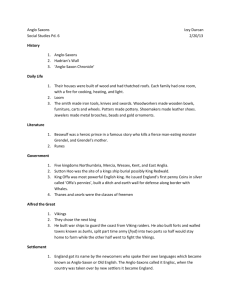

Anglo-Saxon Unit Readingspeters

advertisement

Anglo-Saxon Unit ~Readings~ Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 1 A Viking Mystery Beneath Oxford University, archaeologists have uncovered a medieval city that altered the course of English history By David Keys Smithsonian magazine, October 2010 Before construction could begin on new student housing at one of Oxford University’s 38 colleges, St. John’s, archaeologists were summoned to investigate the site in January 2008. After just a few hours of digging, one archaeologist discovered the remains of a 4,000-year-old religious complex—an earthwork enclosure, or henge, built by late Neolithic tribesmen, probably for a sun-worshiping cult. About 400 feet in diameter, the temple was one of the largest of Britain’s prehistoric henges, of which more than 100 have been found. Later, the archaeologists found pits full of broken pottery and food debris suggesting that people had used the henge as a medieval garbage dump millennia after it had been dug. Excited, they began searching for items that might reveal details of daily life in the Middle Ages. Instead they found bones. Human bones. “At first we thought it was just the remains of one individual,” says Sean Wallis of Thames Valley Archaeological Services, the company that did the excavating. “Then, to our surprise, we realized that corpses had been dumped one on top of another. Wherever we dug, there were more of them. Not only did we have a 4,000-year-old prehistoric temple, but now a mass grave as well.” After one month of digging at the grave site and two years of lab tests, the researchers concluded that between 34 and 38 individuals were buried in the grave, all of them victims of violence. Some 20 skeletons bore punctures in their vertebrae and pelvic bones, and 27 skulls were broken or cracked, indicating traumatic head injury. To judge from markings on the ribs, at least a dozen had been stabbed in the back. One individual had been decapitated; attempts were made on five others. Radiocarbon analysis of the bones convinced the archaeologists that the remains date from A.D. 960 to 1020—the period in which the Anglo-Saxon monarchy peaked in power. Originally from Germany, Anglo-Saxons had invaded England almost six centuries earlier, after the Roman Empire had fallen into disarray. They established their own kingdoms and converted to Christianity. After decades of conflict, England enjoyed a degree of stability in the tenth century under the rule of King Edgar the Peaceful. But “peaceful” is a relative term. Public executions were common. British archaeologists have discovered some 20 “execution cemeteries” across the country—testifying to a harsh penal code that claimed the lives of up to 3 percent of the male population. One such site in East Yorkshire contains the remains of six decapitated individuals. The Oxford grave, however, didn’t fit the profile of an execution cemetery, which typically contains remains of people put to death over many centuries—not all at once, as at Oxford. And execution victims tended to be various ages and body types. By contrast, the bodies buried at Oxford were those of vigorous males of fighting age, most between 16 and 35 years old. Most were unusually large; an examination of the muscle-attachment areas of their bones revealed extremely robust physiques. Some victims had suffered serious burns to their heads, backs, pelvic regions and arms. The most telling clue would emerge from a lab analysis, in which scientists measured atomic variations within the skeletal bone collagen. The tests indicated that the men ate, on average, more fish and shellfish than did AngloSaxons. Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 2 The mounting evidence increasingly pointed to an astonishing conclusion: this was a mass grave of Viking warriors. In the late eighth century a.d., the Vikings—a Scandinavian people from Denmark, Norway and Sweden—began a 300-year campaign of pillaging and piracy throughout Europe. Some scholars say that political changes (especially the emergence of fewer yet more powerful rulers) forced local Viking chieftains to seek new sources of revenue through foreign conquests. Others point to advances in shipbuilding that enabled longer voyages—allowing the Vikings to establish trade networks extending as far as the Mediterranean. But when an economic recession hit Europe in the ninth century, Scandinavian seamen increasingly turned from trading to pillaging. Most historians believe that England suffered more from the Vikings than other European countries. In the first recorded attack, in A.D. 793, Vikings raided an undefended monastic community at Lindisfarne in the northeast. Alcuin of York, an Anglo-Saxon scholar, recorded the onslaught: “We and our fathers have now lived in this fair land for nearly three hundred and fifty years, and never before has such a terror been seen in Britain as we have now suffered at the hands of a pagan people. Such a voyage was not thought possible. The church of St. Cuthbert is spattered with the blood of the priests of God.” The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a contemporary historical account, records that the Vikings waged some 50 battles