Yeh-uh Hsueh Chen and Mei

advertisement

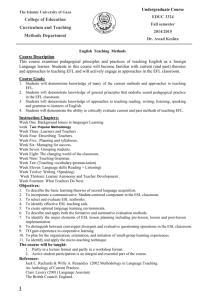

Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia STRENGTHENING TEACHER-LEARNER BOND THROUGH DIFFERENTIATED ASSESSMENT Yeh-uh Hsueh Chen1 and Mei-Ling Lee2 Chienkuo Technology University, Taiwan (1yuhc@ctu.edu.tw, 2tulip0084@gmail.com) ABSTRACT Traditional one-size-fits-all tests pinpoint grading as the primary purpose. Such evaluation inevitably causes stress that may be destructive enough to adversely widen the distance between the teacher and students (Palmer, 1998). Detrimental tension in the assessment setting often presents barriers to the development of intellectual abilities (Shepard, 2000). To encourage learning through positive interactions in the classroom, teaching practitioners are in need of assessment options that not only document students’ progress, provide information for instructional decisions, but also bridge the gap between teachers and students. This qualitative study examined teacher-learner relationship in an authentic assessment context where learner-centered tiered performance tasks were offered in an effort to bond teachers and learners. A total of 12 participants were interviewed, either individually or in focus groups to explore their perspectives on the assessment. Findings indicated assessment that addresses diverse learner needs is favored over traditional tests. Self-directed choices of tiered tasks improve test takers’ motivation, confidence, and achievement. Data also suggested that teacherlearner bond is strengthened in the learner-centered assessment while culturally-related learning styles and beliefs about teacher and learner roles were in play. KEYWORDS Teacher-learner relationship, Differentiated instruction, Tiered performance tasks, Assessment, Tertiary EFL classrooms, Qualitative study INTRODUCTION Traditional summative test has long been accused of widening the distance between teachers and students (Palmer, 1998). Conventional grading systems adopt one-size-fits-all format to generate summative judgment of student achievement that does not inform instruction (Liao, 2007; Tompkins, 2002). In a worse scenario, a conventional test context could cause stress detrimental to learner autonomy and it eventually closes the door on long-lasting and meaningful learning. In Taiwan, the practice of Teaching English as a Foreign Language (EFL) suffers from powerful influences of traditional uniform tests. According to Liao (2007), the pressure for academic success is so intensive that more than 80 percent of EFL teachers train students for high scores in summative tests rather than communicative competence in real life. Students are de-motivated because their hard work does not warrant a transfer of knowledge to realworld situations and the lack of proper English proficiency in students has worried the English educators in Taiwan. 1 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia Research has shown that language learning takes place best in an environment where constructive interpersonal relationship and interaction are encouraged (Ma, 2005). Ito and Chen (2007) suggested that in differentiated instruction (DI) approach language teachers are able to take care of both students’ academic and affective needs and make optimal student growth possible. As a humanistic approach, DI honors learning ownership by using tiered performance tasks (TPT) to assess students at different levels. Learners are encouraged to choose preferred task to demonstrate knowledge and ability without much stress. As Taiwanese students are generally conditioned to uniform tests, how will they respond to TPT that offers leveled choices in assessment? Will the students view the teacher differently for administering the unusual assessment? How will the learner-centered assessment influence teacher-learner relationship? This case study was conducted to examine student responses to a final examination employing TPT, and thereby the participants’ views of assessment as well as the teacher. Discussions about cultural influences on teacher and learner roles arose from the findings and the implications for EFL classrooms in Asian regions are suggested. LITERATURE REVIEW Assessment There are two broad categories of assessment: summative and formative assessment. The former, the traditional product approach, provides a summary judgment about learning achieved after some time with the goal of informing external audiences primarily for certification and accountability purposes. The latter, the new process approach, gathers and uses information about students’ knowledge and performance and informs teachers to adapt instruction to address identified deficiencies. Frohbieter et al. (2011) suggest that the primary purpose of a formative assessment is ongoing instructional improvement. In other words, formative assessment functions as an integral part of instruction to support and enhance learning (Shavelson, 2006; Shepard, 2000). Tompkins (2002) indicates that in authentic assessment teachers examine both the learning processes and the artifacts or products that students produce. Meanwhile, students participate in reflecting on