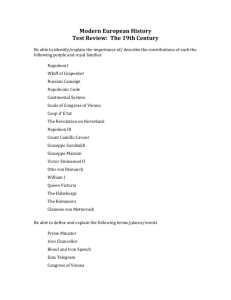

Architecture in Vienna

advertisement

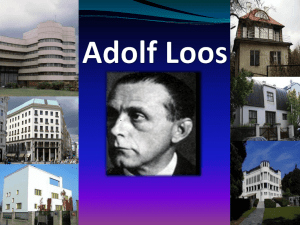

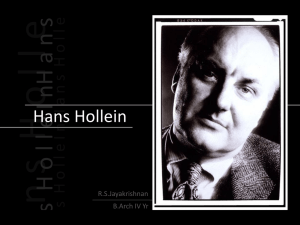

The rights to the use of this text are owned by WienTourismus (Vienna Tourist Board). The text may be reproduced in its entirety, partially and in edited form free of charge until further notice. Please forward sample copy to: Vienna Tourist Board, Media Management, Invalidenstrasse 6, 1030 Wien; media.rel@vienna.info. No responsibility is assumed for the accuracy of the information contained in the text. Author: Andreas Nierhaus, Curator for Architecture, Wien Museum Status as at January 2016 Architecture in Vienna Vienna’s 2,000-year history is intricately woven into the city's modern-day fabric. The layout of the city center goes back to the Roman settlement and the road network of the Middle Ages; Romanesque and Gothic churches define the character of the streets and squares as much as the palaces and townhouses from the Baroque period. If the Ringstrasse was the ultimate expression of a modern metropolis in the nineteenth century, extensive residential complexes in the outer districts set the tone for the twentieth century. Currently, a number of large-scale urban planning initiatives are being implemented, and distinctive structures designed by star architects are redefining Vienna’s skyline. Because of its standing as the imperial residence and a center of power in Europe, the Austrian capital was a focus of international attention for centuries – a role the city was fully aware of. This prompted the development of an outstanding building culture, and even today only a few other cities worldwide can boast a similar concentration of valuable architecture. Over the years the city has made a consistent effort to integrate these historical highlights as well as open the way for some spectacular new buildings. The fastest-growing major city in the German-speaking region is today setting new global standards, particularly in residential construction. Conservation of established structures, revealing the historical layers of the city’s built environment, and the dialogue between old and new have been constants in Viennese architecture. The pinnacle of architecture in the Middle Ages: St. Stephen's Cathedral The oldest architectural landmark in Vienna is St. Stephen's Cathedral. Under the Habsburgs, who had a defining impact on the appearance of the city from the late thirteenth century until 1918, the cathedral was gradually expanded as a sacred monument to the ambitions of the ruling dynasty. Affectionately dubbed the “Steffl” by the Viennese, the 137-meter high south tower completed in 1433 is a masterpiece of European late Gothic architecture. For decades it was the tallest stone construction in Europe and it remains the undisputed focal point of the city today. 1 Imperial capital of the Baroque Vienna’s ascent to the ranks of the great European capital cities began in the Baroque period. Among the most important architects of this time were Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach and Johann Lucas von Hildebrandt. A string of summer palaces sprang up beyond the city walls, including the Schwarzenberg Garden Palace (1697-1704), and Prince Eugene of Savoy’s Belvedere palaces (1714-22). Prince Eugene’s winter palace (1695-1724; today a branch of the Belvedere) and the Palais Daun-Kinsky (1713-19; today the Im Kinsky auction house) are among the most important city palaces. The Emperor himself expanded the Hofburg with the construction of the court library (1722-26) and the winter riding school (1729-34). But building churches and monasteries was even more important to the Habsburgs. Fischer von Erlach’s Karlskirche (Church of St. Charles), erected outside the city walls between 1714 and 1739, is one of the most important works of European Baroque, with its beautifully executed, formally complex façade. The colorful interiors of churches like the Peterskirche (1701-22) are testament to the period’s ambition to combine architecture, painting and sculpture. A city becomes a metropolis: the Ringstrasse era Plans to extend the hopelessly overcrowded city had been considered from the Baroque period onwards, but it was not until 1857 that Emperor Franz Joseph ordered the city wall fortifications to be demolished so that the historic center could be connected to the outlying suburbs. Opened in 1865, the Ringstrasse is the most significant showpiece boulevard in Europe, and an architectural and urban planning achievement of the highest order. The buildings have retained almost all of their original glory, providing an authentic impression of a nineteenth-century metropolis. True to the tenets of historicism, the architecture of official public buildings on the Ringstrasse was intended to match their purpose: the classical Greek forms used by Theophil Hansen for the Parliament (1871-83) represent democracy, the Renaissance style of Heinrich Ferstel’s university building (1873-84) refers to the blossoming of humanism, and Friedrich Schmidt’s Gothic City Hall (1872-83) stands for the civic pride of the Middle Ages. But the buildings of the imperial court still dominate the Ring – Eduard van der Nüll and August Sicardsburg’s State Opera (1863-69), Gottfried Semper’s and Carl Hasenauer’s Burgtheater (1874-88), their Kunsthistorisches Museum and Natural History Museum (1871-91), and the New Hofburg (1881-1918). At the same time, the Ringstrasse was the