GRAPHIC EQUIVALENCE IN TRANSLATED TEXTS: A

advertisement

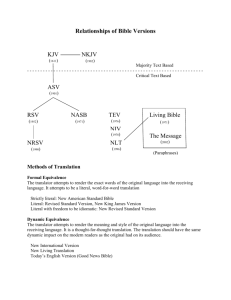

GRAPHIC EQUIVALENCE IN TRANSLATED TEXTS: A STATISTICAL APPROACH Ljuba Tarvi Abstract. This paper presents a model of measuring equivalence between a source text and its translation(s), which makes possible their comparison without resorting to subjective impressions and prescriptive practices. The model, tentatively termed Graphic Equivalence Method (GEM), is a systematic measuring of the ST – TT(s) equivalence based on the use of simple statistics. The approach could be seen as ‘positive statistics’ as it is based on looking not for what is lost but for what is retained in translation(s). The method will be used here to demonstrate the evolution of Vladimir Nabokov’s translation strategy by comparing his three translations of the same poetic text made at various periods of time. The method has been devised as a means of comparative analysis of the English translations of Alexander Pushkin’s novel in verse Eugene Onegin for my post-graduate research work. This paper is the first attempt to present the model, and, doubtless, the idea needs further elaboration. 1. Introduction When examining both critical reviews and theoretical surveys aimed at unifying various approaches to assessing and comparing translated texts (e.g. James S. Holmes [1988], André Lefevere [1975, 1992], George Steiner [1975, 1989], Robert Wechsler [1998], Douglas Hofstadter [1997]), one gets an impression that the only commonly employed systematic approach might be termed ‘studying the patterns of error-making’, and it consists of (1) creating a corpus of translators’ errors and ‘shifts’, (2) discovering categories of the latter, and (3) converting the obtained abstractions into a theory (Hofstadter 1996: 414). The approaches to the comparative analysis of several translations of one text seem to share the same drawbacks, well described as follows: Though there are many critical comparisons of original source language text and one target language translation, no formalized means exists for assessing the relative merits of two or more translations of the same poetic text, and of presenting that assessment to readers of the target language who are not familiar with the source language. Without such a means judgements — including many publishers’ judgements — remain acts of faith; debate is limited to the translators themselves and conducted often in largely subjective terms; the uninitiated must judge translated poems for their intrinsic artistic merit alone and not for their ‘closeness’ to the original. (Cook et al. 1989) In my view, the basic problems of comparing translations cluster around the following ‘centers of gravity’: (1) selecting material for analysis; (2) framing, or choosing a unit of comparison and a systemic frame of reference to compare translations; (3) profiling, or summarizing the obtained results; and (4) subjectivity and value judgements. Below I shall briefly consider each of the above problems and offer my ideas for overcoming the difficulties outlined. As counter-argument material, I will use quotations from a recent work in comparative translation studies of poetic texts, Efim Etkind’s “Wine or Vinegar (On the Translatability of Poetry)” (1997). (1) Selecting, one of the biggest challenges in comparative studies, means reducing the 1 amount of the material to be compared to a manageable size. The problem to solve is: Which portion of the linguistic data of the ST is to be selected for solving the problem(s) posed? On the one hand, the selected section should be small enough to allow its analysis; on the other hand, it should be representative of the text as a whole. Etkind, for instance, selected one stanza of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, the dedication to the novel, nowhere in the text indicating his reasons for the choice. I believe that any part of an integral translated work can be selected for analysis provided the reasons for the choice are made explicit, otherwise there is a temptation to select those excerpts which would ensure that pre-planned results are obtained. (2) Framing concerns selecting analytical tools and parameters of comparison. The problem to solve is: What is the correct structure for representation of the chosen ST portion so that its relevant comparison with its TT counterpart is ensured for solving the problem(s) posed? In his comparative study, Etkind