The name I was born with is Christina Fear. My mother taught at

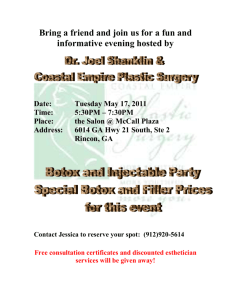

advertisement

The name I was born with is Christina Fear. My mother taught at Rincon School in Prado at the end of the 19th century. She died when I was a few years old and my father went on to marry the mother of a teacher at the same school a few years later! Then I went on to attend Rincon from the age of 5 through 8th grade. After that was Corona High School, Pomona College, and back to Prado to teach at…[heavy sigh, making a face]- not the same school. They closed it down when there were only two students left to teach in 1920. Which is hard to understand when you consider that just a few years later in 1922, I ended up teaching FORTY-FOUR students in NINE grades at the combined Rincon-Prado School! About that time, I married a boy who went to Corona High School with me - Harold Barnett. Some while later I divorced him and married Giruaurd Desborough, before dying in 1988 and ending up at some cemetery in Glendale – don’t ask me why! Because my heart was always in Prado and with the school I loved – The Rincon School of my youth. I arranged reunions here in Corona for years, collecting stories from my old friends, and then writing a manuscript on the history of Prado, and another on the history of Rincon School. Why did I write about my school? Because Rincon School was something special. Really special. The Spanish meaning of Rincon is of a corner or nook, a place of privacy, a lurking place and that, I think described us perfectly. A small, private corner, a place lurking betwixt and between the pages of history as California transformed from rule by the Spanish-speaking ranchers, to rule by English-speaking ones. At first glance, perhaps Rincon School might not seem so different than others in California. We were a mix of English speakers and Spanish speakers. But what made us unique is that the Spanish speakers were not the field workers that they were in Corona. Most of my classmates who were Spanish speakers were the grandchildren of the old Spanish rulers of California. Descended from an aristocracy that had ended not 50 years before. Leonardo and Inez Cota owned a mansion in Prado. Leonardo’s grandfather of the same name had been cousin to the last governor of Alta California who had married the daughter of Bernardo Yorba, one of the most successful ranchers in California with 35,000 acres, and for whom Yorba Linda is named. The Cota mansion in Prado was one of the best known homes in southern California in the late 1800s, with guests arriving from as far south as San Diego and all the way up to Monterey. It was not uncommon for as many as 50 unexpected guests to arrive for a stay of a week – or even a month. Fifty!! Can you imagine entertaining 50 unexpected guests? For a month! Guests would bring violins and guitars for the nightly dances until dawn, while in the daytime there would be horse racing and gambling. I cherish my memories of Senor Leonardo Cota. He was the most courtly gentleman it has been my good fortune to know. One of the last of the Spanish grandees. The Serrano family also came from wealth. Don Leandro Serrano arrived in the neighborhood in the 1820s, migrating from his family’s ancestral home – 10,000 acres near what is now El Toro Marine Air Station. I was privileged to play with the grandchildren of these two families, growing up. One of my schoolteachers, Lottie Lou Adams, lived with the family of one of Leonardo’s sons and was invited to dances at both the Cota and Serrano ranches. Lottie later told me of parties at the Serranos where the men of the family played string instruments and one of the girls would play the enormous organ that Grandma Serrano had bought in 1901. She also attended elaborate dances with the family held in the upper floor of the Rincon Hotel, where the women wore ball dresses with long trains that they draped over an arm when they danced. On Friday afternoons they would travel to Riverside for weekend parties. The multicultural experience that I enjoyed in Prado was one that I think very few Californians – yesterday or today – can lay claim to. When I was five I began my years at Rincon School. And after just a few weeks, according to my family, I came home with a distinctly Spanish accent! Not because of our teachers – young women of English ancestry who stayed with us a year or two – then usually leaving at the end of a term to get married. But my playmates included NINE Serrano children! Pancho was a favorite pal of mine. His mother would always have fresh tortillas for me, my little sister, Dorothy, and Pancho’s