and destroyed or ravaged scores of settlements. Dublin, one of the largest Viking cities in the British Isles, became a major European slave-trading center, where, historians estimate, tens of thousands of kidnapped Irishmen, Scotsmen, Anglo-Saxons and others were bought and sold. “In many respects the Vikings were the medieval equivalent of organized crime,” says Simon Keynes, a professor of Anglo-Saxon history at Cambridge University. “They engaged in extortion on a massive scale, using the threat of violence to extract vast quantities of silver from England and some other vulnerable western European states.” “Certainly the Vikings did all these things, but so did everyone else,” says Dagfinn Skre, a professor of archaeology at the University of Oslo. “Although admittedly, the Vikings did it on a grander scale.” Martin Carver, an emeritus professor of archaeology at the University of York, characterizes the antagonism between the Anglo-Saxons and the Scandinavians as part of a wider clash of ideologies. Between the sixth and ninth centuries, Vikings in Scandinavia preferred to be organized “in loose confederations, favoring enterprise,” says Carver. But other parts of Europe, such as Britain, yearned for a more orderly, centralized government—and looked to the Roman Empire as a model. Only one Anglo-Saxon kingdom—Wessex, ruled by Alfred the Great—is known to have withstood the Viking invasion. Alfred and his son, Edward, built up an army and navy and constructed a network of fortifications; then Edward and his successors wrested back control of those areas the Vikings had taken over, thus paving the way for English unification. After decades of peace, Vikings again raided England, in A.D. 980. At the time, the Anglo-Saxon ruler was King Aethelred the Unraed (literally “the ill-advised”). As his name suggests, popular history has portrayed him as a mediocre successor to Alfred the Great and Edgar the Peaceful. The 12th-century historian William of Malmesbury wrote that Aethelred “occupied rather than governed” the kingdom. “The career of his life was said to have been cruel in the beginning, wretched in the middle and disgraceful in the end.” To avert war, Aethelred paid the Vikings some 26,000 pounds in silver between A.D. 991 and 994. In the years that followed, the king employed many of them as mercenaries to discourage other Vikings from attacking England. But, in A.D. 997, some of the mercenaries turned on their royal employer and attacked the Anglo-Saxon southern counties. In early A.D. 1002, Aethelred again tried to buy off the Vikings—this time with 24,000 pounds in silver. Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 3 The geopolitical situation changed in England’s favor only when Aethelred made an alliance with Normandy and sealed the deal by marrying the Duke of Normandy’s sister in A.D. 1002. Possibly emboldened by the support of a powerful ally, Aethelred decided to take pre-emptive action before the Danes again broke the truce. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Aethelred was “informed” that Danish mercenaries intended to “beguile him out of his life.” (It is unknown whether an informer learned of an actual plot, or if Aethelred and his council fabricated the threat.) Aethelred then set in motion one of the most heinous acts of mass murder in English history, committed on St. Brice’s Day, November 13, 1002. As he himself recounted in a charter written two years later, “a decree was sent out by me, with the counsel of my leading men and magnates, to the effect that all the Danes who had sprung up in this island, sprouting like cockle [weeds] amongst the wheat, were to be destroyed by a most just extermination.” Prior to 2008, the only known inhabitants of the St. John’s College garden had been the songbirds and squirrels that darted across the neatly cropped lawn and hid in an ancient beech tree. Generations of dons and students had strolled across that greenery, unsuspecting of what lay beneath. The lab data indicating that the men buried there for 1,000 years had eaten lots of seafood, plus the burn markings and other evidence, convinced the archaeologists that the grave probably held victims of the St. Brice’s Day massacre. Aethelred himself recounted exactly how the residents of Oxford killed the Danes in a local church: “Striving to escape death, [the Danes] entered [a] sanctuary of Christ, having broken by force the doors and bolts, and resolved to make a refuge and defence for themselves therein against the people of the town and the suburbs; but when all the people in pursuit strove, forced by necessity, to drive them out, and could not, they set fire to the [building’s] timbers and burnt [it] down.” Wallis, the archaeologist in charge at Oxford, surmises that the townspeople loaded the corpses onto a cart and drove out through the north gate of the city, past land that today encompasses the Oxford colleges of Balliol and most of St. John’s, then threw the Vikings into the prehistoric henge—the largest ditch nearest the city’s northern exit. A year after this discovery, another team of investigators, from the company Oxford Archaeology, were looking for evidence of prehistoric activity at a site 90 miles to the southwest in the English county of