Framing - David W. Chambers

advertisement

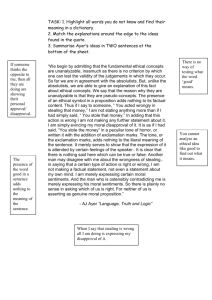

Chapter 7. Framing The nineteenth century Swiss crystalologist Louis Albert Necker, for whom the well-known “illusion” is named, had a hard time focusing on his work. Is the cube just a parlor game or an inescapable feature at the foundation of moral behavior? Figure 7.1: The Necker cube. Some observers see this cube with the front face in the lower left, the bottom line of the face being the lowest horizontal line. Others spontaneously see a different front face square positioned a bit higher in the upper right-hand part of the image. The very top horizontal line is the top of this face, and the figure recedes back and down to the left. With a little practice and letting one’s gaze wander over the entire figure, the faces can be made to pop back and forth, although it is common for one or the other to dominate. A few individuals find it hard to change and seem to get locked into whichever view suggests itself first. This is called field dependency, suggesting insufficient awareness of the context in which perceptions are embedded (Witkin and Goodenough 1981). 1 Psychologists consider extreme inability to switch perspective to be a personality disorder. It is a diagnostic characteristic of sociopaths. Authoritarian personalities also lack perspective flexibility (Adorno et al. 1950). Those who are field dependent may have resisted the discussion of RECIPROCAL MORAL AGENCY in previous chapters exactly because it requires seeing situations from others’ points of view. Others may have bristled because they “just knew” that self-interest is the ultimate ground for morality; some may have found it intuitively obvious that caring is where we have to start. Foundational realists (Cahoone 2002) who believe that some truths come with their own guarantees are likely to have inflexible views about what is right and wrong. They are also less capable of even seeing the possibility that there are alternatives. Being completely objective about it, both of the takes on the Necker cube already mentioned are artifacts. The figure is two-dimensional so nothing can “extend forward or backward.” There is a completely flat figure with two triangles, four rhomboids, and a vertical rectangle positioned exactly in the center. This is the hardest figure to see because it requires suspending the natural habit of “point of view.” The flat figure is the most “objectively real” one, but seeing it requires a new rule for describing reality. This is the Paradox of Objectivity so embedded now in science. To see “things as they are,” we must create new and artificial rules for observation. This pesky Necker cube has even more tricks up its sleeve. No one can actually see the whole cube, despite its seeming so “obvious” that we do. What is going on is lightning-quick reconstruction that is at once substantially less than we imagine and necessarily more at the same time. The episode of vision is the saccade (Pierrot-Deseilligny et al. 1995). These are very rapid (about 300 millisecond), jumpy fixations of focus. The visual field of one saccade is only about as large as a word or two of text on this page. And the patterns of moving from one saccade to the next are neither linear nor random. They are under the control of learned habits, but can be overridden partially if that serves a useful purpose. The outcomes of the first few saccades control the next ones, and that determines, in less than a second, which face we see as foremost on the Necker cube, for example. Good readers hop from the few words following capital letters to the next set trying to lace together a coherent stream of argument. They certainly do not fix on each word or letter and then extract their sense with the aid of rules from grammar and syntax. I regularly find and circle typos in published works, especially when I am reading something that is boring. We only see a few corners of the Necker Cube and fill in what we assume needs to be there. Other times we stare distractedly at it, and there is a complete absence of any neurological trace representing any feature of the figure whatsoever, even its existence. 1 It is a comfortable fiction to believe we are objectively sensing the whole visual field or pure and atomic concepts in one gulp. It is a further crude gloss to imagine that what exists in the material world uniquely determines what we see or think. We assemble the units of analysis upon which we build our understanding, and the defense of our interpretation comes later, if at all, and includes a much wider context of what “certainly must be the case” for our interpretations to be veridical. The basic building blocks we work from – perceptual ones or reasoning ones or feeling ones – are not given but selected. When philosophers work at the level of ethical principles, rational thought, or cognitive analysis, they are describing patterns in their own heads, usually very sophisticated ones built up over many years of observation and analysis. Our conceptions may overlap in productive ways with other people’s conceptions, but much mischief is possible where the assumed identity is unwarranted. We should not take it as proof that our concepts are hard reality just because they work in a general sort of way and no one objects to them. In most cases the concepts are just close enough for current needs, and others do not care that much how we imagine the world. 2 But if we learned nothing more from the Necker cube than that various disciplines can work in a field at different levels of analysis, this book will have been limp. Moral philosophy that does not assume that concepts are real primitives has been done before and is only part of the story. 3 The Necker cube was a staple tool of the Gestalt psychologists of the 1930s who insisted that we see wholes rather than assembling them out of the parts. The reason there are so few Gestalt psychologists today is that the rest of the discipline capitulated, saying in effect, “Yes, of course, that is so obvious we need not discuss it further” (Smith 1988). We may “know” that there are two primary ways and an infinite number of additional visual or analytical ways to see the Necker cube, but we can only “see” it one way at a time. It is wholly this or wholly that for us at any point. We can jump from one level of analysis to another or consider possible alternative views, but each of these views is a separate neurological event. Philosophers of science in the emergent, non-linear systems, or quantum physics tradition routinely work across levels of analysis and even whole disciplines such as physics and chemistry. We accept that all matter is composed of atoms, but that the atoms in a hot solid object are not hot. 4 A similar sort of logic has yet to be applied to the relationship between neurological and conceptual primitives. Something is going on in perception beyond just registering “reality.” This chapter will take some baby steps toward understanding that. Moral framing means seeing the world a certain way – setting it up so we can deal with it. If two individuals frame a common situation differently, each will proceed based on a different framing. They will be living in parallel worlds and not solving “the same” problem at all. That is why RMA is so powerful: it honors rather than imagining away the fact that moral agents act on the world as they see it. Our moral sensing equipment generally works this way: First we see meaningful whole engagements in a natural way. We can later take them apart for analysis if we think that would be useful, and promise not to leave parts out when we put them back together. Lacking perfect instruments for knowing what is ethical, we do the best we can. But we tend to state matters in our favor, choose standards that maximize our winning, and selectively recall the good and omit the questionable when adding up the total. For the most part we pay little attention to the fact that others are doing likewise. If we see that they have it another way, our instinct is to believe they are confused. This chapter will explore what is natural about the way we sense the world. The next chapter will show how careful we have to be in doing this because of the flagrant biases we all suffer when talking about what is good and right. I take great pains to rule out the grand dodge of ethics that sweeps everything up into the solution: “If you saw things the way I do we would