brothers, sisters, and cousins we stopped by his house on the way home from school each day! But all of my friends weren’t of Spanish descent! One of my good friends was Winifred West – whose father, like my own, was also a well-off rancher in Prado. When Winifred first started school she was five and lived several miles away – much too far to walk. So what did her parents do? They tied her onto a horse every day to get her there on her own! “Scotty” loped down the long dirt road; turned sharply east at the Serrano home, pushed the schoolyard gate open with his nose; jumped the ditch, and patiently stood at the school steps until someone untied his rider! Our school building was beautiful. There were woodpeckers near the eaves and owls in the belfry. The classroom had a wood-burning heater in one corner and a towering organ. Many of our teachers began the day with a rousing ‘sing along.’ My favorite song, Juanita, was seldom permitted because all the boys plus me would BELLOW out the chorus as: Wah-wah-wah-KNEE-tah.’ If teacher risked playing the organ, we really ROARED. One of the pleasures of grammar school was passing notes back and forth, and hopefully not being caught at it. I recall passing a note stuck between my bare toes to Henry Sandoz. Yes, if we could get away with it, my sister and I went barefoot to school when it was warm out! We’d ditch our shoes and stockings on the way to school, enjoying the luscious feel of the dust scrunching between their toes. Soon, someone would tattle and it was back to shoes. When it was time for lunch, teacher would always read a story with a cliffhanger so that we would be sure to come back when she rang the bell to return! A favorite spot to eat lunch was outside the fence behind the stables where the great pepper tree’s branches meant teacher couldn’t see us. Juanita Willis and I ate our lunch high on one of the mammoth branches of this pepper tree. There was room for four and we sometimes broke down and invited two schoolmates to join us. When Hortense Ashcroft was our teacher in 1908, we often played baseball at lunch. She was good at EVERYTHING - even to completely out-batting, out-pitching, and, in many instances, even out-running the big boys! And you haven’t really lived unless you were in the Chino Hills to see her cut a reluctant calf out of the herd! With other teachers, we usually made up our own games that involved running around as fast as we could – variations on tag. But one day, instead of playing games, I got into a fight. Sort of. Manuel Villalobos was a young man from Mexico living with the Serranos to learn English. It was hard for him to adjust to being in grade school with children, when he had been a high school student in Mexico. It made him super sensitive. He always wore a hat and suit with buttoned vest so his ‘badge of manhood’ – a gold chain and watch – could stretch across his chest. This day he and I were ‘spitting mad.’ He made out as though he were about to kick me. I whipped out my trusty hat pin and pricked him with it – a drop of blood actually appeared! He ran to a tree and tore off a long branch and confronted me. In the meantime I had grabbed up a hoe. There we stood glaring at each other weapons at the ready…then we started to giggle. For the first few weeks that we had Bess Adams for our teacher in 1911, it seemed like we were in for trouble. She loved Latin culture – later she would go on to establish the Padua Hills Theater. When she came to us it was with such things firmly in her mind as ‘under privileged,’ ‘minority group,’ and ‘racial prejudice.’ Being brilliant, she soon realized that she was about to divide us (for the FIRST time in our lives) into two truly just such groups. She ‘snapped out of it’ and we had one of the most pleasant and profitable years of our existence. The last day of school always meant a picnic on the Santa Ana. Here’s a bit from my diary: “June 6, 1913: The picnic wagon arrived at 9:05. Millie Strong and Mrs. Henry were on our hay wagon. I took Mary Pine to my secret patch of blackberries where we stuffed ourselves with berries, got stung by nettles, scratched up, our stockings torn and our dresses stained and torn. Mrs. Strong mended our clothes. It was fun!” Rincon School was more than fun. It provided us, its students, with an experience in California history like no other; we lived in a corner or nook that it is time we, of Corona, shone a light on – because our history here is even grander and nobler than has yet been acknowledged. I dismiss this class! Please remember your homework assignment, which is to read my manuscripts in the Heritage Room at the library!