Chapter 2 Outline Notes

advertisement

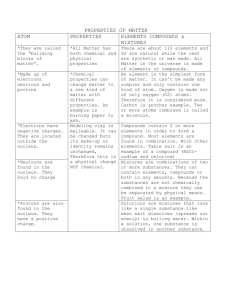

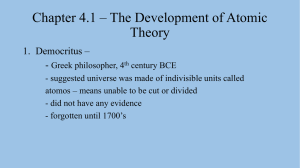

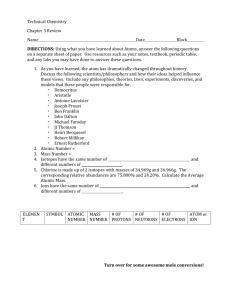

WHS AP Chemistry Chapter 2—Atoms, Molecules, and Ions Instructors Notes I. The Atomic Theory and the Structure of the Atom a. Democritus i. All matter consists of very small, indivisible particles, which he named atomos b. Lavoisier i. Law of conservation of mass—matter can be neither created nor destroyed c. Proust i. Law of definite proportions—different samples of the same compound always contain its constituent elements in the same proportion by mass d. Dalton i. Proposed an “atomic theory” composed of four hypotheses detailing spherical solid atoms based upon measurable properties of mass • Elements are composed of extremely small particles called atoms • All atoms of a given element are identical, having the same size, mass, and chemical • • e. f. g. h. properties. Atoms of one element are different from the atoms of all other elements Compounds are composed of atoms of more than one element. In any compound, the ratio of the numbers of atoms of any two of the elements present is either an integer or a simple fraction. A chemical reaction involves only the separation, combination, or rearrangement of atoms; it does not result in their creation or destruction. 1. Law of multiple proportions—if two elements can combine to form more than one compound, the masses of one element that combine with a fixed mass of the other element are in ratios of small whole numbers ii. Atom— basic unit of an element that can enter into a chemical combination Radiation—the emission and transmission of energy through space in the form of waves i. Cathode ray tube 1. Electron—negatively charged particle ii. X-rays iii. Radioactivity—spontaneous emission of particles and/or radiation iv. Radioactive—any element that spontaneously emits radiation(shows signs of radioactivity) v. Decay—radiation that comes from the breakdown of a radioactive substance Rutherford 1. Alpha (𝛼) ray—positively charged particles (𝛼 particles) after 2. Beta (𝛽) ray—electrons (𝛽 particles) Thomson 3. Gamma (𝛾) ray—high-energy rays J.J. Thomson i. Charge (coulomb) to mass ratio of an electron: −1.76×108 C/g ii. “Plum-pudding” model—an atom could be thought of as a uniform, positive sphere of matter in which electrons are embedded R.A. Millikan i. Millikan Oil Drop 1. Electron charge: −1.6022×10−19 C 2. Mass of an electron: 9.10×10−28 g Rutherford—the atom is mainly made of empty space, with a small concentrated positive mass in the middle (didn't tell us anything about the arrangement of electrons) i. Gold Foil Experiment ii. Nucleus—dense central core of the atom iii. Proton—positively charged particles in the nucleus 1. Charge: 1.6022×10−19 C 1 WHS AP Chemistry 2. Mass: 1.67262×10−24 g i. Moseley—atomic number is equal to the number of protons j. Bohr—atom built up of successive orbital shells of electrons (only worked w/hydrogen) k. Schrö dinger—viewed electrons as continuous clouds i. Quantum Mechanical Model l. Chadwick (since He has 2 protons and H has one, the mass ratio should be 2:1 but it’s 4:1) Mass number i. Neutron—electrically neutral particles 𝐴 X II. Atomic Number, Mass Number, and Isotopes 𝑍 atomic number a. Atomic number (Z)—the number of protons in the nucleus b. Mass number (A)—total number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus of an atom c. Isotopes—atoms that have the same atomic number but different mass numbers due to a different number of neutrons i. Ex. 235 U (uranium—235) and 238 U (uranium—238) 92 92 III. The Periodic Table—chart where elements of similar physical and chemical properties are grouped together; modern periodic table is grouped by atomic number a. Period—horizontal row b. Group/family—vertical column i. Alkali metals (group 1A) ii. Alkaline earth metals (group 2A) iii. Halogens (group 