Senior Seminar History Research Paper

advertisement

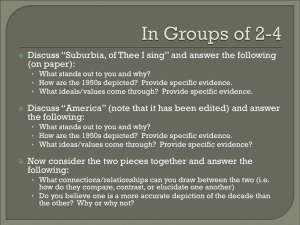

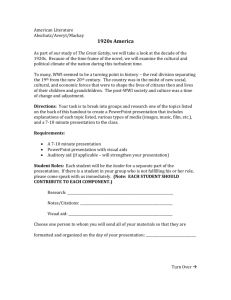

Miller 1 Deanna Miller HIST 490: Advertising in Modern America Dr. Henold Final Draft Fall Semester 2013 Keeping Up With The Joneses: An Analysis of Advertising Techniques in the 1950s An advertisement for a Hoover vacuum depicts four well-dressed women circled around the vacuum, gazing at it adoringly – almost worshiping the machine. “Announcing the New Hoover,” is spelled out in large font on the page.1 When you put together the image with the words, the advertisement seems almost like a baby announcement and evokes the feeling of looking at a newborn; this advertisement is portraying the inanimate object as a member of the family. Another advertisement for a General Electric washer displays a young woman next to the appliance, smiling in admiration of the machine, much like the women in the first advertisement. She states that she knows the joy of “quick-clean washing,” thanks to her General Electric washer.2 Interestingly, these two advertisements use the same advertising technique but are published almost twenty years apart. Introduction 1 2 See Fig. 1 See Fig. 2 Miller 2 After World War II, Americans were experiencing an age of abundance that had not been seen since the beginning of the 20th century and not ever to such an extent. In the 19-teens, the world experienced its first major world war on a scale never before imagined. Then, in the 1920s, the U.S. experienced an age of abundance that they never had before, though not to the same degree as we see in the 1950s. During the 1930s, the United States was recovering from the impact of the Great Depression; families were focused on finding work and affording the necessities during hard economic times. In the early 1940s, Americans were concentrated on the war effort; unnecessary spending was frowned upon and people were, instead, encouraged to support the troops by buying war bonds. Consumers, since the end of the 1920s, were taught not to participate in extravagant spending and, after World War II, it had become so ingrained in their behavior; advertisers faced a new challenge in finding another way to market their products that would teach families it was okay to spend their money on things they couldn’t before. During the 1950s, advertisers became masters at manipulating their audience to encourage them to become “good consumers” by using different methods like visual clichés, leisure, ensemble, trendsetting, and the parable of the first impression. However, these methods weren’t new to the world of advertising. Roland Marchand, author of Advertising the American Dream, has found extensive evidence that these same methods were used in advertisements of the 1920s. The goal of this paper is to understand how advertisers in the 1950s used ad techniques from the 1920s to teach consumers how to buy in a time of prosperity that Miller 3 had not been occurred for roughly twenty years. This paper also plans to discuss what exactly these advertisements say about consumers during this time. In my research, I found that a lot of analysis available on advertisements concentrates on particular decades, but does not look to see how that decade might have been affected by other advertising techniques in earlier periods. I noticed this specifically in Roland Marchand’s Advertising the American Dream, which focuses on the 1920 through the 1930s, and Thomas Hine’s book, Populuxe, which focuses on the 1950s and early 60s. However, I have found that while both authors have compiled persuasive evidence for their arguments, Thomas Hine fails to understand the history of the advertising methods he discusses in his book. Hine looks at advertisements and consumer culture of the 1950s by itself and does not look into the history of advertising or any earlier instances of these techniques. Lit Review and Historiography The 1920s “actually began with an economic whimper; the transition back to peacetime after World War I was a difficult adjustment…which caused a short but sharp recession in 1920-21.”3 However, after an increase in wages the economy was pulled out of the brief recession and experienced a growing economy by 1922. The rise of corporate advertising and new mass-production industries helped to increase the economy of the 20s. In fact, advertising increased from 2,480 million in 1920 to Shmoop Editorial Team, "Economy in The 1920s,"Shmoop University, Inc.,11 November 2008, http://www.shmoop.com/1920s/economy.html 3 Miller 4 2,600 million by 1925.4 Advertisers accomplished this by redefining “the source of abundance from the fecund earth to the efficient factory” while the factories themselves increased the amount of product they were selling.5 The consumer culture the ad men promoted was the accumulation of items, not the possession itself, gave an individual the appearance of abundance or high status.6 Roland Marchand, author of Advertising the American Dream, offers insight on the marketing and advertising industries in the 1920s and 30s by analyzing the advertisements of the time. Marchand makes a compelling argument for the different methods used by the advertisers and the intended effect these ads were supposed to have on the audience. The ad men used schemes like ensemble, trendsetting, modernity, the fear of first impression, and visual clichés to entice their audience into purchasing various goods and services. However, these manipulation tactics can also be found in the advertisements of the 1950s, discussed in Thomas Hine’s book, Populuxe, which will be analyzed below. Another source of information on the 1920s comes from Stuart Ewen’s book, Captains of Consciousness, which discusses the origins of the advertising industry and consumer society in the early 20th century. The aspect of this book used for this paper is Ewen’s argument on the impact advertisers and businesses had on the consumer and how they tried to create new needs and ways of consumption in order to increase Douglas Galbi. Think! Communications Economics and Industry Analysis Blog. http://www.galbithink.org/ad-spending.htm. 5 Jackson Lears. Fables of Abundance: A Cultural History of Advertising in America. (New York, New York: The Perseus Books Group, 1994), 18 6 Ibid. 20 4 Miller 5 profits. Furthermore, Ewen describes how advertisements seemed to twist the reality of how financially and socially inaccessible their products