eugene onegin (евгений онегин) in english

advertisement

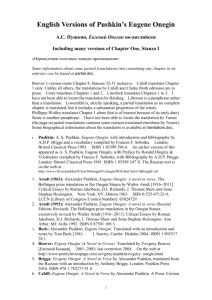

EUGENE ONEGIN (ЕВГЕНИЙ ОНЕГИН) IN ENGLISH Eugene Onegin (Евгений Онегин) is a novel written by Aleksandr Pushkin. It is, moreover, a novel in verse. As Pushkin wrote to a friend, “Я теперь пишу не роман, а роман в стихахдьявольская разница.” [“I am now writing, not a novel, but a novel in versea devil of a difference.”] The importance of Pushkin for Russian literature is, I think, very much underestimated in the West, but certainly not by Russian writers themselves. Moreover, most Russians are convinced that Eugene Onegin is Pushkin’s greatest work. It was published in serial form between 1825 and 1832. The first complete edition was published in 1833, the currently accepted version being based on the 1837 publication. The first small passage translated into English (the last seven lines of Pushkin’s dedication) was published in 1845 by Thomas Budd Shaw. But the problem of making a complete translation is made extremely difficult by the nature of the Onegin stanza, in which most of the novel is written. This consists of rhymed iambic tetrameters with a strict rhyme scheme given on the handout. It has occasionally been used in English, notably by Vikram Seth in his 1986 novel The Golden Gate; a few other examples are quoted in the handout. Translation is always difficult. As Tony Briggs in his short book on Eugene Onegin says, “no translation transmits anything to its reader beyond the basic story line and a pallid afterglow of Pushkin’s style.” Nevertheless, as quoted on the handout, Pushkin himself did write in 1830 that «Переводчики почтовые лошади просвещения» (“Translators are the post-horses of civilization”). Tetrameters are not in themselves unusual in English, although it is probably fair to say that, as Nabokov puts it, the tetrameter “has said in Russian what the pentameter has said in English and the hexameter in French.” Rhyme is more difficult in English than in Russian, the point being that Russian is a highly inflected language with a structure not unlike Latin, although with a different vocabulary (compare amo, amas, amat, amamus, amatis, amant with говорю, говориш, говорит, говорим, говорите, говорят). So the problems of translation are particularly acute in this case. Although there were a few more partial translations, the first complete translation was made by Lt-Col. Spalding in 1881. Spalding apparently learned Russian while stationed at the British Embassy in St. Petersburg. As you can see, he did write tetrameters, and he took what Briggs described as a “brave decision” to stick to masculine rhymes, so that for example the first four rhyme endings in the quoted stanza are ‘extreme / disease / esteem / sees’. Those who try to stick more closely to Pushkin’s scheme and so use feminine rhymes go for rhymes such as Elton’s ‘sickened / high / quickened / I’. But it is arguable that it is more difficult to make schemes including feminine rhymes read easily and naturally in English. I shall ignore various unimportant translations which are, however, listed on the handout. The first translator who attempted to stick strictly to the metre and rhyme of the original was Babette Deutsch (1895–1982), who was an American poet, critic, translator, and novelist. Her translation first appeared in 1936 (and was revised in 1943 and 1964). It was rapidly followed by one by Oliver Elton in 1937 (revised by Briggs in 1995). One of the three most highly praised translations sticking to the rhyme and meter, that of Walter Arndt, was published in 1963 (revised in 1992). A very important development in 1964 was the appearance of the translation by Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977), nowadays probably best known as the author of Lolita. This translation provoked an enormous controversy. Nabokov entitled one of his books Strong Opinions, and he certainly had strong opinions on translation. He states that, 1 ‘attempts to render a poem in another language fall into three categories: ‘(1) Paraphrasistic: offering a free version of the original, with omissions and additions prompted by the exigencies of form, the conventions attributed to the consumer, and the translator’s ignorance ‘(2) Lexical (or constructional): rendering the basic meaning of words (and their order) ‘(3) Literal: rendering, as closely as the associative and syntactical capacities of another language allow, the exact contextual meaning of the original. Only this is true translation.’ He goes on to say that, ‘I have always been amused by the stereotyped compliment that a reviewer pays the author of a “new translation.” He says: “It reads smoothly.” In other words, the hack who has never read the original, and does not know the language, praises an imitation as readable because easy platitudes have replaced in it the intricacies of which he is unaware.’ I think it will come as no surprise that this point of view was not shared by many reviewers. Most famously, Edmund Wilson, who had until then been a friend of Nabokov’s, wrote a stinging review in The New York Review of Books. He pointed out that Nabokov’s translation caused the reader to have recourse to the OED for English words he would never have seen and will never have occasion to use. He also took exception to the style. For what it is worth, I share many of Wilson’s opinions about the translation. But it should be clearly understood that if you want to make sense of the Russian text, Nabokov’s version is almost indispensable, being sensitive to nuances which it would be very difficult to identify from a dictionary. Among the translations that have appeared since Nabokov, one of the most highly regarded is that by Sir Charles Johnston, a professional diplomat. Johnston, like Arndt before him, tries to preserve the rhyme and meter, in defiance of Nabokov. It will be found that (at least before 1995) many authorities recommending a translation tend to recommend either that of Arndt or that of Johnston. But Johnston’s was by no means the last verse translation. A distinguished version, also faithful to the rhyme and meter, appeared in 1995, this one by James Falen, Professor of Russian at the University of Tennessee. Ljuba Tarvi in her PhD thesis Comparative Translation Assessment: Quantifying Quality attempts a quantitative measure of the goodness of the translations available to her, and concluded that overall Falen’s was the best. It was the verse translation chosen for inclusion in the edition of The Complete Works of Alexander Pushkin which appeared in 1999 and was the first complete edition in English, although that edition also included a prose translation by Roger Clarke. A good summary of the differences between the translations is given by Barry P. Scherr in the Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English. It is probably fair to say that, as Scherr puts it, in terms of quality there is little to choose between the versions of Arndt, Johnson and Falen, although all three read quite differently. 2