probably agree.” This chapter and the next will focus on what it means to “sense” moral engagements. The nub of the argument is that we do not simply “see” them; we always “see them as being a certain way.” The fact that human behavior is built on the ways we frame the world cannot be set aside until we sort out what the world would be like without our individual framing. That would be like lifting the chair we are sitting in by pulling very hard on its bottom. The early chapters in this book assumed that there is no Archimedean point from which, if we had a “neutral place to stand” and a long enough stick, we could move the world. From here on out it will be helpful to explicitly consider whether it is possible to build a theory of community moral action without first requiring that others agree with us about our sense of things. We are going to look inside the brain. Spoiler alert: there is no requirement that we agree on ethical principles to build moral communities. Basic Framing Framing is the act of interpreting how a moral engagement, or any other important situation, appears to us. That is quite different from ethical reasoning, and different again from selecting evidence to justify a chosen behavior. Lawrence Kohlberg developed what may be the most famous ethical dilemma. It is called Heinz. In Europe, a woman is near death from a special kind of cancer. There is one drug that the doctors think might cure her. It is a form of radium that a druggist in the same town has recently discovered. The drug is expensive to make, but the druggist is charging ten times what the drug cost him to make. He paid $200 for the radium and is charging $2,000 for a small dose of the drug. The sick women’s husband, Heinz, goes to everyone he knows to borrow the money, but he can get together only about $1,000, which is half of what it costs. He tells the druggist that his wife is dying and asks him to sell the drug cheaper or let him pay later. The druggist says, “No, I discovered the drug and I’m going to make money from it.” Heinz is desperate and considers breaking into the man’s store to steal the drug for his wife. Can Heinz justify theft? Is this primarily a matter of obeying the law? Perhaps the real issue here is the absence of a caring spirit, or cajoling those who are insensitive to others’ needs. Or is the point settling on the “real” definition of fairness? Maybe it is about basic human rights. Or is it more a matter of principles, perhaps conflicting ones? The Heinz case is less about finding the answer than about shaping the question. Certainly the way we frame the question will determine which action is “right.” Kohlberg’s thinking launched a fertile theoretical and research program in the 1960s because he proposed that we grow ethically by moving from crude framings of moral engagements when we are young to more sophisticated ones. 5 Better framing leads to better resolutions, and almost all humans follow the same natural progression toward better framing as they get older. In the roughest of terms, the order of the questions in the preceding paragraph reflects this Kohlbergian path to moral maturity. First we use the rules imposed by those in authority and have a mind toward avoiding punishment. A higher level of morality involves conforming our behavior to norms common in our community. We seek to fit by saying and doing what others say and do. The highest level, according to Kohlberg, involves being able to give justifications for our actions in terms of abstract theories, independent of whether we are punished or praised or what others think of us. We anchor our actions in ethical principles. The research along these lines uses multiple cases and a scoring rubric (the best known one being the Defining Issues Test) to classify individuals by their level of moral framing or reasoning. One or two points are awarded if the issue is framed in terms of likely benefits or penalties; three or four points go to those who see issues as reflecting community standards; the top scores of 5 and 6 are for those who think in abstract philosophical terms. Kohlberg’s theory suggests that individuals develop morally, as a result of age at first, but later with help from education in ethics and also in liberal studies generally. 6 Moral development is almost entirely a matter of moving from the lowest stages of practical expediency to the middle level of peer convention. A small fraction of the thousands and thousands of people tested all over the world exhibit any tendency to view moral challenges as involving abstract principles. In a famous irony, one of Kohlberg’s students, Carol Gilligan (1982), helped kick start feminist philosophy by objecting that Kohlberg was right to see ethics as a matter of framing, but he had imposed an inappropriate male frame on all of ethics. Gilligan argued, based on her work with women seeking abortions, that woman see morality through a master frame of for caring for others. There is scant research to show individuals who sense the world at the “higher” levels of ethical principles actually behave differently from those who take a less abstract view. 7 The way we frame moral engagements affects how we structure them, but it does not necessarily carry through to how we resolve them. Why Framing Matters There is an obvious sense in which alternative frames for a given situation may lead to different behavior. Parents hear a report about an “inappropriate remark” a teacher might have made to their junior high school daughter. The “right thing to do” will depend on whether the parents feel their daughter who reported this is trustworthy, whether they think the teacher is closer to being a free spirit or a slime ball, what they know of the law, and even whether they think a large cash settlement might be possible. There is manifest danger in using examples such as this. Based on the first sentence alone, and before considering some of the alternative interpretations, most readers will have decided whether the teacher is guilty or not, and the rest of the ethical analysis will hang on that. Our judgement maker works very, very fast. The optional justification feature is quite slow. That may illustrate my point, but makes it difficult to “justify” it. What Framing Is We live in an autopilot world. Framing means registering when changes in our environment require a response. We consider action when we recognize an important difference between our base templates for what should be there and what seems to be happening. Framing matters when new conditions call for new reactions. This can involve external situations, as a TV news report or a scowl. It can just as well be internal. I am ready to do something as soon as I realize that I am bored or when I suspect I am about to say something logically inconsistent. Changes that are not noticed are not framed. All registered changes are interpreted; they are meaningful in the sense that they represent potential improvements or possible degradations – depending on how react to them. It is time to revisit the pepper spraying incident on the UC Davis campus that was introduced in Chapter 1. The encounter was not well managed because it was misframed. If the administration had considered the students’ perspective they would have seen that RMA pointed to a Next Best solution, in Engagement #20. “No force” in the face of “resistance” projects a [4 3] outcome that is stable and would be maintained and defended by both parties. The only decision rule for the full matrix that involves the use of force by the administration would be the unhappy CONTEMPT approach. More likely what happened was that the administration considered neither the perspective of the students or campus security. It appears that both administration and security used a strategy based on maximizing what they wanted, assuming that students framed the matter exactly the same way. The external reports that were so critical of the way the matter was managed fo1cused exactly on Chancellor Katehi’s failure to get the campus police and the students on the same page. The moral mistake was inconsistent framing. The chief of campus security did not attend the meeting where contingency plans were developed, nor did she review the plans. No arrangements were made for transporting students should it become necessary to make arrests. The chancellor and her team addressed a moral engagement only in their imaginations. They thought they were dealing