Dorset, near Weymouth, when they discovered a second mass grave. This one held the skeletons of 54 well-built, fighting-age males, all of whom had been decapitated with sharp weapons, most likely swords. Lab tests of the teeth suggested the men were Scandinavians. The ratio between various types of oxygen atoms in the skeletons’ tooth enamel indicates the victims came from a cold region (one man from inside the Arctic Circle). Radiocarbon dating placed the victims’ deaths between A.D. 910 and 1030; historical records of Viking activities in England narrow that to between A.D. 980 and 1009. The corpses had been unceremoniously dumped in a chalk and flint quarry that had been dug hundreds of years earlier, possibly during Roman times. Although no historical account of the massacre exists, the archaeologists believe the Vikings were apprehended and brought to the site to be executed. The discovery of the two mass graves may resolve a question that has long vexed historians. In the centuries following the St. Brice’s Day massacre, many chroniclers believed that the Danish community in England (a substantial percentage of the population) was targeted for mass murder, akin to a pogrom. Certainly there was undisguised hatred for the Scandinavians, who were described by contemporary writers as “a most vile people,” “a filthy pestilence” and “the hated ones.” But more recently, the massacre has been seen more as a police action against only those who posed a military threat to the government. The discovery of the two mass graves supports this view, since victims were found where the rebellious mercenaries would have been stationed: close to royal administrative centers (usually towns or important royal estates) on or near England’s south coast and in the Thames Valley. By contrast, no such graves have been found in the region of eastern England once known as the Danelaw, which was populated by descendants of Scandinavian settlers. “I would estimate that out of a total population of around two million in England, perhaps half were of Scandinavian or partly Scandinavian origin—most of whom were loyal subjects,” says Ian Howard, a historian writing a biography of Aethelred. “I think it inherently unlikely that the king ever intended to kill them all, as it would obviously have been impossible to do so.” Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 4 Far from being just a ghoulish footnote to medieval history, Aethelred’s massacre of the Danes likely reinforced Danish determination to attack England and set in motion a chain of events that would change the course of England’s future. In A.D. 1003, the year after the massacres, King Svein of Denmark launched his own assault against a much wider swath of Anglo-Saxon England. This renewed aggression continued off and on for more than a decade, inspiring a level of terror the Anglo-Saxons had not faced since the first Viking invasions a century and a half earlier. An Anglo-Danish text, the Encomium Emmae Reginae, written around A.D. 1041 or 1042, described the Danish war fleet of 1016: “What adversary could gaze upon the lions, terrible in the glitter of their gold...all these on the ships, and not feel dread and fear in the face of a king with so great a fighting force?” Both circumstantial and historical evidence suggests that revenge was at least part of the motivation for Svein’s invasions. There were almost certainly blood ties between Aethelred’s victims and Danish nobility. According to medieval chronicler William of Malmesbury, Svein’s sister (or, possibly, half sister) Gunnhild was a victim of the St. Brice’s Day massacre (although her body has never been found). Neither her gender nor her royal blood saved her, probably because she was the wife of Pallig, one of the turncoat mercenaries. Wrote William of Malmesbury: “[She was] beheaded with the other Danes, though she declared plainly that the shedding of her blood would cost all England dear.” Gunnhild’s words proved prophetic. The Danes ultimately conquered England, in A.D. 1016, and Canute, the son of Svein, was crowned the nation’s king in London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral in January 1017. Twenty-five years later, the Anglo-Saxons would regain the crown, but only for a generation. The Scandinavians, who had refused to renounce the throne, embarked on yet another onslaught against England in September 1066—less than a fortnight before William the Conqueror, the Duke of Normandy, launched his own invasion of the country. Although the English pushed back the Scandinavian invaders, the effort so weakened the Anglo-Saxons that they were defeated by William at the Battle of Hastings, also in 1066. The Norman Conquest consolidated the unification of England, as the new rulers introduced a more centralized, hierarchal government. The Anglo-Saxons would rise again, their culture and language merging with that of their oppressors to produce a new nation—the predecessor of modern England, and eventually an empire that would span half the globe. A Viking Mystery Questions for Comprehension 1. Describe (using evidence) how the archaeologists knew that the bodies found in the grave were non-native. 2. How did the researchers know that the mass grave was not an execution cemetery? 