Indigenous Knowledge - University of Warwick

advertisement

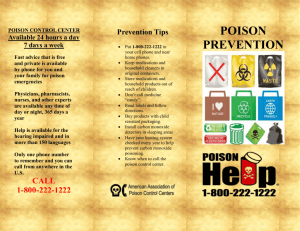

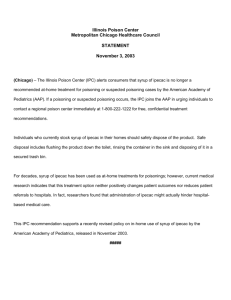

Situating Medicine: New Directions Conference, 5-6 June 2014 Centre for the History of Medicine, University of Warwick Panel: Indigenous Knowledge, Power and the Everyday ABSTRACTS David Hardiman, University of Warwick Miracle Cures for a Suffering Nation: Sai Baba of Shirdi Sai Baba of Shirdi, who died in 1918, was raised as a Muslim but is today revered as a Hindu saint. One of his most important perceived qualities was his ability to provide miraculous cures for his devotees – an effect that has continued after his death. It is argued in this paper that such an emphasis on healing the sick by saintly figures in the Hindu tradition is a relatively modern phenomenon. Earlier, while such figures were renowned for their miracles, healing played a very minor part in this. In general, their miracles were designed to worst religious rivals, and to enable them to speak truth to power. In the modern era, however, saintly figures of this sort can gain a reputation through healing in a way that is depicted as being beyond the comprehension of modern medical science. In this, such people are seen as providing living evidence of the superiority of Indian civilization and its religious beliefs. This is a move that became entangled with nationalist sentiments, so that getting the better of the 'English' doctor became a means to reveal the limited scope of Western science and culture. Although this appears to suggest that many Indians have rejected the biopolitics associated with western modernity (as defined by Michel Foucault), it is argued that there are certain elements to such biopolitics that are central to this whole process. The article illustrates this through a study of Sai Baba – a village holyman who was taken up by the Indian middle classes and made into a pan-Indian figure, with a now global presence. David Arnold, University of Warwick ‘How to Murder a Resident: Poison, Politics and India’s Toxic Transition, 1870-1914’ On 9 November 1874 an apparent attempt was made to poison Colonel Robert Phayre, the British Resident (Political Agent) to the western Indian state of Baroda, allegedly by Malharao the Gaekwar, or ruler. The poisoning can be situated within a long history of contestation over control of the state and of poison practices among India’s princely rulers. But it also represents one of the first major attempts in British India to establish scientific evidence for poisoning (in this instance arsenic and crushed diamonds) and demonstrates British concern about poisoning as a political instrument. The Baroda episode also anticipates a shift away from individual cases of homicidal poisoning to a wider social and environmental engagement with the governance of toxicity—in everyday items of consumption and use, in industrial processes and urban localities, and in common criminality. This perceptual and administrative shift (India’s ‘toxic transition’), largely complete by 1914, further illustrates the value of seeing poison as a form of indigenous knowledge and aberrant medicine. Projit Bihari Mukharji, University of Pennsylvania Whence Came the Devi? The Story of Mrs Duncan, the Bengali Goddess of Cholera The eponymous Devi arrived, for a second time, in 1987. Her first coming had been in 1922, but decades of Rationalist and Marxist dismissal had buried her deep in the bowels of the colonial and mnemonic archives. The second coming signalled a radical change of South Asian historiographic mood. Ranajit Guha had made the first efforts to resurrect the radical gods of peasant politics, but it was David Hardiman who acted as shaman to raise the Devi, in all her radicalism and ambiguity. Since then, the power of the old gods has continued to grow once again. David Arnold has seen in them a peculiarly South Asian and subaltern way of responding to epidemics. Dipesh Chakrabarty has found in them the limits of rationalist historiography and the homogenizing reach of global capital. Goddesses, vampires and many other supernatural beings have frequently become symbols of the trenchantly local, the unmistakably vernacular and the very antitheses of the cosmopolitan, especially in Histories of Medicine. Using the history of Ola Bibi, the Bengali cholera goddess, I want to interrupt this reification of the local. By recovering the forgotten historical identity of the goddess prior to her deification and historicizing the process of her deification, I seek to restore the promiscuity of the transnational and the transrational. My hope is to thereby show up the ‘translocality’ of the ‘local’ and its enchanting cosmopolitanisms.