with off-campus agitators; they were not. As the chancellor noted: “Everything would have been just fine if the students had acted the way we expected them to.” When the real problem was recognized as requiring a reframing -- one that took into account the moral agency of the students -- the attempts to improvise on the spot were bungled. The Principle Problem Sometimes ethical arguments sound like this: “You should give way because my framing is better than yours.” We hear, “Surely you cannot deny that the United States public debt is vast and will impose an unreasonable burden on our grandchildren unless we curb spending now.” “Substantial prudent expenditures,” it is countered, “on infrastructure are needed now to ensure a healthy future for the country.” It is tenuous to argue as though we knew what was best for others in the future. It is further risky to believe that only one principle, typically ours, is “correct” in each case. The prospect of arguing our way to a resolution of the abortion issue is 1 vanishingly small. It is possible to count votes or bow to greater pressure or willingness to make sacrifices for one position or another. But it is unclear what it would mean to say that one argument is “better” than another. That would necessitate having a higher-order principle for getting the other principles lined up in the right order. But you might not accept my master principle, and why should I accept yours? This way of arguing entirely misses the point. We should be looking for what two agents can agree is the best way toward a better future given how the matter now stands, not which offers the more attractive justification. When the question is framed as a contest between principles, with the assumption that the “best” principle wins and controls behavior, I call this the Principle Problem. Here is an example. When Charles II was restored as monarch of England following the reign of Oliver Cromwell, Parliament passed in 1662 a set of laws known as the Acts of Uniformity. They reestablished the ascendency of the Church of England. The guiding principle was that there was no higher good than protecting Englishmen from soul-damning adulterations to the Book of Common Prayer and administration of the sacraments or preaching by any other than ordained Anglican clergy. That was seen as a high principle and one worthy to be enforced by firm laws. For example, all who refused to swear to it were barred from holding public office or attending university, and dissenting clergy were put out of a living. In 1664, the act was amended to ban conventicles, the assembling of more than five people not from the same family, from discussion of spiritual matters. But Daniel Defoe, in his A Journal of the Plague Year, explains how during 1664-65 the act was laid aside. The clergy of the Established Church had followed the court to Oxford to avoid the contagion in large cities thus leaving most English Christians without the benefit of clergy. The Church of England was pleased to open churches and attending to the dead to any interested dissenting minister. Once the plague had passed, however, the Acts of Uniformity were further amended to prevent non-conforming clergy from coming within five miles of any incorporated area or any place they had formerly lived. To our modern ears, this seems like draconian reframing for selfish ends. It is, in fact, one of the most pernicious moral abuses – writing laws that force an unfavorable framing on others and then enforcing them selectively. Almost all cases of social inequality, from sexual discrimination to income inequality, can be interpreted in terms of government-sponsored malframing. Much mischief has worn the gown of enforcing the highest principles. Using an approach based on the belief that “my principle is best” condemns one to using a BEST STRATEGY, BEST OUTCOME, ALTRUISM, DECEPTION, or COERCION decision rule. My best outcome, for example, is the one that guarantees that my principle controls the outcome. My use of a charity rule presumed that I know better how to help you than you do. As we saw in Chapters 3 and 4, all of these approaches based on following only our own way, even our own principled way, are less effective than RMA. RMA is better because it is “double-framed.” Ethical principles do matter. We just tend to use them for the wrong purposes. They belong in the framing matrix for moral engagements; they contribute to our view of what a better future world might look like. You will naturally put your principles in your framing matrix, and I will put mine in my framing matrix. But they are out of place when we try to use them decide which joint strategy is best. That necessitates your accepting my principles as dominating yours or vice versa. If we agree in principle or just do not care very much, so much the better. But we need an approach to morality that is not based on privileging one party’s values over another’s. All along, the trap has been a belief that moral choice is about articulating sound justifications. That is ethical reasoning. We might win the argument and force others to acknowledge our principles, but still not make a better world. Dissenters took the oath under Charles II in order to get a college education or retain a political office. Chancellor Katehi might get students to acknowledge that respect for other students is a worthy ethical good without getting students to abandon their tent city. The students might very well believe that safety is important, but not the most important consideration. How We See Moral Engagements Framing is not picking elements to make our case. It is registering the situation we face as honestly as possible. There are three characteristics of framing. We cannot see moral engagements other than as (a) what is immediately available (b) value-drenched reality that (c) leans toward certain futures instead of others. Framing is a gerund; it is both the process of creating something and it is what is created during that process. It is our warrant, promise, pattern, rough draft, or plan. One of my professors when I was in graduate school was Jerome Bruner. He was wellknown as an educational theorist, but some of his early research was in the relationship between perception and value. He constructed a small booth as a research apparatus where a circle of light could be projected on a screen, with the size of the image being controlled by a lens connected to a dial. Children in his studies turned the dial to adjust the size of the projected image. They were told to match projected light to the size of various circular objects they were given to handle. First he asked children to match various grey circles ranging in diameter from about half an inch to an inch and a quarter. On the whole, this was an easy task, with only a slight tendency to overestimate the size of the largest disks. But when subjects were asked to estimate the sizes of various coins – from a dime through a fifty-cent piece – noticeable systematic distortions emerged. Of course the coins were exactly the same as the grey disks whose sizes were correctly judged before. But something new had been introduced. There was across-the-board exaggeration. The penny was seen as larger than the gray disk of the same dimensions. The distortion was even greater for the dime. The fifty-cent piece was consistently and substantially enlarged. Children from the poorer neighborhood of Roxbury in central Boston simply saw all the money as being larger than did the children from the relatively better off suburb of Cambridge (Bruner and Goodman 1947). Bruner’s observation that perception is a matter of personal, value-based interpretation (Bruner 1957; 1958) has been replicated so often now that no manuscript showing this effect would be worthy of publication. This is also consistent with common experience. Running one’s tongue across the space where a tooth has been extracted can give the impression of a gap of huge size. When I returned at age 60 to the house I grew up in I was struck by how small the front yard seemed. Being assigned to mow it as a child seemed like a life sentence to hard labor. There is an even deeper lesson in Bruner’s little demonstration. In the discussion section of the paper where this study was reported, Bruner made a big deal over the fact that there was no verbal or conceptual dimension in the children’s assessments of size. In fact, children were never asked to say how big the disks