3. According to the author, what is the modern day equivalent to the Vikings? 4. How did Aethelred deal with the threat on his life? 5. What was the significance and result of the Battle of Hastings? Historical Analysis Anglo-Saxon Notes (Separate, in class assignment. See me for scan copy if absent) Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 5 Norton Anthology “Introduction to Beowulf” (In class assignment) Read the entire excerpt, including the Atlas maps. Answer each thoroughly. Use complete sentences. 1. Name at least three tenets of the heroic ideal. 2. Name at least two OTHER epic poems that depended on the oral tradition. 3. Why was poetry so important to a non-Christian society? 4. Who was Bede, and why was he significant? 5. Who was Alfred? What did he rule? What was his legacy? 6. How was Christ made palatable to the heroic ideal? 7. What was the importance of women in Anglo-Saxon literature? How were they named? 8. What was the role of romantic love? 9. Define the use of ironic understatement. 10. How has the Germanic role of the heroic ideal translated into our current ideal of heroism? Apply at least three characteristics. Medieval Diseases and Cures ttp://www.medievalarchives.com/2013/09/10/mapmedieval-diseases-cures/ This podcast is available by link on the Peters website. Please listen for homework and answer completely: 1. What was THE DISEASE of the middle ages? 2. What was bloodletting, and what was it used to treat? 3. How did one treat nasal congestion? 4. What was the treatment for baldness? 5. Did illness almost certainly result in death? Why? Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 6 Decoding Anglo-Saxon art Rosie Weetch, curator and Craig Williams, illustrator, British Museum One of the most enjoyable things about working with the British Museum’s Anglo-Saxon collection is having the opportunity to study the intricate designs of the many brooches, buckles, and other pieces of decorative metalwork. This is because in Anglo-Saxon art there is always more than meets the eye. The objects invite careful contemplation, and you can find yourself spending hours puzzling over their designs, finding new beasts and images. The dense animal patterns that cover many AngloSaxon objects are not just pretty decoration; they have multi-layered symbolic meanings and tell stories. Anglo-Saxons, who had a love of riddles and puzzles of all kinds, would have been able to ‘read’ the stories embedded in the decoration. But for us it is trickier as we are not fluent in the language of Anglo-Saxon art. Anglo-Saxon art went through many changes between the 5th and 11th centuries, but puzzles and story-telling remained central. The early art style of the Anglo-Saxon period is known as Style I and was popular in the late 5th and 6th centuries. It is characterised by what seems to be a dizzying jumble of animal limbs and face masks, which has led some scholars to describe the style as an ‘animal salad’. Close scrutiny shows that Style I is not as abstract as first appears, and through carefully following the decoration in stages we can unpick the details and begin to get a sense for what the design might mean. Silver-gilt square-headed brooch from Grave 22, Chessell Down, Isle of Wight. Early Anglo-Saxon, early 6th century AD Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 7 Decoding the square-headed brooch. Click on the image for larger version. One of the most exquisite examples of Style I animal art is a silver-gilt square-headed brooch from a female grave on the Isle of Wight. Its surface is covered with at least 24 different beasts: a mix of birds’ heads, human masks, animals and hybrids. Some of them are quite clear, like the faces in the circular lobes projecting from the bottom of the brooch. Others are harder to spot, such as the faces in profile that only emerge when the brooch is turned upside-down. Some of the images can be read in multiple ways, and this ambiguity is central to Style I art. Turning the brooch upside-down reveals four heads in profile on the rectangular head of the brooch, highlighted in purple. Click on the image for larger version. Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 8 Once we have identified the creatures on the brooch, we can begin to decode its meaning. In the lozenge-shaped field at the foot of the brooch is a bearded face with a helmet underneath two birds that may represent the Germanic god Woden/Odin with his two companion ravens. The image of a god alongside other powerful animals may have offered symbolic protection to the wearer like a talisman or amulet. Decoding the great gold buckle from Sutton Hoo. Click on the image for larger version. Style I was superseded by Style II in the late 6th century. This later style has more fluid and graceful animals, but these still writhe and interlace together and require patient untangling. The great gold buckle from Sutton Hoo is decorated in this style. From the thicket of interlace that fills the buckle’s surface 13 different animals emerge. These animals are easier to spot: the ring-and-dot eyes, the birds’ hooked beaks, and the four-toed feet of the animals are good starting points. At the tip of the buckle, two animals grip a small dog-like creature in their jaws and on the circular plate, two snakes intertwine and bite their own bodies. Such designs reveal the importance of the natural world, and it is likely that different animals were thought to hold different properties and characteristics that could be transferred to the objects they decorated. The fearsome snakes, with their shape-shifting qualities, demand respect and confer authority, and were suitable symbols for a buckle that adorned a high-status man, or even an Anglo-Saxon king. Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 9 The five senses on the Fuller Brooch. Click on the image for a larger version Animal art continued to be popular on Anglo-Saxon metalwork throughout the later period, when it went through further transformations into the Mercian Style (defined by sinuous animal interlace) in the 8th century and then into the lively Trewhiddle Style in the 9th century. Trewhiddle-style animals feature in the roundels of the Fuller Brooch, but all other aspects of its decoration are unique within Anglo-Saxon art. Again, through a careful unpicking of its complex imagery we can understand its visual messages. At the centre is a man with staring eyes holding two plants. Around him are four other men striking poses: one, with his hands behind his back, sniffs a leaf; another rubs his two hands together; the third holds his hand up to his ear; and the final one has his whole hand inserted into his mouth. Together these strange poses form the earliest personification of the five senses: Sight, Smell, Touch, Hearing, and Taste. Surrounding these central motifs are roundels depicting animals, humans, and plants that perhaps represent God’s Creation. This iconography can best be understood in the context of the scholarly writings of King Alfred the Great (died AD 899), which emphasised sight and the ‘mind’s eye’ as the principal way in which wisdom was acquired along with the other senses. Given this connection, perhaps it was made at Alfred the Great’s court workshop and designed to be worn by one of his courtiers? Throughout the period, the Anglo-Saxons expressed a love of riddles and puzzles in their metalwork. Behind the non-reflective glass in the newly opened Sir Paul and Lady Ruddock Gallery of Sutton Hoo and Europe AD 300-1100, you can do like the Anglo-Saxons and get up close to these and many other objects to decode the messages yourself. Click on the thumbnails below to view in a full-screen slideshow Decoding the great square-headed brooch from Chessel Down, Isle of Wight Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 10 Turning the brooch upside-down reveals four heads in profile on the rectangular head of the brooch, highlighted in purple. Decoding the great gold buckle from Sutton Hoo, Suffolk The five senses on the Fuller Brooch. The Sir Paul and Lady Ruddock Gallery of Sutton Hoo and Europe AD 300–1100 recently opened after a major redisplay in Room 41. Admission is free. 1. Which piece represents the earliest personification of the five senses? 2. Name at least two types of metalwork that reside in the Sutton Hoo Collection. 3. What was the major focus (the purpose of the intertwined figures) of the metalwork (two are provided)? 4. Why did warriors wear emblems of certain animals? 5. What timeframe does “Style I” art come from? The Exeter Book The largest collection of Old English Poetry, The Exeter Book was copied c 975AD. This manuscript was given to Exeter Cathedral by Bishop Leofric (died 1072). It begins with some long religious poems: the Christ, in three parts; two poems on St. Guthelac; the fragmentary “Azarius”, and the allegorical Phoenix. Following these are a number of shorter religious elegies, usually named “The Wanderer”, “The Seafarer”, “The Wife’s Lament”, “The Husband’s Message”, and “The Ruin” are all found here. These are secular poems evoking a poignant sense of desolation and loneliness in their descriptions of the separations of loved ones, the sorrows of exile, or the terrors and attractions of the sea, although some of them also carry the weight of religious allegory. In addition, the Exeter Book also preserves 95 riddles, a few of which follow: ILLUSTRATE These riddles on the right side of the paper. 5 I’m by nature solitary, scarred by iron And wounded by sword, weary fo battle. I often see the face of war, and fight Hateful enemies; yet I hold no hope Of help being brought to me in battle Before I’m cut to pieces and perish. Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 11 At the city wall sharp-edged sword, Skillfully forged in the flames by smiths, Bite deeply into me. I must await A more fearsome encounter; it is not form e To find a physician on the battlefield, One of those men who heal wounds with herbs. My sword wounds gape wider and wider; Death blows are dealt me by day and by night. I am…..___________________________ 6 Christ, the true giver of victories, Created me for combat. When my lord Urges me to fight, I often scorch mortals; I approach the earth and without a touch, Afflict a whole host of people. At times I gladden the minds of men, Keeping my distance I console those Whom I fought before; they feel my kindness As they once felt my fire when, After such suffering, I soothe their lives. I am…..