and self-assessing their learning. Authentic assessment operates not only as a way “to monitor and promote individual students’ learning”, but can be used “to examine and improve teaching practices” (Shepard, 2000, p. 12). If carefully planned and well implemented, “good assessment tasks are inter-changeable with good instructional tasks” (Roos & Hamilton, 2004, p. 8). In this sense, formative assessment serves the purpose. Unfortunately, current assessment systems present barriers to the development of intellectual abilities and students’ self-esteem (Black & Wiliam, 2001). The prevailing uniform testing fails to attain true understanding of how well students can perform. In addition, teaching to summative tests demoralizes learners where students take little responsibility for their own learning (Shepard, 2000). To nurture motivated life-long learners, teachers need to abandon conventional way of assessment and develop evaluation means that encourage autonomous learning for the pursuit of applicable skills in authentic situations. 2 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia Differentiated Instruction and Differentiated Assessment Tomlinson and Eidson (2003) refer the term DI as “a systematic approach to planning curriculum and instruction” (p.3) for heterogeneous student populations. In DI teacher strategically adjusts the content, process and product of instruction, in accordance with individual needs (Gregory & Chapman, 2002). The differentiating adjustment may be made in various aspects, such as complexity level (e.g., knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, evaluation), students’ preferred learning modalities (e.g., auditory, visual or kinesthetic), and learner interests. Differentiating EFL educators interacts with students as a facilitator, role model, resource, and nurturer, while students find meaning in what they do through purposeful activity and reflection, and are provided access to the skills and knowledge with which to fulfill their goals (Chen, 2007). “While learning tasks need to be differentiated, so do assessment strategies”, asserted Gregory and Chapman (2002, p. 55). One of the formative differentiating assessment practices often employed in DI is the strategy of tiered performance tasks (TPT). TPT are evaluation task options designed to accommodate diverse educational needs of individual learner and stretch students’ understanding and skills. In EFL, TPT are employed to encourage demonstration of different dimensions in learning: facts, concepts, principles, attitudes, and skills. Nunley (2006) claims that systematic use of differentiated assessment strategies supports high motivation and leads to learner autonomy, as relieving stress from tests among students. Differentiated instruction promotes language learning ownership through an encouraging teacher-learner relationship (Ito & Chen, 2007). When the teaching atmosphere is harmonious, alleviating foreign language anxiety, the students feel comfortable and secure. Only then can the students have the confidence to explore in language learning and autonomy develops. A teacher-learner relationship that sustains the collaboration of a responsive teacher and engaging students is crucial to optimal foreign language learning. Needed Reforms to EFL in Taiwan In Taiwan, teacher-centered instruction dominates the EFL field considerably due to the potent influences of uniform paper-and-pen examination (Nunan, 2003). Drilled by tests and quizzes, students often give up learning or pass standardized tests without the needed communicative competence (Chen, 2007). Reform advocates believe that to improve the quality of English education in Taiwan, more learner-responsive instruction and formative assessment should be brought into daily practice (Dai, 2003; Liao, 2007). Specifically, by taking differentiating approach, an EFL teacher relates to the students constructively, is motivated to make necessary changes in classroom practice, thus can be the key to student language learning. 3 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia METHODOLOGY This case study examined the educational implications that a learner-centered assessment may bring in terms of teacher-learner relationship. The study is exploratory in nature, investigating teacher-learner relationship as reflected in the participants’ responses to TPT, a differentiating assessment practice. In the final examination under study, the students had to perform at least two projects; the third one was only needed if the students wanted to work for bonus points. The tasks were differentiated in three complexity levels, basic, intermediate, and advanced, each worth different point values and designed to facilitate demonstration of knowledge, comprehension, and application of materials taught in the semester,. The students were free to make their choices of tasks and target a desired score range. Through purposeful sampling, 12 freshmen studying in the Department of Applied Foreign Languages (AFL) at a technology university in central Taiwan participated in the study. The informants came from a class with 48 students and were recruited based on their academic standings