were to people and how they shaped this reality to invent a new consumer culture that made the audience to feel desire for products that they didn’t necessarily want or need. Advertisers borrowed the methods of the 20s and reused them in the 1950s, because they had to find ways of advertising their agenda in a period of abundance. Reusing 1920 advertising methods alone would not accomplish this goal. The economy of the 1950s was much bigger than that of the 1920s; spending on advertising alone jumped from 2,480 million in 1920 to almost 12,000 million in 1960.7 There were more products to be sold, more consumer capital to tap into, and more images of the American dream to project to the audience. However, advertisers only knew the techniques that had been in the field since the 1920s. So they took this knowledge and applied it to the 1950s, but had to adjust it to get the attention of the consumers. During the Second World War, the economy was receiving the relief it needed. The employment rate decreased from 4.7% in 1942 to only 1.2% in the last year of the war.8 This is due to the fact that men were joining the army and becoming employed while women who did not join the war effort as nurses took the jobs they Douglas Galbi. Think! Communications Economics and Industry Analysis Blog. http://www.galbithink.org/ad-spending.htm. 8 Frank Hobs, and Nicole Stoops. Demographic Trends in the 20th Century. November 2002. http://www.census.gov/prod/2002/pubs/censr-4.pdf. 7 Miller 6 left behind in the factories. For the first time in a long time, families had an increased pay they didn’t have in the 1930s and early 40s. And when the soldiers returned, they came to an improved economy and raised wages that would increase their purchasing power. Suddenly, advertisers had a consumer base with so much potential they could tap into and they took advantage of that. Advertisement funding increased from 2,840 million at the end of World War II in 1945, to 5,700 million in 1950, rising continuously to 11,960 million by 1960.9 With the rise in money spent on advertising and the increased interest in the topic, advertisers had to become more creative in order to compete. The methods of the 1920s had worked so well but they couldn’t directly apply them; this was a new era with new technologies and ideals to be exploited. Thomas Hine’s Populuxe discusses the consumer culture of the 1950s and how it was shaped by advertisements, suburban neighborhoods, and societal standards. Hine unknowingly takes the methods discussed by Marchand and applies them to the 1950s culture, though he fails to mention that these various methods were used before. Hine discusses many of the same techniques that Marchand also mentions, such as ensemble, modernity, planned obsolescence, and style. However, this book combines these techniques and analyzes them with social culture of planned economies, otherwise known as suburbs. Douglas Galbi. Think! Communications Economics and Industry Analysis Blog. http://www.galbithink.org/ad-spending.htm. 9 Miller 7 Advertisers began to market wants and needs differently in the 1950s; they tried to illustrate the positives of consuming, instead of the negative aspects of not purchasing new goods. The advertisers also had to combat the idea that consumption was dangerous in the 1950s and that a new depression would not hit the United States economy. The impact of the Great Depression was still fresh in Americans’ minds and the fear of returning to that state must have been overwhelming. However, the economy after WWII was booming; more people were employed, wages had been increased, and more money was being spent on goods and services. Advertisers in the 1950s were dealing with a new economy and so they required new advertising methods. The post-war economy was booming and families were earning more than ever before.10 Higher incomes gave consumers an increase in spending power and they could afford more leisure items. Elaine May writes that “rather than putting money aside for a rainy day, Americans were inclined to spend it.11 ”However, advertisers had to teach consumers that, because the war was over, they should now be focusing on spending their money on goods and not saving it as they had been taught in the past. The advertisers wanted to create a conspicuous consumer, meaning they would spend money on acquiring luxury goods and services in order to display their socio-economic power. The majority of the target audience grew up during the Great Depression and their families could not afford to spend their Elaine Tyler May. Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era. (New York, New York: Basic Book Inc., 1954), 165 11 Ibid. 10 Miller 8 money on luxury items. Advertisers wanted them to feel that they should be purchasing these goods during good economic times and show them off to their friends and family. In fact, one major theme in the advertisements is that the owner of the object, usually a woman, was showing off their brand new, top-of-the-line appliance that they had the economic ability to purchase. This need to show off wealth was intensified in planned economies, or the suburbs. The population of those living in suburbs rose from 122.8 million at the end of the 1930s to 179.3 million by the 1960s.12 Within these planned economies, houses were almost identical, making it hard to stand out. Manufacturers capitalized on this and gave their customers a new way to stand out by offering their appliances in different colors and adding new technological aspects every year. These techniques were assisted by the suburban neighborhoods. After World War II, men were returning home to their lives before the war. With this rise in new married couples, the demand for housing increased. With the passing of the GI Bill, soldiers were given funds to attend college and purchase homes, and the increase in the amount and quality of roads allowed for families to live outside the cities and commute to work. These soldiers were “in dire need of about five million houses, as ex-GIs and their families were living with their parents or in rented attics, basements, or unheated Hobbs, Frank, and Nicole Stoops. U.S Department of Commerce, "Demographic Trends in the 20th Century." Last modified November 2002. http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/censr-4.pdf. 12 Miller 9 summer bungalows.”13 However, construction companies had found a cheap and efficient way to build houses