starts with a detailed description of the ‘architecture’ of the seventeen-line stanza from the viewpoint of its semantic, semantic-syntactic, prosodic, and rhyme/sound segmentation (1997: 269-270). As a frame of reference, the description seems to be systematic and multi-faceted. An essential preliminary step is determining the basic entity with which to operate. Since in this case study I have to do with a poetic text, I have to monitor not only the semantic but also the poetic side of the matter. I choose, therefore, the two frames of comparison, hereafter referred to as content and form frames, each built on its own unit of comparison. Following Vinay & Darbelnet, who believe that translators have to be concerned more with semantics than structure, the unit of translation I postulate here for content framing is a lexicological unit, i.e. a word as a graphic unit, viewed here as a section of a written text flanked on both sides by empty spaces or punctuation signs, hereafter referred to as a ‘token’. The unit of translation I postulate here for poetic form framing is a poetic line. In an attempt to be systematic in framing, I have borrowed from Vinay & Darbelnet the idea of ‘segmentation’, or numbering the ST and TT units, which makes it possible to verify that every unit has been translated. Therefore, I start my way of measuring the ST – TT(s) equivalence by consecutively numbering every graphic unit, or token, in the original text, following the strict policy ‘one token, one number’. ‘Equivalence’ is a loaded term in translation studies, one of those ubiquitous notions “roughly understood as a translation’s capacity to be received as if it were the source text” (Pym 1998: 156) that have become well-worn through overuse. (For a concise overview of the concept of equivalence in translation studies see Chesterman 1998: 16-27.) Time and again, translation theorists, philologists and philosophers have tried to oppose terminology like similarity, analogy, adequacy, invariance and congruence, only to go on to redefine ‘equivalence’ for their own concepts. In my approach, my goal is to estimate the relative distance between a set of TTs and their original by finding the position of each TT on a certain ‘continuum of fidelity’ as regards the ST. One of the advantages of the method I propose is its modular design, which allows one to include any number of aspects (modules) of comparison, each calculated as a proportion per hundred. If several frames are used to monitor one linguistic plane, the general result is expressed as the arithmetic mean of the percentages of the corresponding modules. (3) Profiling is the comparison proper, which is carried out after the framework has 2 been outlined. The question to solve is: How much of the representation model of the chosen ST portions overlaps with those of its translated counterpart? Etkind, having presented his frame of reference, proceeds to compare some translations of the selected stanza into German (by Commichau, Brown, Bush, Keil), French (by Perot), and English (by Arndt, Johnston). His comments, however, are unevenly distributed among the compared translations and reduced to remarks like “the segmentations noted in the original are recreated” (274), “[the translation] limps a bit” (275), “the translation is clumsy and can be read only with difficulty” (275), etc. Therefore, the systematic approach for comparison outlined in the introductory part of his article remains unrealized in his paper. Within the Graphic Equivalence approach, the profile obtained when comparing any frame of reference with that of its translated counterpart(s) is expressed in terms of figures. The idea of employing figures for monitoring the ST – TT(s) equivalence was prompted by Nabokov’s remark: “Promoters and producers of what Anthony Burgess calls ‘arty translations,’ carefully rhymed, pleasantly modulated versions containing, say, eighteen per cent of sense plus thirty-two of nonsense and fifty of neutral padding …” (1966: 80). Presenting the obtained results in terms of figures, which express what share of the elements has been retained, makes it possible to compare translations in an objective way. (4) No critic of translated texts can be impartial. Some bitter remarks on certain drawbacks of particular translations sometimes turn into prolonged critical battles, such as, for instance, Matthew Arnold’s carping at Francis Newman’s rhymed translation of Homer in his Lectures