Obscenity - College of Education

advertisement

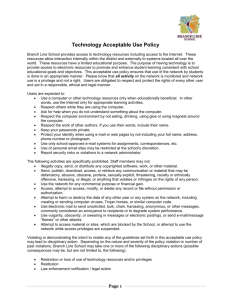

Lightning Case Module #003 Obscenity and The First Amendment Dr. Brad Burenheide Kansas State University College of Education Contents For Teachers: Overview of Lightning Case Module 3 Introduction to the Controversy 7 The Cases 8 Alberts v. California (1956) Stanley v. Georgia (1968) Miller v. California (1971) Jenkins v. Georgia (1973) New York v. Ferber (1981) Osborne v. Ohio (1989) For Teachers: More About the Cases (decisions and more) 10 Final Assessment: Reading a Professional Journal Article 12 Bibliography 13 For Teachers: Overview of Lightning Case Model Under the ruling levied in Marbury v. Madison, the Supreme Court became the institution in the American legal system that serves as the ultimate arbiter of issues of constitutional law. In the opinion, Justice John Marshal noted that “the judicial power of the United states is extended to all cases arising under the Constitution…It is also not entirely unworthy of observation that, in declaring what shall be the supreme law of the land, the Constitution, itself is first mentioned, and not the laws of the United States generally, but those only which shall be made in pursuance of the Constitution, have the rank (Marbury v. Madison, 1803).” Under this system of judicial review, it becomes extremely important for students to understand the rights contained with the Constitution and the subsequent Bill of Rights as the Constitution is the ultimate law of the United States. As precedents developed, the scope of the rights of citizens has evolved over time. Thus, it becomes important for citizens to follow this evolution and how the courts currently measure these rights. As Vontz and Leming noted, the use of Supreme Court cases lend themselves well to certain methods (Vontz & Leming, 2003). But, in this specific case, it is important to realize that the method must be integrated with the content. Vontz and Lemming further suggest civics educators who utilize active and participatory strategies, analyze documents and issues, teach with relevant topics, and teach civics content relevant to democratic citizenship can best motivate students to acquire knowledge of citizenship. One of the means of doing this is through the analysis of Supreme Court cases. The case study method of court decisions can engage students in gaining key knowledge through the analysis of important cases (McDonnell, 2002; Long, 1994). Vontz and Leming denote however that the understanding of the “bigger topics” of citizenship can be collected from the study of Supreme Court cases than the law students analyzing cases for method and specific topics of study (Vontz & Leming, 2003). These cases can allow students to investigate facts, issues, arguments, context, civic principles, and higher order thinking skills (Knapp, 1993; Leming, 1991). While there are common strategies to dissect cases of the Supreme Court, many of them can be heavily involved and use up a large amount of time in the classroom. Hanna and Dettmer (2004) encourage the teacher when designing assessments to maintain a balance between reliability, authenticity, and economy. Reliability would be accuracy of the measurement. Authenticity deals with the real-world application of knowledge to encourage transfer of learning. Economy deals with the use of time, effort, and energy in administering the assessment. Where economy focuses on the great “enemy” of the teacher—time—the teacher must consider if the strategy is the optimal and most appropriate use of time. In their article encouraging the use of Supreme Court cases, Vontz and Leming (2003) called for the use of Socratic seminars and moot court cases to effectively analyze the thinking of the court, the institution of the case in an historical context, and by taking an active role in the participating of the activity, becoming content experts of the case. But is this the best use of time in the classroom? Does the depth of content in this instance supersede the coverage of breadth? This study intends to analyze this question by employing a strategy that employs a significant quantity of cases without sacrificing the apparent quality of learning. Description of the Model The “Lightning Case” method discussed in this study is rooted in a sound literature base of experiential learning. Kolb (1984) and Kolb and Lewis (1986) provide a model for experiential learning or having students actively engaged in testing explanatory ideas created by the student. Mukhamedyarova (2005) explored the idea of interactive learning and evaluated five strategies commonly used. O’Brien (2003) discussed a model for students to engage in historical prediction making. Finally, Hess (2002) and Parker (2003) illuminated the nature of controversial deliberation in the classroom and provided guidelines for teachers to follow. Through the sources cited above, a model was constructed that causes students to be actively engaged in the analysis of cases, make predictions based upon their knowledge of the Constitution, and discuss with fellow students, albeit briefly, about their decisions and rationale. Figure 1 provides a visual overview of the model. Figure 1: An Overview of the “Lightning Case” Model Teacher