on the outskirts of cities. Thus, planned communities were formed where houses were pre-planned and similar to each other. Elaine Tyler May’s Homeward Bound, and offers more information on 1950s suburban housing and culture by discussing the rise of the consumer-oriented advertising based on the suburban home. Suburban housing was designed with lower socio-economic families in mind, especially soldiers returning from the war. In fact, the GI Bill of Rights created a program that guaranteed insurance for mortgages and loans that helped soldiers and their families afford homes in the suburbs.14 Even the Cold War pushed the popularity of housing in the suburbs through scientific endorsement of the “defense through decentralization” rationale that “argued in favor of depopulating the urban core to avoided a concentration of residences or industries in a potential target area for a nuclear attack.”15 May also mentions the role that suburban housing had in fostering “traditional gender roles in the home,” which includes women being recognized as the main consumer in the family.16 The purpose of this paper is to connect and compare the works above, focusing on Advertising the American Dream and Populuxe, as well as concepts from other literature, to achieve a better understanding of the 1950s consumer culture. What Peter Hales. Levittown: Documents of an Ideal American Suburb. University of Illinois at Chicago. http://tigger.uic.edu/~pbhales/Levittown.html. 14 Elaine Tyler May. Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era. (New York, New York: Basic Book Inc., 1954), 169 15 Ibid. 169 16 Ibid, 171. 13 Miller 10 these books lack is a contribution to a bigger picture. Each of these books have analyzed a small period of time but have made no attempt to understand how these ideas fit into the 20th century as a whole. These books lack in mentioning how these methods and techniques effected other eras or how they might have been inspired by earlier times. I will apply the methods and information in each of these texts and apply them to 1950s advertisements. In the analysis portion of this paper, I will explain the advertising techniques in three different ways. First, is how the method was portrayed in Roland Marchand’s Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity. Second, I will discuss how Thomas Hine discusses the technique in Populuxe: The look and life of America in the ‘50s and ‘60s, from tailfins and TV dinners to Barbie dolls and fallout shelters . And last, I will add my analysis of the advertisements I collected from the 1950s. These techniques include, planned obsolescence, the ensemble, style and trendsetting, visual clichés, and the fear of first impression. Planned Obsolescence Planned obsolescence is something today’s consumers know very well. Technology is just not built to last anymore; things tend to break or need replacing after a short while. However, this concept has been around for quite a while. Marchand discusses the concept of obsolescence through fashion and the use of color. The fashion industry has been using obsolescence through trendsetting long before the 20th century, but Marchand argues that it increased in the 1920s when manufacturers Miller 11 and ad men picked up on this technique and applied it to the products they were selling.17 According to the documentary The Light Bulb Conspiracy, planned obsolescence is a concept that has been around since the early 20th century.18 In the early 1920s, a group called Phoebus emerged. This group was the world’s first worldwide cartel; its purpose was to control the production of light bulbs to make sure that they would have a profitable market. Manufacturers from the United States and Europe had begun to realize that their light bulbs, some of which were built to last at least 2,500 hours, were lasting too long. These companies figured out that if they kept creating products that lasted for so long, they were not going to make a sizeable profit. So, in 1925, Phoebus met and decided to form the “The 1000 Hour Life Committee,” which was committed to reducing the life of light bulbs.19 This committee pressured its members to create a light bulb that lasted no more than 1000 hours by threatening fines. By 1932, the cartel had succeeded; all member companies had created a light bulb that would not last as long as its previous models. The light bulb stands for new ideas and innovation but really was the start of planned obsolescence. The idea of planned obsolescence may have begun in the 1920s, but it didn’t become a popular method until the 1950s. In the 1920s, “mass-production made many Roland Marchand. Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity. (London: The Regents of the University of California, 1985), 132 18 Cosima Dannoritzer, The Light Bulb Conspiracy, Directed by Cosima Dannoritzer. Performed by Mike Anane and Michael Braugnart. (2010) 19 Ibid.; Helmut Hodge, an historian in Berlin found proof of the cartel and the committee, as well as a few of the companies involved. 17 Miller 12 goods widely available, prices fell and many people started shopping for fun rather than need.”20 This all came to a halt when the Stock Market crashed in 1929. People no longer focused on buying luxurious goods, but more on food and work. The first time the words “planned obsolescence” were used was actually during the Great Depression. Many economists tried to figure out how to get the United States economy back to where it was before the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and Bernard London, an economist, suggested something radical. London proposed that making planned obsolescence compulsory by law would end the Great Depression.21 London stated that all products would be given a lease of life where they would be considered “legally dead,” and at such a time consumers would turn them over to a government agency to be destroyed. Of course, this proposal was never considered and, though the idea was used in the 1930s during the Great Depression, the term was not used again until the 1950s. A few years after the end of the Second World War, the United States was experiencing an era of progress and prosperity. By this time, advertisers were getting smarter. Instead of forcing planned obsolescence on their audience, they became clever in their marketing and began to seduce consumers with it. Brooks Stevens, whom the documentary The Light Bulb Conspiracy called the apostle of planned 