preferred place of residence for the mostly Jewish upper class. Families such as the Ephrussis, the Epsteins, and the Todescos built luxurious palaces, making it clear that they were taking the cultural lead in Viennese society. The 1873 World’s Fair gave the new Vienna an opportunity to present itself to an international 2 public, and many hotels opened on the Ringstrasse including the Hotel Imperial and today’s Palais Hansen Kempinski. The laboratory of modernism: fin-de-siècle Vienna One of the last buildings completed on the Ringstrasse was Otto Wagner’s Postsparkasse (190306). Its ornament-free façade, decorated only with functional aluminum bolts, and the use of glass in the cashier’s hall make it an icon of modern architecture to this day. Otto Wagner represented the spirit of departure at the turn of the century like no one else. His commuter railway stations elevated the city’s public transport network to the status of architecture, and the church he built at the Steinhof psychiatric hospital is considered to be the first-ever modernist church (1904-1907). Wagner’s unswerving focus on the function of a building – as he famously said, “What is impractical cannot be beautiful” – influenced a whole generation of architects and turned Vienna into the laboratory of modernist architecture. Besides Joseph Maria Olbrich, who built the Secession (1897-98), and Josef Hoffmann, architect of the Purkersdorf Sanatorium (1904) on the western outskirts of the city and founder of the Wiener Werkstätte (1903), the most important of these was Adolf Loos – the Looshaus on Michaelerplatz made architectural history when it was unveiled (1909-11). The storefront level is extravagantly clad in marble, in absolute contrast to the plain façade above – making the “nakedness” of the upper floors even more obvious. This functionally motivated statement was as provocative as Loos’ essay on cultural criticism, “Ornament and Crime”, which had a huge influence on twentieth-century architecture. Loos was effectively blacklisted from being awarded public contracts. His most important works therefore include villas, residential projects and stores such as gentlemen’s tailor Kniže am Graben (191013), maintained in its original condition to this day, and the restored Loos Bar (1908-09) off Kärntnerstrasse. Between the wars: international modernism and social housing With the collapse of the monarchy in 1918 Vienna became the capital of the new, rump state of Austria. In the heart of the city center, architects Theiss & Jaksch built the city’s first high-rise, an exclusive apartment building at Herrengasse 6-8 (1931-32). To tackle the desperate public need for housing, the social-democratic city government embarked on a building program that was unique worldwide, creating 60,000 apartments in hundreds of residential complexes all over the city within just a few years. Not least among these is the well-known Karl Marx Hof (1925-30), designed by Karl Ehn. The international Werkbundsiedlung, an alternative to the multi-story apartment buildings, opened in 1932: 31 architects from Austria, France, Germany, Holland, and 3 the USA participated in the project, which showcased models for affordable living in leafier surroundings. Containing houses by Adolf Loos, André Lurçat, Richard Neutra, and Gerrit Rietveld, the Werkbundsiedlung counts among the most important documents of modern architecture in Austria. It is currently undergoing an extensive program of renovations. Modernism also found expression in a number of notable villas built during this period. Josef Frank’s Beer house (1929-31) is a typical example of the refined Viennese interiors of the inter-war years, while the austere design and radical aesthetic of the Stonborough-Wittgenstein house (1926-28, today the Bulgarian Cultural Institute), designed by architect Paul Engelmann and philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein for Wittgenstein’s sister Margarete, is unparalleled in the architecture of the period. Expulsion, war and reconstruction Following Austria’s annexation to the German Reich in 1938, many Jewish builder-owners and architects – who had played a vital role in taking Viennese architecture to such a high level – were driven out of the country. Vienna was largely spared from Nazi-era construction projects, except for the six reinforced concrete flak towers built by Friedrich Tamms between 1942 and 1945 that still leave their mark on the urban skyline as reminders of those times. The years following the end of the Second World War were defined by rebuilding efforts in the badly bomb-damaged city. Aesthetically, pragmatism was the defining feature of the architecture of this period, although attempts were also made to reconnect with the period before 1938 and to pick up on international trends. Roland Rainer’s Stadthalle (1952-58), the Wien Museum on Karlsplatz built by Oswald Haerdtl (1954-59) and the 21er Haus (1958-62) by Karl Schwanzer are among the most important buildings of the 1950s. Young blood From the 1960s a new generation sought alternatives to the reserved modernism of the reconstruction years. With their visionary designs, and their conceptual, experimental and usually temporary architectural works, interventions, and installations, Raimund Abraham, Günther Domenig, Eilfried Huth, Hans Hollein, Walter Pichler, and the groups Coop Himmelb(l)au, HausRucker-Co, and Missing Link rapidly attracted international attention. Although exponents initially produced