Guides Overview of Right/Concept in Question Students deliberate a number of illustrative cases dealing with the concept. Students tackle a Students conceptualize number of the boundscases of the illustrative right/concept in the eyes dealing with the of the law. concept. The model provides students with the opportunity to utilize several cases to develop their own conceptualization of the boundaries of liberty within society and in the “eyes of the law.” The teacher provides a brief overview of the rights enumerated in the Constitution based upon the specific concept that will be addressed. After this introduction, several cases are presented to the student in a written or oral format with a short synopsis of the key facts of illustrative Supreme Court cases. Pending on the teacher’s preference, students may be given the opportunity to deliberate with their classmates, or they will create their own decision of the case. After the court’s actual decisions are shared with the students with brief rationale for their decision, students conceptualize the boundary of the right or concept discussed in the “Lightning Case” session. Introduction to the Controversy What is art to one person may be offensive and morally reprehensible to others. The question becomes what is obscenity? As defined by dictionary.com, obscenity is: “the character or quality of being obscene, indecency; lewdness” Obscene is defined: “offensive to morality or decency; indecent; depraved;” OR “causing uncontrolled sexual desire;” OR “abominable; disgusting; repulsive.” The difficulty in defining this term is indicative of how difficult it can be to explain in our society. Whether the case law deals with the use of swear words in public (ala George Carlin in the 1970’s) or cases dealing with the use and distribution of pornography, obscenity has been at the heart of our country’s moral dilemmas for quite some time, especially in the age of enhanced technology and media. As an example of the difficulty the court has had with defining it, Justice Potter Stewart wrote in his concurring opinion in Jacobellis v. Ohio (1964): “I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description [“hard-core pornography”]; and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it and the motion picture in this case is not that.” This module takes students through six that tackle this tough and controversial issue. In an ironic twist, I suggest the teacher carefully preview the module and see if it is appropriate for their class and students. The final assessment asks students to read a professional academic journal article detailing a proposed revisiting of the obscenity standards in society. Students are asked to read the article, and then provide a written response to the article. This is in conjunction with a more mature audience who can handle the seriousness and demeanor of the subject matter and content. The Cases Alberts v. California (1956) Overview of the Case Alberts conducted a mail-order business which sold sexually explicit materials. He was convicted in a Municipal Court in California on a misdemeanor complaint which found him guilty of selling lewd and obscene books and of composing and publishing an obscene advertisement for his products. Question Did the California law on obscenity dealing with the selling and distribution of obscene literature violate Alberts freedom of speech and press as guaranteed by the First Amendment? Stanley v. Georgia (1968) Overview of the Case Law enforcement officers, under the authority of a warrant, searched Stanley's home pursuant to an investigation of his alleged bookmaking activities. During the search, the officers found three reels of eight-millimeter film. The officers viewed the films, concluded they were obscene, and seized them. Stanley was then tried and convicted under a Georgia law prohibiting the possession of obscene materials. Question Did the Georgia statute infringe upon the freedom of expression protected by the First Amendment? Miller v.California (1971) Overview of the Case Miller, after conducting a mass mailing campaign to advertise the sale of “adult” material, was convicted of violating a California statute prohibiting the distribution of obscene material. Some unwilling recipients of Miller’s brochures complained ot the police, initiating the legal proceedings. Question Is the sale and distribution of obscene materials by mail protected under the first amendment? Jenkins v. Georgia (1973) Overview of the Case An Albany, Georgia theater manager was convicted under a Georgia obscenity law when he showed the critically acclaimed film “Carnal Knowledge.” The film explored social conceptions of sexuality and starred Jack Nichiolson and Ann Margaret. Question Did the manager’s conviction violate the First and Fourteenth Amendment? New York v. Ferber (1981) Overview of the Case A New York child pornography law prohibited persons from knowingly promoting sexual performances by children under the age of sixteen by distributing material which depicts such performances. Question Did the law violate the First and Fourteenth Amendments? Osborne v. Ohio (1989) Overview of the Case After obtaining a warrant, Ohio police searched the home of Clyde Osborne and found explicit pictures of