20 21 Ibid. Ibid. Miller 13 obsolescence, created many products with that method in mind.22 Stevens’ designs contained speed and modernity and believed that these designs should inspire a consumer to purchase the good. The documentary argues that “design and marketing seduced consumers into always craving the latest model,” and Stevens’ claimed purchasing a good was at the discretion of the consumer. However, the psychological tactics used by advertisers were manipulative and the actions taken by manufactures leave the consumers with no choice but to comply with planned obsolescence. Advertisers played on their audiences’ emotion to achieve this. The memory of the Great Depression is still present and the tragedy of war a not so distant past. This manipulation, however, did not just apply to technology. Many advertisers pulled from the idea of planned obsolescence of technology and inserted it into advertisements for other goods. Thomas Hine, like Marchand, looks at obsolescence through fashion and color. Hine states that “the increased importance of colors [in the 1950s] meant everything changed more often. Populuxe refers to many advertisements that incorporated color, from ads about refrigerators and stoves, to ads on bathroom furnishings. You could match all of your kitchen appliances, your furniture, and more. There were even advertisements for colored toilet paper so that even that could match the color scheme of your bathroom. Much of this is taken from the fashion industry; advertisers made women the trendsetters of appliances and furniture. Women have been victim to 22 Ibid. Miller 14 fashion for much of history so applying trends and style to their appliances and furniture seemed second nature to them. The Ensemble Planned obsolescence does not just apply to technology, but to the products’ style and fashion trends as well. Roland Marchand states that the “crowning achievement of advertising’s emphasis on color, beauty, and style in the 1920s was its popularization of the idea of the ensemble; a [harmony] of color and style among a variety of accessories.”23 The addition of color in advertising during the 1920s allowed for a new way for advertisers to attract consumers. Using color in advertising was and new and efficient way to take practical goods and turning them into a fashionable item, which Marchand explains by stating, “against the grayish blandness of such a background, a colored product could immediately and ingeniously provide an eyecatching advertising advantage.”24 Marchand provides various advertisements from the 1920s that incorporate color into their product, from pens and jackets, to bathroom accessories.25 Color advertising was most productive with bathroom accessory advertisements, which inspired its use in other products that manufacturers had never bothered to apply color to before, such as bed sheets. One specific company, Pepperell Manufacturing Company introduced a new line of colored sheets and pillowcases by announcing that, Roland Marchand. Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity. (London: The Regents of the University of California, 1985), 132 24 Ibid. 122 25 Ibid. 121 - 125 23 Miller 15 “every woman’s sleeping-room should express her personality.”26 Color was no longer used to grab a reader’s attention, but was beginning to be used as a way to personalize products and provide a connection between the good being advertised and the consumer. While the ensemble is a marketing scheme of the 1920s, advertisers found it very useful in the 1950s. With the growing number of families living in suburban neighborhoods and the new techniques being employed by advertisers, the ensemble approach has a large presence in the 1950s. Thomas Hine also discusses Marchand’s concept of ensemble in Populuxe. The suburban house also brought new ways to use color in products; advertisers expanded the use of color to be incorporated in every room. Houses in suburban neighborhoods were so alike that “if your company moved you from Cherry Hill, New Jersey, to Anaheim, California, the vegetation would be different, but you could probably move into much the same house.”27 Advertisers took this uniformity and created a sense of competitiveness in their advertisements by depicting the subject with the new and latest styles. Using an array of never before seen colors, manufacturers incorporated fashion and style into their products, which was then promoted by the advertisers. Ibid. 127 Thomas Hine. Populuxe: The look and life of America in the '50s and '60s, from tailfins and TV dinners to Barbie dolls and fallout shelters. (Toronto, Canada: Random House, 1986), 22. 26 27 Miller 16 Continuing with the popularity of colored bathroom accessories, manufactures carried this concept over to other rooms in the suburban home. Consumers now had the ability match all of their kitchen appliances, bedroom furniture, living room furniture, and even the office equipment. This was an easy method of advertising to consumers, mostly women, because the idea comes from the fashion industry. Women have been victim to fashion for much of history, so applying trends and style to their appliances and furniture seemed second nature to them. In using the ensemble approach, advertisers portrayed women as having the ability to become stylish trendsetters in their own neighborhoods. Not only does the ensemble method appear in appliances, but in other goods like toilet paper. According to this ad from ScotTissue in Life magazine, consumers were now able to purchase toilet paper that would match the color scheme of your bathroom, at a higher price of course. Consumers who purchased a “mint green” bathtub, sink and toilet now had the option of purchasing toilet paper to match. Not only will this toilet paper “blend in gently with…your shower curtain with the gold stars, or Dad’s new blue plaid towels,” but also “ScotTissue in color is such a big money’s worth, and you’re not constantly putting in a new roll because this big color roll lasts and lasts…your best color value for the whole family.”28 Manufacturers and advertisers were getting smarter about their products; women had already been taught the concept of trends through fashion; to apply this knowledge to a disposable 28 See Fig. 3 Miller 17 item such as toilet paper is both ridiculous and clever at the same time. If these consumers took a minute to think about what they were purchasing for a higher price compared to the use