more drawings than buildings, Vienna had a major impact on the international postmodern and deconstructivist movements of the 1970s and 1980s. Hollein’s futuristic Retti candle shop (1964-65) on Kohlmarkt, and Domenig’s biomorphic Zentralsparkasse building (1975- 4 79) in Favoriten are among the earliest examples, followed later by Hollein’s Haas-Haus (1985-90), the Falkestrasse loft conversion (1987-88) by Coop Himmelb(l)au and Domenig’s T-Center (200204). Foreign commissions awarded to Domenig, Hollein, Coop Himmelb(l)au and architects Ortner & Ortner (previously members of Haus-Rucker-Co) finally put new Austrian and Viennese architecture on the map. MuseumsQuartier and Gasometer Since the 1980s one major focus of architecture in Vienna has been new construction within the historical urban fabric – now unequivocally considered an area that boasts a high quality of life. Among the projects best known internationally is the MuseumsQuartier (competition 1987, built 1998-2001) at the former imperial stables, designed by Ortner & Ortner. It is one of the biggest cultural complexes in the world, containing a range of institutions including the mumok - Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, the Leopold Museum, the Kunsthalle Wien, the Architekturzentrum Wien and the Zoom Children's Museum. Following a drawn-out and controversial planning phase, an architectural compromise between old and new was finally achieved. The MuseumsQuartier has become overwhelmingly successful as an urban cultural arena, attracting four million visitors in 2012. In a city as strongly infused with history as Vienna, the dialog between old and new is always on the architectural agenda, and it also characterizes the conversion of the Gasometers in Simmering (1999-2001) masterminded by Coop Himmelb(l)au, Wilhelm Holzbauer, Jean Nouvel, and Manfred Wehdorn. This project created new living space as well as reinterpreting a historic monument to the industrial past as a symbol of urban development. New districts For the past few years planning has focused on Vienna’s major train stations and the areas around them, where key infrastructure upgrades have gone hand-in-hand with the creation of large new inner city residential and retail districts. Flagship projects include Vienna's new Hauptbahnhof or central station (2010-14) and flanked by the office blocks of the Quartier Belvedere and the new apartment buildings and schools of the Sonnwendviertel. A regeneration project at the site of the former Nordbahnhof station is creating 10,000 apartments and 20,000 jobs, while the biggest passive house project in Europe, Eurogate, is under construction at the Aspangbahnhof station. The site of the Nordwestbahnhof station is expected to be redeveloped as a residential and commercial district from 2020. However, the biggest residential development currently under way is located on the north-eastern fringe of the capital – by 2028 places to live and work for a total of 5 40,000 people will be created in Seestadt Aspern. Special government grants paved the way for high-quality yet affordable housing – an aspect of the capital’s approach to urban planning that has attracted plaudits worldwide. But it’s not just residential construction projects, the city also invests heavily in scientific and academic facilities. Examples include the campus for Europe’s largest business university which opened in the Prater, one of Vienna’s large green spaces, in 2013. The spectacular buildings around the central square of the Campus WU have inspired heated debate on the status quo in contemporary architecture and were designed by an international band of architects (Hitoshi Abe, BUSarchitektur, Peter Cook, Zaha Hadid, NO MAD Arquitectos, and Carme Pinós). Reaching for the skies A number of architects from different countries have added high-rise buildings to Vienna’s skyline in recent years, often in uneasy competition with the iconic outline of St. Stephen's Cathedral. Massimiliano Fuksas's Twin Tower complex in the Wienerberg district, featuring 138-meter and 127-meter towers, is visible for miles around, while in contrast Jean Nouvel’s monolithic, 75-meter Hotel Sofitel on the Danube Canal (2007-10) is a response to the specifics of its urban environment, its top floor offering new perspectives on the historic city center. Dominique Perrault’s DC Tower 1 (2010-13) is also located next to water, in the Donau City – the high-rise district whose growth has reflected the capital’s expansion north of the Danube since building began there in 1996. Perrault’s slim, striking tower with its zig-zag vertical pleats reaches beyond all of the boundaries previously broken by buildings here: visitors to the bar on its top floor can enjoy the highest view of Vienna. At 250m, DC Tower 1 is Austria’s tallest building and almost twice the height of St. Stephen's Cathedral – meaning that Vienna has gained a new truly unmissable architectural landmark. But only time will tell whether it has the potential to become a symbol of the new Vienna. One thing is certain: there are still many exciting chapters to be written in the architectural history of Vienna, where the history of Europe lives on in the present and new buildings always engage in an exciting dialog with the city’s rich heritage. Further information: a brochure entitled Architecture from Art Nouveau to the Present is available from the Vienna Tourist Board and online at www.wien.info/media/files/guide-architektur-inwien.pdf. 6