on English Literature (1860), or Edmund Wilson’s attack on Nabokov’s literal Eugene Onegin in “The Strange Case of Pushkin and Nabokov” (1965). If we return to Etkind’s analysis, one of his typical conclusions goes: “Busch’s translation has many weaknesses, and is vastly inferior to Keil’s. Nevertheless, in spite of everything, it possesses more vitality, and even more similarity to the original, than Braun’s prosaic ‘treatise’” (276). I would again like to quote Thomas, who expressed what seems to be a rightful claim of the translator who spent years “weighing every word, every phrase, in terms of its sense and its place in the rhythmic structure of the poem” (1982: 23). This is how the translator concludes his ‘defense’ against the critic: “[Simon Karlinsky] has every right to dislike my translations and to say so; he has no right to question my integrity on the basis of that dislike. One part of his denigration is based on a value judgement; the other part is based on nothing at all …” (1982: 24). In contrast, the Graphic Equivalence method, systematic not only in its framing but also in its profiling stage, works without evaluative words. As will be shown below, its results can be presented as simple graphs or tables. 2. The Graphic Equivalence Method When elaborating my theoretical framework, I followed the commonsensical approach of the following kind: “The basic ideas are these: if one wanted to be somewhat simple-minded about linguistic communication, one would perhaps describe it as involving two things: (1) picking out some entity in the world; (2) saying something about that entity” (Allwood et al.: 132). As applied to translation studies, the problem can be reformulated as follows: if one wanted to be somewhat simple-minded about an ST-TT comparison, one would perhaps describe it as involving four things: (1) picking 3 out some entity in the ST; (2) finding its TT counterpart; (3) describing them both within the same framework; (4) comparing the resulting ST and TT descriptions. Having determined my goals, I start framing the chosen text (2.1.1) in terms of two basic units of comparison, a graphic unit, or a token (2.1.2) and a poetic line (2.1.3). The first step is a consecutive numbering of all the ST tokens. The next step is to look for their TT counterparts in terms of semantics, which, if found, get the numbers of their ST counterparts. There are few cases when, in a given context, a word has an exact counterpart in another language, i.e. when there is one signified for two signifiers, as, for instance, knife and couteau in the context of table knife (Vinay & Darbelnet 1995: 12-13). Within the basic frame of comparison based on semantic equivalence, there can be various relations between a single ST token and its TT counterpart. In this case study, there are, in terms of Vinay & Darbelnet, simple units (a single ST token corresponds to a single TT one, e.g. strasti > passions), and diluted units (a single ST token corresponds to more than one TT token, e.g. nozhki > little feet) (for a detailed classification of such correlations see Vinay & Darbelnet 1995: 22-27). When both ST and its TTs have been compared semantically and their counterparts, if retained in translation, have been labeled with the corresponding ST numbers, we can proceed to the comparison proper. The source text, in all the totality of its numbered tokens, is always 100%, while the results for every TT are calculated in terms of percentages of their overlapping with the ST. The approach does not imply that more retained elements means a better translation, but rather that the more elements coincide, the closer, or more equivalent, the translated text is to the original in terms of the chosen linguistic level. 2.1 Eugene Onegin by Alexander Pushkin and Vladimir Nabokov As Nabokov once famously noted, “Onegin has been mistranslated into many languages” (1955: 505). The first complete authorized edition of the novel in verse Eugene Onegin by Alexander Pushkin (1799 – 1837) was published in 1837, shortly before the author’s untimely death in a duel. The first complete English translation appeared in 1881, and since then the novel has been translated into English eighteen more times, with every translation but the one by Vladimir Nabokov (1964) preserving the poetic form of the original. In 1975, Nabokov published a revised version of his literal translation, having emphasized his determination to violate the poetic form of the original to an even greater extent in order to make the sense clearer. But Nabokov had not always been a staunch defender of the literal way of translating Eugene Onegin. In 1945, he had published his rhymed translation of three stanzas of Chapter One, XXXII-XXXIV. 