File

advertisement

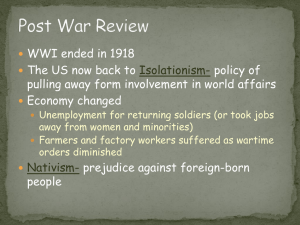

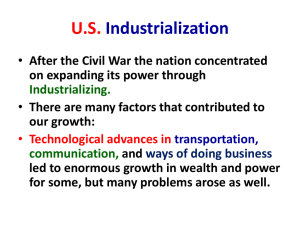

Early Immigration During the 1790’s, English radicals and Irish opposed to English rule fled their homelands to America. The Revolution in France brought new French arrivals at the end of the eighteenth century. Other French-speaking immigrants fled slave uprisings in Haiti and other West Indies colonies around the same time. These French-speaking newcomers settled mainly in coastal cities, notably in Charleston, New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia, as well as in New Orleans, which became part of the United States in 1803 as a result of the Louisiana Purchase. The most numerous non-English-speaking immigrants in the United States at the time of independence were Germans. Germans also constituted one of the significant immigrant groups at the opening of the nineteenth century. Many of those Germans came from what is now the southwestern part of Germany, which was then a poor area. Bad German harvests in 1816-1817 set in motion a flood of emigration out of that region. Although many of the emigrants moved east, to Russia, about 20,000 people from southwestern Germany came to America to escape famine. Immigration After the Steerage Act The year 1820 is the first year for which detailed immigration statistics for the United States are available, thanks to the Steerage Act of the previous year. During 1820, 8,385 immigrants arrived in the United States. Most, 43 %, came from Ireland. The second-largest group, 29 %, came from Great Britain. Hence, almost three-quarters of all immigrants who arrived in the United States during that year came from the British Isles alone. The next-largest groups came from the German states, France, and Canada. During the 1820’s, French immigrants moved ahead of Germans as the second-largest group after people from the British Isles. The second half of that decade also saw a steep rise in overall immigration, with the numbers of arrivals rising from slightly fewer than 8,000 in 1824 to more than 22,500 in 1829. People from Ireland, who already constituted the greatest single immigrant group during the 1820’s, were drawn to the United States by both continuing poverty in their original homeland and the growing demand for labor in America. For example, New York State’s Erie Canal, which was under construction from 1818 to 1825, drew heavily on immigrant Irish labor. That project began a long history of Irish immigrant labor helping to build the American transportation infrastructure. The rapid commercial success of the Erie Canal stimulated the building of more canals in other parts of the country, increasing the need for immigrant labor. At the approach of the mid-nineteenth century, some immigrants were drawn by the availability of land in the vast reaches of North America. Economic development also offered opportunities beyond agriculture for newcomers. Industrialization created jobs in mills and as manual laborers in cities. The expansion of railroads was another major force attracting immigrant labor. In 1830, the United States had a total of only 23 miles of railroad tracks. Only one decade later, this figure had grown to 2,818 miles. It rose to 9,021 miles in 1850 and 30,626 miles in 1860. Immigrants from Ireland played a particularly significant role in laying new railroad tracks. Economic hardships and political disorders in the sending countries also helped stimulate emigration to the United States. The most significant event was the Great Irish Famine of 1845-1851, which was caused by a devastating potato blight. Irish were already the most numerous immigrants, and the famine drove even more of them to leave their homeland in the hope of finding relief in North America. In the various German states—which would not be united under a single government until 1871—a wave of failed revolutions in 1848 created a flood of political refugees who swelled the ranks of German Americans. California’s large immigrant population in 1850 consisted mainly of people from Mexico. In the 1850 U.S. Census, Mexicans made up about 36 percent of the state’s foreign born. This was a heritage of California’s historic connection with Mexico. Other California immigrants came mainly from Ireland (15 percent of foreign born) and Germany (10 percent). California also had smaller percentages of immigrants from all over the world. Many immigrants were drawn to the state by the discovery of gold in 1849, but most people who flocked there at the beginning of the gold rush came from other parts of the United States. However, the state’s gold rush was about to stimulate a great wave of international immigration that would increase California’s foreign-born residents to 39 percent of the total population in 1860. Louisiana held the largest concentration of immigrants in the South in 1850. New Orleans, as the largest port in the South and the second largest in the nation after New York, was a natural place of entry for people from other countries. As elsewhere, the Irish made up the largest immigrant group in Louisiana. An estimated 26,580 Louisianans, or nearly 38 percent of immigrants, were Irish-born in 1850. The Irish who arrived after 1830 were most often poor peasants who settled in the area known as the City of Lafayette, which was later incorporated into New Orleans and is still identified as the Irish Channel, and provided much of the labor for digging the city’s system of canals. Late Ninteenth Century The U.S. Civil War put a temporary brake on immigration, but after it ended in 1865, the