naked, sexually aroused male adolescents. Osborne was then prosecuted and found guilty of violating an Ohio law that made the possession of child pornography illegal. Question Did Ohio’s ban on the possession of child pornography violate the First Amendment? For Teachers: More About the Cases Alberts v. California (1956) The Court, speaking through Justice William J. Brennan, Jr. held 6 to 3 that obscenity was not "within the area of constitutionally protected speech or press.” Thus the California law was upheld. Stanley v. Georgia (1968) In a unanimous 9-0 decision, the Court held that the First and Fourteenth Amendments prohibited making private possession of obscene materials a crime. In his majority opinion, Justice Marshall noted that the rights to receive information and to personal privacy were fundamental to a free society. The Court distinguished between the mere private possession of obscene materials and the production and distribution of such materials. The latter, the Court held, could be regulated by the states. Miller v. California (1971) The court ruled 5-4 for Miller. The court stated that obscene materials did not enjoy First Amendment protection. However, the court established another test for whether or not something was obscenity: "[t]he basic guidelines for the trier of fact must be: (a) whether 'the average person, applying contemporary community standards' would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest. . . (b) whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law; and (c) whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value." The Court rejected the "utterly without redeeming social value" test of an earlier decision. Jenkins v. Georgia (1973) A unanimous Court held that the Georgia Supreme Court misapplied the obscenity test in Miller v. California Justice Rehnquist argued that Miller did not give juries “unbridled discretion” to determine what is offensive. Only material that displays “hard core” sexual conduct is prohibited. Since the movie in question did not contain scenes of that nature it merited constitutional protection. New York v. Ferber (1981) In the Court’s first examination of a statute specifically targets against child pornography, it found that the state’s interest in preventing sexual exploitation of minors was a compelling “government objective of surpassing importance.” The law was carefully drawn to protect children from the mental, physical, and sexual abuse associated with pornography while not violating the First Amendment. Osborne v. Ohio (1989) The Court held that Ohio could constitutionally proscribe the possession of child pornography. The Court argued that the case at hand was distinct from Stanley v. Georgia, "because the interest underlying child pornography prohibitions far exceed the interests justifying the Georgia law at issue in Stanley." Ohio did not rely on "a paternalistic interest in regulating Osborne's mind;" rather, Ohio merely attempted to protect the victims of child pornography. The Court argued that regulations on production and distribution of child pornography were insufficient and could not dry up the market for pornographic materials. The Court also found that an error in jury instructions in the lower courts mandated Osborne be given a new trial. Final Assessment: Revisiting Obscenity Laws Go to the following link and download the article: Scot A. Duvall, A Call for Obscenity Law Reform, 1 Wm. & Mary Bill of Rts. J. 75 (1992), http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol1/iss1/4 In this journal article, Mr. Duvall (who is now an Intellectual Property Attorney) reviews development of obscenity issues in case law and calls for a revisiting of them. After reading the article, you are asked to write a position paper on the issue of obscenity that answers the following questions: Does our society need laws to protect citizens from obscene materials? Has society changed where obscenity laws cannot keep up? Is there a way to permanently police obscenity to address concerns about its lasting social impact? What is your personal position on obscene materials? Your teacher will establish a rubric for assessing your performance on this issue. Bibliography Cover Graphic: http://www.menwithfoilhats.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/FirstAmendmentE.jpg?cda6c1 Overview of the Controversy Definition of obscenity: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/obscenity Definition of obscene: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/obscene Quote of Potter Stewart: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_know_it_when_I_see_it The Cases Alberts v. California (1956) http://www.oyez.org/cases/1950-1959/1956/1956_61 Stanley v. Georgia (1968) http://www.oyez.org/cases/1960-1969/1968/1968_293 Miller v. California (1971) http://www.oyez.org/cases/1970-1979/1971/1971_70_73 Jenkins v. Georgia (1973) http://oyez.org/cases/1970-1979/1973/1973_73_557 New York v. Ferber (1981) http://oyez.org/cases/1980-1989/1981/1981_81_55 Osborne v. Ohio (1989) http://oyez.org/cases/1980-1989/1989/1989_88_5986 Final Assessment Scot A. Duvall, A Call for Obscenity Law Reform, 1 Wm. & Mary Bill of Rts. J. 75 (1992), http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol1/iss1/4