2.1.1 Selecting For the present study, I selected the last six lines (9-14) of Stanza XXXIV as Nabokov translated them in 1945, 1964, and 1975. The choice is prompted by the considerations of space and by a richer rhyme pattern at the end of the Onegin stanza structure. The aim of the study is to demonstrate the working of the Graphic Equivalence method by monitoring, albeit on the limited material of the selected lines, the dynamics of Nabokov’s evolution as translator. 2.1.2 Content equivalence ‘Meaning’ is, of course, a problematic term. In the present analysis, I neither distinguish among different levels of a word meaning, nor consider whether a word has 4 been translated well, but first simply check if the word (token) has been translated at all. To this end, in my first frame (Column I), I start with a consecutive numbering of all the 25 tokens of the chosen lines of the original, which allows me to accomplish two tasks: (1) to make a complete inventory of my linguistic material and (2) to use the same numbers for denoting the TT counterparts, if the tokens in question have been retained in translation. As I have mentioned earlier, depending on the purposes, frames of any kind can be used in comparative analysis within the model. Since the goal of this paper is to demonstrate the abilities of the method, I will build another frame to depict the degree of the linguistic ‘make-up’ preserved in the retained tokens, i.e. such grammatical features as their word class and syntactic function (column II). There are, therefore, the following two aspects to be considered in the present analysis. Token equivalence (TE): column I in the frame below indicates if any given numbered token has been retained in translation at all. If it has, irrespective of the way it has been done either stylistically or grammatically, its number is presented in the column. Formal equivalence (FE): column II indicates which of the retained tokens preserve the same grammatical features as their original counterparts, irrespective of their stylistic peculiarities. For instance, both Nabokov’s translations of the word strasti, i.e. passions and emotions, are considered retained because grammatically they are plural forms of nouns, as in the original. Translation by a singular noun or conversion into a verb would mean non-appearance of the code for strasti in column II. If, therefore, the retained token is rendered by the same part of speech expressed in the same grammatical category, its number is presented in the column. Next I present the frames of the original and of Nabokov’s versions of 1975, 1964, and 1945, framed in the way described above. If in one of the TTs below, more than one English word is used to retain a single Russian token, the English counterpart is underlined: ‘Tis enough to render the Russian pólno which is a shortened form of the adjective pólnyi meaning full; haughty ones to translate the Russian substantivized adjective nadménnye; are (not) worth for the Russian expression (ne) stóyat; and little feet to render the Russian nózhki, since in Russian nogá is both a leg and a foot, while nózhka is a diminutive to refer to a finely shaped woman’s foot. One: XXXIV (9-14) (Alexander Pushkin) 9. (1)No (2)pólno (3)proslavlyát’ (4)nadménnykh 10. (5)Boltlívoj (6)líroyu (7)swoéj; 11. (8)Oni (9)ne (10)stóyat (11)ni (12)strastéj, 12. (13)Ni (14)pésen, (15)ími (16)vdokhnovénnykh: 13. (17)Slová (18)i (19)vzór (20)volshébnits (21)síkh 14. (22)Obmántchivy … (23)kak (24)nózhki (25)íkh. Nabokov (1975) I (TE) II (FE) 9. (1)But (2)‘tis enough (3)extolling (4)naughty ones 1, 2, 3, 4 1, 2, 3, 4 10. with (7)my (5)loquacious (6)lyre: 7, 5, 6 7, 5, 6 5 11. (8)they (9)are (10)not worth (11)either the (12)passions 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 12. (13)or (14)songs by (15)them (16)inspired; 13, 14, 15, 16 13, 14, 15, 16 13. the (17)words (18)and (19)gaze of (21)these (22)bewitchers 17, 18, 19, 21, 20 17, 18, 19, 21, 20 14. (22)are as deceptive (23)as (25)their (24)little feet. 22, 23, 25, 24 22, 23, 25, 24 25 (out of 25) 25 (out of 25) 100% 100% Nabokov (1964) I (TE) II (FE) 9. (1)But (2)‘tis enough (3)extolling (4)naughty ones 1, 