and coins were. Perception led to action, with an uncertain role for possibly intervening rational processing. It may well be the case that much of our moral behavior never reaches the rational level of abstraction. It would be possible to give several different equally correct and apt answers to the question: “What is the diameter of a quarter?” That is a different matter from assessing its value. There are undoubtedly a few people (perhaps those who collect coins or work in mints) who know the answer to that question. It might be possible to find this kind of information through an Internet search. Coins can actually be measured, although that opens the door to debates about tolerances in measurement. Each of these approaches is aimed at a different question from how large the coin appears to be. Framing is about how our patterns of perceptions point toward behavior, not about accurate descriptions. Immediate There really is such a thing as love at first sight. Modifying the cliché conveys the real message: what we see determines our immediate reactions. Later, based on additional impressions that are immediate at that time, we may feel like reassessing our first impressions. But we are talking about two different things: the immediate impression that we are swept off our feet and the later immediate perception that we might have been hasty. Both impressions are immediate and face valid – we have no reason at each moment to feel differently. In both cases we have evidence in hand that might make us do one thing or another to bring about a world we would prefer to live in. When we sense something in the world we engage some of a variety of brain functions. Sometimes we trigger a habitual direct path from stimulation to response that has survival value but very little insight. We duck before we realize that it is whiffle-ball. Other times we engage in intricate patching together of bits of interpretation from multiple centers and end by taking no action at all. We may even irretrievable forget the experience within moments. Changing our mind is not an argument against immediacy. We replace one immediate sense of the situation with another. In fact, it takes a little bit to create that third sensing called “changing our mind.” Brain research finds patterns indicating that a decision had been reached exist and remain unchanged for up to 10 seconds prior to our being aware that we have reached a decision (Pronin 2006). We are well into our moral position before we sense that we are being confronted with this kind of challenge – if, in fact, we ever do become aware of it. We can “know” something in both an immediate sort of way and as a rational conclusion. Consider the famous Müller-Lyer illusion. Figure 7.2: Müller-Lyer illusion. Everyone “knows” that the two horizontal lines are the same length despite the fact that we sense the top one as being longer. It is not an error to perceive the lower line as shorter. That is the way we see it. We also sense the figure on the top as having “fins” that flare outward. But if we were to look at the image on our retina we would discover that the out-flaring fins are on the bottom figure. We naturally see the world “upside down” but interpret it as “right-side up” – whatever that means. We do not first see the world and then interpret it; first we interpret the world and then we realize that we have seen it. We see immediately and in context. Distorted familiar faces are more grotesque and frightening than are the same features randomly arranged. Repeated background sounds just disappear. The same word, such as “constitutional,” becomes nonsense when repeated at length or heard out of context. We “know” when someone is not telling the truth and we know how to drive a car or tie a four-in-hand neck tie without being able to say much meaningful about it. No one can define the words “of,” “about,” or “sake” (we revert to giving examples), even though we sense right away when they are used improperly. It is perfectly possible to both sense our situation in the world and to sense something about that. These can even be in conflict. For example, we sense that the upper horizontal line in the Müller-Lyer illusion is longer while we know that they are the same. We can even entertain a third, superordinate notion that we are clever enough to manage both impressions. 8 The point about seeing an object in one context being different from seeing the same object in a different context can be illustrated by the famous Pigeon Poop on the Window Demonstration. Locate a smudge on a window nearby (or put up a piece of Scotch Tape). Move your head so that the smudge appears against a very light background – the sky or a tan building -- and you will notice that the smudge becomes slightly darker. Now move your head so the same smudge appears against a darker background, perhaps a tree in the shade. The smudge gets lighter. Cut a small hole in a piece of paper that tightly surrounds the smudge and repeat the experiment. You will observe that the background shift effect disappears. The smudge becomes its own context. Academic philosophers create elaborate theoretical scaffoldings around ethical issues to accomplish something like this “objectifying” effect. If we can take an issue out of context we can accomplish wonderful transformations. That is exactly what happens in singleissue, best principle ethical arguments. That is the Principle Problem. Many people do literally walk around with blinders that restrict their framing of the world and are proud to do so. Incidentally, for those who think that reason is somehow more veridical than sensing, I must mention that the lower horizontal line in the Müller-Lyer illusion above actually is physically longer than the upper one. Putting a ruler on the lines will confirm this. This will serve to demonstrate that “objectivity” is a secondary process that we have to manufacture. Reason is fallible in just the same way that sensing is because reasoning is internal sensing. It is one pattern in the brain integrating various other patterns that already exist in the brain. That is what it meant to “know” that the lines in the illusion are (supposed to be) equal. Value-laden Sensing comes fully equipped with custom-fitted values. Thoughts do not start as objects with hooks that pick up meaning as they go. We think too fast for that to be the case. If we want our perceptions of the world to be neutral or to take on some conditional perspective, we have to pay extra to have the values removed. We do not really see values; we see through them. Those aspects of the world that have no value to us literally become invisible. Consider the famous case of the frog and the fly. A fly can sit near-by and quietly in full frontal view of the frog without danger. Insects become vulnerable when they move because the frog’s visual system is acutely tuned to detect motion and rather dull at identifying shapes. Similarly dogs see better in the dark than we humans do because they have only rods in their retinas. They are color blind. In both cases the chances of seeing what is valued are increased over the chance of seeing what matters little. All sensing is about recognizing what has value for us. Here is a demonstration you can perform now. We normally have an intuitive sense of what time of day it is. Often we can guess the correct time to within 15 or 20 minutes. We consult a watch only when being more accurate matters, and it would be considered a nervous tick to glance at it several times each minute. But even then we realize that watches are not always exactly exact. Try the experiment now. Make a judgment about the current time to within one minute. Now check your watch to see how well you did. Well? Most people are off by a few minutes. But the order of magnitude of the discrepancy is almost never enough to make any difference or cause any change in one’s behavior. (To be perfectly honest, I do not do these silly little exercises either when other authors ask me to. But in this case, no one gets a pass. Consistent with principles of framing, there is no way you can avoid participation unless you skip reading the next paragraph.) Now the real purpose of this exercise had nothing to do with the current time: that will surely change. What I was really interested in was your sense of the numbers 2 and 3 on the face of your watch. You have just seen them (or certainly you have done so in the past). But can you say for