______________ 11 My garb is ashen and in my garments Bright jewels, garnet colored, gleam. I mislead muddlers, dispatch the thoughtless On fool’s errands, and thwart cautious men In their useful journeys. I can’t think Why, addled and led astray, robbed Of their senses, men praise my ways To everyone. Woe betide addicts When they bring the dearest of hoards on high Unless they’ve foregone their foolish habits. I am….._______________________ 20. I’m a strange creature, shaped for a scrap, Dear to my lord, finely decorated. My clothing is motley and bright metal threads Mount thea deadly jewel my master Gave me – the man who at times involves me In a fight. I carry treasure then, The handiwork of smiths, gold in the court, All the clear day. I often dispatch Well-armed warriors. A king enriches me With silver and precious stones, honors me in the hall; he doesn’t stint but sings my praises to the gathering – men swigging mead; at times he holds me in reserve, at times Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 12 sets me free, travel- weary, eager in the fray. Often I put friend at the throats of friends; I’m widely reviled, the most accursed of weapons. If a cruel warrior should assault me in battle, I cannot hope for a son to avenge me on my slayer; nor will the family from which I sprang be increased through the children of mine unless, lordless, I have to leave the guardian who once gave me rings. If I follow a warrior and fight on his behalf, As I have done before for my master’s satisfaction, I must forego, as fate wills, the chance To father children. I cannot lie With a woman, but the same man who once Bound me with a belt denies me now The rapture of play; I must enjoy The treasure of heroes single and celibate. Tricked out with metal threads, I often Irritate and frustrate some woman; she inults me, Smacks her hands and runs me down, Yells abuses. This is not my kind of contest… I am…_________________ 85 My home is not silent, but I am not Loud-mouthed. The Lord shaped Our course together; I am swifter than he, Sometimes stronger; he’s more strenuous. At times I rest; he must run onward. But I live in him all the days of my life; If we’re divided, I’m certain to die. I am…..___________________ and a _____________ 26 An enemy ended my life, took away My bodily strength; then he dipped me In water and drew me out again And put me in the sun where I soon shed All my hair. The knife’s sharp edge Bit into me once my blemishes had been scraped away; Fingers folded me and the bird’s feather Often moved across my brown surface, Sprinkling useful drops; it swallowed the wood-dye (part of the stream) and again travelled over me, Leaving black tracks. Then a man bound me, He stretched skin over me and adorned me With gold; thus I am enriched by the wondrous work Of smiths, wound about with shining metal. Now my clasp and my red dye And these glorious adornments bring fame far and wide To the Protector of Men, and not to the pains of hell. If the sons of men would make use of me They would be safer and more sure of victory, Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 13 Their hearts would be bolder, their mind more at ease, Their thoughts wiser; they would have more friends, Companions and kinsmen (true and honorable, Brave and kind) who would gladly increase Their honor and prosperity, and heap Benefits upon them, holding them fast In love’s embraces. Ask what I am called, Of such use to men. My name is famous, Sacred in itself I am….__________________ 32. This world is adorned in diverse ways, Decorated with rare ornaments. I saw a strange contraption, a fine traveler Grind against the grit and move, screaming. The strange creature couldn’t see; it had No shoulders, arms, or hands; this oddity Had to move on one foot, travel fast Over the salt-fields. It had many ribs, And a mouth in the middle, useful to men. It carries food in plenty, performs a service, Each year it yields men a gift used By rich and poor. Tell me if you can, Oh man of wise words, what this creature is. I am….___________________ 50 On earth there is a warrior of wonderious origin. He’s created, gleaming, by two dumb creatures For the benefit of men. Foe bears him against foe To inflict harm. A woman often fetters him, Strong as he is. If women and men Provide for him in the proper manner And often feed him, he’ll obey them And serve them well. Those who succor him Win themselves pleasure. But this warrior savages The man who lets him become proud. I am….________ 77 Sea suckled me, waved sounded over me, Rollers covered me as I rested on my bed. I have no feet and often open my mouth To the flood. Now some man will Consume me, who cares nothing for my clothing. With the point of his knife he will rip the skin Away from my side, and straight away eat me Uncooked as I am. I am…..