2, 3, 4 1, 2, 3, 4 10. with (7)my (5)loquacious (6)lyre: 7, 5, 6 7, 5, 6 11. (8)they (9)are (10)not worth (11)either the (12)passions 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 12. (13)or (14)songs by (15)them (16)inspired; 13, 14, 15, 16 13, 14, 15, 16 13. the (17)words (18)and (19)gaze of (21)the said (22)charmers 17, 18, 19, 21, 20 17, 18, 19, 20 14. (22)are as deceptive (23)as (25)their (24)little feet. 22, 23, 25, 24 22, 23, 25, 24 25 (out of 25) 24 (out of 25) 100% 96% Nabokov (1945) I (TE) II (FE) 9. (1)But really, (7)my (5)loquacious (6)lyre 1, 7, 5, 6 1, 7, 5, 6 10. (3)has lauded (4)haughty belles too long 3, 4 11. – for (8)they (10)deserve (11)neither the (14)song, 8, 10, 11, 14 8, 10, 11 12. (13)nor the (12)emotions (15)they (16)inspire: 13, 12, 15, 16 13, 12 13. (19)eyes, (20)words – all their (22)enchantments cheat 19, 17, 22 17 6 100% 100% 14. as much (23)as do (25)their (24)pretty feet. 23, 25, 24 23, 25, 24 20 (out of 25) 14 (out of 25) 80% 56% 68% I will now explain the way I calculate the results using the example of the last frame above, that for Nabokov (1945). Column I, called Token Equivalence (TE) above, lists the tokens which are retained semantically, i.e., irrespective of their stylistic, syntactic, morphological, etc. features. By this parameter, Nabokov has lost five ST tokens: 2, 9, 18, 20, and 21. Token 20 is retained in both later versions, as charmers in Nabokov (1964) and as bewitchers in Nabokov (1975), but in the rhymed version, the translator changes the doers of the action, charmers, into an instrument, enchantments, which substitution results in the loss of token 21, which is the determiner of token 20, translated as their in 1945 and turned later into the said (1964) and these (1975). Token 9, which is a grammatical negation in the ST fully retained in both later versions, is lost in the rhymed version because here Nabokov uses the lexical negation neither … nor, which in English precludes, unlike the case in the Russian language, the use of the second negation, not. Token 18 is the connector and, omitted to preserve the syllable count in the line. Finally, token 2, rendered in later versions as ’tis enough is translated here as really which does not, at least in my view, convey the semantic value of the token. Thus, Nabokov retained 20 tokens out of 25, which results in 80% of semantic faithfulness. Let us now have a closer look at column II, called Formal Equivalence (FE) above, which lists those of the retained tokens which preserve the grammatical features of the original, e.g., part of speech, gender, number, etc. In this frame, Nabokov loses six more tokens: 3, 14, 15, 16, 19, and 22. Tokens 14 and 19, song and eyes (1945), are in the two later versions rendered in the same number as in the original, as songs and gaze, respectively; tokens 15 and 16, they inspire (1945) are rendered in both later versions in the passive voice, as in the original, by them inspired; token 3, has lauded, has later been replaced with extolling, like the ST impersonal form; token 22, cheat, is later rendered, as in the original, as are deceptive. Therefore, in the formal frame, Nabokov retained 14 tokens out of 25, which comprises 56% of the original. 2.1.3 Form equivalence Since the analyzed text is poetic, it has to be examined as regards its poetic form as well. In this kind of analysis, the focus of attention is such structural elements of the whole text as its segmentation into lines and the endings of the lines, the rhymes. I first examine how closely the translator has been able to retain the components of the Onegin stanza, which is an intricate sonnet form characterized by strict laws of construction. The selected lines are described in terms of the most common prosodic parameters: rhyme pattern (RP) and syllable count (SC), which are characterized below. Column I (rhyming pattern, RP). Each Onegin stanza has a fixed pattern of feminine (female or double) rhymes designated here by capital letters, which terminate in one unstressed syllable (lyre / inspire), and masculine (male) rhymes, designated here by 7 small letters, which terminate in a stressed syllable (long / song). The part of the Onegin stanza considered here has the following rhyme scheme: AbbA cc, displaying a sandwiched pattern for a quatrain (AbbA), crowned by a closing couplet (cc). Column II (syllable count, SC). Each full stanza consists of alternating eight- or nine-syllable lines. In