flood of immigration resumed. Rapidly developing industrialization saw the expansion of railroads, the building of large steel plants, and the exploitation of coal mines on unprecedented scales. All these and other developments drew great numbers of Europeans to the United States. Among the new immigrants were many Norwegians who, like the Germans, sought to exploit the agricultural lands of the Midwest and gave Minnesota and the rest of the Upper Midwest its heavily Scandinavian character. Other immigrants were beginning to come from eastern Europe, where the creation of large agricultural estates was diminishing opportunities for peasants to acquire land for themselves. This wave of immigrants peaked in 1907, a year during which more than six million new immigrants entered the United States. The Civil War was enormously destructive, but it also helped to stimulate the national economy and to push the nation toward more industrialization. In 1869, the railroad tracks connecting the East and West Coasts were finally completed, helping to create a single nation-wide economy. The mining of coal, the primary fuel of the late nineteenth century, drew more workers, as total output of coal in the United States grew from 8.4 million short tons in 1850 to 40 million in 1870. Pennsylvania and Ohio, important areas for coal mining, increased their immigrant communities, notably attracting people from Wales, an area of the United Kingdom with a long mining tradition. By 1870, Ohio had 12,939 inhabitants born in Wales and Pennsylvania had 27,633, so that these two states were home to over half the nation’s Welsh immigrants. Immigration continued to climb through much of the third quarter of the century, with people from Germany and Ireland making up most of the new arrivals. For the first time, though, immigrants from China, pushed by political and economic problems in the home country and by opportunities created by the California gold rush and jobs on a railroad that was expanding across the country, began to enter the United States in significant numbers. From 1841 to 1850, only thirty-five newcomers to the United States came from China. During the 1850’s, this figure shot up to 41,397. The numbers of Chinese immigrants reached 64,301 between 1861 to 1870 and then almost doubled to 123,201 between 1871 and 1880. Chinese immigration began to drop following the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, decreasing to 61,711 between 1881 and 1890 and continuing to drop in the following decades. The railroads encouraged settlement of the farmlands of the Midwest and made possible the shipment of crops to the spreading cities. Scandinavians were among the immigrant groups that arrived to plow the newly accessible lands. Minnesota held 35,940 people born in Norway, or close to one third of America’s Norwegian immigrants by 1870. Minnesota was also home to the secondlargest population of Swedes in America, with 20,987. Another midwestern state, Illinois, had attracted 29,979 Swedes by 1870. Another 10,796 Swedes had settled in Iowa, adjoining Illinois on the northwest and just south of Minnesota. About two-thirds of America’s Swedish-born population could be found in Illinois, Minnesota, and Iowa. Late Nineteenth Century A major technological development that contributed to the increased flow of immigrants was the shift from sailing vessels to steam-powered ships. Prior to the Civil War, the overwhelming majority of immigrants crossed the Atlantic Ocean in sailing vessels, but this changed shortly after the war, making oceanic travel faster, cheaper, safer, and more comfortable. Europeans willing to travel in steerage class could cross the Atlantic for as little as twenty-five dollars. Companies that owned the steamships drummed up business by actively recruiting people in Europe to go to America. During this same period, the ethnic mix of immigrants was changing. By this time, Italians, Poles, Greeks, Slavs from the Balkans, and, in particular, large numbers of Jews from eastern Europe were making up the bulk of immigrants to the United States. As with the Irish before the war, members of each of these groups tended to cluster together in ethnic enclaves in the cities and towns where most of them settled. It was not uncommon for American employers seeking workers to contract with members of these communities to get them to pass the word to their fellow countrymen in their homelands that jobs were available. Twentieth Century The outbreak of World War I in 1914 put a stop to the great flood of immigration. Meanwhile, however, that flood had engendered a backlash among many native-born Americans. Aside from laws specifically prohibiting Chinese immigrants on the West Coast, the first comprehensive immigration legislation was passed in 1891. This law created the Bureau of Immigration within the Department of the Treasury and sought to prohibit immigrants that suffered from disabilities. It was only after World War I, however, that group restrictions were imposed to discourage immigration from countries other than those of western and northern Europe. A major exception was made for Mexican agricultural workers, who were brought into the United States on a seasonal basis under the bracero program begun in 1943. It was never intended that these workers would stay permanently in the United States, and they were carefully policed and returned to Mexico at the end of their contractual periods. In addition, the lack of employment opportunities during the Great Depression years of the 1930’s ensured that few would want to come.