7A) iv. Noble gas (group 8A) c. Metal—good conductor of heat and electricity d. Nonmetal—poor conductor of heat and electricity e. Metalloid—properties that are intermediate between those of metals and nonmetals IV. Molecules and Ions a. Molecule—an aggregate of at least two atoms in a definite arrangement held together by chemical forces (atoms can be the same or different; electrically neutral) i. Diatomic molecule—contains only two atoms (atoms can be the same or different; ex. O2 or HCl, NO, CO) ii. Polyatomic molecule—more than two atoms (atoms can be the same or different; ex. O3 or H2O, NH3, NO2, CO2) b. Compound—two or more elements chemically united in fixed proportions (all compounds are molecules, but not all molecules are compounds) i. Molecular compound—made of atoms from two or more different elements (nonmetals) held together by covalent bonds (sharing of electrons) 1. Binary molecular compound—two atoms from different elements held together in fixed proportions by covalent bonds ii. Ionic compound—two or more elements (metal/nonmetal) held together by ionic bonds (transfer of electrons) 1. Ion—atom (group of atoms) that has a net positive or negative charge (number of protons remains the same, charge = loss or gain of electrons) a. Cation—ion with a net positive charge due to the loss of one or more electrons from a neutral atom b. Anion—ion whose net charge is negative due to an increase in the number of electrons from a neutral atom c. Monatomic ion—contain only one atom d. Polyatomic ion—ions containing more than one atom (charged molecular compound) 2 WHS AP Chemistry V. Chemical Formulas—expresses the composition of molecules and ionic compounds in terms of chemical symbols a. Molecular formula—shows the exact number of atoms of each element in the smallest unit of a substance i. Allotrope—one of two or more distinct forms of an element b. Empirical formula—tells us which elements are present and the simplest whole-number ratio of their atoms i. Formula of ionic compounds—usually the same as their empirical formulas; formula unit (smallest whole number ratio of cation to anion 1. Electrically neutral— cation + anion = 0 2. Subscript of the cation is numerically equal to the charge on the anion, and the subscript of the anion is numerically equal to the charge on the cation VI. Nomenclature (naming of chemical compounds) a. Organic compounds—contains carbon usually with H, O, N, S i. Exceptions: CO, CO2, CS2, CN−, CO32−, HCO3− b. Inorganic compounds—everything else i. Ionic compounds (metal and a nonmetal) 1. Cation is named first, followed by the anion a. Monatomic cation—takes the name of the element i. Metals with more than one charge—include a roman numeral in parentheses denoting the charge 1. Old way—limited use (only 2 ions) a. “—ous” cation with smaller positive charge b. “—ic” cation with larger positive charge b. Monatomic anion—change the ending to “—ide” c. Polyatomic ions— need to be memorized ii. Binary Molecular compounds (two nonmetals) 1. Name the first element in the compound 2. Name the second element in the compound by adding “—ide” to the root 3. Add Greek prefixes to each element to denote the number of atoms present a. Exceptions: i. Omit mono for the first element ii. Double vowels iii. Compounds w/hydrogen (use common name) iii. Acids and Bases 1. Acid—substance that yields hydrogen ions (H+) when dissolved in water a. “—ide” becomes “hydro—ic acid” b. “—ate” becomes “—ic acid” c. “—ite” becomes “—ous acid” i. in sulfur compounds, add “ur” ii. in phosphorus compounds, add “or” 2. Base—substance that yields hydroxide ions (OH−) when dissolved in water a. See ionic compound nomenclature (exception: NH3 ammonia) iv. Hydrates—compounds that have a specific number of water molecules attached to them 1. First name the ionic compound 2. Use a Greek prefix to denote how many water molecules are present followed by the word hydrate 3