the six lines of the ST excerpt, the selected lines exhibit the following regularity: 9889 88. The table below presents the frames of the chosen six lines in the original and as translated by Nabokov in 1975, 1964, and 1945, starting from his latest and most exact version. One: XXXIV (9-14) (Alexander Pushkin) I (RP) II (SC) 9. No pólno proslavlyát’ nadménnykh A 9 10. Boltlívoj líroyu swoéj; b 8 11. Oní ne stóyat ni strastéj, b 8 12. Ni pésen, ími vdokhnovénnykh: A 9 13. Slová i vzór volshébnits síkh c 8 14. Obmántchivy … kak nózhki íkh. c 8 6 (100%) 6 (100%) Nabokov (1975) I (RP) II (SC) 9. But ‘tis enough extolling naughty ones a 10 10. with my loquacious lyre: B 7 11. they are not worth either the passions C 9 12. or songs by them inspired; B 7 13. the words and gaze of these bewitchers D 9 14. are as deceptive as their little feet. e 10 0 (0%) 0 (0%) Nabokov (1964) I (RP) II (SC) 9. But ‘tis enough extolling naughty ones a 10 10. with my loquacious lyre: B 7 11. they are not worth either the passions C 9 12. or songs by them inspired; B 7 13. the words and gaze of the said charmers D 9 14. are as deceptive as their little feet. e 9 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 8 Nabokov (1945) I (RP) II (SC) 9. But really, my loquacious lyre A 9 10. has lauded haughty belles too long b 8 11. – for they deserve neither the song, b 8 12. nor the emotions they inspire: A 9 13. eyes, words – all their enchantments cheat c 8 14. as much as do their pretty feet. c 8 6(100%) 6(100%) When comparing the frame of every translation with that of the original, one can, for instance, see that the zero result in columns I (rhyme type) and II (syllable count) in Nabokov (1964, 1975) means that neither rhyme type nor syllable count have been retained there in a single line, while in his earliest version of 1945 Nabokov preserved both parameters in every line, which amounts to 100% of faithfulness. 3. Discussion The table below presents the obtained results, expressed in percentages and arithmetic means (totals), scored in the three Nabokov versions in all the categories considered. FORM (%) TOTAL I (RP) II (SC) Nabokov (1945) 100 100 Nabokov (1964) 0 Nabokov (1975) 0 TOT AL CONTENT (%) I(TE) II(FE) 100 80 44 68 0 0 100 96 98 0 0 100 100 100 To profile Nabokov’s changing translation strategy graphically, the obtained results can be presented as the scheme below. The translator moves from 100% of form (based on line comparison) and 68% of content (based on token comparison) retention in 1945 to a dramatically different result in both literal versions, where 0% of the poetic form is retained, but the content retention increases from 98% (1964) to 100% (1975). FORM (LINE) CONTENT (TOKEN) 9 Pushkin (1837) 100% 100% Nabokov (1945) 100% 68% Nabokov (1964) 0% 98% Nabokov (1975) 0% 100% In his striving to bring Pushkin closer to the Anglophone reader, Nabokov not only changed the basic mode of translation from literary (1945) to literal (1964), but he also found ways of perfecting his literal mode, which resulted in a somewhat closer fit in terms of content (1975). During the heated polemics around his version of 1964, Nabokov once remarked, “I have often been asked to allow the reprinting of my old verse translations (such as the three stanzas in the Russian Review, 1945 [...]) and have always refused since they are [...] lame paraphrases of Pushkin’s text” (Nabokov 1964: 16). Judging by the figures (68%), Nabokov’s paraphrases are not so ‘lame’. Nonetheless, “a choice between rhyme and reason”, as Nabokov called his vacillations between the modes of translation (1955: 505), was made in favor of ‘reason’. Guided by the following two principles: (1) “I take literalism to mean ‘absolute accuracy’” (1955: 510), and (2) “It is possible to translate Onegin with reasonable accuracy by substituting for the fourteen rhymed tetrameter lines of each stanza fourteen unrhymed lines of varying length, from iambic dimeter to iambic pentameter” (1955: 512), Nabokov raised his semantic score from 68% (1945) to 98% (1964). But the translator remained unsatisfied with his work: “My EO falls short of the ideal crib. It is still not close enough and not ugly enough. In future editions I plan to deflower it still more drastically” (1966: 80). And so he did. In his revised version of 1975, he set himself a double task: to achieve a closer line-by-line fit, and to refine the vocabulary to clarify the difference between the same Russian words used in various meanings (1975 (I): xiii). Even the present study, meant to demonstrate the Graphic Equivalence method on the limited material of the selected lines, has revealed an increase in the quantitative correspondence to the original from 98% to 100%. 