value of the product then they would realize the absurdity of buying the more expensive colored toilet paper. However, toilet paper wasn’t the only good being sold in a variety of colors. Many products, from refrigerators to bathtubs were also offered in different colors so that customers could potentially match all of your appliances by brand and color. However, color choices changed every year, just like with fashion; if an appliances broke down, the consumer could not simply buy a replacement in the same color because the color was most likely not offered any more, making it impossible to find a balance between trends and technology. Thomas Hine discusses this idea in his book, Populuxe, stating that this approach came “from both automobiles and clothing fashions [which marketed] new colors and color combinations…[and] the major decorating magazines initiated annual features on “this year’s colors.”29 And just as fashion is divided into seasons, “the increased importance of colors meant everything changed more often.”30 Advertisers portrayed the good consumer of the 1950s as having the ability to keep up with the new seasons, colors, and styles. Good consumers updated their bathrooms, kitchens, and bedroom so that they could appear modern Thomas Hine. Populuxe: The look and life of America in the '50s and '60s, from tailfins and TV dinners to Barbie dolls and fallout shelters. (Toronto, Canada: Random House, 1986), 20 30 Ibid. 20 29 Miller 18 and stylish. Advertisers used new colors and styles as a way to teach women that they could apply their knowledge of fashion trendsetting to the home. Style and Trendsetting One method advertisers used during this time was to make their consumers feel like trendsetters when buying their goods, much like you would in fashion. When applied to fashion, planned obsolescence is a synonym for trends. Fashion designs and clothing go in and out of style in an effort to get consumers to continue to buy clothes instead of hanging onto the clothing from the previous season. Manufacturers and advertisers saw the fashion industry with their seasons and trends and found a way to market their products to their audience so that they would want to update their furniture or appliances with newer versions that came in different colors.31 The most convenient part of this scheme was that advertisers didn’t have to find clever ways to manipulate consumers; their main audience, women, were already used to this idea from the fashion industry. Marchand discusses this concept through colored plumbing fixtures in the bathroom, describing it as a “color crusade to emancipate the bathroom from prim utilitarianism.”32 He also gives to examples of ads that show the incorporation of color, “style elements in line, pattern and decoration,” in bathroom furnishings.33 One ad in particular incorporates fashion and furniture into one scene. The Montgomery Ward & Ibid. 22-23 Roland Marchand. Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity. (London: The Regents of the University of California, 1985), 124 33 Ibid. 125 31 32 Miller 19 Co. advertisement depicts a color-coordinated bathroom, described as the “lake forest” outfit, and “the lady of the house [being used like] a prop to contribute to the bathroom’s larger harmony of color and pattern.”34 Advertisers were trying to create a connection to fashion and appliances by incorporating both into the advertisements in an effort to reach out to female consumers. This tactic saw a lot of success in the 1920s and was incorporated into other products to “elevate consumption levels above those of mere utilitarian serviceability” and soon “invaded the kitchen, bedroom, and even the cellar.”35 Hine picks up on the trendsetting technique in advertisement in the 1950s. However, he makes the mistake of claiming that appliances were “manufactured in color for the first time, something that introduced a new fashion element” when Marchand has provided extensive evidence in the use of colored appliances in the 1920s.36 The use of this tactic, however, is accelerated in the 1950s because due to the popularity of the suburban neighborhood: “home builders phased out the basic house and started coming up with new and elaborate models which could be fitted and personalized with a series of options and upgrades…the arrival of new materials, particularly new kinds of floor and wall coverings, brought distinctly new looks…from both automobiles and Ibid. 125 Ibid. 126 36 Thomas Hine. Populuxe: The look and life of America in the '50s and '60s, from tailfins and TV dinners to Barbie dolls and fallout shelters. (Toronto, Canada: Random House, 1986), 21 34 35 Miller 20 clothing fashions came new colors and color combinations that rendered old rooms stodgy.”37 Marchand gives evidence of the use and popularity of colored appliances, but Hine gives evidence of the expanded use of color in other aspects of design in the house. In analyzing the collection of advertisements for this paper, I found that while color had been used in the past, Hine is correct in his argument that advertisers began to use this tactic outside of kitchen and bathroom appliances. In a Lincoln advertisement from Life in 1956, advertisers claimed that the first thing consumers’ notice was the trendsetting style of their products.38 In fact, the overall look and style of the vehicle is the first thing mentioned in the ad. The style that the Lincoln brand is the first thing observed before they even consider the “other qualities” the product offers.39 Many of the car advertisements during the 1950s mention very little about anything else the car might have to offer. It is all about style and how what you purchase makes you appear to others. In the Lincoln advertisement, an older couple watch as a younger couple leave in their car, not even paying attention to the older couple waving goodbye.40 Both couples appear to be part of a higher class, though the man and woman in the Lincoln seem to be socially and economically superior to the other pair. What Lincoln is trying to compel consumers Ibid. 20 See Fig 4 39 See Fig. 4 40 See Fig. 4 37 38 Miller 21 to feel when they see this ad is that buying a Lincoln will give you the appearance that you are from the upper class and have the money to purchase luxurious items, such as a car. In addition, the setting of the ad looks like it takes place in the South, which is a play on the nostalgia associated with pre-Civil War South. The appearance of consumers showing off their luxury goods does not just appear in car advertisements but appliance ads as well. The Gas Range advertisement from Good Housekeeping also boasts a modern style to its audience.41 The advertisers promote that this particular range, made in 1948, is more advanced then the one made in 1947 or any other competing model on the market. Not only that, but this brand was the first to bring its customers “smokeless broiling, heat-controlled ovens, simmer burners, [and] table-top designs!”42 This was not the only appliance company that pushed this agenda. Hotpoint Appliances also claimed to offer the latest technology for their customers. In fact, their dryer “outmodes all previous dryers” as well as asserting that it is the “first” and the “new[est]” in the field of technology. 