______________________ Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 14 T H E S E A F A R E R ~translated by Burton Raffel Annotation: Religion/Christianity=orange Nature Elements=yellow Kennings=pink Isolation/loneliness=blue 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 This tale is true, and mine. It tells How the sea took me, swept me back And forth in sorrow and fear and pain, Showed me suffering in a hundred ships, In a thousand ports, and in me. It tells Of smashing surf when I sweated in the cold Of an anxious watch, perched in the bow As it dashed under cliffs. My feet were cast In icy bands, bound with frost, With frozen chains, and hardship groaned Around my heart. Hunger tore At my sea-weary soul. No man sheltered On the quiet fairness of earth can feel How wretched I was, drifting through winter On an ice-cold sea, whirled in sorrow, Alone in a world blown clear of love, Hung with icicles. The hailstorms flew. The only sound was the roaring sea, The freezing waves. The song of the swan Might serve for pleasure, the cry of the sea-fowl, The death-noise of birds instead of laughter, The mewing of gulls instead of mead. Storms beat on the rocky cliffs and were echoed By icy-feathered terns and the eagle’s screams; No kinsman could offer comfort there, To a soul left drowning in desolation. And who could believe, knowing but The passion of cities, swelled proud with wine And no taste of misfortune, how often, how wearily, I put myself back on the paths of the sea. Night would blacken; it would snow from the north; Frost bound the earth and hail would fall, The coldest seeds. And how my heart Would begin to beat, knowing once more The salt waves tossing and the towering sea! The time for journeys would come and my soul Called me eagerly out, sent me over The horizon, seeking foreigners’ homes. But there isn’t a man on earth so proud, So born to greatness, so bold with his youth, Grown so brave, or so graced by God, Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 15 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 That he feels no fear as the sails unfurl, Wondering what Fate has willed and will do. No harps ring in his heart, no rewards, No passion for women, no worldly pleasures, Nothing, only the ocean’s heave; But longing wraps itself around him. Orchards blossom, the towns bloom, Fields grow lovely as the world springs fresh, And all these admonish that willing mind Leaping to journeys, always set In thoughts traveling on a quickening tide. So summer’s sentinel, the cuckoo, sings In his murmuring voice, and our hearts mourn As he urges. Who could understand, In ignorant ease, what we others suffer As the paths of exile stretch endlessly on? And yet my heart wanders away, My soul roams with the sea, the whales’ Home, wandering to the widest corners Of the world, returning ravenous with desire, Flying solitary, screaming, exciting me To the open ocean, breaking oaths On the curve of a wave. Thus the joys of God Are fervent with life, where life itself Fades quickly into the earth. The wealth Of the world neither reaches to Heaven nor remains. No man has ever faced the dawn Certain which of Fate’s three threats Would fall: illness, or age, or an enemy’s Sword, snatching the life from his soul. The praise the living pour on the dead Flowers from reputation: plant An earthly life of profit reaped Even from hatred and rancor, of bravery Flung in the devil’s face, and death Can only bring you earthly praise And a song to celebrate a place With the angels, life eternally blessed In the hosts of Heaven. The days are gone When the kingdoms of earth flourished in glory; Now there are no rulers, no emperors, No givers of gold, as once there were, When wonderful things were worked among them And they lived in lordly magnificence. Those powers have vanished, those pleasures are dead. The weakest survives and the world continues, Kept spinning by toil. All glory is tarnished. The world’s honor ages and shrinks. Bent like the men who mould it. Their faces Blanch as time advances, their beards Wither and they mourn the memory of friends. The sons of princes, sown in the dust. The soul stripped of its flesh knows nothing Of sweetness or sour, feels no pain, Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 16 100 105 110 115 120 Bends neither its hand nor its brain. A brother Opens his palms and pours down gold On his kinsman’s grave, strewing his coffin With treasures intended for Heaven, but nothing Golden shakes the wrath of God For a soul overflowing with sin, and nothing Hidden on earth rises to Heaven. We all fear God. He turns the earth, He set it swinging firmly in space, Gave life to the world and light to the sky. Death leaps at the fools who forget their God. He who lives humbly has angels from Heaven To carry him courage and strength and belief. A man must conquer pride, not kill it, Be firm with his fellows, chaste for himself, Treat all the world as the world deserves, With love or with hate but never with harm, Though an enemy seek to scorch him in hell, Or set the flames of a funeral pyre Under his lord. Fate is stronger And God mightier than any man’s mind. Our thoughts should turn to where our home is, Consider the ways of coming there, Then strive for sure permission for us To rise to that eternal joy, That life born in the love of God And the hope of Heaven. Praise the Holy Grace of Him who honored us, Eternal, unchanging creator of earth. Amen. The Wanderer Often the lone-dweller waits for favor, mercy of the Measurer, though he unhappy across the seaways long time must stir with his hands the rime-cold sea, tread exile-tracks. Fate is established! So the earth-stepper spoke, mindful of hardships, of fierce slaughter, the fall of