can

CDSA 2015

St. Pierre

Capitalist Communication

A few months ago on the Did I Stutter blog, which you should all check out by the way, my colleague Zach Richter wrote a post entitled “Rewilding the Stutter” arguing that stuttering in all its unruliness should be conserved rather than trimmed neat and domesticated. A member of our community, someone who is not exactly on board with our radical crip politic, wrote in the comments that, rather than being like an organic root structure,

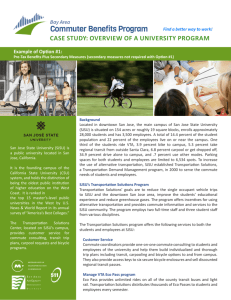

“Speech is like a city; . . . you plan and construct words when speaking. When stuttering you’re trying to speak. The metaphor maybe more like the Long Island Expressway at rush hour.”

This was a fascinating comment. Not only because there is something so phenomenologically apt about it (stuttering can often feel being caught at rush hour), but also because I believe it can tell us much about the relationship between capitalism and communication.

My response to this individual was this: “There are times when speech is certainly just a commute, a way to get from point A to

B. However, it would be sad if speech, like our lives, is never anything but a commute.” I would like to think a little more this morning about communication as commute, and the ways in which our formulations of communication are not simply complicit with modes of capitalist labour, but prefigure and constrict possible actions and ways of existing together with others.

Is speech really like a city? This implies and gives communicative priority to linguistic structures (to logos)—to the proper aligning of roads or channels as they meet

1

CDSA 2015

St. Pierre

(sometimes violently) at intersections. Speech as a city, as building, implies language as a utilitarian order (a view, incidentally, to which Marx also ascribed), that maximizes the flow of linguistic, sonorous vehicles transporting ideas between the minds of liberal capitalists.

Here it is worth noting that the modern usage of

“communication” comes, as John Durham Peters argues, from

Locke with etymological roots of both transmitting ideas between interior minds as well as transporting commercial goods. “Communication” has always been linked to economics.

The Lockean anxiety around both of these ventures is that of protecting the message or commodity during its voyage into the public sphere. Both the shipment of iron and the words uttered from mouth to ear cannot suffer corruption: just as the amount of iron sent must match what is received, so—for Locke’s rickety communication to be successful—must the idea sent be identical to that received. As a perfect symmetry, communication becomes a distinctly technical problem to be solved. Since meaning is interior—that is, existing within the heads of atomistic selves—the public sphere and the material signs that must venture into its domain are threats for liberalcapitalism; threats that must constantly be surveilled and managed.

Within this formulation, understanding, meaning, and communication are all terribly fragile. Yet the curious fact of communication is that despite being hollowed out by liberalcapitalism and rendered a problem, we increasingly overload the apparatus of communication. We demand much of it in our neoliberal and post-industrial society pinned together by the

2

CDSA 2015

St. Pierre exchange of information and the production of communicative

(and therefore productive) subjects. We demand much of it in our globalized and multicultural world wherein alterity is negotiated and managed through “understanding” and

“communication.” This fragile equation of transcending solitary subjectivity was doomed from the start. I suggest that the increasing exclusion of non-normative communicative bodies today can be read, at least in one regard, as a deferral of the problem of “communication” itself—a problem not simply of a concept but of a material-semiotic system thoroughly invested with capital.

However, I digress.

It is the consideration of communication as the shipment of ideas that renders the act of communication a commute. This can be filled out in several ways. For example, the space opened up by capitalist communication (including the start and end points) is predefined. The present is non-productive. The only thing one can experience during a commute is a delay or breakdown. Or perhaps better, jams and detours are only ever annoyances during one’s daily commute that is entirely instrumentalized, prefigured, and marked by a time running out.

Not only is there no space and time for disability within capitalism—for bodies and meanings that slip sideways, grow together, and take on a life of their own—but the suppression of such energies is necessary for the instrumentalizing materialsemiotic system of capitalism to survive. Zach Richter, again on our blog, suggests that “Word economy, a series of values placed on to speech, is a necessary labor for speech to perform

3

CDSA 2015

St. Pierre in integrating the subject within a diverse set of social forces”

(“Stuttering Anxiety and Fluency”). A congruence of singular meanings and singular/clear voices and bodies is produced and maintained by Taylorist disciplinary practices.

This terrain has shifted somewhat within post-industrialism— through modes of affective and “virtuosic” labour that privilege creativity and complexity—yet not as far as many would perhaps think. That is, often within language economies the communicative act itself becomes productive in affective and relational ways. However, a) alongside Lazzarato I believe the idea of language economies or “cognitive capitalism” has been considerably overblown and b) one must ask seriously what kind of communicative subjectivity is assumed for these productive transformations to even get off the ground.

In any case, we severely restrict the possibilities of our crip politics when we communicate as commute and aim simply for

“understanding”—as if crip meanings could be singular, as if ferrying thoughts between minds is in any way congruent with our complex ways of living together. Jay (Dolmage) reasons that meaning itself is crippled, in need of assistance to be carried across (Disability Rhetoric 103), and this, I believe, offers a transformative alternative to communication as commute.

Communication is always impure, partial, and embodied. It is a complex ethic of co-dependent care with attention to bodies and meanings that are birthed within these interactions. Peters suggests that in certain contexts “what might be called a failure to communicate is more often a divergence of commitment or a deficit of patience” but perhaps, against the conceit of capitalist communication, this is always true. Living into a crip communicative ethic—while resisting the sirens of liberal-

4

capitalist communication—is an important yet daunting challenge for our community. But really, who better?

CDSA 2015

St. Pierre

5