. New York, NY: Nation Books. 23 Neuman, G. L., & Brown-Nagin, T. (Eds.). (2015). Reconsidering the Insular Cases: The Past and Future of the American Empire. Cambridge, MA: Human Rights Program at Harvard Law School. 24 Poston, D., & Nichole, D. (2012). The Social Contract - Which States Lose House Seats If Puerto Rico Becomes a State? Retrieved October 8, 2015, from http://www.thesocialcontract.com/artman2/publish/tsc_22_2/tsc_22_2_poston_farris.shtml 25 United States Courts. (n.d.). Chapter 9 Bankruptcy Basics. Retrieved October 8, 2015, from http://www.uscourts.gov/services-forms/bankruptcy/bankruptcy-basics/chapter-9-bankruptcybasics 26 United States Courts. (n.d.). Chapter 9 Bankruptcy Basics. Retrieved October 8, 2015, from http://www.uscourts.gov/services-forms/bankruptcy/bankruptcy-basics/chapter-9-bankruptcybasics 27 Government Acountability Office. (1993). Puerto Rico and the 936 Tax Credit (No. GAO/GGD-93-109). Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.gao.gov/assets/220/218131.pdf 28 Puerto Rico Report. (2012). Foreign Taxation in Puerto Rico. Retrieved October 8, 2015, from http://www.puertoricoreport.com/foreign-taxation-in-puerto-rico/ 29 Puerto Rico Unemployment Rate. (2015). Retrieved October 8, 2015, from http://www.tradingeconomics.com/puerto-rico/unemployment-rate 30 Puerto Rico Report. (2012). Foreign Taxation in Puerto Rico. Retrieved October 8, 2015, from http://www.puertoricoreport.com/foreign-taxation-in-puerto-rico/ 31 Denis, N. (2015). War Against All Puerto Ricans: Revolution and Terror in America’s Colony. New York, NY: Nation Books. 32 Neuman, G. L., & Brown-Nagin, T. (Eds.). (2015). Reconsidering the Insular Cases: The Past and Future of the American Empire. Cambridge, MA: Human Rights Program at Harvard Law School. 20