certain whether they are Arabic or Roman numerals or some other symbol such as a dot or square? Are both of them the same? Are they black, gold, silver, or some other color? We see what we are looking for or what our training tells us we need to see for our own good at this very moment. The rest is there but only as part of the context. If it is really the case that sensing is about monitoring the world for threats to our survival, we should have greater acuity for situations that challenge us than for opportunities. Up to a certain point, that is true. We do monitor on the “danger” channel a bit more closely than on the “get ahead” one. This matters when ordering elements in the moral framing matrix. In rational theory, the half-way point between a 50:50 chance of winning $5,000 and losing $5,000 is zero. In practicality we shade matters to give ourselves a buffer. The exchange rate between gains and losses is actually estimated to be something like 1 to 2.25 (Kahneman 2011; Kahneman and Tversky 1979). Most people would not accept and even-money wager. They want slightly more than $11,000 for winning to make it worth risking a loss of $5,000. The rank orderings of moral engagement matrices is fairly robust because we deal in ranks, not absolute numbers. But this is a source of distortion one should be aware of, especially when trying to equate my gains with your losses. For years, psychologists have been trying to catch folks in the act of seeing something (Godnig 2003). One common methodology is to project combinations of letters that resemble words on a screen for a fraction of a second. When subjects wrote down what they thought they saw, they seldom reported combinations of individual letters. They “saw” words, and the words they saw revealed something about who they were. Nurses see CARF as the word “care.” Investment bankers see “PORFT” as “profit.” Individuals who have been instructed to fast before the study see HANBERPER as something to eat more often than did subjects who are well-fed. When combinations of letters that might be mistaken for nasty words were shown, some subject just will not go there. INTRCCRSE became “increase” or “of course” instead of one of the accepted term for sexual relations. Persons with strong political or religious leanings are simply less able to see stimuli that challenged their view of the world. Jonathan Haidt (2012, 64) summarizes: “Brains evaluate everything in terms of potential threat or benefit to the self, and then adjust behavior to get more to the good stuff and less of the bad.” Jean Decety and her colleagues study how fast we sense values (2010). A typical investigation includes monitoring the electrical impulses in various regions of the brain as subjects watch potentially anxiety-provoking events. Photographs of people being pricked with a needle in the foot, the hand, and the mouth are examples. Decety used event-related potentials from electrodes place on the scalps of participants to record extremely precise time lapses between seeing the painful images and reactions in various parts of the brain. P3 in the centroparietal region of the middle part of the cerebral cortex is involved with integrating sensory information with bits of data from other centers. It is cognitive in the sense of reflecting multiple secondary data. N110 is in the frontal cortex and is involved with emotional responses. It will come as no surprise to learn that individuals looking at photographs of people being pricked with needle in sensitive areas, compared with similar photographs showing a Q-tip resting on the skin, caused very measurable neural responses in relevant regions of the brain. But it might not have been anticipated that the peak emotional response in the frontal region occurred three times as quickly as the peak cognitive response in the brain region where subjects tried to interpret and “understand” what was happening. Of course, it was almost instantaneous in both cases: a fifteenth of a second for the emotions and four-tenths of a second for the cognitive response. But the message is very clear. We do not form emotions in cases like this based on our interpretation of the situation. It seems to go the other way. Decety had one more card to play. Some of her subjects were physicians and some were not. And there was a difference. Physicians were significantly less likely to register a response in the emotional frontal region. But their activity in the integrative or cognitive center was as sensitive, or perhaps even a bit more so, than were the non-physicians. It seems there is a neurological justification for the distinction sometimes made between sympathy and empathy. The first term is properly used to designate mirroring or “feeling like” others. Empathy means knowing or understanding or projecting the consequences of what others might be feeling. RMA is based in the latter capacity. And we will find out shortly that the temperoperital region of the brain where the ability to project what others might expect their actions to achieve may very well play a critical role in moral behavior. Future Orientation In his essay “On Self-Sufficiency,” Ralph Waldo Emerson (1841/2000, 142) said that “perception is not whimsical, but fatal.” He was not talking, however, about the Old Testament fear of being struck dead at the sight of the Almighty. Emerson was just noting that we tend to go in the direction we are facing. We become our vision of the future. Daniel Dennett (1991, 177) remarked that “the fundamental purpose of brains is to produce future.” Sensing makes us lean forward: our current perceptions prefigure what is next. If this were not the case, one of the great problems of philosophy would have to be how we keep going. Why do we not just stop after solving an ethical issue the same way journal articles do. Just as values are a natural dimension of neural events, so is conation. Sensing motivates us to action. We do not so much see things as they are; we sense the gap between what is and what could be. We carry around our plan for how to make the world better, constantly using it as a guide and forever tweaking it. That is why we are horrified by dislocations, eager about potentialities, and overlook the unexpected. If this were not so, our brains would seize up and become bloated and useless at an early age. When we sense the world we also sense whether it can be safely ignored or whether a change might be advantageous to us and others. Roderick Firth used to tell his philosophy students at Harvard that we cannot know anything at all about a book with no color, shape, or weight: all books came preloaded with these attributes. Conceptually that was a sound thing for Firth to say in a philosophy course: it makes no sense in a psychology course or in the practical world. To make it easier to handle, let’s change the object of our concern from a book to a playing card. Select one from a deck, being careful to see only the back of the card that has a common pattern for the whole deck. Hold it at arm’s length and eye level as far as possible to the right. Carefully turn the card over so that the face would be visible to you if it were immediately in front of you. Look steadily, eyes-front, during the entire process. At first, of course, you will not be able to see that there is anything at all to your right or left. Slowly move your hand a few inches toward the front. Eventually you will be able to see that there is “something” approaching from that direction. As the process continues, you will register some information about the size of the object. Sophisticated subjects will about this point “see” the object as moving. Next, color appears since we do not have color vision at the periphery, regardless of what we might think. Next you will see whether or not you have a face card or something else approximately the same size. Finally, you can identify the card. You will be surprised at how narrow the visual field is. If we could register this in the brain, we would see that different regions participated at various stages in the process. It is not perception; it is perceptions that become integrated into larger replacement perceptions. 