in and gender distribution of the class. There were four males and eight females, all were 18-19 years of age. The informants were invited to either one of the three individual interviews or one of the two focus groups, arranged to seek diverse representation of student levels, interests, and gender. An interview protocol and a moderator’s guide were prepared to ensure the same basic topics were explored in each interview. Other data gathering techniques included field observations, videotaping, and artifact collection. Triangulation and member check on verbatim transcriptions of the interviews were conducted for validity. The process of sorting data into meaningful interpretation involves coding, categorizing and theme-searching. FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS In the following discussion, some selected participant comments were tabulated and still some incorporated into text to provide a smooth flow of the findings through the insiders’ voices. Responses to TPT: Confusion to Recognition to Appreciation For all participants, this assessment was undoubtedly innovative. Its unconventional format drew from the participants a chain of reactions from confusion to recognition, and finally to appreciation. Indeed, the format was quite complex to understand for most students at the initial contact. To tackle the bewilderment, the instructor, Ms. Lin, provided extra time twice before the examination to clarify questions about requirements, point distribution scheme, and scoring criteria. Her idea was that students would want to achieve more when they have a clear understanding of what they need to do (Shepard, 2000). Recognition of assessment features rose after the initial shock had quelled. The most noticeable change in this examination lay in the offering of TPT for students to choose from. The participants realized those task choices actually attended to their individual readiness levels and fed in the sense of ownership. Several participants admitted feeling in control when making their own choices. Cheryl reflected, “On second thought, I think Ms. Lin was actually giving us the chance to make choices. She respects us. I feel great about it, about being respected.” 4 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia Being able to aim at a preferred score was the most appreciated merit of the assessment. After all, score is always a great concern for students and the participants in this study were no exception. Transparent success criteria triggered hidden ambitions when the participants decided what tasks to perform to target their preferred score range. On the whole, choosing projects to manipulate scores provided the participants a satisfying ownership in the evaluation of their learning. Lily spoke with a bright smile, “I think it is really nice because [Ms. Lin] gave us the choices. This is the part I am really pleased with....It’s democratic that we can make our own decisions!” In order to attain the target score, the participants had to stretch their ability. This enhanced confidence and improved English skills. Best of all, the participants enjoyed more ownership in the evaluation process. From a passive knowledge receiver the participants grew to an enthusiastic learner who took charge of one’s own learning objectives. However, there was also negativity towards the assessment. In general, the participants complained about demanding tasks, even though they eventually experienced improved English competence. As there were many other tests to deal with during the final examination week, the participants worried about insufficient time to prepare. Other down sides of the assessment included scheduling difficulties, and long assessment process. Table 1. Participant responses to TPT. Category Key Participant Comments confusion format changes Dick: “?” May: “We have never seen something like that [the all-in-English task descriptions and requirements]. We couldn’t understand it in the beginning.” recognition leveled tasks Ken: “it takes everybody’s ability level into consideration, so learning is propped up” appreciation clear criteria Lily: “Ms. Lin had told us scoring criteria.... Each task is allowed a certain number of points. She has shown us the rubric.” Jenny: “We are not restricted with only one kind of question. We can make our own choices.” Sandra: “I can target an acceptable score for myself.” Cheryl: “On second thought, I think Ms. Lin was actually giving us the chance to make choices. She respects us. I feel great about it, about being respected.” choices of tasks target scores feeling respected gains enhanced confidence to engage in challenges better English skills more learning ownership complaints Alex: “Mike and I decided to step out of fixed patterns and engage in new tasks for a try.” Jenny “it’s different this time, it’s somewhat more challenging and therefore brings about improvement…I had to work harder and spent more time, but the time was well spent.” Robin: “I assumed greater responsibility for the presentations than before.” Lily: “I think it is really nice because [Ms. Lin] gave us the choices. This is the part I am really pleased with....It’s democratic that we can make our own decisions!” scheduling difficulties Cheryl: “It’s so hard, so complicated!” Sandra: “I did three basic-level tasks because we had only limited time to prepare for the finals.