kin: Oft must I, alone, the hour before dawn lament my care. Among the living none now remains to whom I dare my inmost thought clearly reveal. I know it for truth: it is in a warrior noble strength to bind fast his spirit, Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings 5 10 Page 17 guard his wealth-chamber, think what he will. Weary mind never withstands fate, nor does troubled thought bring help. Therefore, glory-seekers oft bind fast in breast-chamber a dreary mind. So must I my heart-often wretched with cares, deprived of homeland, far from kin--fasten with fetters, since long ago earth covered my lord in darkness, and I, wretched, thence, mad and desolate as winter, over the wave's binding sought, hall-dreary, a giver of treasure, where far or near I might find one who in mead-hall might accept my affection, or on me, friendless, might wish consolation, offer me joy. He knows who tries it how cruel is sorrow, a bitter companion, to the one who has few concealers of secrets, beloved friends. The exile-track claims him, not twisted gold, his soul-chamber frozen, not fold's renown. He remembers hall-warriors and treasure-taking, how among youth his gold-friend received him at the feast. Joy has all perished! So he knows, who must of his lord-friend, of loved one, lore-sayings long time forgo. When sorrow and sleep at once together 40 a wretched lone-dweller often bind, it seems in his mind that he his man-lord clasps and kisses, and on knee lays hands and head, as when sometimes before in yore-days he received gifts from the gift-throne. When the friendless man awakens again, he sees before him fallow waves, sea-birds bathing, wings spreading, rime and snow falling mingled with hail. Then are the heart's wounds ever more heavy, sore after sweet--sorrow is renewed-when memory of kin turns through the mind; he greets with glee-staves, eagerly surveys companions of men. Again they swim away! Spirits of seafarers bring but seldom known speech and song. Care is renewed to the one who frequently sends over the wave's binding, weary, his thought. Therefore, I know not, throughout this world, why thought in my mind does not grow dark when the life of men I fully think through, how they suddenly abandoned the hall, 15 20 25 30 35 45 50 55 60 headstrong retainers. This Middle-Earth each of all days so fails and falls Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 18 that a man gains no wisdom before he is dealt his winters in the world. The wise man is patient, not too hot-hearted, nor too quick tongued, nor a warrior too weak, nor too foolhardy, neither frightened nor fain, nor yet too wealth-greedy, nor ever of boasts too eager, before he knows enough. A warrior should wait when he speaks a vow, until, bold in mind, he clearly knows whither mind's thought after will turn. A wise man perceives how ghastly it will be when all this world's weal desolate stands, as now here and there across this Middle-Earth blown on by wind walls stand covered with rime, the buildings storm-shaken. The wine-halls molder, the wielder lies down deprived of rejoicing, warband all fallen, proud by the wall. Some war took utterly, carried on forth-way; one a bird bore off over the high holm; one the hoar wolf dealt over to death, one a warrior, drear-faced, hid in an earth-cave. Thus the Shaper of men destroyed this earth-yard, until, lacking the cries, the revels of men, old giants' work stood worthless. When he with wise mind this wall-stone and this dark life deeply thinks through, the wise one in mind oft remembers afar many a carnage, and this word he speaks: Where is the horse? Where the young warrior? 65 70 75 80 85 90 Where now the gift-giver? Where are the feast-seats? Where all the hall-joys? Alas for the bright cup! Alas byrnied warrior! 95 Alas the lord's glory! How this time hastens, grows dark under night-helm, as it were not! Stands now behind the dear warband a wondrous high wall, varied with snake-shapes, warriors fortaken by might of the ash-spears, 100 corpse-hungry weapons--famous that fate-and this stone-cliff storms dash on; snowstorm, attacking, binds all the ground, tumult of winter, when the dark one comes, night-shadow blackens, sends from the north 105 rough hailstorm in anger toward men. All is the earth-realm laden with hardship, fate of creation turns world under heaven. Here goldhoard passes, here friendship passes, here mankind passes, here kinsman passes: 110 all does this earth-frame turn worthless! So said the one wise in mind, at secret conclaves sat him apart. Good, he who keeps faith, nor too quickly his grief from his breast makes known, except he, noble, knows how beforehand to do cure with courage. Well will it be 115 Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 19 to him who seeks favor, refuge and comfort, from the Father in heaven, where all fastness stands. Translation copyright © 1982, Jonathan A. Glenn Questions: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Compare and contrast Seafarer and Wanderer. Use a Venn Diagram. In what ways does the theme of exile show up in each poem? WHY How are these two poems elegiac? Name and illustrate three kennings from the poems (cite properly) Quote and define one “Ubi Sunt” moment. Anglo-Saxon Unit Readings Page 20