9 The more important lesson is that Firth was only right about the “concept” of a book, but he was wrong about the perception of actual books. The way we talk about ethical concepts may be a shaky guide to how people make moral sense of their worlds. Few people are morally “bad,” but far too many are morally “blind.” Nothing happens when we scan our world and conclude that there are no potentials for making improvements. In fact, we soon enough turn off our sensing equipment. Sensing and Reasoning This chapter is about sensing – the immediate, future-oriented blending of cognition, valuation, and conation. There is a great and silly debate in philosophy over whether reason or the passions governs morality. 10 Immanuel Kant was the champion of the rational crowd: “The ground of obligation must be looked for, not in the nature either of man nor in the circumstances of the world in which he is placed, but solely a priori [independent of the facts of the matter] in the concepts of pure reason.” In the other corner, wearing the empirical trunks, was David Hume: “Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.” Some modern philosophers try to excuse the confrontation with terminological gestures. Kant, it may be plausible to hold, had a theory of pure reason that manages abstract ethics in a transcendental world and a theory of practical reason for actual behavior. Hume, the peacemakers say, granted an instrumental role to reason – it helps the passions find ways of doing what the passions want, presumably by blocking impractical passions. But at the beginning of the final book of his Treatise on Human Nature, Hume is pretty blunt in saying that “the rules of morality are not conclusions of our reason.” 11 The real issue, as Hilary Putnam (1981) points out, is who has the last word. Does reason sit in judgment of the passions, or is it the other way around? And of course, how foolish to think that the “last word” is anything other than the place we stop worrying about a particular moral engagement and start thinking about something else. It is very difficult to make a compelling case for the passions when they are equated with emotions. Emotions, which are largely mediated by hormones, are slow and broad acting. And they are cognitively ambiguous. A queasy feeling in the stomach, light-headedness, an elevated heart rate, and other autonomic nervous system responses, could be any of several things from anxiety, to fear, to infatuation, or a stomach ache. Children learn to distinguish illness from embarrassment based on the way adults react to them and the circumstances, not on how they feel. Hume would likely be unimpressed with that argument. He does not equate the passions with emotions. 12 A better twenty-first century translation is “values,” or even “affect” or a term Hume himself favored “sentiment.” In Book II of the Treatise, where Hume develops his concept of the passions, he notes they are “simple impressions” that the “mind gives itself.” They are internal sensing. The other simple impressions given the mind are ideas, the stuff of cognition. Earlier in this chapter, I probed the notion that the sense we take of the world, our moment-to-moment framing of it, comes equipped with values as well as rational content. It also naturally expresses itself in conation or “go/no-go” action triggers. It could be that Hume and Kant each have part of the puzzle. What actually happens in moral brain processing, there is reason to believe, is that senses from the external world are combined with stored impressions in working memory in the prefrontal region. A thought may involve dozens of internal sensing slices where the brain shows itself value-laden internal and external senses, keeping only the residual internal reframing. That is why thinking takes orders of magnitude longer than perceiving. The mistake of eighteenth century theorizing about passion and reason was to conflate the value-rich mental images that drives our behavior with the value-rich mental images we later have of the first images. Seeing Together The way we frame the world comes preloaded with values. We are hardly indifferent to the way things seem. What matters little is little noticed. This is a blow to realist theories of ethics that are based on assumptions of an external objectivity. 13 Values work their way into moral choice even before we have an opportunity to make rational calculations. Now we must consider the possibility that our value-drenched perceptions of reality are not even entirely our own. They might be social constructs. We are more than interested in the way the world seems to others. Let’s go back to the psychology department at Columbia University in the early 1930s and follow the work of a Turkish-American doctoral student, Muzafer Sherif. He built a room capable of being completely darkened, with a screen on which was projected a dot of light for a period of several seconds. His subjects sat at a table facing the screen and were shown a series of 100 projected light spots. After each projection, subjects were asked to report out load how far the light spot had appeared to move during the two seconds it appeared. Subjects reported their estimates in inches, with ten being the usual upper limit and three or four inches the most typical reports. Sometimes, a single subject was tested, sometimes either two or three were tested together, but each subject reported his or her estimates audibly, independently, and in random order. Here is what Sherif reported (1936). Single subjects used a range at the beginning but converged on a personal standard as the trials progressed. Subjects tested in groups did the same, but they converged on a group norm. When subjects were tested individually a week after working in the group setting, they retained the group standard. The point is simple and clear (and is still regarded as a valid psychological generalization): we create standards for perceiving ambiguous phenomena, and when they are available, we contribute to and borrow from the standards of others. Perception is a socially normed process. Now it does not really matter that the spot of light never moved at all in Sherif’s study. The “objective” answer would have been zero in all cases. That is just not the way the autokinetic effect works. The brain in its most stable state of rest is engaged in constant random firing. Mental diseases such as schizophrenia are associated with abnormal suspension of random autogenerated activity. Objectivity can make us sick. It might be fair to say that the default mode is to perceive relationships rather than to create them (Csikszentmihalyi 1994). Sherif’s work highlights the natural neural mechanisms that are the spontaneously generated background of precognition. The Belgian psychologist Albert Michotte (1946/1963) demonstrated that even children spontaneously attribute “causality” to blobs of light that seem to be bouncing off each other. This is a matter of sensing rather than reasoning. Initially, Sherif was criticized for “misleading” his subjects and especially for using shills to create false consensus. There were no confederates – each subject was both his and her neighbor’s context and the beneficiary of input used to create a common standard. Sheriff summarized it this way: “When the external surroundings lack stable, orderly reference points, the individuals caught in the ensuing experience of uncertainly mutually contribute to each other a mode of orderliness to establish their own orderly pattern” (Sherif, xii-xiii). Point of View: Point-blank Thinking Hunting for ideas should be done at very close range. Having thoughts is not exactly like having credit card debt or potted plants on the path leading to one’s front porch. When we die, something has to be done about our potted plants, but not about our thoughts. It is almost as though our thoughts are nothing more than patterns in a living being. It is commonly “thought” that folks have many thoughts. But I do not see how that could possibly be true. We only have one: the one currently “in our head.” When we are finished with this one, we get a new one. Every new thought pushes the previous one aside. 