… It’s easier to do basic-level ones, so I could save time for the other tests.” Jo: “It was tough to organize presentations for 48 people.” long process Robin: “It takes too much time to complete the whole thing.” demanding requirements insufficient preparation time 5 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia Learners’ Views of the Teacher While the participants appreciated the new assessment practice, no one recalled what rationale Ms. Lin provided behind it. They could only guess why she invested additional time to administer such a different assessment and increased her own workload. Some examples of the suppositions are listed in Table 2. Table 2. Learners’ views of the teacher. Category Key Participant Comments Conjectured teacher intentions To encourage learning Jo: I think she wanted us to try a different way to see if we would work harder. To inform teaching Robin: She wants to know our abilities better….In the past, she just threw out something for us to respond to, but this time we have to make our own decisions. Ken: This is a great idea…it helps the teacher to make decisions concerning the whole class. To address individual needs Lily: I think Ms. Lin did it considering that each student is at a different level; the level range in our class is pretty big. Sandra: Probably she doesn’t want to limit us within the range she sets, so we can decide the way we want. Students’ feelings and opinions are considered. to offer learning ownership Dick: She wishes that we will do it the way we like….to do what we want, to perform in our own way. Maybe it will bring out a better result. As shown in the table, Jo guessed from a good student’s view point. She associated examination with working hard, and thought Ms. Lin expected them to work harder. Robin and Ken thought about the assessment format; they guessed the format change had something to do with what Ms. Lin wanted to get from the examination for her future instruction. The leveled performance tasks were not easy to forget, and Lily and Sandra felt it was Ms. Lin’s good intention to attend to student needs. As for Dick, learning ownership was offered to help them perform better. All in all, the participants believed the new design of assessment was guided by the instructor’s intention to motivate learning, to get a better understanding of students’ levels for instructional improvement, to help student achieve their best potential, and to foster learner autonomy. Teacher-Learner Relationship in the Assessment Given the participants’ positive comments related to Ms. Lin, it is clear that they had established a healthy relationship with each other. The participants articulated their trust in the instructor’s willingness to address students’ needs. Seeing that the assessment had a complicated format and additional requirements for them, the participants understood that the changes meant heavier workload for the instructor, too. This was evidenced in Lily’s words: “…pronunciation weighed 20%, and content weighed 40%. For content, we had to email her the scripts and she would grade them based on the dialogue and grammar before the presentation. Then, she gave us scores based on the pronunciation and performance during the presentation.” Obviously, the instructor took the challenge along with her students and put herself in a more equitable position to the students, as Lily said: “It is democratic.” For this the participants believed that the instructor was with them and therefore accepted and appreciated the new form of assessment. It seems that acceptance and appreciation of the assessment arose from the participants’ trust in the instructor and in turn reinforced the teacher-learner bond. 6 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia Although welcome by most, learning ownership initiated inner struggle in certain participant. Preferring more guidance from the instructor, Cheryl indicated the need of external assistance. She stated, “If the teacher offers many choices, the test does not force us to work hard…. So, we all need some pressure to grow; pressure inspires our potential because adversity produces growth.” Then, she voiced the typical mindset of Asian students, “as students we cannot go up against [the teacher’s] decision, so we will have to change ourselves to meet the teacher’s objectives.” In addition, it seemed that Cheryl held doubts about students’ ability in executing learning ownership, as she added that it would be great if choices came with challenges slightly above the students’ current levels and aimed at learning goals preset by the instructor. Overall, in this first encounter with TPT, the participants acknowledged the differentiated assessment practice. They generally considered the experience constructive. Findings indicated positive results such as motivation in taking challenges, improved English skills, heightened self confidences, and better sense of ownership. The participants recognized TPT as an authentic form