43 This kind of marketing is targeted to their customers’ competitive natures; who wouldn’t want to be the first in the neighborhood to have the latest appliance technology has to offer? Especially when they could get it in the latest “in season” colors. Colors weren’t the only thing that went in and out of style. Every year car companies would find something different to add to their cars that the previous year See Fig. 5 See Fig. 5 43 See Fig. 6 41 42 Miller 22 did not have and base their marketing on those changes. The previous car is no longer acceptable in the eyes of advertisers and they wanted consumers to feel the same way. Cars were a good that you could show off not just in your driveway but also on the road and at the market; they are the quintessential example of a consumers buying power. Thomas Hine explains it well in his book, Populuxe: “In 1954, general Motors unveiled something called the Firebird, an experimental show car meant for display in the very popular “Motoramas” the company held periodically in various American cities. These were exercises in marketing, not technology, and the cars shown were often simply versions of current models with heightened symbolic content, or trials of features that were a year or two away…in 1955, however…the dull little car, which had been available in colors like dark blue, dark green and deep violet, all of which seemed only to be gradations of basic black, came forth in color combinations like coral and charcoal gray. And Chevrolet was not alone…all of Chrysler Corporation’s models… were restyled that year.”44 Both manufacturers and advertisers realized that their audience would fall for simple changes, like the color of the car, as an improvement and used that to market their cars. Good consumers should be willing to buy the new and latest model because they should want to be the first to have the new gadget to show off. Thomas Hine. Populuxe: The look and life of America in the '50s and '60s, from tailfins and TV dinners to Barbie dolls and fallout shelters. (Toronto, Canada: Random House, 1986), 90 44 Miller 23 Luxury and Leisure Marchand also mentions the concept of leisure and how it was applied to the home. The image of housework was transformed from a chore to something else; advertisers and manufacturers of home appliances “promised that their labor-saving products and services would bring women the most fulfilling reward – leisure time.”45 This was depicted in ads by showing the housewife enjoying her leisure by either minimizing the product or removing it all together.46 Marchand gives an example of this in The Laundry Machinery Company’s advertisement, titled “”Might-have-been hours”…how many of them are YOURS?”47 This ad depicts a woman with an iron staring at the clock that shows images of leisure activities she could be involved in if she weren’t still doing her chores.48 The emphasis is not placed on the product itself but of the benefit of leisure the product would bring to the consumer. Hine doesn’t discuss how advertisements depicted leisure or luxury but he does discuss a new form of it that incorporated leisure, consumerism, and social interaction. Tupperware parties were very popular in 1950s suburban neighborhoods. Women, in return for hosting a party, received free Tupperware products. These parties were Roland Marchand. Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity. (London: The Regents of the University of California, 1985), 171 46 Ibid. 171 47 Ibid. 173 48 Ibid. 173 45 Miller 24 successful as well; “nobody would leave without at least one piece of Tupperware.”49 There were many other ways to spend leisure time, such as watching TV shows like The Life of Riley, and I Love Lucy, which eventually moved the main characters from their Manhattan apartment to a suburban neighborhood in Connecticut. Food preparation also became easier, like TV dinners and Lipton’s onion dip mix.50 These easy to prepare foods were supposed to allow more leisure time for housewives. Leisure and luxury were not easy to advertise in the 1950s, however; they had two decades of financial insecurity to overcome. Luxury is yet another theme found in these 1950s advertisements in many ways; the luxury of technology, time, and money. The majority of Americans at this time were not used to luxury; the economy had become slow, due to the Great Depression. Advertisers were desperate to continue their success from the 1920s. They were focused on booting morale, inspiring consumers, and reassuring their audience that spending would, in fact, save the economy.51 Advertisers also had to combat the discouragement of luxury and leisure during the 1940s when all efforts were focused on the war. Luxury and leisure were still portrayed throughout these two decades but never to the extent that is seen in the 1950s. One interesting difference I’ve found in my advertisements is that, unlike Marchand’s ads from the 1920s that minimized or Thomas Hine. Populuxe: The look and life of America in the '50s and '60s, from tailfins and TV dinners to Barbie dolls and fallout shelters. (Toronto, Canada: Random House, 1986), 35 50 Ibid. 25-27 51 Roland Marchand. Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity. (London: The Regents of the University of California, 1985), Chapter 9 49 Miller 25 removed the product, the 1950s ads always depict the product and have either removed the person or minimized them. In just about every advertisement analyzed for this paper, luxury and leisure are present, if not the main aspect. In the Lincoln advertisement found in Life luxury is a main theme. Just looking at the extravagant vehicle taking up the majority of the illustration, one can almost feel the luxury exuding from it. If that isn’t enough, the audience can also take in the wealth and opulence from the rich clothing and jewelry the couple in the Lincoln is wearing, or the large Southern-style plantation in the background. The mansion itself brings the consumer back to the romanticized preCivil War era with large white columns and manicured landscaping. Not to mention the dominating presence of the affluent white upper class. In the description below the picture, the subtitle reads, “people who know fine cars are changing to Lincoln.” The use of the word “fine” also suggests the luxuriousness of the car. Luxury isn’t just implied through pictures, but through words as well. In an overwhelming amount of advertisements, particularly about home appliances, the words “quick,” “easy,” and “automatic” can be found. Purchasing a new automatic dryer, or the new advanced gas range, would not only hint to your economic ability to purchase such advanced technology, but allow you leisure time that was never available before. No more spending time hanging your clothes out on the line or worrying about rainy weather ruining your freshly cleaned linens. You could now through your clothes into the automatic dryer, press a few buttons, then walk away Miller 26 without a worry until the buzz indicated that your clothes are now dry. The General Electric washer will make your clothes sparkling clean “without a bit of effort.”52 These appliances became part of a family’s every day life. These goods weren’t just purchased for their ability to provide luxury and leisure; in the popular suburban neighborhoods, good consumers should want to show off their financial ability to purchase these household appliances and luxurious cars. Visual Clichés Another theme Marchand discusses in his book is that of the visual clichés. Marchand has referenced many advertisements that take the product and increase its size to the point where “huge refrigerators towered above tiny towns of consumers [or] immense cars straddled the rivers and towns of miniaturized countryside below. One example that sums up this “heroic proportions” technique is an ad that shows a gigantic air-conditioned refrigerator that is towering over a crowd of miniature people. This method was meant to point out “the “kolossal” image was not only “almost overpowering in its demand upon reader attention” but also commanded “confidence and respect”” as well as to allude to the objects dominance and transcendence.53 Hine fails to mention this advertising technique but I have found this theme in many of my advertisements, especially home appliance ads. One interesting difference I’ve found in my advertisements is that, unlike Marchand’s ads from the 1920s that See Fig. 2 Roland Marchand. Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity. (London: The Regents of the University of California, 1985), 266-267; *spelled “kolossal” 52 53 Miller 27 minimized or removed the product, the 1950s ads always depict the product and have either removed the person or minimized them. In the Hotpoint advertisement, the woman showing off their newest dryer has been reduced to a smaller size than that of the appliance. This also appears in the Gas Range ad, in which the woman is not even half the size of the range. It is almost as if the advertisers are belittling the importance of the women in the ads; they no longer play a huge role in cooking or doing the laundry because the appliance is advertised to do everything for them. The advertisements are trying to portray the fact that women, after purchasing that particular good, will not have to spend as much time on household chores and would have more time for their families and social lives. This belittlement of women played to the popular notion that a woman’s work in the home is not work at all. The wife gets to stay home and take care of the chores and children while the husband has to go off into the public sphere and “bring home the bacon” to provide for his family. Most of the women in advertisements like this appear happy that they no longer have to put as much effort into those household chores. In fact, the woman at the bottom of the Hotpoint ad looks blissful.54 Another common expression held by the women is a look of adoration and love, such as the woman in the other woman in the Hotpoint ad.55 According to these advertisements, a good consumer should feel love for the appliances, almost as if they were a member of the 54 55 See Fig. 6 See Fig. 2 and 6 Miller 28 family. Though these women may appear miniscule in comparison to the home appliances, their size speaks volumes. First Impressions Roland Marchand discusses the parable of the first impression in the 1920s and states that “first impressions brought immediate success or failure” to a person and a fear of offending or committing a faux pas became a realistic fear invented and maintained by advertisements. In the 1920s, ad men capitalized on the importance of the first impression by being very direct. Marchand cites many advertisements with very direct ways of promoting this parable, but one in particular explains it perfectly: “Suddenly, she sensed, as a knowledgeable mother would have been able to advise, that her chance of being invited to such an affair again – in fact, her whole future popularity – would be determined by this crucial first impression of her presence… her social destiny hung in the balance.”56 The woman and her husband in this advertisement worked tirelessly on the dinner menu and conversation topics that were appropriate for such an important party. However, her “dreary and out-of-date” furniture gave the “impression of dowdy tastelessness and lack of modernity ruined her plans for a flawless first impression.”57 Roland Marchand. Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity. (London: The Regents of the University of California, 1985), 208 57 Ibid. 56 Miller 29 This couple, because of this failed first impression among influential people, ruined their future and the husband remained in his sales job for the next twenty years. The parable of the first impression had already become ingrained in society by the 1950s. Thomas Hine argues that the design of suburban neighborhoods helped keep this parable alive; “the picture windows through which it was possible to view your neighbor’s furniture and family activities [and] the lack of effective fences” allowed the feeling of being watched by your neighbors. The pressure to “keep up with the Joneses” was amplified in the suburbs. Neighbors could peak inside your houses through these large “picture windows” and see your furniture and style but this wasn’t the only way for neighbors to judge you based off of your possessions. Tupperware parties became popular social interactions between suburban neighbors. In fact, one of the few things “nearly all suburbanites had in common was that they were consumers.” Tupperware parties were social gatherings a woman would host at her house and invite all her neighbors. Not only could she flaunt her ability to buy the Tupperware, but she could also show off her modern and stylish home. This parable of the first impression is also used in 1950s advertisements, though not presented so obviously as it was in the 1920s. This tactic was so ingrained in advertisements form the 1920s and on that it became unnecessary to be as visible in the 1950s. The theme of first impression can also be found in many of the advertisements I found on the 1950s. There tends to be a presence of an onlooker or neighbor that is admiring the subject’s new gadget. In the Caloric advertisement, the Miller 30 subject, a woman, is seen showing off her new “Ultramatic” Caloric gas stove to another woman.58 The owner of the stove is smiling wide at her neighbor who is looking on at the stove with a look of adoration. The subject of this advertisement is successful in making a good impression. She doesn’t own some outdated wood stove – she has a new Caloric gas stove! She is showing off her financial stability and her new stove that can end the “endless hours of range-tending” and gives her “more time to [her]self.”59 The Lincoln ad also offers a 1950s perspective on the parable of the first impression. As discussed earlier, there are two couples featured in this advertisement, the young couple in the Lincoln and the admiring older couple off to the side.60 No matter where you lived, in the city, the suburbs, or in a rural town, this car would be a perfect way to show off! In fact, this ad claims that people who know fine cars are purchasing Lincolns: so why not portray your self as one of these educated consumers that appreciate fine cars? In the 1950s, it became popular to trade in your car from the previous year and purchase the new model. Thomas Hine discusses this trend in detail in Populuxe. Harley Earl, a former Hollywood car customizer, worked for General Motors in the ‘50s to design new models.61 Earl’s designs were inspired by airplanes See Fig. 6 See Fig. 6 60 See Fig. 7 61 Thomas Hine. Populuxe: The look and life of America in the '50s and '60s, from tailfins and TV dinners to Barbie dolls and fallout shelters. (Toronto, Canada: Random House, 1986), 83 58 59 Miller 31 and other modern technology and created the popular tailfin.62 In suburban neighborhoods, houses were identical looking but the car sitting in your driveway could say a lot about your financial stability, as well as style. A good consumer should always be prepared to make a good first impression, and they can accomplish this by keeping up with the fashion trends and purchasing the latest technological invention. Conclusion In a time that was so new for the consumers, advertisers in the 1950s capitalized on the consumers’ uncertainty to force an agenda they had had since their rise in the 1920s. Their goal was to promote spending to new levels that had never been seen before. Consumer culture, up to that point had forced consumers to err on the side of caution; save, don’t spend. Fear of another depression, like that of the 1930s, was still very real and sincere. But with the rise of wages and the decrease unemployment, manufacturers realized there was a potential for higher consumer spending. So they took ideas from methods they had already been using and found new ways to seduce consumers into spending by presenting them with new feelings associated with purchasing goods. Thomas Hine argues in his book, Populuxe, that many of these concepts were a product of the post-World War II consumer culture. However, I have found that this argument is flawed; Roland Marchand’s book, Advertising the American Dream, shows evidence of these techniques were not new to the 1950s, in fact they were first being 62 Ibid. Miller 32 used in the 1920s. Methods such as the parable of the first impression, visual clichés, impressions of luxury and leisure, and ensemble were initially used in the 1920s. What separates 1950s advertising from 1920s advertising is the amplified production and supply of goods, increased wages, a decrease in unemployment, and the popularity of the suburban neighborhood. The combination of these created a consumer culture that had never before been experienced. Miller 33 Bibliography Dannoritzer, Cosima. The Light Bulb Conspiracy. Directed by Cosima Dannoritzer. Produced by Cosima Dannoritzer. Performed by Mke Anane and Michael Braugnart. 2010. Galbi, Douglas. Think! Communications Economics and Industry Analysis Blog. http://www.galbithink.org/ad-spending.htm. Hales, Peter. Levittown: Documents of an Ideal American Suburb. University of Illinois at Chicago. http://tigger.uic.edu/~pbhales/Levittown.html. Hine, Thomas. I Want That!: How We All Became Shoppers. New York, New York: HarperCollins, 2002. Hine, Thomas. Populuxe: The look and life of America in the '50s and '60s, from tailfins and TV dinners to Barbie dolls and fallout shelters. Toronto, Canada: Random House, 1986. Hobbs, Frank, and Nicole Stoops. Demographic Trends in the 20th Century. November 2002. http://www.census.gov/prod/2002/pubs/censr-4.pdf. Lears, Jackson. Fables of Abundance: A Cultural History of Advertising in America. New York, New York: The Perseus Books Group, 1994. Levittown Historical Society. A Brief History of Levittown, New York. http://www.levittownhistoricalsociety.org/history/htm. Marchand, Roland. Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity. London: The Regents of the University of California, 1985. Miller 34 May, Elaine Tyler. Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era. New York, New York: Basic Book Inc., 1954. Phrase Dictionary. Keep Up with the Joneses. http://www.phrases.org.uk/meanings/216400.html. Shmoop Editorial Team. Economy in the 1920s. http://www.shmoop.com/1920s/economy.html. United States Unemployment Rate. http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0104719.html.