14 But we certainly have memories of thoughts -- uncountable multitudes of them. It turns out that is also a bit problematic because our memories are only potential and many of them are hopelessly unrecoverable. When we were four years and 58 days old we had a little journey from our bedroom to the bathroom. Last Thursday we plotted a strategy for escaping a tiresome conversation with somebody who was using up our time. We may be able to get the recollection of these things back from their neurological hiding places, but it is a safe guess that they are 100% useless baggage. I am surprised Franz Kafka did not write a story about a traveling salesman condemned to remember the room number of every hotel room he stayed in or the number of every phone call he had made. What we call forgetting is our friend. But it is not really making memories disappear that is so valuable; it is not having to pay attention to them right now that makes us effective. PTSD and neurosis and psychosis are one-time necessary neural patterns that no longer work but must be endlessly repeated without being reshaped to current needs. A memory we cannot recover has no more existence than an event that has not yet occurred. The tip of the tongue phenomenon is not a memory at all – it is a present thought about an unavailable memory. My capacity to respond here and now is only my total set of thoughts, memories, emotions, and opportunities here and now. A memory only exists now. When I think a little bit, I create new memories by rearranging the neurons in my brain. When I come back to reconsider that situation, I have the potential for incorporating that stored residue of my previous work into my new understanding. Daniel Dennett (1991) calls this the “working draft” theory of the brain. In order to give this concept a handle so it can be carried around more easily, I will call it “point-blank thinking.” The term is John Dewey’s (1929), used in his 1925 Paul Carus Lectures. One brain pattern at a time, different brain patterns replacing each other in succession, perhaps incorporating bits of previous brain patterns. Think of thinking as folding a piece of paper, as in origami: same paper, different objects. All of this is done hands-on and at very close range. In fact there are no wireless connections. Neural transmission is managed by electrochemical ion exchange at synapses. 15 The gradients have both excitatory and inhibitory potentials and usually no one-to-one relationship. For example, the near simultaneous stimulation of a dendrite by several adjacent nerves may be required for activation. Regions or circuits in the brain are not separate organs (as the liver and heart are) so much as patterns of neurons defined by the connections among their neurons. A circuit is a pattern with high potential for interaction. Many neurons have very short connections, only affecting very near neighbors where the combination of excitations determines activity. This is especially true in the prefrontal cortex where working memory takes place. All brain regions also have a few long distance neurons that provide input from remote regions that bring in different kinds of information. 16 Myelin is a membranous sheath surrounding the axons of mature neurons. Although neurons may be present, some of them function poorly without being myelinated. Important regions in the prefrontal cortex, for example do not myelinate until about age four in humans and there is a second period of myelination in adolescence. Neural activation is also mediated by hormones that temporarily fill spaces surrounding neurons and either promote or retard activity. The hormones (associated in the common understanding with emotions) are released by glands that have been stimulated by electro-chemical impulses from nerves, and they arrive in the blood. Because hormones are relatively slow and long acting and generally regionrather than neuron-specific they act as a secondary cycle in brain functioning. 17 This is three-way weird. First, it all happens so quickly that we are unaware of the process. We feel resistance and fatigue from yard work, but no one has ever “felt” a thought. 18 Several thoughts can succeed each other in fractions of a second. In the time needed to read the preceding eleven-word declarative sentence, readers will have had many thoughts, not all of them related to the topic under discussion. Second, our brain does not match internal and external representations. The example of the Necker cube shows that we use bits and pieces and fill in only as much as is needed to get on with our work. The TV character Monk is lovably laughable because he is pathologically incapable of stopping the recognition process at anything like a proper point. The brain of everyone but Monk is only interested in achieving “good enough.” 19 The third reason we just never think of thinking as a process of rapid replacement of cheap approximations is that from about age four, we can have thoughts about thoughts. It is something like knitting. Past thought provide the structure for current ones, even becoming updated elements in what we are now thinking. I have defined a thought as a pattern of neural synapses with the potential for influencing future action, including creating new patterns of neural synapses. But a thought is not a definition. The definition is “about” the thought; it is an enriched potential replacement. Both the thought and the thought about the thought are different point blank neurological experiences and they likely take place in different parts of the brain. The most tragic error in both daily life and in philosophy is to mistake the replacement for the original. We can think about unicorns in the sense of patching together a bit of our memories of horses with a remnant of narwhales or such, seasoned with Romance literature from the Middle Ages, all moshed together into a current fantasy. But we cannot feed unicorns. Unicorns are not real: thoughts about unicorns are. Universals do not exist, although the idea that universals might be nice to have when needed is certainly something that has been talked about on occasion (Quine 1981, 182). I just do not see how two people could have the same thought, except in some metaphoric sense. If they did and no one knew about it that would be unremarkable. If a third party, or one of those involved in reflection, entertained the notion of two people with the same thought, that would only be one new thought and perhaps neither of those with the same thought would care much about it. “Same,” of course, means “close enough that we need not be concerned about differences.” That pragmatic criterion works most of the time for one person at one time. We need to allow for people changing their minds and for one person saying this is “the same” for you but not for me. Most philosophers today think that Descartes was confused in equating the “I” that thinks with the “I” that is thought about in his cogito -- “Je pense donc je suis.” That is two too many je’s: one that does the pense-ing, one for suis-ing, and one for those who are interested in these sorts of statements. It is immediately obvious that this could get out of hand. The fix has been to posit an “I” that does the thinking and call all the rest attributes of that “I.” I am a subject and I have predicates. That has worked fair to middling as long as we honor the agreement that an “I” without predicates is unimaginable. (But we immediately violate the cease fire because “unimaginable” is in fact a predicate.) In polite company, we know better than to discuss politics, religion, or the difference between your “I” and mine. Ethics is too often said to be a personal matter because that is the way “I” see it. Naturalists can wiggle out of this pickle, and not in a fashion that makes them easy targets for normativists. Of course the mind and the brain are not the same thing any more than a unicorn and a charmed, white horse with a horn on its head are. There is no neural circuit for morality. There is no truth filter in the brain. There is not even a cell for the correct spelling of Nietzsche. Having peace of mind does not mean that some part of me has something that people may wish they had. It would be futile to do fMRI scans to see what part of the brain constituted the “peace” center. It is a pattern of the whole person. A smile is a configuration involving facial features; a scowl is an alternative configuration of the same facial structures. If I disappear, so does my smile, Lewis Carrol’s Cheshire cat notwithstanding. In exactly this way, a thought is an arrangement of neurons, chemicals, muscles, and more. Replacing the thought, or adding an emotion to a thought, just means rearranging these in a different pattern. 