of evaluation and would welcome such assessment in the future. The exciting experience with TPT and a positive teacher-learner relationship mutually contributed to each other. IMPLICATONS AND SUGGESTIONS As evidenced in the interviews, the successful implementation of TPT relied on a healthy teacher-learner bond. When exploring deeper into this teacher-learner relationship, some deep-rooted cultural influences on teacher/learner roles surfaced. Research pointed out involving learners in the learning process is inevitably constrained by cultural related learning styles and beliefs (Lee, 2005; Littlejohn, 1983). Lee found that culturally derived beliefs and a perceived inability to learn independently of some Asian learners could impede students from adopting an autonomous learning approach. Asian students tend to regard teachers as expert figures and remain dependent. Littlejohn suggested probably the greatest limitation in applying notions of learner control is the learners themselves. Many English Learners in Taiwan may need to be supported and shown how to become self-aware and to reshape concept about assessment. Consequently, the teacher plays a crucial role in bringing learners into a more central role in making educational decisions. With the support of a solid teacher-learner relationship and a gradual approach toward relinquishing the teacher’s dominant role, a meaningful and fulfilling learning voyage of learners’ choice is likely to be realized. 7 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia REFERENCES Black, P.J. & Wiliam, D. (2001). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. London, UK: King’s College London School of Education. [British Educational Research Association short final draft]. Retrieved September 10, 2007, from: http://ditc.missouri.edu/docs/blackBox.pdf. Chen, Y.-U. H. (2007). Exploring the Assessment Aspect of Differentiated Instruction: College EFL Learners’ Perspectives on Tiered Performance Tasks (Doctoral dissertation, University of New Orleans, 2007). Dissertation Abstracts International, (UMI publication number 3226932) Dai, W.-Y. [戴維揚] (2003). 多元智慧與英語文教學 [Multiple intelligences and English language teaching]. Taipei, Taiwan: Shi-Da Publishing Co. Frohbieter, G., Greenwald, E., Stecher, B. & Schwartz, H. (2011). Knowing and doing: What teachers learn from formative assessment and how they use the information. (CRESST Report 802). Los Angeles, CA: University of California, National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST). Gregory, G. H., & Chapman, C. (2002). Differentiated instruction strategies: One size doesn’t fit all. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. Ito, N., & Chen, Y.-U. H. (2007). Differentiated Instruction to Alleviate Foreign Language Anxiety. Paper presented at The 41st Annual TESOL Convention/Graduate Student Forum, Seattle, Washington, USA. March 19-24, 2007. Lee, M.-S. (2005). The mismatch between students’ and teacher’s beliefs about learner autonomy. The Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Symposium on English Teaching, 2, 146-156. Liao, H.-C. (2007). Effects of cooperative learning on motivation, learning strategy utilization, and grammar achievement of English language learners in Taiwan (Doctoral dissertation, University of New Orleans, 2005). Dissertation Abstracts International, 67(07), 2498A. (ISBN 9780542781056) (UMI publication number 3226932) Littlejohn, A. P. (1983). Increasing learner involvement in course management. TESOL Quarterly, 17(4), 595-608. Ma, Y.-H. (2005). Students’ perceptions of learning activities in EFL college conversation class. The Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on English Teaching, 1, 497505. Nunley, K. F. (2006). Differentiating the high school classroom: Solution strategies for 18 common obstacles. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. Nunan, D. (2003). The impact of English as a global language on educational policies and practices in the Asia-Pacific region. TESOL Quarterly, 37(4), 589-613. 8 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Teaching and Learning (ICTL 2011) INTI International University, Malaysia Palmer, P. J. (1998). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life. San Francisco: CA: Jossey-Bass. Roos, B., & Hamilton, D. (2004). Toward constructivist assessment. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Nordisk Forening for Pedagogisk Forskning (NFPF), Reykjavik, 10-14 March, 2004. Shavelson, R. J. (2006). On the integration of formative assessment in teaching and learning: Implications for new pathways in teacher education. In F. K. Oser, F. Achtenhagen, & U. Renold (Eds.), Competence Oriented Teacher Training: Old research demands and new pathways (pp. 63-78). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers. Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29(7), 4-14. Tomlinson, C.A., & Eidson, C. C. (2003). Differentiation in practice: A resource guide for differentiating curriculum. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Tompkins, G. E. (2002). Language arts: Content and teaching strategies (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill. 9