4. Conclusion To present the obtained results, I do not have to resort to any kind of evaluative remarks, as the figures and tables are self-explanatory. One might argue that had the selected parameters been different, the result could have been different too. True, but in this case the compared texts would again have been considered under equal conditions so as to reveal their correlation with a different frame of reference of the same original text. By choosing a printed word as a basic unit of comparison I facilitate easier handling of the linguistic material, as this choice ensures both complete inventorying through simple coding and presentation of the obtained results in percentages. The Graphic Equivalence method, where ‘graphic’ denotes the way of presenting the results, and ‘equi-’ denotes a measure of ST-TT distance, might prove a useful, though not all-embracing, tool for analyzing translated texts. The simplicity of the method, its modular flexibility and high sensitivity make it suitable for solving both theoretical and practical problems. I would like to conclude with Nabokov’s words, “My method may be wrong but it is a method, and a genuine critic’s job should have been to examine the method itself instead of crossly fishing out [...] some of the oddities [...]” (1966: 84). 10 E-mail: ljuba.tarvi@pp.inet.fi REFERENCES Allwood, Jens, Andersson Lars-Gunnar & Dahl, Östen (1979) Logic in Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chesterman, Andrew (1998) Contrastive Functional Analysis. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. Cook, Guy & Poptsova-Cook, Elena (1989) “Two Translations of a Poetic Text: The First Stanza of Pushkins’ “Zimnee utro” (“Winter Morning”).” Journal of Russian Studies 55. 8-21. Etkind, Efim (1997) “Wine or Vinegar (On the Translatability of Poetry).” Essays in the Art and Theory of Translation. Eds. Grenoble, Lenore A. & Kopper John M. Lewingston, Queenston: Lampeter. 265-282. Holmes, James Stratton (1988) Translated! Amsterdam: Rodopi. Karlinsky, Simon (1982) “Pushkin Re-Englished.” The New York Times Book Review, September 26, 11. 25-26. Lefevere, André (1975) Translating Poetry. Seven Strategies and a Blueprint. The Netherlands: Van Gorcum. Lefevere, André (1992a) Translating Literature. Practice and Theory in a Comparative Literature Context. New York: The Modern Language Association of America. Lefevere, André (1992b) Translation, Rewriting, and the Manipulation of Literary Fame. London and New York: Routledge. Nabokov, Vladimir (1945) “From Pushkin’s “Eugene Onegin”. Translated from the Russian by Vladimir Nabokov (Chapter 1, XXXII-XXXIV).” Russian Review IV, 2 (Spring 1945). 38-39. Nabokov, Vladimir (1955) “Problems of Translation: “Onegin” in English.” Partisan Review, XXII, 4 (Fall 1955). 496-512. Nabokov, Vladimir (1964) “On Translating Pushkin. Pounding the Clavichord”. The New York Review of Books, II, 6 (April 30, 1964). 14-16. Nabokov, Vladimir (1966) “Nabokov’s Reply”. Encounter, XXVI, 2 (February 1966). 80-89. Pym, Anthony (1998) Method in Translation History. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing. Steiner, George (1989) “The Hermeneutic Motion”. Readings in Translation Theory. Ed. Chesterman, Andrew. Helsinki: Finn Lectura. 25-32. Thomas, D.M. (1982a) The Bronze Horseman: Selected Poems of Alexander Pushkin. New York: Viking. Thomas, D.M. (1982b) “D.M. Thomas on his Pushkin.” The New York Times Book Review, October 24. 15. Vinay, Jean-Paul & Darbelnet, Jean (1995 [1958]) Comparative Stylistics of French and English. A Methodology for Translation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. Wechsler, Robert (1998) Performing Without a Stage. The Art of Literary Translation. North Haven: Catbird Press. Wilson, Edmund (1965) “The Strange Case of Pushkin and Nabokov.” The New York Times Book Review, July 15. 3-6. 11 From: The Electronic Journal of the Department of English at the University of Helsinki (ISSN 1457-9960), Volume 1 (2001) Translation Studies © 2001 Ljuba Tarvi http://blogs.helsinki.fi/hes-eng/volumes/volume-1-special-issue-on-translation-studies/graphic-equivale nce-in-translated-texts-a-statistical-approach-ljuba-tarvi/ 12