20 With a thousand billion neurons in the human brain, give or take, there would be enough permutations to capture all previous configurations in rolling successions of new patterns. Of course some thoughts or emotions or volitions are impossible because there is no way for the current equipment to form the proper pattern. Kant was right on that score. For example, until certain regions of the prefrontal cortex myelinate at around age four, children cannot form any pattern that others would identify with conditional reasoning. Kant was correct that dogs cannot be ethical, although we can treat them morally or otherwise (Menzel and Fischer 2011). 1 A staple of pop training sessions in recent years is having participants watch a video of folks playing basketball while engaged in a mindful task such as counting the number of times the ball is passed. An actor in a gorilla suit walks through the image but is missed by most who are counting. Trafton Drew and his Harvard colleagues carried this to a dangerous extreme. They inserted cartoons of gorillas on radiographs of lungs. The fact that radiologists read the diagnostic images were regularly oblivious to this unexpected change in the makes one wonder what else they are missing (Drew, Võ, and Wolfe 2013). 2 Gilbert Ryle (1949) is the great philosopher of the category error: thinking that giving something a name at one level explains the phenomenon at a different level. His example was of watching with great interest as the marching bands, men in formation, and displays of arms pass in review but wondering when the parade would start. Much of the futility of religious debates stems from category errors. 3 We notoriously exaggerate the extent to which what is obvious to us is apparent to others. Elizabeth Newton’s 1990 doctoral dissertation at Stanford illustrates the point. She gave subjects slips of paper with the names of various familiar tunes and explained that the subjects should tap the rhythm of each with his or her fingers on a table and so colleagues could try to guess the tune. These were all very common ditties such as “Yankee Doodle” and “The Star Spangled Banner.” Estimated average success was 36%; average actual success was 2%. 4 I follow Werner Heisenberg’s Philosophical Problems of Quantum Physics (1952) and Erwin Schrödinger’s What Is Life? (1967) in my presentation of how science knows the material world. 5 The story of Heinz and the research literature on Kohlberg’s Kantian theory of moral development can be found in Reimer, Paiolitto, and Hersh (1983) and the research on its impact is well summarized in two anthologies edited by James Rest and his colleagues (1995; 1999). 6 Rest summarizes a strong body of literature that professionals score higher on the Defining Issues Test than do non-professionals. In a paper by Kohlberg and Candee read at the Florida International University Conference on Moral Development in 1981 evidence was presented that individuals who participated in student protests or terminated participation in the Milgrom studies on “torture” scored higher on Kohlberg’s moral development scale. What is missing is the evidence that individuals use higher ethical skills in performing specific moral acts. 7 There are no population-based studies of “typical” moral functioning levels. Most of the work has been done with subsamples, such as nurses or seminary students, who are thought to be more likely to engage in principled ethical reasoning (Gibbs 1979; Snarey 1985). Kohlberg himself dropped level 6 from his system and most commentators find the prevalence of the top two – principled – levels too small to merit study (Modgil and Mogdil 1986). 8 William of Ockham pointed out pretty clearly the difference between sensing and judging in the fourteenth century (1957), but we keep forgetting about that. 9 The sequentially emerging recognition of a physical object is more than empiricism; it is neurophysiology (Anastasios 2009). The visual cortex at the back of the brain is divided into six regions. “Object” identification takes place in a process of iterative filtering through regions. Each cortical layer is tuned to sort for specific features and then pass on reinterpreted “objects” as patterns to the next level where the previous pattern, not the “object” is further filtered. We literally serially construct “things” rather than seeing them. For example the primary visual cortex (V1) only picks out boundaries. V2 has a ventral branch to the amygdala and motor system. That is why we are able to duck to avoid being hit by a flying object before we know what the object is. V3 is an integration area, registering motion and sending messages back to V1 for clarification. Further integration, including input from other regions of the brain takes place at levels 4 through 6. The “finished,” successively augmented product is passed on, as a pattern of nerve firing, for various other regions in the brain to work with. When the involved nerves stop firing the previous version of the “object” no longer exists. This modern view is surprisingly similar to the one proposed a century ago by William James (1890/1950) who suggested that perception is the selection of meaningful parts of the continuous stream of consciousness which he called a “blooming, buzzing confusion.” 10 Kant’s rational position is found in the preface to his Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785/1948) and Hume’s famous passionate defense of the passions in in Book II, Section 3 of his Treatise of Human Nature (1739/1960). 11 The view that reasons come first and drive ethical behavior can be found among the following: Thomas Nagel (1986) and Christine Korsgaard (1996). Bernard Williams (1972) and Derek Parfit (1984) are also usually read this way. 12 Simon Blackburn, in his How to Read Hume (2008), gives us an interpretation of Hume that protects against unfair characterization of “passions.” 13 Moral realism is defended by, among others, Peter Railton (1986), Richard Boyd (1988), Jean Hampton (1996), and Russ Shafer-Landau (2003). Broadly, the idea is that there are objective ethical truths existing independent of what anyone thinks these truths might be. We are wrong whether we know it or not. My one-line response is “Who knows that?” 14 Oscar Wilde (1948) has a wonderful little poem-in-prose story, “The Artist,” about a sculptor who wants to create a status called the “Pleasure that abideth for a moment.” The only bronze available, and what he must melt down and replace is his own work called “The sorrow that endureth forever.” 15 In note 8, I explained how patterns of neural firing are modified and passed in a fraction of a second through the six layers of the visual cortices. This sequence of patterns that change subsequent patterns like a wave approaching the shore is completely generalizable for all cognitive, emotional, and volitional activities of the brain. See LeDoux (1996; 2003), Weyhenmeyer and Gallman (2007), Chakravarthy Joseph, and Bapi (2010), and Stocco, Lebiere, and Anderson (2010). 16 There is an important analogue between the structure of tightly packed and collectively interacting neurons in a brain region with interspersed long-reach messenger neurons connecting to other regions and the theory of complex systems “small world” structures (Watts and Strogatz, 1998). 17 In addition to LeDoux and Dennett on point blank mental processing, see the work of Jorgen Weibull (1995), Greenwald, McGhee, and Schwartz (1998), Patricia Churchman (2011), and Daniel Kahneman (2011). Wilfrid Sellars (1956/1963, 180) is direct to the point: “The thought we analyze is not the thought that does the analyzing.” 18 The famous logical positivist, Moritz Schlick, made much the same point about not being able to “feel” our thoughts. We can only experience them: “Thus I can only feel pleasure and pain, I cannot think or imagine them. . . . Moreover, one cannot imagine an idea, but can only have it. . . . For every idea presupposes some perception as its pattern” (1939, 71). 19 See Jeffrey Schwartz and Sharon Begley’s (2002) treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder for a detailed analysis of what happens when the brain cannot stop itself from thinking and how the brain can be thought of as reprogramming itself based on experience. 20 Radu Bogdan, in Our Own Minds: Sociocultural Grounds for Self-consciousness, (2010) comes close to the view I am expressing in terms of the cognitive-evaluative-volitional complex as a pattern. So does the impish and intriguing Douglas Hofstadter, in Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (1979), I Am a Strange Loop (2007), and The Mind’s I: Fantasies and Reflections on Self and Soul (1981) which he edited with Daniel Dennett.